Brownsville, Texas

Taller de Permiso / Permission Workshop

To complement the feature by the socially engaged artists collective Las Imaginistas, we wanted to highlight one of their projects that explores the economy of Brownsville. In this essay, Las Imaginistas cofounder ChristinaMaria Xochitlzihuatl Patiño Houle reflects on Taller de Permiso (Permission Workshop), which looks at the permitting systems and regulations around street vending and the ways in which they help shape public space and economic development in Brownsville. —Lizzie MacWillie, Kelsey Menzel, Jesse Miller, and Josué Ramirez, Brownsville Undercurrents editors

Dina Nuñez (right) sells flower crowns within the Taller de Permiso (Permission Workshop) led by Las Imaginistas. The project is an arts and economic idea that seeks to challenge the local municipal permitting process. Nuñez said, “We work this project to sustain ourselves, even though a lot of money does not come out of it.” Credit: Veronica Gaona

On the border at the Gulf of Mexico, the Brownsville area is one of the most biodiverse regions in the US, and its cultural identity is shaped by its proximity to Mexico. Over 98 percent of the population identifies as Latino or Hispanic. In pre-COVID-19 times, many people crossed the border daily for work, school, and family. Brownsville is a city full of immigrants and families with mixed immigration status (meaning one or more individual in the family is undocumented). Many immigrants are entrepreneurs; however, because micro-entrepreneurship is not officially sanctioned in the RGV, these low-income vendors face high fines for developing their own businesses. Under existing law, immigrants in the RGV who lack proper permits could be deported and sent back to dangerous conditions in their home countries if they were to be arrested for street vending. Local law enforcement can collaborate with immigration enforcement, which has resulted in community members being deported for infractions as small as having a broken tail light. The connection between this scenario and the life-or-death impact of racist policing throughout the nation is not lost on the Imaginistas.

At the moment that this text is being written, in the summer of 2020, the US is in the middle of protests surrounding the death of George Floyd and many others at the hands of police. The intersectionality of safety, community planning, and economic development is imminently evident right now. The United States is a nation built on stolen land with stolen labor, and the border region understands this problem in a deep and present way. Brownsville is a town named after the military fort that helped further colonize the region. The city’s economy is largely influenced by the militarization of the region, the extraction of natural resources through dangerous practices that are in direct opposition to Indigenous interests,1Read more in the Threat of Fracked Gas Exports in the Rio Grande Valley to learn how Indigenous and environmental activists are fighting a proposed fracked gas pipeline and terminal installation. and the continued militarization of the border space through the policing of migrant bodies. A critical component of reimagining equity in the region is understanding and reimagining its economy.

When Las Imaginistas began our work in Brownsville, founding directors Celeste De Luna, Nansi Guevara, and I wanted to use art as a tool to address the needs of historically marginalized groups in the region. The group’s first two major projects grew directly out of relationship-building with community activists and a series of interviews with frontline community members. In these early community interviews the group saw two things: 1) local legislation did not address the real economic or cultural needs of the community, and 2) the voices of historically disenfranchised groups were being systematically excluded from decision making processes.

Our femme and nonbinary collective worked to create a process of non-hierarchy in our internal processes that reflected the values of our collaborative art practice. Initial interviews with community partners were conducted with residents, activists, and artists. Interviews happened on the street, in house meetings, and through organizer focus groups. Meetings were small, personal, and oriented towards healing and relationship building. Each gathering focused on a process of exchange. In one house meeting, participants took salt baths while drawing their dreams for the future of the region and eating pan dulce (traditional sweet bread).

Sustainable economic development quickly became a core area of focus for the group. Immigrants’ visions for the future of the region included access to shared resources and non-extractive relationships to the environment. One interviewee shared a vision for community housing featuring indigenous plants of the region. These types of ideas reflected a larger community vision for a just transition towards more sustainable lifeways.

The group conceived two multi-year projects with different tactics to address these core concerns. Our intention was to shift the public imagination on how just and sustainable economies could be built and embodied in the region from the micro and macro lens: Taller de Permiso (Permission Workshop), which re-envisions the future of micro-entrepreneurship, and Hacemos La Ciudad (We Make the City), which resulted in a comprehensive plan for the future of equity and justice in the region, including a reimagining of the region’s economy.

