From Indigenous resistance against colonial oppression to folk heroes who fought back against state-sanctioned violence, self-determination and community resistance are integral parts of the region’s history. These brave actions were precursors to or catalysts for social justice movements that define generations of the Rio Grande region. The Farm Worker and Chicano Rights movements of the 1960s and 70s paved the way for organizing around public infrastructure and land-use equity in colonias—informal settlements often lacking infrastructure—in the 1980s, 90s, and more recently.

La Unión del Pueblo Entero (LUPE), a community-organizing nonprofit founded by Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez in 1989 and established in the Rio Grande Valley by current director Juanita Valdez-Cox in 2003 has been a force behind significant achievements in the region’s fight for social justice. A major focus of LUPE has been equitable land-use practices and access to public services such as street lighting and drainage infrastructure for colonia residents.

This feature explores the ideas of Martha Sanchez, the coordinator for the organizing department at LUPE. Sanchez has spent years thinking about the region’s infrastructural needs and the ways in which residents might organize for greater control over their built environment. In this interview, she explains how to mobilize communities around local issues. —Lizzie MacWillie, Kelsey Menzel, Jesse Miller, and Josué Ramirez, Brownsville Undercurrents editors

Josué Ramirez interviewed Martha Sanchez in 2020.

The following is a description of their conversation edited for length and clarity.

When I began my conversation with Martha Sanchez, I asked how everyday individuals could have a say in infrastructural improvements in their communities. She responded that one should first consider the barriers that currently prevent people from engaging in the processes that define and create the built environment.

Martha Sanchez (MS): For people to be a part of [improving their communities], it [has to be] a process. When people have been poor or not taken into consideration as a human being, it is a devaluing factor in their minds. That is the hardest thing for an organization to address: to build up people’s ability to believe in themselves—something that has been taken away from them [due to] different factors, [such as] poverty, discrimination, etc. This is a value that they should have as a human being. It is a process to help them believe that they have a voice: a say so in their future and how their future can be changed . . . if they get organized with other people and learn how to use their voices collectively. So, it’s a process but it happens. It’s proven that when we help people rebuild the belief in themselves then they can get organized and be a part of the solution—building change in their communities. So that is first in answering, “How do we organize people?”

Building community through investment in individuals, trust, and a shared understanding of collective strengths is imperative to the theory of change that is the foundation of LUPE’s efforts. The organizing model is based on committees that collectively prioritize the issues they want to tackle, as Sanchez emphasizes.

MS: Members have to be a part of the process, so they can start feeling empowered. When they have decisions to make, when they choose what to do, how to do it, that is essential in empowering people.

The only way to get people to be comfortable speaking about solutions is if they first understand the problem, Sanchez explained. Knowledge and skill are key to empowering individuals and implementing campaigns. However, they’re often difficult to come by in the region.

MS: Because we are in such a poor area in the Rio Grande Valley, the way to effect change is to build allies with others that have expertise in different areas. We don’t have the knowledge in every area, so as an organization we try to leverage these collaborations for the people who are typically isolated, people who do not have access to the organizations with the expertise.

Many times we have had to find experts. [For example,] in the drainage campaign we had to work with engineers to know why these particular colonias flooded. We don’t want to be an organization that just complains, because a lot of people complain. We want to complain with a solution, and we want people to understand the problems so they can feel empowered to speak with authority.

Maria Romero, a community organizer at La Union Del Pueblo Entero (LUPE), organizes different Rio Grande Valley neighborhoods to push campaigns and bring long-lasting infrastructure changes in her community. Romero said, “In the meetings we respond to injustices facing working families, farmworkers, and immigrant communities by prioritizing issues and then developing a plan to address them.” Credit: Veronica Gaona

In 2013, LUPE partnered with A Resource in Serving Equality (ARISE), a colonia-based organization focused on women and children; Texas Housers, a statewide policy advocacy organization; buildingcommunityWORKSHOP, a community design firm; and come dream. come build., formerly the Community Development Corporation of Brownsville. The collaboration yielded many transformative projects, including Land Use Colonia Housing Action (LUCHA). LUCHA was a multistage, multifaceted process, “to build resident capacity” through “engaged conversations with local and regional experts.”1bcWORKSHOP, “LUCHA,” accessed March 24, 2021. A cohort of colonia residents collaborated with organizers, policy experts, planners, designers, and scholars to develop a policy agenda based on local needs. Residents completed a yearlong phase of platicas, training and organizing activities that culminated in the beginning of the drainage equity campaign. Sanchez described to me the questions the project first asked.

