On the Border between Architecture and Object

The founders of LANZA Atelier discuss the role of scale in their work, which ranges from furniture to buildings.

March 7, 2023

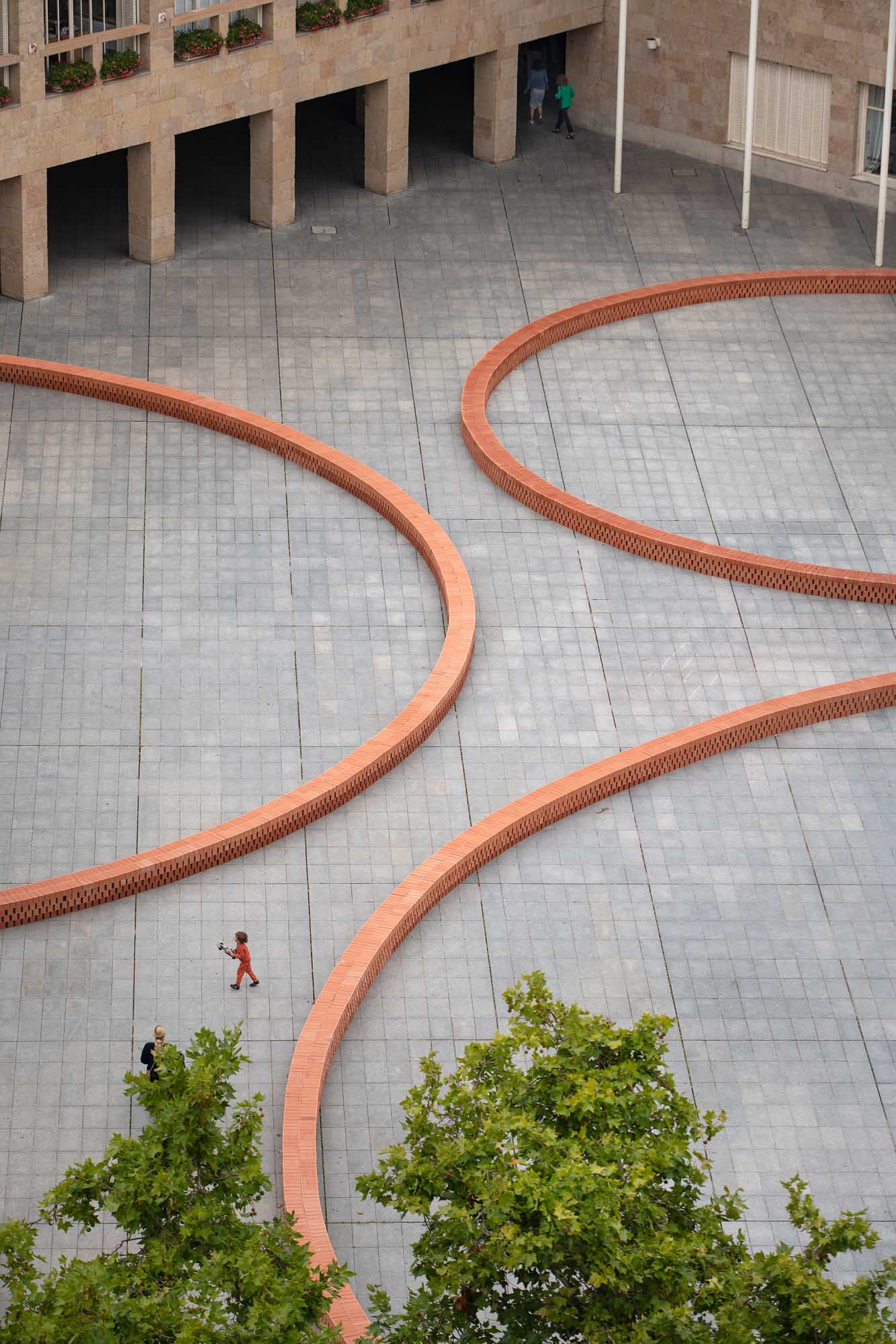

LANZA Atelier's 2021 installation 1973-2021 at the Concéntrico architecture and design festival in Logroño, Spain. Image credit: Josema Cutillas

Since founding LANZA Atelier in 2015, Isabel Abascal and Alessandro Arienzo have received increasingly significant architectural commissions, including public buildings in their home base of Mexico City and a boutique hotel in the city of Guanajuato. But as their practice has grown, they have also nurtured their interest in the design of furniture, jewelry, and other small objects.

