Cheyenne River Reservation, South Dakota

A Strong Strategy of Housing Development | Cheyenne River

In this interview, conducted on September 9, 2020, Sharon Vogel, executive director of the Cheyenne River Housing Authority (CRHA), discusses the need for investment in infrastructure to support development and explains how the recent water moratorium affected the growth of housing and economic development on the reservation.

Established in 1963, CHRA is the tribally designated housing entity for the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. It currently manages 735 rental units and 152 Mutual Help1The Mutual Help program allows Indian housing authorities (IHAs) to help low-income families purchase a home. Each family makes a monthly payment based on 15 to 30 percent of its adjusted income. Payments are credited to an equity account that is used to purchase the home. units, and continues to build on its successful record of developing affordable housing by designing and financing homeownership opportunities for eligible families. —Annie Coombs and Zoë Malliaros, The Lakota Nation and the Legacy of American Colonization editors

Listen to Sharon Vogel explain the effects of the flooding of Cheyenne Agency following the building of the Oahe Dam on the Missouri River.

This audio recording is excerpted from the conversation that has been transcribed and edited in the interview below.

Annie Coombs and Zoë Malliaros interviewed Sharon Vogel in 2020.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Annie Coombs and Zoë Malliaros (AC and ZM): Can you introduce yourself and let us know how long you’ve been working for the Cheyenne River Housing Authority?

Sharon Vogel (SV): I’ve been with the Housing Authority 18 years. I’ve really been blessed. I have been so fortunate to be placed in different positions that have really helped me understand the voices of the people that we were serving. Housing is no different. I think that you truly have to understand the needs, understand the people.

View a map noting the locations of communities and sites mentioned in this interview, along with a discussion of land ownership and governance helpful in understanding this conversation.

I think that for the majority of housing directors, the people they serve have to go through doors to get to the executive director. Here in South Dakota, you can’t hide behind a door. You can’t manage from behind a desk. You absolutely have to meet with the people. You have to hear and listen. You have to be out in the communities. You have to understand that perspective in order to be effective. You can be at a grocery store and somebody will come up to you and talk to you about their housing needs. And so when you live in a small area where people have access to not only program directors but also to tribal leaders, then it, to me, is really a true form of democracy. It holds you accountable. I think it just makes you a better person, because it keeps you humble and it keeps you real. And you understand the urgency of housing development. You understand the urgency of taking good care of the property that we do have. The value of the houses that we do rent can’t be understated. We have to take good care of them, and we have to get them turned around so that they’re always occupied, because the housing shortage is so great. So I wanted to lead with that.

AC and ZM: Can you share the history of the Housing Authority and funding for housing on the reservation?

SV: You know, we’ve come a long way. In those earlier years, we were grateful to get what was given. Everybody got the same template. You had the same policies for everybody. Everybody was treated the same regardless if you were a large tribe versus a small tribe or if you had a small population versus a large population. There were a lot of earlier advocates and leadership in Indian housing that started to turn things around so that HUD2HUD is the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the federal department responsible for providing funding to Indian Housing Authorities. Until 1996, this inadequate funding constituted the majority of all federal resources allocated to tribal housing. had to recognize that housing wasn’t the same for everyone—that the template wasn’t going to work anymore.

Thankfully, around the 1990s, NAHASDA3According to the HUD website, the Native American Housing Assistance and Self Determination Act of 1996 (NAHASDA) reorganized the system of housing assistance provided to Native Americans through the Department of Housing and Urban Development by eliminating several separate programs and replacing them with a block-grant program. The two programs authorized for Indian tribes under NAHASDA are the Indian Housing Block Grant (IHBG), which is a formula-based grant program, and Title VI Loan Guarantee, which provides financing guarantees to Indian tribes for private market loans to develop affordable housing. [The Native American Housing Assistance and Self Determination Act of 1996] brought that self-determination aspect into it. That was really the beginning of leveraging your NAHASDA dollars; that was when mortgage lending was introduced, new partnerships were created. Since then there are opportunities within Indian housing. But within the federal allocation there are still some big issues that haven’t been resolved.