MS: What are the solutions and problems in a colonia without the proper infrastructure, and what is the proper infrastructure? That is what colonia residents had to learn: to be able to sit at the table with public officials and also offer solutions to these problems. I don’t think we can do it any other way. Once you organize the people, get them to be experts on the field, then sit down with the proper authorities . . . but it is also all that learning process that happens, [however] it can work.

Left: Colonia residents redirect water after the collection of rain in their front porch. Right: Flooded streets in a colonia. Credit: Veronica Gaona

Sanchez emphasizes that although not all individuals have formal training in these topics, everyone has some form of expertise. Just as residents learn from the professionals, experts learn from colonia residents.

MS: [Many professionals] do not know how these issues affect people in real life, so the impacted people share the information with them in this back and forth exchange. [This exchange of expertise] becomes so important in getting the change they need in their colonia.

Empowerment through knowledge was extremely important for LUCHA participants, the majority of whom were immigrants with varied levels of educational attainment. When they saw that flooding caused by the lack of drainage infrastructure impeded their ability to get their kids to school and take advantage of the educational system, this issue became a clear priority for community organizing and action.

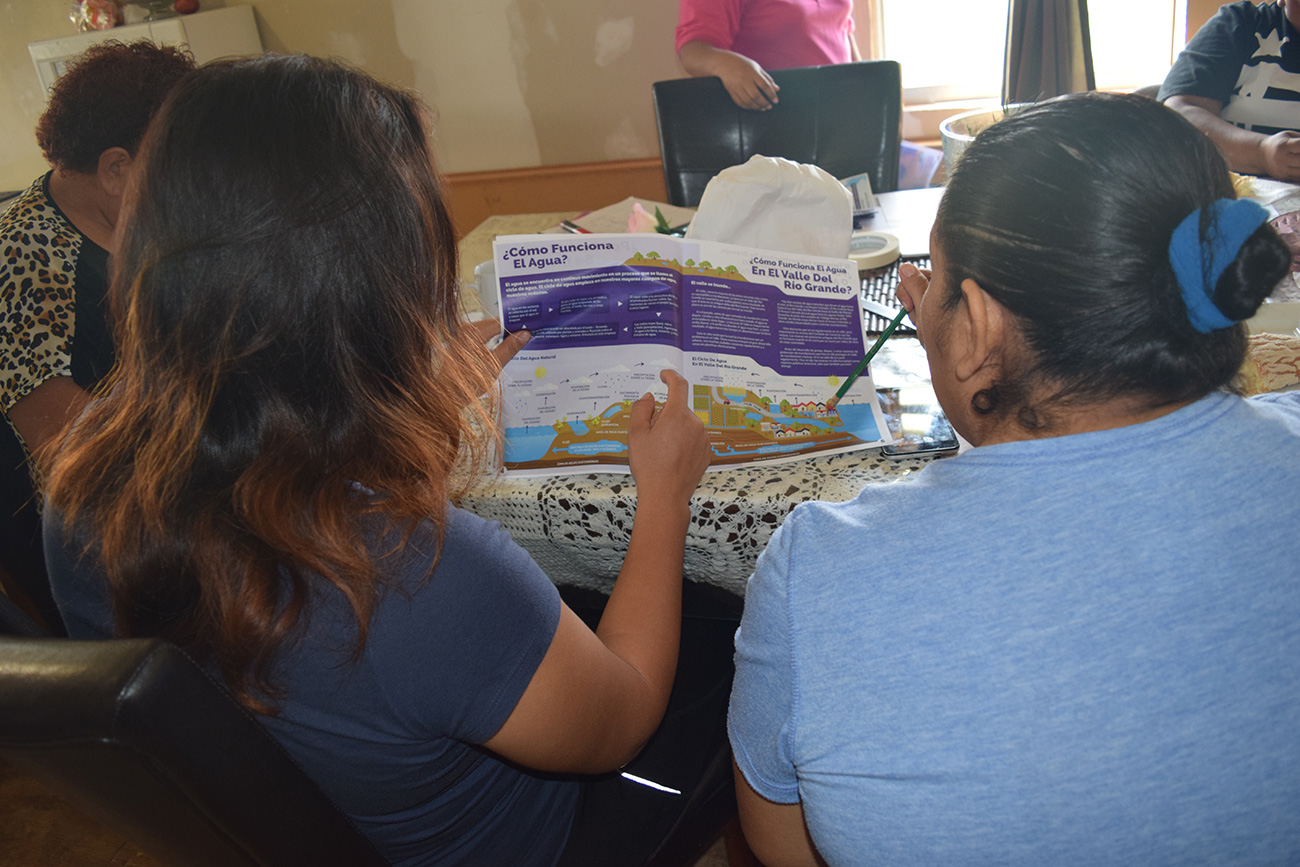

Colonia residents study a drainage guide, part of a set of educational materials relevant to colonia struggles put together by LUCHA. Credit: buildingcommunityWORKSHOP

The lessons learned from organizing around drainage have informed work on another pressing infrastructure issue in the colonias: limited internet infrastructure and low ownership rates of computers and tablets. The pandemic has made these connectivity and technology gaps painfully obvious. Sanchez points to a case of one family with five siblings and their mother all dependent on the WiFi from a single phone.

MS: We knew that infrastructure for the internet was an issue but it has never been so clear until now that children have to do schoolwork at home. They realize they have nothing to work with, and [residents] see the lack of the internet as another barrier for their family’s education. This is something that affects families right now.

The gap in technology has also put students from low-income households at higher risks of infection during the pandemic when families with little access to technology have had to place them back in schools, where health risks are higher.

Understanding the interconnectedness of issues like these is important to LUPE’s work around community organizing. But helping residents see that infrastructure inequity affects health, educational attainment, and other socioeconomic measures can be difficult.