The League’s Alicia Botero spoke with Abascal and Arienzo about working across scales.

*

Alicia Botero: How do you think about scale in your practice? Why do you choose to take on projects of different sizes, and how do you think they inform one another, generally speaking?

Alessandro Arienzo: Well, LANZA started with a large-scale project—the public restrooms, which is a repeating module on a seven-kilometer bike path—and afterwards we did a lot of exhibition design.

One of the studio’s philosophies is to not forget what came before, right? The same ideas come back and are explored in another temporal context, another geographical context, another program, for another client.

So we’ve been able to draw connections from the urban infrastructure scale to the exhibition design scale. The size of some of the studio’s projects has grown, but we’ve never let go of the scale of, let’s say, furniture: the scale that’s smaller than the human body.

Isabel Abascal: Yeah. Exhibition design allowed us to experiment with fast projects, very open, with a lot of freedom, testing ideas.

LANZA’s designs for the Passersby exhibition series at Jumex Museum (left) and Art for the Nation exhibition at the Gallery of the National Palace (right), both in Mexico City. Image credits: Laura Cohen, Onnis Luque

I think that through all these years, one thing that’s been very important for LANZA is the need to experiment, and the ways we’ve found to accomplish that.

I noticed this even more during the pandemic. We’ve found ways to experiment not only in the service of clients that commission large projects, or through projects that we’ve won through a contest or whatever, but also through projects we’ve created ourselves—which obviously had to be small-scale so that we could make them happen.

And that’s why there’s been a lot of work on furniture, on objects, but also on things that are neither furniture or not furniture—that are on the border between architecture and object.

Arienzo: I believe that furniture—the small scale—is the ideal vehicle for testing certain mechanisms: surprise, unfolding. In the same way that we use scale models to investigate space and light when designing spaces, we can also use smaller-scale architecture as 1:1 prototypes for studying constructive details, user relations, materiality, and countless other things.

To put it another way: I believe that [artist] Lygia Clark’s pieces made out of aluminum are a clear example of the search for a concept in an object. So how can we find a clear concept in a piece of furniture?

It’s the same story as finding a clear concept when making a space in a house, which has much more complexity and parts and size and space. So in some way, these processes create a synergy, right? They feed off one another.

Abascal: Yes, it’s true that LANZA’s work is very conceptual—well, is trying to be. In the end, each project is a concept, and concepts don’t have a scale. You can explore them through something very small or through something very large.

In the last two years we’ve designed a couple of very large public projects: a school for adults and a cultural center. But I think that, again, our discussions about the architectural strategy are very similar to those we might have when designing an object. At least the initial conceptual discussions—although obviously with many more inputs, such as the urban context.

Botero: Focusing on three projects—Casa Dalia, 1973–2021, and Marimba—can you tell us about the links between them in terms of your design process and the themes they attempt to address?

Top to bottom: 1973–2021 installation at the Concéntrico Festival in Logroño, Spain; Marimba installation for the Re-Source exhibition at Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York; construction photo of Casa Dalia in Mexico State. Image credits: Josema Cutillas, Francis Dzikowski, LANZA Atelier

Abascal: In all three cases we had to work with a complicated space, and try to work with it in a holistic way.

In the case of Marimba, it was designed for Storefront in New York, which is an elongated gallery with a slightly strange shape, like a triangle.

For 1973–2021, our project for the Concéntrico festival, the site is the Plaza del Ayuntamiento in Logroño [Spain], which was designed by Rafael Moneo, and which is triangular and also very arid.

And for Dalia, it’s a steeply sloped piece of land with a lot of trees and large rocks.

So, how to develop a geometric and architectural solution for these complicated settings? I think there’s something in the direct way we’ve always worked in the studio, through hand drawings, initial sketches, and initial models that can be made even of cardboard. And I feel that this allowed us, perhaps, to respond to these three complicated contexts, to these three challenging geometries, in a way that solves everything, right?

