Cheyenne River Reservation, South Dakota

Activism through Education and Nutrition

In this interview, conducted on November 6, 2020, Marcella Gilbert, a community organizer with a focus on food sovereignty and cultural revitalization, speaks about her experience of activism through education and nutrition. Her goal is to reintroduce sustainable traditional foods and organic farming to the reservation as an expression of fundamental survival and empowerment. —Annie Coombs and Zoë Malliaros, The Lakota Nation and the Legacy of American Colonization editors

Listen to Marcella Gilbert discuss identity and pride among young people today.

This audio recording is excerpted from the conversation that has been transcribed and edited in the interview below.

Annie Coombs and Zoë Malliaros interviewed Marcella Gilbert in 2020.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Annie Coombs and Zoë Malliaros (AC and ZM): Can you tell us about your life growing up?

Marcella Gilbert (MG): I was born on my reservation [Cheyenne River] and grew up with my grandmothers and great-grandparents. When I was six years old, I went to a day school. After that, I spent first through fourth grade at boarding school. Then my mom got me and we went to Cleveland and San Francisco.

Back during that time was the Indian Relocation Act1The Indian Relocation Act 1954 was a federal program that provided one-way transportation and a small stipend in order to encourage Native Americans to move from reservations to cities. It was in effect until 1972., a federal policy for getting Indian people off the reservation and into the mainstream to have access to jobs: “You can learn how to live among the white people and become one of us.” A lot of Indians went for it, including my mom and her sisters and brothers.

View a map noting the locations of communities and sites mentioned in this interview, along with a discussion of land ownership and governance helpful in understanding this conversation.

By the time I was 14, my mom had started the survival school in Rapid City. I spent from 14 to 18 there. Then I went to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and got my degree in community health education. I moved home and started working for the local tribal college. Ultimately, I ended up doing my master’s on fruit and vegetable consumption and how it affects bone density. After, I came back home, and have been living here since.

AC and ZM: Could you tell us a little bit more about the school that you went to that your mother started?

MG: In the ’70s everybody that was involved in the Wounded Knee occupation in 19732“The Wounded Knee incident occurred in 1973 when about 200 Oglala Lakota and followers of the American Indian Movement (AIM) seized and occupied the town of Wounded Knee for 71 days. In retaliation, various law enforcement surrounded the area and killed several Native representatives, who were unarmed.” See source. was going to jail. If you were an Indian man who had long hair, they automatically assumed you were American Indian Movement [AIM]3Started over 50 years ago, the American Indian Movement “was founded to turn the attention of Indian people toward a renewal of spirituality which would impart the strength of resolve needed to reverse the ruinous policies of the United States, Canada, and other colonialist governments of Central and South America. At the heart of AIM is deep spirituality and a belief in the connectedness of all Indian people.” See source.; today they call it profiling. They were arresting all the leadership of the movement and anybody that was related to them.

My mom was part of a group of people who rented a house that became the AIM House, where you could go to get resources. Kids would come and hang out at the AIM House because their parents were in jail.

In 1974, I was living with my aunt and going to school on the Rosebud Reservation. I begged my mother to let me live with her, and that’s how I joined the survival school, called the Cultural Learning Center. When I got there, they were learning all about treaties. I remember they handed me the 1868 treaty and said, “You need to read this and learn it”4The land base for the Great Sioux Nation was delineated by the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. Six years later, this treaty was broken when white settlers discovered gold in the Black Hills. The tribes fought with the US government over the Black Hills and surrounding area until 1889, when the Great Sioux Reservation was reduced and divided into seven distinctly separate reservations, known today as Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Standing Rock, Crow Creek, Yankton, Santee, and Lower Brule. See source.. The schooling was based on the issues of the day; we were exposed to everything that was going on within the American Indian Movement. Learning the treaties was very important, like Winters Doctrine5See source. and how that related to our water rights.

There were other survival schools that were starting all over Indian Country. There were two in Minneapolis. I think they’re still there: Heart of the Earth and The Red School House6See source..

We started in Rapid City, South Dakota, and we moved to Pine Ridge Reservation, to the community of Porcupine. My aunt got on the Rapid City school board and advocated for us to get school lunches and two teachers: a math and a reading teacher. Before that, at the AIM House, my mom was very busy. Sometimes there’d be like 30 of us young people there hanging out. The school system in Rapid City was very racist, so the kids who would go to school there were treated badly. They heard about our school and a lot of them would just show up. There was nowhere for Indian kids, and there still isn’t. As an adult, I asked my mom, how did you do it? She said, “Nobody cared, nobody came and knocked on my door and said, ‘Hey, what are you doing with all these kids?’” That alone told me a lot. We were pretty much invisible.