One is, of course, that the allocation coming down has been stalemated since NAHASDA. Even though the housing need is documented, that there’s overcrowding, that the population is growing … the allocation isn’t growing. It’s been challenging to try to meet the needs and to not have the increases to properly meet them. But when you don’t have enough money, what do you do? You really have to go out and develop a strong strategy of housing development through new partnerships, or leveraging your dollars and learning the new game from other housing entities or funders. We’ve been able to do that, fortunately.

AC and ZM: Can you describe some of the new housing developments that have been made possible by this leveraging?

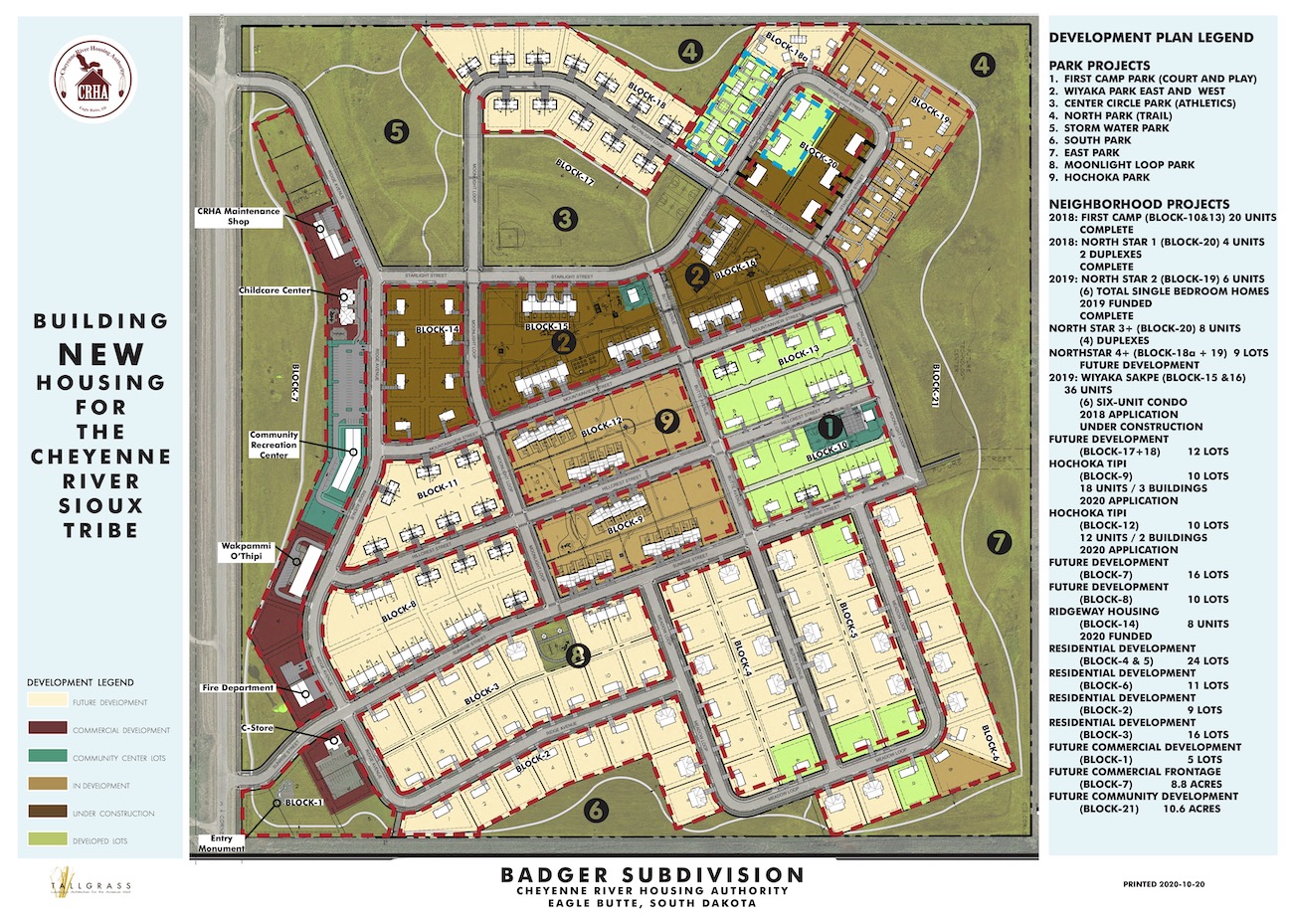

SV: Badger Park is really an interesting story for us, because not everyone has a Badger Park. The water moratorium put a halt to all housing development. You couldn’t build a new house and put it on the water system, because [that system] just couldn’t support any more users. What we did during that moratorium was to take our money that was allocated each year for housing development, and we put it into the infrastructure of a 160-acre site.

Download a PDF of the Badger Park plan.

And that paid off for us in a lot of ways. One, we knew that there was going to be a time when water would be available, and when that happened we needed to be ready with a fully developed site. It also paid off for us because we were able to leverage that fully developed site with new money that we found. If we didn’t have Badger Park, we would have had to find a piece of land and put money into the infrastructure before we could build the houses. But now that the infrastructure was put in, we focused on where to find money to build houses. It gave us an advantage in competitive applications, because we brought to the table infrastructure that was already in place, and we had more money to put towards building houses.

Our first project out at Badger Park was a 20-unit project, First Camp, and we were able to invest a million dollars into that and be matched with a million and more. Had we not used leveraging, it would take us forever to fill Badger Park. But with leveraging, we have financed 70 units to date for Badger Park and one other community. By leveraging, we can build more houses with less of our own money.

First Camp was followed by North Star One, which was four units: two duplexes for seniors and disabled.

And what’s unique about those two projects was that we were the first Indian entity that received housing trust funds. Each state gets housing trust funds, but not a lot of people go after that money because it is for very low-income rental only. But it ended up being a really great match for us. We also have North Star Two now, where we are building one-bedroom, stick-built houses.