Arienzo: With Marimba, it’s maybe helpful to note that it was an exhibition design for different contributing artists in a moment of crisis—a pandemic. And the motivation for the project came from the need for creative fundraising when Storefront couldn’t hold its annual fundraising dinner.

And another goal of the exhibition was to free up space in the basement’s gallery, which over the course of 30 years had filled up with everything from garbage to forgotten wonders. So the exhibit contributors were asked to make work out of this material. And the idea was that the furniture itself was part of the artwork—once a donor buys one of the pieces, they also take a piece of the exhibition design. So there’s no waste, and the exhibition is designed to be domesticated, in a way: To enter a house.

Animation of tables comprising Marimba. Video credit: Francis Dzikowski

Abascal: Yes, the Storefront team had seen other installations we had done with furniture that unfolded and went from something very small to something that took over a space, and that’s why they thought it would be possible to do something for them.

Modulor, a piece of furniture commissioned by Lucia Villers and Alberto Odériz, served as a point of reference for Storefront's curator, José Esparza Chong Cuy. Image credit: Alana Burns

And when we pitched them our idea, they realized that there was a nice link between “buy a table”—when people sponsor a table at the fundraising dinner—and the fact that our project was a continuous surface, but that it was fragmented into more than 40 pieces.

Arienzo: All three projects had very little waste. The Storefront tables went to the donors. In the case of Concéntrico, the festival lasts three days, so part of the deal is that the project can’t take more than three days to assemble and absolutely nothing can be wasted.

Since the space we chose was very large, this was a challenge, and we decided to just stack bricks in circles. The piece was assembled in a day and a half, and after the festival it was disassembled, it disappeared. The bricks were donated through an open public call, and they’ve since been used for different projects around the city.

And in the case of Dalia, the land has a 35 percent slope. In many places it’s illegal to build on that kind of slope. Another very difficult issue is that there are a lot of rocks the size of a person that are embedded in sand—so as we dig, the ground breaks up.

So in our design, all the stones we’re removing are being used to create four or five retaining walls. It’s a question of recycling, right?

I’ve been reading this book about [Swiss architect] Luigi Snozzi. And it’s very good, because it says that architecture has always been very invasive or very violent toward nature. And he’s right. When you see the blades of the machines carving up the mountain, it really hits you.

But that’s one point in time. If the house, in the end, ends up allowing nature to return, the bugs to return, the vegetation to return, you begin to have a symbiotic relationship with nature, and, in the long term, you become part of it. So I think that’s part of the philosophy guiding these projects.

And then we can talk about the fact that these three projects are curvilinear. In the case of Dalia, we had to deal with the slope. If we put the house very low on the site, we would lose a very important view, and if we went to the top of the site, it would be very difficult to climb. So we decided to divide it in half, putting the common spaces halfway up the hill and the bedrooms on a level below.

But the site isn’t clear and right at the middle there are two very large trees. So what did we do? We came up with a curved line that avoids the two trees. And that creates a concept for the whole house. The curved retaining walls are stronger structurally, but the curve itself creates the spatiality.

The rooms are semi-divided, so the whole experience of being in the house is not that you’re going from one room to another—instead, there are slight suggestions that things are expanding, closing, or having different moments.

In the case of the Concéntrico installation, our initial drawings started out as a serpentine shape going around the columns—we wanted to touch the building, we wanted to invade it. But in a very horizontal way, because the columns are so tall that we needed something that would allow you to understand the size of the building, but that would lower the scale to seat level, to the level of rest.

So we ended up making rings to entrap the columns. We went with something more classic, and very simple and graphic.

Abascal: Yes, what Alessandro says about the height of the bench is important, because in the original Moneo plaza there are two or three small benches in the portico. There’s a very old interview with Moneo in which he’s in the plaza and the interviewer asks, “What about this project makes you feel happiest?”—it was a very important project at the time, and it still is today. He says, “What gives me the most satisfaction is that I see this old gentleman who has come to sit on this bench and bask in the afternoon sun.” And you see that there are only, like, three small benches in the whole plaza.

So we said, well, this is such a nice wish from the architect himself—let’s do an intervention that becomes almost like giant benches that a lot of people can sit on.