Our school moved to Porcupine on the Pine Ridge Rez and became the We Will Remember Survival Group. We wanted to honor the American Indian Movement by honoring the ones who were at Wounded Knee and who died there, not only in 1890 but also in 1973. We changed it from school to group because the way we were learning and functioning, it wasn’t the same as a school. We didn’t have a classroom. We didn’t have teachers. Our teachers were each other: the older ones would teach the younger ones. We would all sit around and read to each other. During this time, we were learning about other civil rights movements, like the Black Panthers and the Brown Berets.

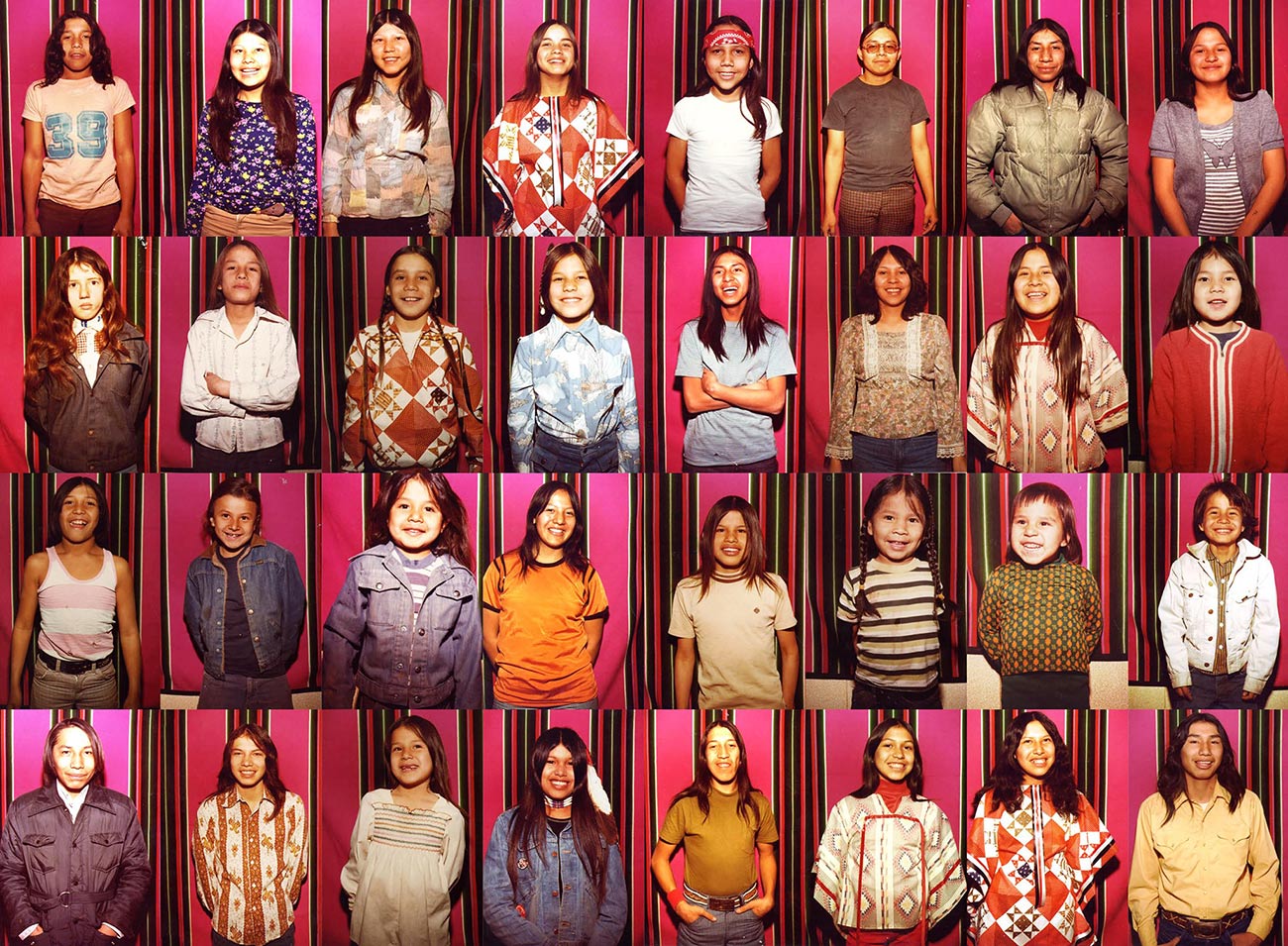

We Will Remember Survival Group, started by Madonna Thunder Hawk, class photos from the mid-1970s. Photo courtesy of the We Will Remember Survival Group

Then the International Indian Treaty Council was formed and they started having treaty conferences. Our school would travel to those and learn about our relationship on the international level; we learned about who else has treaties and how they are being violated. How do we come together as Indian people nationwide, globally, to protect these treaties that are the supreme law of the land? What are the strategies to get them enforced?