Then, we just closed the deal on our first tax credit project out at Badger Park, and that’s for 36 units. That’s a 6.2 million dollar project, and our owner equity into it was $610,000.

We’re moving into the realm of really working on these diverse partnerships. Sometimes you’re managing multiple partners’ expectations, and that’s a new experience. It’s challenging, but it’s also doable.

We also knew that we had to look at housing throughout the reservation. We were funded for a project at the La Plant community, which we call Creekside Apartments, and that’s six units. It’s a $967,000 project. With housing trust funds funding $864,000 of that, our owner equity into that project is $102,000.

We’ve had good success with leveraging, and it’s competitive funding. You have to make sure that you’ve got a management portfolio that can stand on its own, and that an investor is comfortable with you. Having good, clean audits is important. So, it really requires us to take care of our existing stock and prove that we’re good property managers, that we are able to build good quality, energy-efficient projects.

The game has changed since the beginning of Housing Authority. We’re still facing a shortage: there’s good work to be done, but it’s hard work and it requires a lot of patience. When we identify a project, from the time we look at the concept of the whole design to where we have funding for it, it’s a two to-five-year process. But we are fortunate that we are learning, and building our reputation as a developer. Our success is the result of the hard work of many people and partners including the amazing team we have at CRHA, our tribal government leaders who support our housing development strategies, and our invaluable local, state, regional, and national partnerships. The diversity of our partners is remarkable; we have non-profit entities, government entities, and individuals, who are equally committed to affordable housing development. The reward of our success is of course the gratification of knowing that we are making a difference in the lives of the families we serve, one house at a time.

AC and ZM: How much housing is managed by the Housing Authority? What do you think the current need for housing is? How many people are on the waitlist?

SV: We manage 735 rental units and 135 Mutual Help units right now, and we have housing in almost every community.

I think the more important question is what percentage of the housing on Cheyenne River is subsidized. A large percentage of the housing on Cheyenne River is subsidized, and that’s just because of the poverty conditions. Families can’t afford market rent, and they are limited in housing choices.