Taller de Permiso (Permission Workshop)

Taller de Permiso’s name is a play on the word permission, literally translating to Permission Workshop. The program seeks reform for outdated vending regulation as a strategy for building economic reform while also questioning the colonial framing of permitting. Municipal permitting is a formalized process of privileging certain bodies and cultural practices over others. Though it can create standards that help to ensure community safety and wellness, this framing has historically been weaponized against marginalized communities. Taller de Permiso decenters the municipal governing bodies as the only authorities capable of giving permission and frames residents and vendors as critical agents in shaping the future of economic justice in the region.

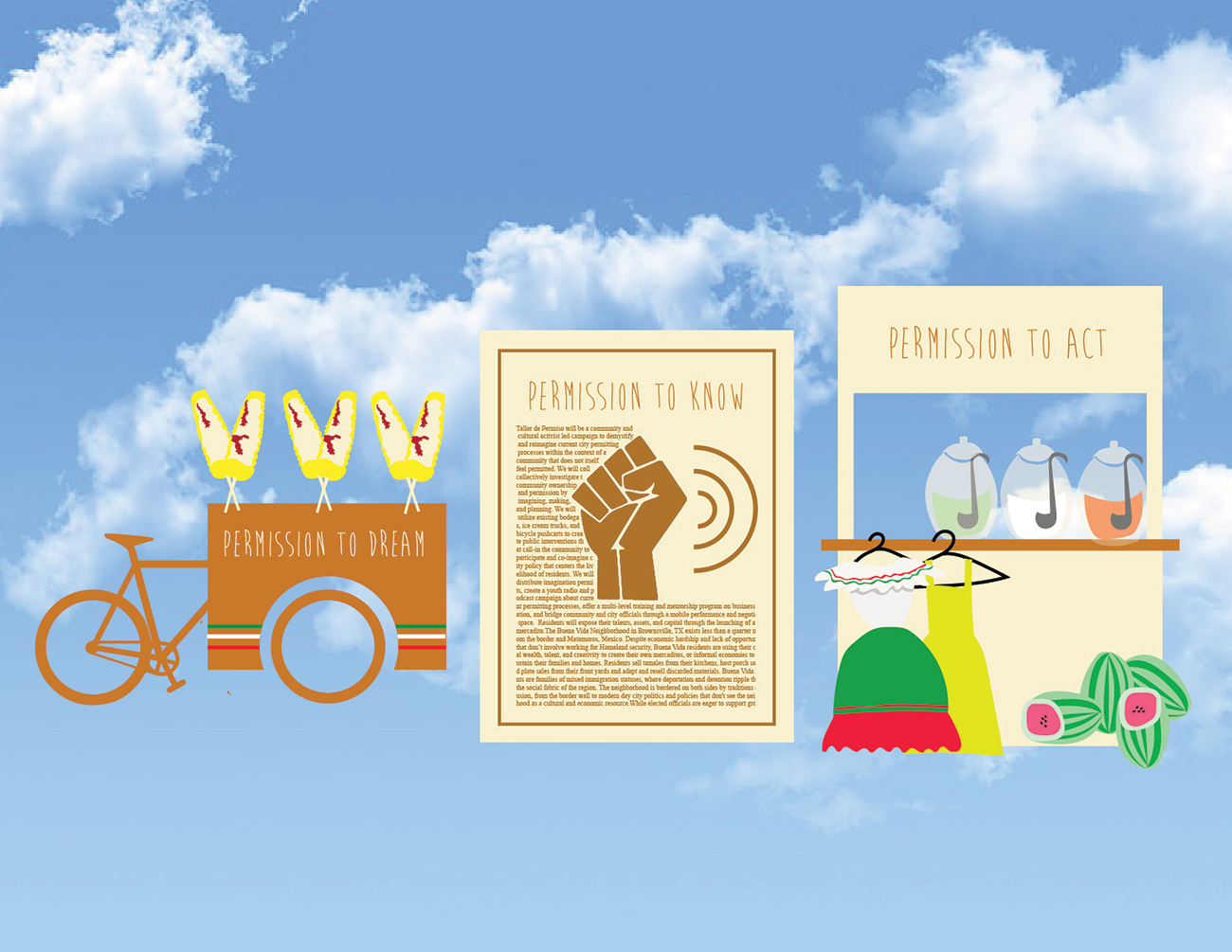

This project is divided into three stages that mirror the Imaginistas’ way of working:

1. Permission to DREAM: cultivation of imagination

2. Permission to KNOW: capacity building and resource sharing

3. Permission to ACT: embodiment and action

Each phase is interwoven into the next. Instead of functioning as standalone, iterative stages, the processes are continually addressed as new ones are integrated. Dreaming is cultivated throughout Knowing. Knowing is activated during Acting.