One year we traveled from Rapid City to Washington, where the Pit River Indians were fighting for their fishing rights. Because there was a rejuvenation of spiritual practice, we got to go to ceremonies all the way through Montana and into Oregon and Washington. Then we went down the coast because my mom was like, “This might be the only time that any of these kids see the ocean, because they may never leave the reservation or Rapid City.” We stopped in California and visited the Hupa people. After that trip we had a student exchange for a few years; some of us would go to Hupa and live with them and learn about their foods, then some of their young people would come to Pine Ridge. We ended up going all the way down the coast, through the Grand Canyon, and ended up in Farmington, New Mexico, for a treaty conference. That’s an example of what it was like to be in our survival group, hands-on learning from each other and getting a worldview of what it means to be an Indian person during that time.

I’m so glad I was able to be a part of that, because it’ll never happen again. I’m trying to recreate it, but it’s a different time and mentality today of young people. For instance, I worked with Simply Smiles, which is a nonprofit out of Connecticut that provides summer activities for our youth. After Standing Rock, they gave me an opportunity to do a week with young people to recreate a survival school learning environment. We took kids from the La Plant community, and we lasted three days. The young people that came there ranged between ages 13 and 19. They weren’t prepared to learn; they had too much trauma. They weren’t used to being responsible for their own education. They didn’t realize that it was education.

It was definitely a learning experience. We need to take kids who are ready and want to learn about who they are as an Indian person living in this country now. If we take kids off the street, there’s too much trauma. None of them knew how to read, which caused anxiety. Being in the Black Hills, we were going to learn about our sacred sites. We went from that to counseling. We had one 13 year-old young woman who was crying. Within the first few minutes of talking to her, she brought up several major issues related to trauma: suicide, sexual identity, her mom was in and out of their lives, and her grandma was sick and she was afraid she was gonna die. I realized if we’re going to do this, these kids need to be counseled on a regular basis. Maybe we need to focus on young people who are already functional and ready to learn, and are willing to take on learning in a good way.

It’s interesting, the American Indian Movement gave our people identity, but now we have a generation of young people who don’t know or care. It’s a clear indication of how the colonization of our people has manipulated our thinking. There’s so much loss. The American Indian Movement provided our people with pride and showed our people how to be intelligent. It showed our people what our true relationship is with the government and the United Nations. But some people can’t get beyond the trauma of boarding school. All those abuses and traumatic experiences that we learned in boarding school are being passed down to our kids. If you attended boarding school, you don’t know how to parent. If you’re not taking the time to learn how to parent, your kids aren’t going to know how to parent their kids, it just keeps getting passed down.

One of the things that saved my life is counseling. If you don’t know how to let that trauma go, and if you don’t understand it, you live in guilt, shame, and fear. How do you learn if you have to navigate all that crap? We’re trying to figure out how to do the survival school in a way that’s going to affect young people now. We’re still working on trying to figure out how to provide a space for young people to become strong Lakota people as adults. We’ve got to ensure our future somehow.

AC and ZM: How do you see the relationship between this history of trauma and health?

MG: It includes our health, because when you look at the history, it’s not just boarding schools. There were continued extermination policies of Indian people: before boarding schools there were military schools, and before military schools there were concentration camps7This is a reference to the US Government’s prolonged removal and relocation policies which resulted in genocide.. Our diets changed after the extermination of the buffalo. Because of fur trading and trapping, there was a mass murder of the natural world, which was our food supply. When we were free and we followed the buffalo, the buffalo went from up into Canada all the way into Northern Mexico. If we were following them, that’s a large area, and there’s a large variety of foods in there.

In the camps our diets changed overnight, because we weren’t allowed to have weapons. Men used their bows and knives and spears not just as weapons; they used them for everything. Every woman in our communities, including little girls, had a knife, because that’s what we needed if we were gathering food or if we were digging roots. If we were butchering an animal or tanning a hide or making a dress or whatever we were doing, we needed a knife. So you can imagine how much of our daily lifestyle was affected just from taking our knives. Not being able to have access to our foods and then forced to eat foreign foods. Wheat is not a native food to this country.

What sparked my interest was, why are Indian people getting diabetes at such young ages? When I was little, it was elderly people who were diabetic. Then in my 30s, people my age were getting it.