Our waiting lists continue to be in the hundreds. We’ve developed a database that allows us to sort that housing and identify what the housing need really is. For a few years, we had a lot of people that were looking to downsize or were new couples. We’re trying to balance meeting the needs of the smaller families, the single households, while still trying to address the families that are growing and the families that have been waiting. The housing database has been very helpful to us.

Usually the first preference is Eagle Butte, and I always tell individuals, “I understand you want to live in Eagle Butte, but that’s where we’ve got hundreds of families on the waiting list. And if you looked at a smaller community, that waiting list may be less than 50, or in some places less than 25.” So we encourage people to pick a second choice.

But our rural communities have no infrastructure, and a person can’t get up, walk out their door, and walk to a job in that small community. There isn’t an infrastructure to support job growth in the smaller communities. The tribal government headquarters are here in Eagle Butte. It’s the major economy where the businesses are, where you’ve got Taco John’s and Subway and Dairy Queen. Those places hire. The community college is here, the hospital and the clinic. So the majority of the job opportunities are here in Eagle Butte. You’re naturally going to want to live in Eagle Butte, because you think that’s where the jobs are. And if you do get a job, you don’t have to commute. You don’t have to spend the money to maintain a car and have gas in there to go to work every day.

I think that there’s such a disconnect of understanding places of poverty. In an inner city, you have poverty that I think the majority of Americans recognize. Geographic-isolation poverty looks a lot different. You don’t have a public subway system. You don’t walk to a clinic. In geographic-isolation poverty, if you don’t have a vehicle, it’s very difficult. From a government perspective of coordinating services so that people aren’t completely disconnected, you have to make sure that you’ve got some mechanism to identify those families that need transportation to healthcare. The bus service is so important for education. We have a transit system and as far as I know, it does not serve every community, but it does have a daily schedule.

AC and ZM: What do you think the most pressing infrastructural need is on the reservation?

SV: We’re a large, land-based tribe. We’re very fortunate that we have access to land. If we identify tribal land, the tribe works with us to assign it. Then you have to make that a buildable site, which means you have to bring utilities in, so there’s the site development work to do, the grading, and to put the lines in. Everything now is going underground: the electrical, the water, and the sewer lines. Even your internet with the Telephone Authority now is put underground. So, all of those utilities have to go in before you can say that it’s available for a house to be put on there, and once you get it developed, you need streets so that people can drive safely, and ideally you’ve got sidewalks. There’s the safety issue of wanting to make sure there are street lights. You have to be able to finance all that infrastructure along with financing your actual building of the houses.

The other thing that’s important is that we have to balance rental and homeownership. We’ve got hardworking families that are ready for homeownership and can afford homeownership, provided we try to make it affordable for them. So when we put the infrastructure in, that’s one less thing to finance. We did that at Badger Park; we had 38 lots strictly for homeownership, with infrastructure already in. That’s one thing that we do to contribute to making homeownership an affordable product for some families.

The other is that we work with other resources to provide assistance with the down payment and closing costs. We’re really fortunate that the local native CDFI [community development financial institution], Four Bands Community Fund, has entered the mortgage lending space. We have Four Bands and another native CDFI on the Pine Ridge Reservation called Mazaska. What’s important is that Four Bands is a local lender, and we have had such great success that a million dollars was spent in the first two quarters that it became available through a USDA pilot program for 502 loans. That’s how we have eight units going up at Badger Park, I think six of them funded under the 502.4Section 502 Loans also known as Single Family Direct Housing Loans, are funded through the US Department of Agriculture Rural Development program. They provide low- and very-low-income families with loans for housing in rural areas.

The takeaway from this is the maturity that we have now being able to offer and develop multiple strategies to housing development. We’ll take people that can afford a mortgage payment out of our housing and put them into a homeownership path, and that opens up that rental for a family that’s been on the waiting list. It’s taken us a few years, but we’re moving that homeownership rate up. It’s important work and we couldn’t do it without the partners and the big game-changer of having a local lender that people are comfortable with, since they already have done work on asset building and the development of new native entrepreneurs.