Permission to Dream

The core focus of Taller de Permiso is to look at the criminalization of small business development, especially as it impacts very low-income communities. In this phase, members of the Buena Vida neighborhood imagined the future of permitting regulation and accessibility for new vendors to navigate municipal coding. Participants were asked to draw and articulate what their dreams for economic justice in the region would look like. Permission to Dream resulted in a march for the region’s dreams, a Sueño (Dream) Parade. The parade built on the region’s rich tradition of marching for economic justice. The Rio Grande Valley is where farm workers have organized and mobilized for decades, fighting for better wages and working conditions. The dream parade followed in this legacy as participants marched for their vision of a community that better reflected the economic interests of its constituents.

Participants in the Sueño Parade, part of Permission to Dream. Photographs courtesy of Las Imaginistas

Permission to Know

The foundation of this project was constructed on reclaiming the public imagination as an act of community organizing and radical resistance. Another component of this phase was working with participants to create and distribute creativity permits through a number of art engagements. At these events residents would write their dreams for the future on certificates hand printed with a tortilla maker. Strengthening the public imagination and expanding community capacity to dream is a foundational component of the Imaginistas’ work and collaboration with community.

Building on the foundation of Dreaming, Permission to Know focused on group capacity building. The phase had three audiences and strategies for knowledge distribution: 1, would-be micro vendors; 2, existing micro vendors; and 3, young people new to community organizing.

1. Business Incubation

Las Imaginistas partnered with the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley’s small business incubator to train 30 people with an interest in starting a new business or an existing business they wanted to advance. One of the vendors said, “I never went to college and I always wanted to go. Taking the class was like being a business student. It helped me see how to make my ideas a reality.”

2. Community Organizing + Vending Opportunities

Las Imaginistas created a cohort of vendors who meet together regularly, create strategy for outreach to elected officials, and regularly vend at local markets. This group of vendors has built a community of support. They ask one another for help, are connected through group chat, and have taken care of one another during COVID, providing emotional support and outreach during these months that have been especially challenging for small business owners. The infrastructure and community is particularly important as the group works to fight systemic and legal challenges that can feel bigger than them and mystifying in their opaqueness. By building relationships, vendors understand the commonalities of their experiences and see them as an indication of a problem with the larger system, rather than something they should be able to fix on their own.

For example, most of the vendors speak only Spanish, but all City meetings and City regulations are written in English. When an individual confronts these language barriers, she may feel like it’s her fault for not speaking fluent English, but when 10 people confront it together, they begin to ask, “Why is the city not meeting the needs of our group?”

3. Deciphering, Decoding, and Leadership Building

A cohort of young people was formed to visit municipal leaders, conduct research on the history of deregulating micro economies and street vending, and build culturally relevant visual tools to help the community understand existing small business code. The work of this group resulted in a poster-style guide that helped decipher the existing permitting code for market vending. The style celebrated the Mexican block printing used both for newspapers and community posters throughout the late 1800s and early 20th century. Youth participants learned about the cultural and historical importance of woodcut printing, and also how to conduct community interviews. Stories they collected from local small business vendors were celebrated through the visuals produced during this phase. Youth learned to collaborate with, learn from, and celebrate their neighbors while also using their skills and knowledge to provide a service to their elders: decoding local regulations to help them in navigating existing laws.

The candidness and energy of intergenerational collaboration was critical to alliance building and the overall success of the stage. In one interview with the city manager, a young person asked, “But why did you make street vending illegal?” The bluntness of the question stumped the city manager and he took some time to gather a response, which was that there was no law making street vending illegal—but because there was no law regulating it, practicing it fell outside the law. This moment was particularly important both for the young people and for the city manager, as both stepped outside their normal roles of engaging with the other to try and invent a new space for discussion and possibility.

Workshops held during Permission to Know. Photographs courtesy of Las Imaginistas

Permission to Act

Permission to Act is a phase of radical embodiment and rehearsing the muscle memory of liberatory futures. This phase integrates the knowledge systems developed through the DREAM and KNOW phase into a stage oriented around thoughtful, strategic, and intuitive action.

