Rethinking form and function for a warming planet

Architects face significant hurdles to taking on climate change, says Atelier Ten's Nico Kienzl—but there are also exciting opportunities.

Within the past year, a number of architecture firms and allied organizations have formally declared a climate emergency and pledged to take action. But what should this action involve, and how likely is it to happen at the scale and speed required to prevent the worst outcomes of global warming? In this interview series, the League presents different perspectives on where architecture currently stands with regard to climate action, where it needs to go, and how it might get there.

How committed are architects to preventing the worst outcomes of global warming, and how much agency do they really have? Nico Kienzl, a director at Atelier Ten, believes that most designers agree that the climate crisis is real, but that structural forces often prevent them from taking the kinds of radical steps required. The League’s Sarah Wesseler spoke with him about the barriers facing the discipline—and the potential for new architectural qualities to emerge as a result of climate action.

Kienzl helped found the New York office of Atelier Ten, an environmental design and building services engineering firm, after earning a master’s degree in building technology at MIT and a doctorate from Harvard’s GSD. His projects have included New York’s first LEED Platinum residential high-rise and Columbia University’s Manhattanville campus, among many others.

*

There have been a number of high-profile statements within the architecture community saying that we’re in a climate emergency. Do you think designers have internalized this sentiment? How do the statements compare with what’s actually happening on the ground?

We are in the midst of a climate crisis. Climate change is caused by human action. Buildings play a significant part in it, and architecture needs to change in response. These are facts most architects I know agree on. But there’s a considerable discrepancy between what people say and believe and how this translates into their work.

The problem emerges when architects win a project and the client shows only limited interest in sustainability. Challenges related to the aesthetic vision for the design, commercial constraints, program and schedule, the management and engagement of the consultant team, and the regulatory environment all take over. As a result, their actions often do not reflect the urgency of their beliefs.

There are several reasons for this. A lot of architects really don’t know where to start or if they have the mandate or the technology to affect significant change. So they often fall back to things like getting a LEED rating, and the regular business of architecture takes over.

This attitude is also reflected within industry institutions. AIA, for example, is supporting Architecture 2030, which, although a good start, I don’t think represents the more radical advocacy we want to see from our professional organizations during a crisis.

That said, there are, of course, architects who are really pushing the envelope on climate change, including firms that do their own research, or are doing research-based projects. But for most firms the client is still king, and if there’s not a strong mandate from the client to do something different, they fall back on the practices they know best.

Who are some of the designers you see pushing on this issue?

In most companies there are some individuals that are trying to push their firm forward. Atelier Ten works with a lot of firms across the country and around the world, and many do interesting, forward-thinking work.

Two firms I personally have worked with recently and I think stand out in this arena are Snøhetta and Studio Gang. Snøhetta’s office in Scandinavia is developing and constructing buildings called Powerhouses that strive to produce more energy than they use over the course of their lifetime. They’ve also been looking at innovative materials and are closely working with the GSD at Harvard. It’s not always easy to implement these ideas on their larger US projects, but there’s a mindset within the firm of pushing themselves and the envelope on sustainability.

Promotional video for a Powerhouse building produced by Norsk Hydro, an aluminum company that has partnered with Snøhetta and others on the project.

Studio Gang’s office is in a similar mindset—they approach their work with a real sense that architects need to do things differently, and this idea informs their designs at a deep and fundamental level. This shows in the way they think about form, technology, materiality, but also in the way they engage with their clients and consultants. Again, I think it comes from a conviction of the urgency of the issues that comes from Jeanne and her firm’s leadership.

Architecture is a service business. We design and build for other people, so we can only go as far we can convince our clients to go. It is, therefore, sometimes hard to see from the outside and acknowledge how hard a firm pushed towards environmental sustainability within a given context. Often the most visionary projects die on the drawing board and the public never sees the hard work that has been produced behind the scenes.

Thankfully, some designers are really demonstrating that we have a role to play in rethinking how things are done. They do their best to educate themselves and their clients.

So you think the commercial model is one of the main factors preventing architects from doing more on climate change. What other barriers do you see?