Mortgages are not easily available, and especially not from a traditional bank. There are lending products out there geared for Native Americans. But the good thing about having multiple lenders and opportunities is that your higher-income families have choices, while there are also affordable mortgage products available for families with lower incomes.

AC and ZM: How has the water moratorium affected development?

SV: For Badger Park, it helped that the new hospital was built5In 2012, a water main and tower was put in for the new Eagle Butte Hospital, which made it possible to connect the future Badger Park development to the water system. IHS (Indian Health Services) has broader access to funding for infrastructure. because it required a new service line, and then we were able to tap into that line. One project can boost other projects. The water really became available three and a half years ago, so that’s when we started submitting applications. So I would say it was 2016, after the hospital was built, that we started to develop the line that we were going to tap into. Anything that we’ve got going in at Badger Park is the result of having water.

Out in the communities,6Rural communities located far from the main towns of Eagle Butte and Dupree. we had a few lots that were already hooked up to utilities, so we were able to build back on those vacant lots. The house may have burned down, or it had been demoed, so it was a valuable piece of real estate that wasn’t going to put a burden on the utilities because it had already been established.

AC and ZM: Is there anything that would help expedite the process for you, like resources or infrastructure that you wish you had?

SV: I think that reservation-wide, infrastructure would really help. Not everyone wants to live in Eagle Butte, and we need to balance the population.

The lesson learned is when you do a plot of land, it’s really wise to do mixed development on it. You can have rentals, but you also create that infrastructure for those future homeowners who can afford a new home, but can’t afford to buy the land and put the infrastructure in. And so it makes perfect sense to access infrastructure development–only dollars. Then you can come back and use that site to leverage and build your houses. It may not work for everybody, but it works for us.

To protect property values on the homeownership lots, we put covenants on the land, and then we also built the lots a little bigger than a typical rental. We knew that through the years people were going to be making improvements, and we wanted them to have a lot size that would allow them to do that. You just try to really think about what creates a good neighborhood, a safe neighborhood, so covenants would be things like setbacks to allow for sidewalks, or that you can’t have non-operating vehicles parked in the street.

The driving force was that we wanted families to be able to protect their investment. Like, you have to get approval for the type of fencing material you’re going to put up, because if you have small children and your neighbor puts up a barbed-wire fence, that’s a safety issue. So if you’re going to fence, you have to let us know what type of fence that you’re going to have. When you drive through that neighborhood, it’s a neighborhood that you want to live in.

Homeowners have a sublease with us, so we can enforce the covenants. They own the house but sublease the tribal trust land the property sits on. We do have a fee that we will use to make sure that the street lights are always going to be up there and to put sidewalks in when we are able to—those types of improvements. If we were to put a playground in a designated area, we would be able to contribute to some of that. I think it’s about $500 a year.

AC and ZM: Are there spaces that you would consider public spaces on Cheyenne River?

SV: I think about the cultural center as a public space, and the pow wow grounds during this COVID environment have become a public space, no longer just used for pow wows. A lot of our funerals are being held up there because it provides that open space and families can use social distancing. Before, it was always traditionally just used for pow wows. So that’s changed.

You know, I think we’re changing our mindset about public facilities and public space. That’s something that we’re incorporating out at Badger Park. We do have a community room that will be opening when we open up the First Camp housing project. And then with our tax credit project, we are getting another bigger space called a Community Center.

A lot of times, our housing developments were focused on building as many houses as possible. Out at Badger Park, we’re really changing that concept to where homes have garages, central air, a washer and dryer, a microwave. Those amenities were not traditionally available. But Badger Park has raised the bar for us, and I like that, because now that’s going to be the norm for us to provide those amenities, and families appreciate them. Originally we thought there’d be 200 families out there, but that was all single dwellings. Now we have multifamily units and we’re getting more out at Badger Park than we ever could have conceived. When you get the potential of having 500 individuals living at Badger Park, it creates its own little enterprise.

