We decided to consider housing—how houses are financed, developed, built, inhabited—through its relationship to the environment. We turned to cdcb, or come dream. come build., because of its holistic approach to building affordable housing and its attention to not only the home itself, but also the context in which it is built and who it is built for.

cdcb was founded in 1974 to provide safe, affordable housing options for low-income residents of the Rio Grande Valley. It is a community development corporation unlike any other in Texas, in part because of the range of services it provides in-house. In addition to developing affordable housing, cdcb offers financial services and education. An individual can come to cdcb and have many of their homeownership needs met under one roof, by people who have knowledge and experience working in the region. —Lizzie MacWillie, Kelsey Menzel, Jesse Miller, and Josué Ramirez, Brownsville Undercurrents editors

Many Rio Grande Valley residents live in colonias, unincorporated neighborhoods that lack basic infrastructure like streetlights and adequate drainage. Credit: Veronica Gaona

Kelsey Menzel interviewed Nick Mitchell-Bennett and Edna Oceguera in 2020.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Kelsey Menzel (KM): Your work is not just about the four walls of a house, it’s about the home and the space outside the house, as well. Can you talk about that?

Edna Oceguera (EO): Our families and the families that we help have had many struggles, growing up poor. More than just the house, it’s the importance of having a space for a family. We have to take into account the struggles low-income families go through, as well as what they dream about, where they see themselves when they get their own homes. For many, it’s being able to have a BBQ in their yard. That’s what I think is important, because that’s what they have dreamed about for years. Many have had to live with their in-laws, their families. Often they’re all in one home altogether. So the most important thing is having their own space, what’s going to make them happy to go home to.

KM: Can you talk about how your projects address community-wide concerns like drainage?

Nick Mitchell-Bennett (NMB): In the early days of affordable housing, say, 25 years ago, it was just about building this box—like, we are going to do the minimum to try to approach environmental issues, lighting, landscaping issues, whatever. But we (cdcb) saw that we could do more. Even before Edna and I took over, we as an organization understood that’s not what it’s all about.

In 1997, we built the first neighborhood that actually had sidewalks, which weren’t required in Brownsville at the time. We knew people needed to be outside, needed to be able to transport themselves—and not only with a car. We also built the first subdivision that actually had a park, which was later used as part of a drainage solution. And then the City told us that the park has too many trees—“We don’t want it, you need to keep it because we don’t want to mow around all these trees.” So we organized the community and they forced the City to take it from them.

Even to your first question, about how it’s more than just a house: working in drainage or any other environmental issue is really important. We live in a river delta, we are not a valley, despite our name. There is not a piece of property in the RGV that is not in a flood zone. Not one. And we’re growing in size and people, which means we’re putting in more concrete and impervious surfaces. We need to get not only us to do this work but also to encourage counties and cities and the transportation department to be thinking, how do we do this better, and how do we do it more beautifully? We’ve got to be moving water: that doesn’t mean it’s not always going to be out of the street, and people need to understand that. The streets are part of the drainage solution. We tried to do that with [nonprofit community design center] bcWORKSHOP in the past, teaching people about drainage, and how it all works. And that every person has a personal responsibility. Flooding is not just the County’s or City’s fault. If everyone takes care of their responsibility, then it’s doable. But we don’t teach people this as a society. People don’t understand that it’s everyone’s job, so someone may decide to cover their entire property with concrete and then expect the City to distribute 100 gallons of water every two minutes when it rains.