One is that we don’t have access to the right products, or the right information about products. That’s one place where collective action in the industry could radically change things quickly. We saw this when the USGBC wrote the first LEED credits around low-VOC paints. At the time, there were hardly any low-VOC paints on the market, but after five to ten years, you had options in every product category at zero cost difference.

Transparency is also an issue. When LEED asked for more information about what was actually in the building materials, it caused a significant backlash in the supply industry—it was amazing to see how much they resisted. I find it really sad that architects are now running around saying “LEED is dead” and “There is no value in green building certification,” because this was the propaganda of some of the manufacturers on the supply side. They smeared LEED because they didn’t want to get the same pushback that part of the industry faced on VOCs.

So we should be much more demanding of the supply side. We need to work with manufacturers and figure out creative ways of bringing innovative products and supply chain transparency into projects.

Another barrier is that designers still live in an information vacuum when it comes to how buildings actually work. We do energy models during design, the projects get handed over to clients, and then we seldom hear how the building actually works unless there are real problems. There’s a huge disconnect in the industry because designers are typically not paid for their services after the building is built. And often the people who run the design side of projects are not the same people who are on the operations side.

We all need better data in the design profession for us to understand how buildings actually work, especially more complex, energy-intensive projects. I was just in a meeting about a design for a new lab space, and everybody knew what the tenant agreement said about how much electrical power needed to be provided to the lab. But then you ask, “Okay, but how much electricity does the lab actually use?” and there’s silence around the table. Very few people do these studies, and there needs to be a serious level of rigor to make them meaningful. Then that information needs to be distributed to close the feedback loops we need to optimize future designs.

Have you seen efforts to address this gap that you think are particularly effective or scalable?