This is the case not only in the colonias, but in more urban areas as well, as was evident in a recent campaign on public lighting. The campaign had two primary goals: to develop relationships with local allies and City officials, while simultaneously engaging the residents to put pressure on public officials.

MS: It is always hard for us to organize people who are renters [in other words, city dwellers]. We haven’t found the secret, but a lot of people in the city care about people in general. There are good individuals everywhere, so we appeal to that sense of caring for others and being in it together.

We have to make campaigns that are going to appeal to the good of the people of the RGV [Rio Grande Valley]. I think that was very clear in the public light campaign when we created a social media campaign that highlighted union members’ children who were in the dark. [That was] a good approach to get people in the city to support this campaign.

It had to be very strategic; it did not happen by accident. We cannot create change if we leave anybody out. We need everybody when we are talking about big changes. The light was a huge issue with many, many components, so we needed a lot of support. It took us many years but we were able to do it because we included many people, organizations, expertise, public officials from the cities and from the county, to support this and buy into believing that this was something that was going to benefit everybody.

Indeed, many of the infrastructure improvements that LUPE has been a part of expand beyond the colonias and benefit many others in addition to those who organized. In 2017, the group scored a major victory with amendments of the Model Subdivision Rules that regulate neighborhood development in Hidalgo County, a nearby county with the largest concentration of colonias in the region. The changes to the regulations made public lighting a requirement for new subdivisions and improved drainage standards, vindicating Sanchez’s belief in organizing.

MS: A lot of colonias’ infrastructure has been fixed because of that pressure, and that loud, organized voice got public officials to respond to the needs. It seems if people do not get organized and do not put pressure, things will not happen out of the goodness of public officials’ hearts.

The loudest voice gets the piece of pie so we have to organize people to be that louder voice.

Sanchez believes that individuals must be given space and incentives to lead for the long haul. In her experience, this requires putting people in front so they will be able to receive recognition and see themselves as the ones who created the change. She recommends celebrating small victories and always looking for the lowest-hanging fruit.

MS: Sometimes in the low-hanging fruit is where you find that small wins affect larger victories.

Biographies

leads La Unión del Pueblo Entero (LUPE)’s team of community organizers, as the coordinator for the organizing department at LUPE’s Brownsville, Texas chapter.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.