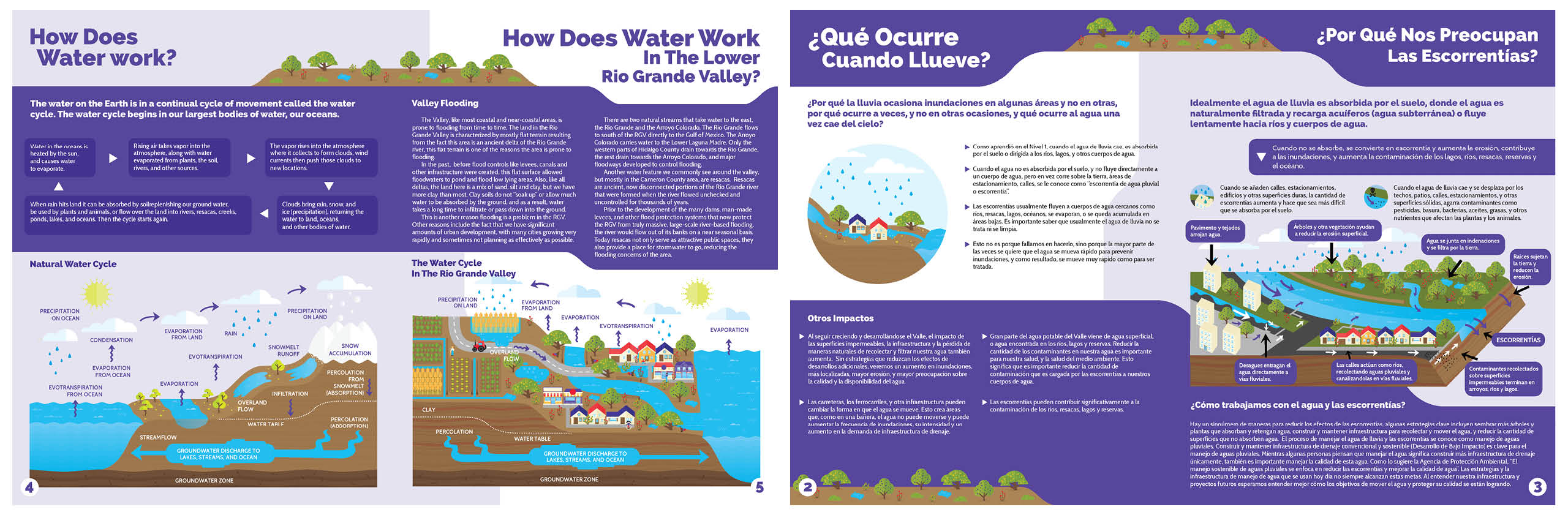

LUCHA (Land Use Colonia Housing Action) was an organizing tool developed in collaboration with LUPE, ARISE, Texas Housers, cdcb, and buildingcommunityWORKSHOP. The materials covered five topics, including drainage. Each topic had three modules that residents would cover with community organizers, building knowledge and capacity around these different areas to equip residents as they organized their communities. Left: shows one of the pages from the Drainage Module 1 booklet, introducing some of the reasons why the area is so prone to flooding. Right: An illustration from Drainage Module 2 describing water runoff. Learn more about LUCHA in the Organizing for Infrastructure feature. Images courtesy of buildingcommunityWORKSHOP. Download the full Drainage Module 1 booklet. Download the full Drainage Module 2 booklet (in Spanish).

View the full library of resources developed by LUCHA.

EO: We’ve set a good example of that in [our low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC) developments] La Hacienda Casitas and Los Olmos. We have taken officials over there to see it and the drainage solution that we have there: everyone is shocked when they see how it works there. That’s part of the introduction that we need to do. It’s been proven, and those two projects don’t flood. Those projects have been a very good step going forward, teaching the community and officials where we need to be in drainage.

KM: How has the structure of your organization changed over time to address the needs of the communities you work in?

NMB: cdcb has a certain skillset. We can build things, we can lend money, and we can manage projects. One thing we’ve done to grow that skillset is adding partners and other groups to work with us and beside us, and even lead us. That’s been new, like working with [bc], we never really thought about design and how important design and planning were until 10 to 12 years ago, and how we could employ those aspects in the work that we do. So now we think not just in terms of the built environment, but more about trying to build wealth for communities. Just a house is not going to build wealth at a community level, so our organization has changed to adapt new ways of thinking that only enhance our original goal to build houses.

Operationally, Edna can tell you it makes things much more difficult.

EO: [laughing] It does. Nick thinks of good projects, and I’ve got to think of ways to get them through. But there is always a way. The need is there, and the growth in what we do shows that we can get it done.

KM: Now, can you talk about MiCASiTA, your grow home model for affordable homeownership, and the evolution of that work? What were you responding to?

NMB: We are responding to two things. One, the fact that the amount of money for subsidies to assist buyers has been declining substantially since the ’90s. It varies year to year, but it’s declining overall. That means home lending, CDBG (Community Development Block Grant) money, and USDA—any state/federal funds that are used to do affordable housing for low-income people—has been declining. Not only that, but there are more needs for that money here in Brownsville and the Rio Grande Valley.

Prior to 1994, cdcb accessed about a quarter of the CDBG money as part of doing affordable housing. We now no longer get any CDBG money because the City needs it for other things, like streets in low-income communities, water treatment plants, fire engines, EMS things. The need is bigger and the pie is smaller.

Simultaneously, there was an increase in the cost of building a home. Over the last 10 to 11 years, housing costs have gone up 31 percent in Brownsville, and incomes have only risen about 16 percent. The subsidy is reducing and the gap is increasing.