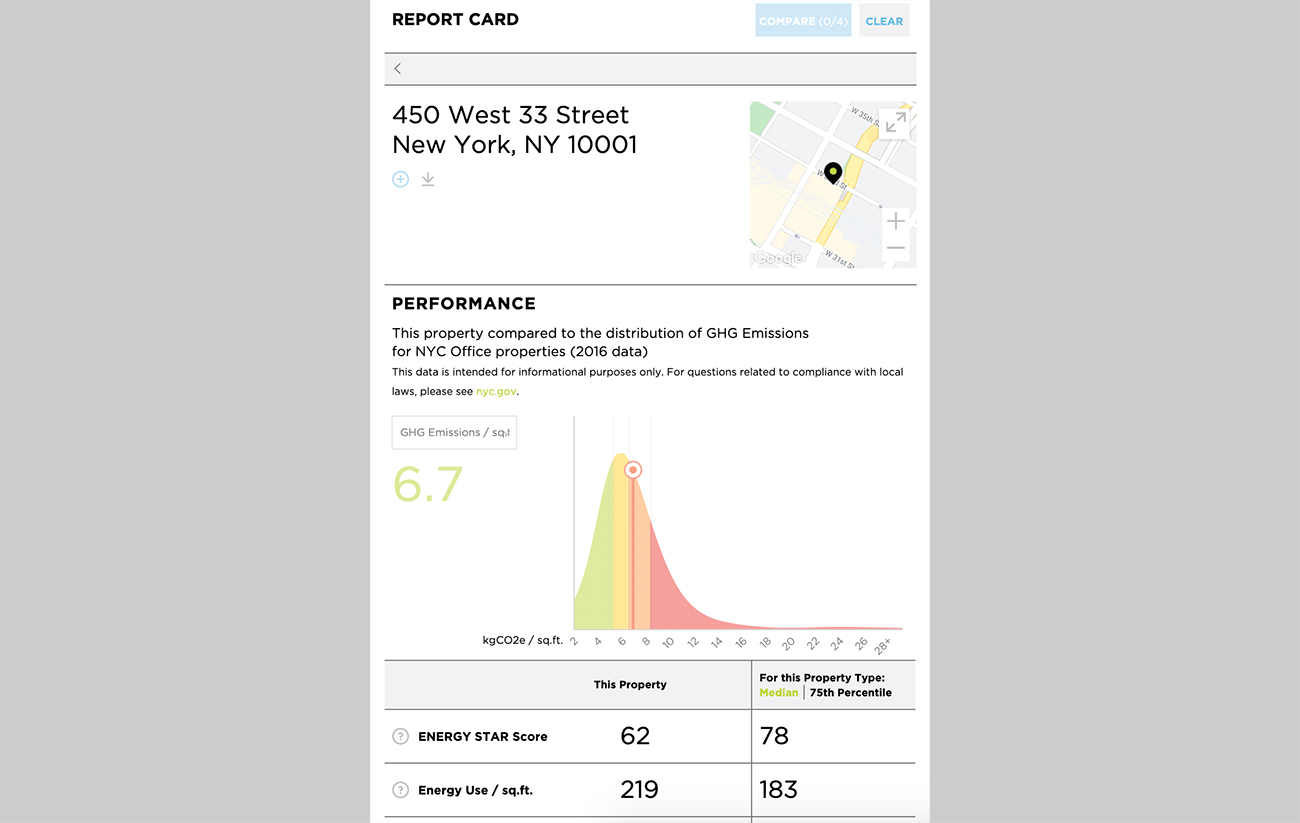

More data collection is starting to happen. The USGBC is working on it; as part of the LEED submission, people are now supposed to upload their real energy data. The City of New York has been collecting data on its existing buildings through Local Law 84.

What’s still missing is a detailed analysis. You can go online and look up the energy use of every building over 25,000 square feet in New York City. But if you don’t understand what tenants and systems are in the building, it’s very hard to contextualize that data. You can’t know if a particular building has really high energy use because it’s a poorly performing building or because it has, for example, three medical practices with radiology equipment. It might be a super-efficient building for what it does. That kind of information is very hard to get hold of.

So data is a barrier. Another barrier is political. Fundamentally, what we need to do is electrify buildings and get significantly more renewable power on the grid, but there is a lot of political and structural resistance in the US about building out this capacity and the distribution systems it requires. There are real hurdles when it comes to things like getting large infrastructure projects permitted. We’re just not seeing that happen fast enough. Overcoming this will require advocacy and political influence to get stronger commitments to renewable power, as Governor Cuomo has recently done in New York.

The discussion about net-zero energy buildings pains me a bit, because a traditional site net-zero energy building strategy will not work in most urban areas. It creates this illusion that we can solve the problem on a building level. That’s why architects are excited about it, but it’s also misguided for most urban projects we see. There are things that architects can do on a building level to improve efficiency to get buildings ready for smart grids and so on. But architects tend to think they need to solve problems on the building level, and electrification cannot be solved on the building level alone. We want dense urban environments, and we will never produce the renewable power we need on a building-by-building level. So we need systems solutions; we need infrastructure supply solutions that are integrated with building-level solutions. We need to push the legislators, the supply side, the utilities, to accelerate this development. And we need to talk to and educate our clients to advocate for that, because they have the real power to push this agenda.

There is obviously a lot of talk about net-zero buildings as a climate solution, so I’m a bit surprised to hear you say it’s a misguided idea. Can you say more about the specific problems of that model?

It really comes down to physics. The amount of solar collection area you need for a regular modern building is about equal to the square footage of the conditioned space. If the building is efficient, you might get down to half the square footage, or even a quarter. But that means that if you’re able to plaster the entire roof with photovoltaics, and it wouldn’t be overshadowed, you could at max make a four-story building net-zero, unless you are in a really mild climate or go to heroics in terms of limiting what users can do in the building.

If you look at an urban context like Manhattan, we have much higher densities. Everything’s taller. And buildings overshadow each other, and then we have a lot of mechanical equipment on our roofs that we need to make the building work. Typically we can’t cover the entire roof with PVs, even if we wanted to.

In an urban context, site net-zero—meaning that a building produces on a net basis all the energy it uses onsite from renewables—is just not an achievable solution. You can say, well, then we should build low density. But low density means we’re using up more land and need more transportation energy to move people around. That’s the unspoken fallacy of a lot of the net-zero energy buildings you see—they sit somewhere where there’s a lot of space to spread the program and renewables out, and everybody drives to them. Once you start looking at their transportation footprint, it becomes really problematic.