I believe that each of the design solutions from the projects we’re talking about is infinite, in the sense that they can increase or decrease in scale. In the end, 1973–2021 is a section of some bricks stacked up to the height of the bench, and that could be as short or as long as you want. The same goes for Marimba, which could be as many pieces as you want. Even in Dalia, in the end the wall is something that adapts to the position of the large trees, so that strategy could also be extended.

Botero: These last points are a good transition to another question we had. Furniture design requires very close attention to the scale of the body and its movements in space. We wonder how this work has influenced the way you think about designing buildings.

Arienzo: I think that on one hand, with architecture, we always focus on producing clear and simple spaces—on comfort. This is always really important.

When it comes to furniture, though, I think comfort is lower on the list of priorities. Ergonomics aren’t our main goal. Our main goal is to develop concepts through furniture, period.

Abascal: Above all because there are already a lot of comfortable chairs in the world. So if we make a chair, it’s because we want to make a chair that when you live with it, it awakens something in you and it speaks to you—that you relate with it in an active way, right?

Arienzo: Yeah, like it demands something from you, or it gives something to you. In the case of some of the tables we’ve done—the table clicks into the chair, the chair clicks into the table. And suddenly . . . it’s something you’re not used to, and the moment it happens is quite beautiful.

Or for example, when we made the Steps Table, which was a kind of test of the standard height measurement, we raised the height as the seats went along, but really people were comfortable at any height, independently of the fact that they no longer knew whether they were at a table or not, or if they had to sit higher or lower than they normally would, or if they could fit in the seat, etc.

For me it’s part of the investigation of living with objects, and also of asking what is the life that these objects have in and of themselves?

Abascal: Yes, I feel that anyone, regardless of their background, is open to having a spatial experience. And I think that products that are made at LANZA always unleash a powerful spatial experience.

Botero: When you design houses for clients, do you specify what kind of furniture should go in their spaces?

Abascal: At most, we usually specify some pieces of furniture that are a more integral part of the architecture because they’re fixed or built in. In general, we usually leave some freedom for clients to buy this or that. But sometimes there are moments where the client is faced with a space where it’s as if there’s nothing they can buy that would work there, you know? Sometimes we end up designing some furniture when the clients themselves say, “Well, what about here?” But it’s not like we try to control it completely.

But these kinds of conversations with clients can be interesting. It makes me think about earlier this year, when we did a residency at VDL House II in Los Angeles, which was designed by Richard Neutra and his son Dion. Richard Neutra maintained correspondence with his clients many years after their houses were complete. It was Neutra himself who sent them letter after letter years after. “Are you taking good care of your house?” “How is your house?” “How are you doing in your house?”

So there’s this very intense relationship between the architecture, the person who inhabits it, and the people who designed it. And these relationships evolve over time.

Arienzo: Yeah, this book about Luigi Snozzi that I’m reading talks about a client who at first told him that the house was a failure, that she didn’t like anything about it. How could she have trusted this man? What an outrage! Very diplomatic—but she hates her house. And then, five years later, she says that there’s no house more beautiful.

It’s like, wow, how do you judge a home? How much responsibility does the client have to know how to live in it and fit into it and get rid of childhood or family baggage? A lot of people ask for things in their houses that remind them of their childhood homes.

Abascal: It reminds me of a friend who came to our house the other day. We recently moved to this house, which was an adobe ruin without a roof, and we’ve been renovating it little by little. So she came over—she’s an actress and her father’s a lawyer—and she saw our son playing in the house and said, “Wow! It’s clear that he’ll always have a unique aesthetic sensibility. Imagine, I grew up in a house that looked like a law firm.”

This made me think about the fact that all human beings, from the very beginning, internalize spatial experiences at the level of lighting, at the level of ergonomics, at the level of aesthetics of all kinds, and that this also shapes you as a citizen and as a person. So that’s why public architecture, and the architecture of public space, is also super important, in addition to domestic architecture.

Interview translated from Spanish, edited, and condensed.

Explore

Frida Escobedo, Taller de Arquitectura lecture

Escobedo explores the concepts behind projects in Mexico, the US, and Portugal.

Davidson Rafailidis lecture

Stephanie Davidson and Georg Rafailidis present their work as part of the Emerging Voices lecture series.

New Affiliates: Roof Cuttings

A tour of design installations in New York City's community gardens.