What I learned by doing my own research is that because we didn’t have wheat in our diet for thousands of years; our bodies are allergic to it. When we eat wheat, we don’t do well. That’s related to alcohol, too. Our people don’t have the enzymes in our body to break down sugars from wheat, rye, and barley, so we have allergic reactions. I started tying all that together and then looking at our original diets. I learned about the thrifty gene theory8With the thrifty gene hypothesis of 1962, James Neel put forth that those predisposed to diabetes differ metabolically and genetically from those who are not predisposed from birth onwards. He believed that “thrifty genes” were historically helpful, but have become harmful with modern diet and lifestyle, promoting the storage of fat for a famine that never comes. For further discussion, see Speakman, J. Thrifty genes for obesity, an attractive but flawed idea, and an alternative perspective: the ‘drifty gene’ hypothesis. Int J Obes 32, 1611–1617 (2008). See source.: that was really big back in the ’90s, and it just dropped off. There were some people within the academic community who were trying to discredit that theory, but they didn’t replace it with anything. I can’t find anything that can explain why our people have such high levels of diabetes and why our bodies react to the current foods that we’re eating in the way that they react.

That’s why I did research on our food. I started looking at our traditional diet, and it was protein based. Not only did our people eat a lot of meat, but we ate a lot of fruits and vegetables that had high protein content. Our diet had very little fat, and our carbohydrates were moderate. Then we were forced to eat foreign foods, which included white sugar, white flour, rice, lard, coffee, beans—those kinds of things.

It was really hard to find any kind of documentation of the history of our people’s eating habits, other than buffalo and deer. One of the things that I learned is that our people believed in eating clean foods, which meant you didn’t eat animals or fish that were dirty, like cows and pigs. I learned that our people were so connected to our belief systems that many of them chose to starve rather than eat what was forced on us.

There’s also research of our people trying to hunt cows. Lakota people, in order for us to be strong in the ways that the creator meant for us to be, have to eat fresh foods, meaning food that’s recently killed, food that is live from the earth. The leaders in our communities didn’t want to see our people starving to death. They tried hard to eat the cow, but the cow wouldn’t allow the men to hunt, meaning it wouldn’t run. There’s a whole intrinsically spiritual connection between the hunter and the prey. If your prey didn’t run away from you, that was not a good sign for the food that you were going to eat. The thing that I understand about our Indian bodies is the more Indian blood that we have, the more our body is going to behave like a thousand years ago. We cannot be eating the way we’re eating now and expect to be healthy.

Our people have been so removed from our diets and there have been so many forced diet changes that we don’t value our foods the way we used to. That’s the part that I’m trying to educate people about. I think that where food sovereignty starts is educating our own people about the foods that are going to help us live into the future. It’s going to be a lot of work and, and who knows if it will even happen.

Today we identified herbs in our backyard of hinhan wakpa' [owl river] for harvesting, a photograph by Dawnee LeBeau

When I talk about health, we have a lot of relearning to do when it comes to our food. I do this kind of talk with high schoolers. I would say maybe 15 percent hunt or are learning how to hunt, and less than that gather. These are high school kids, so they’re not being taught anything about the foods that we do have access to. On our reservation, we lose a lot of our wild foods because of ranching. Our people don’t even remember eating cattail. Wherever it is growing, the ranchers removed it. Same way with chokecherries, one of our sacred foods. It’s toxic to livestock, so when ranchers come in here and they’re leasing our lands for 50, 60 years, they remove that stuff without even knowing that it’s a food source for us.

Things like that could be a food source, and our people don’t even know. We live in poverty, especially on this reservation. An estimated two thirds of our reservation is dependent on welfare; 80 percent unemployment. How are we going to expect people living in those conditions to concentrate on anything other than feeding themselves and paying their bills and having a place to live? If they don’t have that, we don’t have a movement.

AC and ZM: Can you comment on the relationship between healthcare and traditional medicine?

MG: We’ve never had adequate healthcare. None of our tribal governments are actually our own governments. The IRA (Indian Reorganization Act) created our mini-governments, and then Indian Health Services came into play. Before that, it was all the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which had to follow federal guidelines and was not going to let you have your own healers. They said, we’re gonna bring the white doctors in because they know better. By that time, our people had been so beat down and had experienced so much loss. In the 1800s, not only were we being hunted for extermination, but our spiritual people were being hunted. In fact, here in South Dakota there was what they called an insane asylum9The Asylum for Insane Indians aka Hiawatha Insane Asylum, was a federal facility for Native Americans located in Canton, South Dakota, between 1903 and 1934. A 1927 BIA investigation found that many of the inmates showed no signs of mental illness.. Actually it was a place where they took medicine men and women and locked them up. There was federal policy to terminate any medicine people. How did our people take care of ourselves if our medicine people were gone? We had medicine people who had bear medicine, which can heal bones. We had eagle medicine. We had horse medicine. We had all these different medicines that were able to heal our bodies. Government policy removed all our medicine people. Our people have been burdened with inadequate healthcare since those times. Our daily health has suffered because we are forced to deal with healthcare providers that don’t know how Indian bodies work.