At the same time, though, there was some push to get low-income folks mortgages under Duty to Serve/FHA, Fannie, Freddie, and those GSEs (government-sponsored enterprises). My thinking was: We have this problem, and this opportunity. Why don’t we apply this grow home model, which we had developed with [our disaster recovery model, RAPIDO] to this? To let people do what they’ve been doing for centuries, building houses piece by piece. Why don’t we do that in a more controlled, sustainable, healthier way for people?

When businesses in Brownsville sell high-dollar things, one of the questions is, “Can I get this on payments?” Why not use this same mindset to meet this need? Using our assets, our culture, and the economic realities. MiCASiTA came from the need, and the benefits that we have, as well as the cultural and environmental high points of our area.

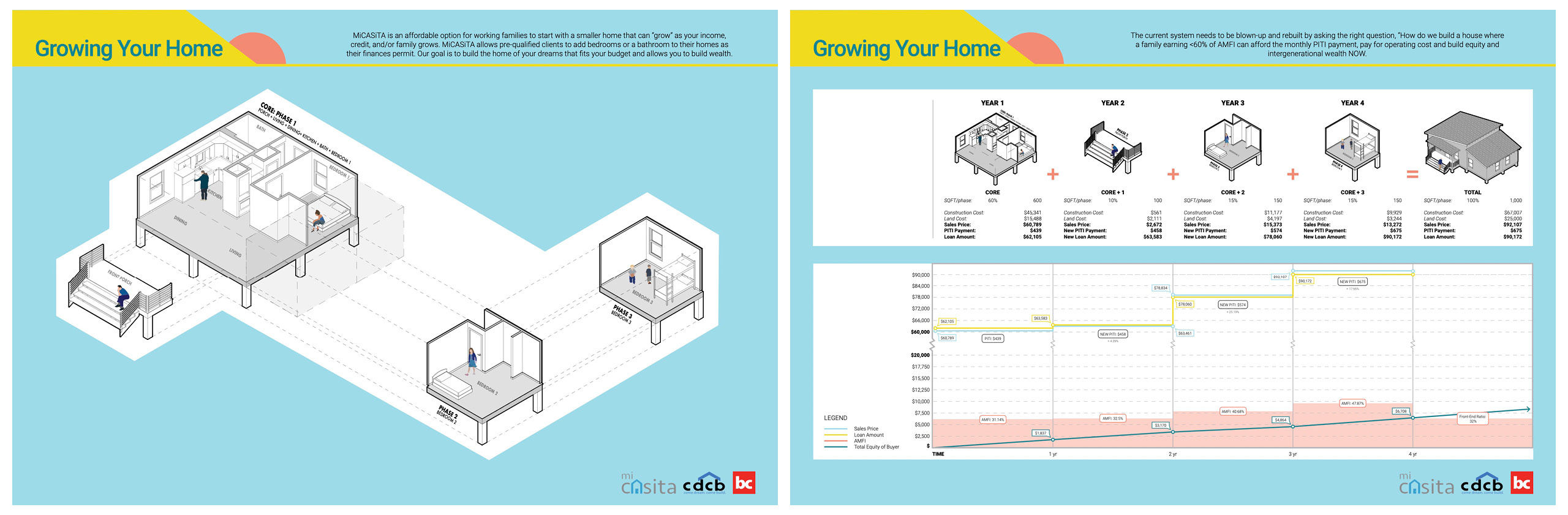

Left: MiCASITA allows for a family to start with a “core”, which includes a living space, a kitchen, bathroom, and bedroom, and grow it over time as the family’s personal and financial situation evolves. This diagram shows the possible phases of growth. Right: As a homeowner adds to her residence, she builds equity. This graph shows the relationship between the costs of construction, loan amounts for the phased build, and the change in value of the home throughout the process of growing the residence. Credit: cdcb and buildingcommunityWORKSHOP. Download the MiCASITA infographic PDF.

KM: What is the public perception around climate change? What about the perception of the word “sustainability”? How does the perception of these words/concepts influence your work?

EO: Our families like the climate change and sustainability side; that’s what they’re looking for, something that’s sustainable. I think they like designing their own home into something that’s sustainable for them. But their main concern is having a home they can afford. We have them go through a financial security process to make sure the home is affordable, and that they can sustain their life around their home. When we talk about sustainability, that’s what’s in their thought: finances. We talk about the environment, but the main thing when they walk into our office is a home that they can afford. A home that is going to last. With our culture here, our clients buy a house, and that’s their house; they’re going to stay in it for years.

