Cheyenne River Reservation, South Dakota

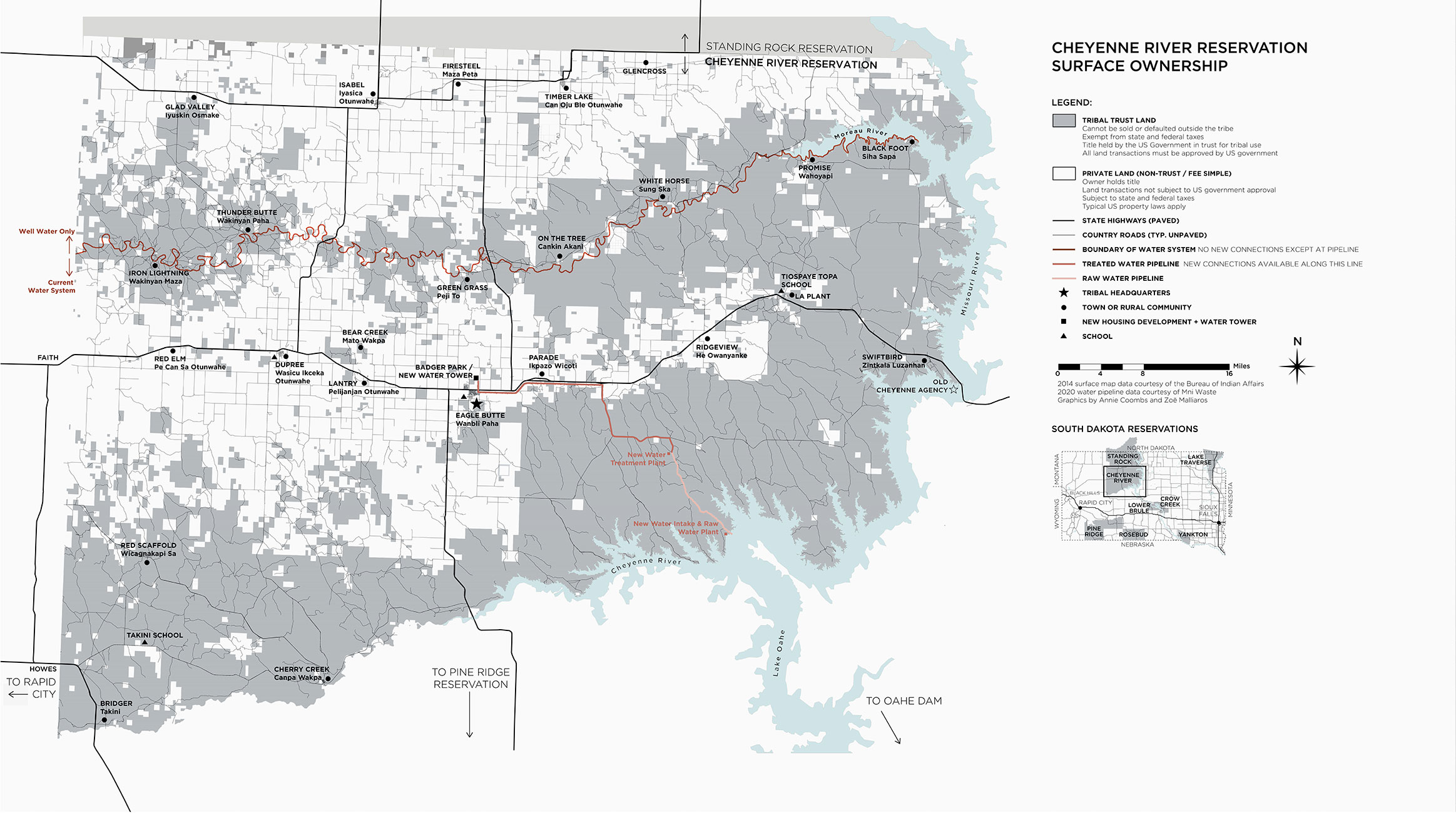

Cheyenne River Surface Ownership

To speak of community usually conjures up a mental image of a township with city blocks, border lines, and the buildings and residents therein. This would not be an accurate picture of the community as it is understood by the Lakota people. Community is much more encompassing than city limits and lines drawn on a map. Our way is much more comprehensive than that. It may be explained logically as the outlying areas, farms, and homesteads of rural dwellers and those who live outside the limits set by modern terminology. However, in our way of thinking it is the people and the total environment, regardless of the proximity or distance from the city center.1Text from the Tribe’s archived website, originally retrieved c. 2020. Visit the newly launched Cheyenne River Sioux Tribal website

(click here).

—Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe website

This surface ownership map shows that over 50 percent of the land within the boundary of the Cheyenne River Reservation is not held in trust for the tribe, but is instead controlled by private (typically non-Indian) owners. This checkerboard of tribal ownership is primarily a legacy of the 1887 Dawes Act,2Indian Land Tenure Foundation, “Land Tenure History,” accessed March 8, 2021. in which the US government allotted 160 acres of communal tribal land to individual tribal members, and then sold the “excess” to homesteaders for private ownership. Furthermore, the act specified that the trust land allotted to tribal members, if maintained, would automatically turn into “fee patent” holdings—private land, subject to property tax—after 25 years. For many reasons, such as foreclosure due to the inability to pay these new property taxes or the sale of land to white settlers due to financial hardship, this policy of “forced deeds” led to widespread loss of much of the original property on the reservations to non-Indians throughout the United States. In 1887 tribes throughout the country had 150 million acres of land; by 1934, the year the Dawes Act was repealed,3In 1934, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act, which prohibited “forced” deeds. Since this date, one must request to convert property to deeded land; otherwise it remains in trust. they had 50 million acres.4Stephen Pevar, The Rights of Indians and Tribes (New York: New York University Press, 2004), 9.