The phase has three core components:

1. The launch of a community co-op

2. Implementation of a pilot mobile vending zone in the Buena Vida Neighborhood

3. The creation and launch of a mobile negotiation space

Co-operative International Thought

Based on community interest, the changing landscape of sustainable economic futures during a global pandemic, and synergetic partnerships with aligned regional labor organizers, the Taller de Permiso vendors are working with Border Workers United to launch a women-led community co-op. The organization will have a storefront in Buena Vida as well as a digital store.

The vendors will incubate their co-op over a year-long fellowship program. During this time they will collaborate and learn from women-run vendor co-operatives across the globe. The connections built through these trainings will also provide the foundation for cultural exchange and networked economic empowerment. The resultant products will represent thought, cultural, and material collaborations between the different communities. The action of shared, networked learning will in and of itself be an act of resistance to neoliberal legislation that has destroyed the economic fabric of communities worldwide. Instead of letting community members be victims to trade agreements (such as NAFTA), Taller de Permiso will represent grassroots resistance to international trade agreements that ignore regional impacts.

Recultivating Mobile Vending

The youth reporters in our Reportistas program discovered that mobile vending was formerly permitted throughout Brownsville. As recently as the 1950s, vendors could sell their goods on the street in Brownsville or Matamoros without much difference in regulation. Furthermore, other cities throughout the US have modeled a renaissance of mobile vendors. In New York and California, mobile street vending has been an important issue with small wins for the immigrant communities of mobile vendors.

Through a collaboration with the nonprofit Civic Arts, Las Imaginistas commissioned a report on how to initiate a mobile vending pilot project in the City of Brownsville. Throughout the phase of ACT, vendors and community organizers will advocate for the implementation of this pilot program.

Imagining the vending possibilities. Images courtesy of Las Imaginistas

Forward Looking

The Taller de Permiso program merged in 2020 with Border Workers United to collaboratively develop the region’s first cooperative. The fellowship program is incubating 10 microvendors and will result in a women-led artisanal cooperative in the Buena Vida neighborhood. These vendors are also advocating for new permitting legislation in Brownsville that would expand the types of goods permitted to be sold in houses and small storefronts, thereby lessening restrictive regulations for low-income vendors. This type of change will open new pathways for economic justice for immigrant, low-income, and women-led businesses.

Conclusion

The future of sustainable economic development in a region working to decolonize its collective and spatial identity is complex. Vendors in the region have fought to adapt to a colonial capitalist system at odds with Indigenous understandings of progress—a fight since the beginning of the genocide of Indigenous people. Taller de Permiso is organizing vendors for a better economic future of low-income immigrant communities. But more importantly, it is incubating a cohort of women, femme, and nonbinary individuals who are defining sustainable economic development on their terms.

Blanca Delgado, Executive Director of Border Workers United, explains her vision of economic justice:

Our struggles are so normalized internally that we don’t see [them as] struggles. When art makes it visual it’s like, ‘Oh my god, I see myself. That’s a reflection of our struggles.’ Especially … the art piece of the paletero [ice cream vendor], it’s envisioned right there, all the feelings and someone glorified him as he needs to be. Because we see a lot of pictures of people in suits and offices and what have you, but when it comes to our local art, it is about the people who are invisible. So when they see that picture of themselves they think, ‘Wow someone is thinking of me, someone values my work.’

We can empower people through art, because they will see themselves, they will see the struggle. I was also thinking of the moms … I would remember my grandmother. She would have my brother hooked to the hip and then cooking for the rancho. A lot of our struggles are intertwined with caring for the family, and that comes to the moms. That is another thing, that moms are still invisible. They are like, ‘I really have it bad. I have to be a wife, a mom, a sister, a daughter, but I also have to keep working.’ It is a different kind of work, one you don’t get paid for. So with art and that empowerment they will be pushing.

What I have seen is there are a lot of people who use destructive methods of de-stressing, but if you use the art, where they are actually like ‘You know what, I am actually making a difference,’ then hopefully they will one day start healing and stop trying to disconnect. I feel like they want to disconnect because they are like, ‘My job is worthless, my life is worthless,’ but when people are empowered through the arts and they see themselves there they are like, ‘I am making a difference, I am the paletero! I bring sweets to the people!’ they will see the value that they are part of the community and not want to disconnect.

I think economic justice will start within the people, within. It is internal. And the goal is in social changes and equality. The next question is, ‘OK, the people are empowered now. How do we get these other people to value the people?’ Then we will need to get other people to value our art like they do the Mona Lisa.

Blanca points to a few key values of Las Imaginistas and the Taller de Permiso project.