We’ve submitted a project to do lofts—working in partnership with Four Bands to create opportunities for entrepreneurs and businesses that will serve the community on the first floor, with lofts on top, and still try to serve families in affordable housing. But you also want to try to incorporate the cultural-positive elements of design and identity. We’re mindful of public spaces and that social interaction in those public spaces is going to be very important. So we have a community room and plan to reserve some of the green space for things like eating areas or picnic areas or looking at farmer’s markets and things like that. Badger Park has really allowed us those opportunities to think beyond just housing. There are other things you have to do to develop neighborhoods and develop safe communities. So that is in our future.

We really appreciate the fact that it’s important for our communities to be healthy communities, and to incorporate the cultural aspect into it, so that they can feel good about being Native: especially the children, that they have a positive self-identity as Lakota. But it takes money to do these things. And so I think that the funding sources need to make that allowance for places of poverty to really have those opportunities. Because usually it’s government taxes that pay for that public space. When you don’t have that source of revenue, it has to come from somewhere. To expect the local economy to create those spaces initially I think is very difficult. That’s why they’re lacking.

AC and ZM: Can you speak about the effects of the 1959 flooding of tribal land, including the Old Cheyenne Agency, along the Missouri River when the Oahe Dam was created?7The Pick Sloan Flood Control Act of 1944 authorized the US Army Corps of Engineers to build a series of hydroelectric dams along the Missouri River. In order to construct the Oahe Dam, the government seized over 104,000 acres of land along the eastern edge of Cheyenne River through eminent domain and flooded them, relocating 30 percent of the population from Cheyenne Agency to what is now Eagle Butte.

SV: I think that the dam really created poverty for those families, because they weren’t compensated to be able to replicate what they had at their homesite. Let’s say that you were self-sufficient, you had a home, you had a garden, you had livestock. Well, the money they were given as compensation was not sufficient to be able to replicate the livelihood that they had on that flooded piece of land. So they lost not only their property and their assets, they lost their livelihood, and then they had to fend for themselves. And I think that was something that was overlooked in talking about all of this. So in my opinion, it definitely contributed to the beginning of poverty. People were displaced and not compensated fairly to be able to continue their independence, their self-sufficiency and their livelihood

Then they started Eagle Butte, and it was not a traditional community. People were expected to just pick up and leave their traditional community. You’ve got to go up to Eagle Butte, there’s where the housing is. So the loss of their identity, that had its impact too, and then a cultural impact. I’m from this particular community, you know. So my feeling is that it was never in the favor of the tribal government or its memberships.

My mother owned a house that she purchased, and it got flooded. She worked for the BIA, and so the offices moved up here. I was in the first grade, so we started school down there, and then when the actual flooding was taking place, we were transferred up to this school here. My sister rode the bus from the old agency up here, because she was in junior high. She had to start school up here, whereas I got to wait a few months before they closed down our little elementary school. It was a relocation in every sense of the word.

When we moved up to Eagle Butte, the one thing that I thought a lot about is that there were no trees and it was just kind of up here in the middle of the prairie. Losing that beautiful landscaping that nature provided, you know, was just harsh. It was just such a loss. And it affected them, to lose that beauty that they grew up in, or that they lived in. I remember where our house was. It was one thing my mother loved: the big trees that were there, and the shade that they provided.

She worked for the BIA and moved into government quarters here, we lived in the old four-plex. To then be so close to your neighbors, it was just a shock. We were all supposed to shoosh: you know, “Don’t make so much noise.” All of a sudden, our lifestyle just changed. The rules changed and there were a lot of adjustments.

There were a lot of log cabins in each of the communities, you know. My grandmothers had one, and it was a one-bedroom little stick-built house. I spent my summers out along the Moreau River with my grandmothers, and when the day school was out we were packed up with all my other first cousins and sent down to what we called our home and spent our entire summer on horseback, just exploring the river and helping our grandmothers. Then when school started, we were all packed back up and brought back to school.

Biographies

is the executive director of the Cheyenne River Housing Authority (CRHA). She was born at the Old Cheyenne Agency; when this land was flooded, her family moved to Eagle Butte. She has worked for the past 18 years at the CRHA in housing management and development, and is an advocate for Indian housing issues on the state, regional, and national levels.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.