KM: What is the general feeling surrounding climate change? Like: storms are getting worse, I need to have my home be prepared—is that a common concern for folks living in particularly vulnerable flooding areas?

NMB: I think the younger generation understands the connection between climate change and shit getting worse. The older generation often thinks of it like, “Wait, we’ve had four hurricanes and I need to make sure my house isn’t going to fall over.”

EO: Yes, the older generation knows what it takes to get prepared for a storm. And it’s always a concern.

KM: What are the main differences between housing opportunities and challenges in the Brownsville urban core versus nearby colonias?

NMB: A city like Brownsville or any other PJ—participating jurisdiction with HUD—gets an annual allotment of money from HUD. Colonias are not part of a PJ, they’re part of the state’s PJ. So they have to divvy up way less money.

Also, in the colonias, the level of infrastructure improvement affects the affordability of that house. If you get into a colonia and there is no sewer system, we’ve got to put a septic in, or we have to make sure the sewer is installed, and that eats into the cost. In the city of Brownsville, there is already a sewer system. So that cost isn’t there.

EO: Incomes, too. Incomes in the colonias are less than in the city of Brownsville, at least to our clients. From what we see from our clients who walk through the door, you’re making 10 percent less if you live in a rural area versus the city.

NMB: Then you have a place like Cameron Park, which is a colonia, a complete donut hole in the city of Brownsville, no access from the state or from the city. The State considers it urban, not rural. And the City says it’s not in their district. They can’t get USDA money, because it’s no longer rural. So they don’t get any money. They have to contract with the City for fire and police. It’s literally in the middle of the city, but they don’t have any access to the same stuff. So it’s not just a lack of affordable housing, but it’s all these other little things that are tacked on to make their lives a little bit harder.

KM: What is needed for an organization like cdcb to be successful?

NMB: This sounds so lame, but it’s money.

EO: That’s exactly it. Money.

NMB: You get so many people coming to us with great ideas, and I always love to hear them, but we’ve already got smart people who live here in the Valley, and who work for cdcb and our partners. Just give us the money to figure out how to do this.

Increasing homeownership is easy: we just need down payment assistance. Interest rates are at 3 percent now. You can’t create a newfangled loan product better than a 30-year mortgage at 3 percent. You can’t get better than that, but the problem is getting the family into the home. How can I get $10,000 per unit for down payments so I can get somebody who makes $9 an hour—and they’re not going to get a raise, they live in the Rio Grande Valley—into a home?

EO: Incomes don’t go up, just construction prices. So how do we meet that demand? How are they going to afford a house when the construction prices go up but their incomes don’t?

NMB: We’ve got this Lantana project that is stalled because lumber prices went up. We’re not putting anything newfangled or fancy on it. The cost of constructing a house went up. But my renters’ incomes haven’t gone up.

We have to bridge that gap. But no one sees that by bridging that gap—what’s the positive impact for the community because that house was built? They do better in school, their health is better, they pay property tax, they’re shopping at the store, all these things are there. $15,000 in down payment assistance gets paid back to a community within five to six years, but we have to get people to see that.

Biographies

is the executive director of cdcb | come dream. come build. and the administrator of the RGV Multibank (RGVMB), a community development financial institution (CDFI) headquartered in Brownsville, Texas. Prior to taking the position of executive director in 2008, he served in multiple positions within the organization. During his tenure he has led the cdcb team in the development of over 3,000 affordable homes, raised over $75 million in public and private grant funds, and deployed over $100 million in private lending capital and equity. In his role as administrator, Mitchell-Bennett led the RGVMB to be the first CDFI to join the Federal Home Loan Bank of Dallas, creating the CASA Loan product. In 2011, the RGVMB launched the Community Loan Center, a small-dollar alternative to payday lending products. The RGVMB has franchised the CLC model into 22 markets across the country, allowing the entire CLC franchise network of lenders to originate over $60 million and conduct over 58,000 transactions. Mitchell-Bennett has a bachelor’s degree from Tabor College, a master’s degree from Eastern University, a housing development finance professional certification, and has completed the Achieving Excellence program at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. In 2015 he was recognized with the Texas Houser of the Year Award.

oversees cdcb’s administration, finance, and loan operations, directly supervising the organization’s senior staff and managing day-to-day operations. Prior to cdcb, she had over 21 years of banking experience with Mercantile Bank in various areas, including overseeing loan and credit operations.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.

Note: Josué Ramirez, one of this report’s editors, is currently an employee of cdcb.