I think the solution needs to be really efficient all-electric buildings in relatively dense urban contexts where you can do mass transportation and efficient infrastructure. And then you put the PVs or windmills outside of urban areas, because electrons travel long distances really quickly.

So in your experience, even if you take full advantage of onsite renewables like solar and wind, along with passive strategies, it’s just physically impossible to have a New York-type environment where most buildings are net-zero?

Absolutely, if you take the typical definition of site net-zero. There’s no doubt in my mind. Wind at the urban scale is completely unworkable because you need air flows that you just don’t get in an urban environment. So you’re really only left with solar, and the density is just not there.

Another problem is that PVs typically are dark-colored. But that also means that they absorb a lot of heat, so you actually increase the urban heat island effect by putting them on roofs.

So we’ve talked about barriers. What do you see as the best opportunities for architects to rapidly scale up climate action?

I think the big opportunity lies with existing buildings. There’s a tremendous opening for architects to see climate change as a prompt for designing something much better, much more inspirational, than what we find now. We need to find ways to say, “This is not just a lower-energy building or something that collects stormwater—this is actually a better human experience than what was there before. This has a new quality,” whether it’s through its materiality or the way it brings in daylight or the way it creates value for all stakeholders.

One reason this is important is that we can’t pay for the upgrades that our buildings need through energy savings alone—you can barely pay for anything that way. The City will use regulatory frameworks to move the baseline up, such as with Local Law 97, that establishes a carbon cap for all large buildings. But that alone is not going to inspire anybody to create the fundamental changes in how we think about buildings and the city’s sustainable future.

The existing building stock is the huge majority of the built environment we need to address to tackle climate change in developed countries like the US. Historic buildings of unique significance will have access to funds to spend on improvements, but for most older buildings, such as most class-B office or midcentury residential buildings, energy efficiency savings don’t provide sufficient financial incentive for really significant upgrades.

But if you say, “Hey, this design will create this a really fantastic space, increase the well-being of the occupants, address resilience in new ways, and will allow you to charge more rent and make the building more valuable,” then you can suddenly find funding to do amazing things.

I wonder about that kind of strategy outside of New York or other markets where there’s high demand for class-A space, though. Where I grew up, the building stock is basically generic strip malls and tract housing—that’s the case in so much of the US. I could see some building owners in areas like that thinking they could attract higher-paying tenants or buyers through upgrades, but there’s obviously not enough demand for high-end space to make that a viable option across the board.

You’re absolutely right, and you need different solutions for different places. I also think that there are going to be discussions similar to those happening around resilience, where we start to acknowledge that there are areas where we as a society cannot afford to protect what currently exists in a reasonable way and need to more radically look at replacement with more sustainable models of development.

Ultimately, we all need to finally switch to crisis mode. Climate change is already happening, and we are running rapidly out of time to avoid the worst effects. It falls to us as professionals to be honest with ourselves and our clients about the changes we need to make in how we build and operate our buildings and cities. This will also mean being transparent about where our projects currently fall short and the reasons why, so we can have an open discussion about the changes we need to see in our industry, as well as adjacent industries, such as the utility or transportation sectors.

The scale of change we need will require both market and political transformation that none of us can achieve alone. Collective action is now required. But I am hopeful that what will emerge from this change will be a built environment not of scarcity or austerity, but one of newfound qualities that is richer because it is more in harmony with the natural world. I think this could have some really far-reaching impacts as we transition away from an extractive model of interaction with the natural environment to one that is regenerative and looks at more holistic value systems. It could create new communities that also address questions of social justice and economic equality in new and exciting ways.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

Climate change in the American mind

Anthony Leiserowitz discusses American perceptions about the threat of climate change.

Albert Pope on carbon neutral neighborhoods

Albert Pope of Rice University urges us to “be in panic mode” in response to climate change.

Beneath and beyond big data: Open data

A series of case studies on open data and the process of making data public.