1. Placing value in what has been systemically, structurally, and culturally oppressed (a type of narrative reframing)

2. Understanding the collusion of gender inequity as an agent to advance the values of colonization and capitalism

3. Reintegrating agency at the individual and collective level

Numbers one and two focus on the who and the what. Whose voices need to be centered in rebuilding cities for equity? Those who have been systemically, structurally, and culturally oppressed. Women, queer, and nonbinary people especially need to be centered for the ways in which their labor has been undervalued as a strategy to advance the values of capitalism. The existence of our species and our cities requires someone to care for the young and to supervise our households. Yet this labor has gone unpaid for centuries as a way to cement women’s dependence upon men, and to advance the model of the family unit as an alternative to collective community accountability. The future of equity at a city level requires reimagining whose labor is valued and how. Women, queer, and nonbinary people need to be at the front of that conversation.

Number three is something the Imaginistas often hear from participants. They will say things like, “Until this project, no one really asked me what I thought about the city. I never felt like I could imagine what I wanted, because I felt like no one cared.” When people say things like this, I don’t take it to mean that they have never seen a public forum asking them to weigh in on, say, the future of parks in the region, but rather that within those structures they still don’t feel like their opinions really matter.

I can relate. That is why we do the work we do. Traditional avenues for community engagement feel as cold and disconnected as voting in a federal election.

It is easy to feel like participation doesn’t matter, whether in a federal election or in a local forum on parks, because there is no system to respond to the inherent nuance of the individuals who participate. That nuance is what art allows for. It allows structural reflection at the individual level, which is incredibly important when rebalancing power inequity. If we are to create more just cities we need to send strong, clear, structural messages to those who have been systematically oppressed that their voice matters and their input has influence. Art is an important strategy for collecting that information, but until cities begin to integrate and reflect back these voices there will still be a stopgap in this cycle of completion. When Blanca says, “How do we get these other people to value the people … to value our art like they do the Mona Lisa,” what she points to is that programs like Taller de Permiso can make the individual feel valued, but there are limits to how effective that strategy can be in implementing cultural change without the interest of those in power to shift their understandings of whose voices should influence the future of a city and how.

Designing the future of economic justice at a municipal level will not be solved by a forum or the contract engagement of a design firm. It has to be a foundational anchor point within a culture of change that is networked across power differentials. In his book Columbus and Other Cannibals, a critique of the West’s addiction to overconsumption, Jack D. Forbes says, “The ‘cosmology’ or ‘world-view’ of a people is closely related of course, to all of their actions … In short, one must judge cosmology by actions as much as (or more than) by listening to words.”

What is the cosmology or worldview of those in power who say they are working towards economic justice? Is it empty gestures, or do those who have the most at stake feel the impact of their stated intentions? Is there a disconnect between what a city says it wants (to listen to the community) and what its intended audience feels (does the community feel listened to)?

Agency is about those who have been disenfranchised reconnecting with their power and dreams for more just futures. But agency is also about those in power wanting, believing, and taking action to bridge the gap between what cities declare they want and what they actually do. This is perhaps the defining question of the futures of cities, government, and economic justice in the next 10 years as we approach the point of no return in climate change, have increased collective development of a racial consciousness awakening, and work as a nation to redefine our relationship to capitalism. Will we take action to do what we say we want, to live into the values that our cities and nation proclaim, or will those declared values prove to be empty words? The track record of our collective cosmology of those in power for advancing just economic futures is poor, but perhaps with a mixed record of fault. Some highly influential people played strong roles in creating the infrastructure for wholly unjust systems. But the world is waking up to the disconnect between what these systems claim to do (create opportunity for everyone equally) and what they actually do (perpetuate the wealth of the few). Now, with this information, it has yet to be seen how those in power will respond.

Biographies

is a mixed race and mixed Indigenous healer, warrior, and visionary. She is a cofounder of the socially engaged artists collective Las Imaginistas, recipients of the ArtPlace America National Creative Placemaking Award (2018) and A Blade of Grass fellowship (2018). Her work breaks spells of colonial patriarchy by centering the femme and nonbinary gaze and re-integrating the construction of self with the madre tierra. She holds an MFA from Columbia University and a master’s degree in education from Harvard. She is the lead author for the Imaginistas’ forthcoming book on shifting the public imagination using art (Amherst College Press, 2022). When not working with Las Imaginistas, Patiño Houle works on immigrant rights as the Network Weaver of the Rio Grande Valley Equal Voice Network.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.