The outline of the Cheyenne River Reservation from the 1889 act of Congress that created the Lakota Reservations was 2.8 million acres; by 1976, 1.4 million of that remained in trust for the tribe or individual tribal members.5R.F. Bretz et al., “Status of Mineral Resource Information for the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation, South Dakota,” BIA Administrative Report 23 (1976), Table 1, accessed March 8, 2021. This erosion of the tribe’s control over its land has greatly hindered its ability to create sustainable economic activity and access resources necessary for survival and growth. Today, the majority of land along the central highway—the land most suited for commerce and most fertile for agriculture and ranching6A historic brochure published around the turn of the century to entice homesteaders to Cheyenne River describes Fox Ridge, along which highway 212 now runs, as a “tract of rich agricultural land” that had been the choice of homesteaders flooding the area, due to its quality, fertile loam soil, and proximity to transportation and the homesteader amenities that were being developed in Dupree. See: Ziebach County Historical Society, South Dakota’s Ziebach County, History of the Prairie (Dupree, S.D.: Ziebach County Historical Society, 1982), 20-41, accessed March 8, 2021.—is not in trust to the tribe. Below are brief descriptions of land, boundary, and agency definitions that may be helpful while reading the interviews.

Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)

The BIA is the federal agency responsible for administering and managing the 55,700,000 acres of land held in trust by the United States for Native American tribes. It was originally created under the Department of War and was responsible for administering treaties with sovereign tribes. In 1849, the agency was transferred to the Department of the Interior and became responsible for administering tribal law, indicating a shift in how the government saw its relationship with tribal governments.

Trust

Trust land refers to land whose title is “held in trust” to the tribe or individual tribal members by the federal government. This land can be sold or transferred only to members of the tribe. The benefits of trust land are that no property taxes are paid on it, and it can be passed down within a family.

Land passed down through family can go only to tribal members. In cases where it is not passed on, it returns to the tribe.

Some tracts of land are held by individual owners, but most land is considered to be “undivided interest land,” meaning that it is in trust to several family members. In this case, each family member owns a share of the whole property, not a unique piece of the land. The BIA has the power to approve or reject transactions.

Non-trust (also known as fee patent or deeded)

The reservation borders include a sizable amount of land that is not in trust and is governed by very different regulations. This land, called “fee patent” or “deeded” land, can be owned in full by anyone, Indian or non-Indian, and is subject to county, state, and federal property tax. It can be sold or leased at will.

It was only recently that the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe gained majority control (51 percent) of the land within the reservation, after the purchase of 24,000 acres of deeded land. It is still considered deeded until the debt is paid off, and can then be converted to trust land. Before this transaction, the tribe didn’t hold the majority interest on its own reservation.

Indian Country

Indian Country is considered to be trust and non-trust land that is within the boundaries of the reservation, as well as any territory outside the reservation that is under the jurisdiction of the tribe. Private property on fee patent land in Indian Country is subject to US and county taxes. However, these properties are under mixed jurisdiction between the tribe and federal government.

For example, if a non-major crime is committed between tribal members in Indian Country, the tribe has jurisdiction. However, if a tribal member commits a crime against a non-tribal member or vice versa, it is considered a federal crime, and the FBI has jurisdiction—not the state. All major crimes on the reservation are under FBI jurisdiction.

Conversion Programs

Individuals who own trust land can apply to have their land converted to fee patent land, a practice that is usually only done if a tribal member wants to sell their land to a non-Indian, as it subjects the land to taxation. In this case, the land is no longer in trust for the tribe.

Another process is the fee-to-trust program, in which a tribal member can apply to have their fee patent land converted to trust land. This process can only be started if all buildings on the property are paid in full.

City/Town Incorporations

Four towns within the reservation, Dupree, Eagle Butte, Isabel, and Timber Lake, have large sections that are incorporated by the state. Being incorporated by the state means that the land is deeded and is typically not owned by the tribe. In addition, incorporated towns have mayors and other state governance typical of a town off a reservation. For example, there are two Eagle Buttes: North Eagle Butte, which sits on trust land, and the City of Eagle Butte, which is located on fee patent land.

Surface/Minerals

Surface and mineral rights are independently controlled and can have different trust statuses. For example, in the case that surface trust land was allotted to an individual, the minerals below could be fee patent land owned by another individual. Legally, mineral rights trump surface rights, so if the owner of the mineral rights wants to access their minerals, she can penetrate the surface land. Because of this, the tribe’s current policy is to always keep mineral rights in trust when selling any fee patent land.

Biographies

and Zoë Malliaros are New York City–based architects. They have been traveling to the Cheyenne River Reservation for over 20 years, first as volunteers with the Sioux YMCA, and later for personal, academic and professional visits. In 2010, they were recipients of a fellowship from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (GSAPP) which resulted in Post-Reservation, a project that visualized housing, infrastructure, and the economy on the Lakota Sioux reservations. They both currently serve on the board of trustees for the Sioux YMCA.

Separate from their collaborations, Annie Coombs runs Siris Coombs Architecture, a practice that includes residential, cultural, and social impact projects. From 2016 to 2019, she served on the board of directors for Simply Smiles, a non-profit organization that provides housing and youth programs on Cheyenne River. Coombs has a master’s of architecture from Columbia University’s GSAPP and a bachelor’s degree in women’s studies from Wesleyan University.

Zoë Malliaros has worked professionally in both residential architectural design and nonprofit consulting as an owner’s representative for New York City nonprofit youth-focused organizations. She is a longtime member of the advisory council of ArtBridge, a NYC based nonprofit that empowers emerging artists to transform urban spaces. Malliaros has a master’s of architecture from Columbia University’s GSAPP and a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Harvard University.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.