AC and ZM: Can you talk about the history of a food like fry bread, which is so often cooked in Lakota homes and sold at community events like pow wows?

MG: I learned about fry bread when I was learning about the forced diet changes of our people and the realization that wheat is not from here. They were giving us flour and sugar and lard as treaty rations. In the treaty it says that they will provide food for us until we can provide food for ourselves. But that hasn’t happened because they killed off our food supply. How are we supposed to feed ourselves if there’s nothing to eat?

The other thing that was given out in those rations were frying pans and kettles. That’s when we started seeing fry bread. Our people weren’t stationary, we were always on the move; we didn’t have stoves or ovens like some tribes. Just think about all the ways that we had to transition: using lard instead of the fat from buffalo, or your wild game; learning how to eat pig and cow. Anyway, the fry bread situation came out of that time of a forced diet change and a time of starvation.

I visited with elders back in ’99, 2000. You had some who were like, “every Indian woman needs to know how to make fry bread.” Then there was another group of elders who were like, “that’s not a good food for us. There’s too much fat. It’s just starch. Our bodies don’t do well with it.” There was also mention of “this is a starvation food. Our people had to eat this in order to live. That’s why we have it every day.”

There are a lot of different ways to look at it. It wasn’t an original food for us. I choose not to make it because I am a true nutritionist.

Indian taco: fry bread with taco ingredients on top. Credit: Annie Coombs

AC and ZM: How do you currently get food for your family?

MG: I garden. That’s one way that I try to have fresh, live food in our diet. My husband and son hunt. If it wasn’t for the pandemic, we would go to Pierre regularly, or Mobridge. Pierre is an hour south, Mobridge is an hour north, and Eagle Butte is an hour west. And if we have to, we go to Gettysburg, which is half an hour east10Marcella lives near the Swiftbird community.. The La Plant store did open, so now we can get some things there.

AC and ZM: Why do you go to Pierre, off the reservation, instead of Eagle Butte, on the reservation? What options are available on the reservation?

MG: Better choices, cheaper prices. Even though we have thousands of cows being pastured on all our lands, none of that meat goes to our stores. It all goes to a stock exchange somewhere, and then it’s shipped off. There is one local company, Ducheneaux Beef, a grass-fed beef company, but you have to be able to afford it. For some reason, Ducheneaux Beef is not in our stores yet, and it should be.

The Cheyenne River Youth Project does a garden every year. I think once a month, they’re giving away food boxes of fresh vegetables, like pumpkin, squash, carrots, radishes, and potatoes. Our tribe has a food pantry and there’s always food boxes going out to all the communities. Our reservation is highly dependent on outside help. It’s a food desert.

We don’t produce our own food here for our own people, which I think is really dumb. Like Ducheneaux Beef is an awesome operation, but that’s a family business. That’s not tribal, so it’s not benefiting the people.

It’s a shame, because the majority of our population can’t get a job, can’t afford to live in a way that we have a right to live. We’re always on the hustle. We’re not creating space for our own food production, and it doesn’t make sense to me, because we have the land base to do that. We have the expertise to do that, but the tribe has neglected that area. It’s gonna take a lot of work and education. That’s where I focus right now: just educating people on the importance of our own foods and relating it to our state of health.

Biographies

is a Lakota and Dakota from the Cheyenne River Reservation with a master’s degree in nutrition. She was formerly the director of Common Grounds Garden for Little Priest Tribal College, where she served as the primary prevention coordinator of Whirling Thunder Wellness Program for the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska. Gilbert currently works for the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program for the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe.

Her formative years were influenced by the activism of her mother, Madonna Thunder Hawk, and her extended family’s leadership in the American Indian Movement. She was a 17-year-old delegate to the newly established International Indian Treaty Council to Geneva in 1977 and a graduate of the We Will Remember Survival Group. This alternative school, run by and for Native people, was a remarkable tool for decolonizing and healing the intergenerational damage caused by boarding school. She and her mother were recently featured in the film Warrior Women, which explores their identity as Native American activists in the 1970s and today.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.