Architects Declare wants to change design paradigms

Michael Pawlyn, one of the founders of Architects Declare, discusses the group's origins and plans for the future.

Within the past year, a number of architecture firms and allied organizations have formally declared a climate emergency and pledged to take action. But what should this action involve, and how likely is it to happen at the scale and speed required to prevent the worst outcomes of global warming? In this interview series, the League presents different perspectives on where architecture currently stands with regard to climate action, where it needs to go, and how it might get there.

Organizations ranging from national governments to professional groups are increasingly embracing climate emergency declarations as a tool for building community around global warming and spurring people to take action. In May, high-profile design firms in the UK made headlines by signing up to Architects Declare, a volunteer-led initiative stating that the world faces a joint emergency of climate change and biodiversity loss and pledging to do something about it. From the initial group of signatories, the 17 winners of the Stirling Prize, the list quickly grew to include hundreds of firms. Today, Architects Declare has chapters around the world and is developing plans to help design and construction professionals reach their climate goals.

One of its organizers is Michael Pawlyn, a biomimicry expert and the founder of Exploration Architecture. The League’s Sarah Wesseler spoke to him in the lead-up to Architects Declare’s working meeting in London in late November.

*

Can you tell me about your background and the founding of Architects Declare?

Sure. I’ll start off by saying that I’m speaking in a personal capacity, because I can’t claim to speak for Architects Declare as a whole; that’s just not the kind of organization that Architects Declare is.

But my background—I worked for Grimshaw for 10 years. I was part of a team that designed the Eden Project, and I got more and more interested in biomimicry as a tool for radically rethinking established ways of doing things, and also pointing to completely new ways of doing things. I got to the point where I wanted to focus all my effort on that, so I left Grimshaw in 2007 and set up Exploration.

There were some other pivotal points as well. After the Eden Project, I went on a five-day intensive course at Schumacher College led by Amory Lovins and Janine Benyus. I learned more in those five days than I had in the previous 15 years of going to conferences and listening to architects talk about how clever they are without ever really getting into proper depth. It really opened my eyes to the potential of biomimicry.

So I set up Exploration with a desire to work in a different way, a more proactive way. Rather than waiting for client to come along and then trying to do the best with the constraints you’re given, I wanted to work in a way that was perhaps closer to a product designer, where you might have an ideal product in mind, you develop it up to a certain point, and then when you’re confident about what it can do, you try and find a client for it. That was the way we worked on projects like the Sahara Forest Project, which we then spun out as a separate company.

There were also commissions where clients came to us because they wanted to push beyond conventional approaches to sustainability. Our Biomimetic Office a good example of that. The client had recently completed a conventional green office—I think it achieved LEED Gold or maybe even Platinum—and was looking to go a step further. So we worked with him and an excellent team to use biomimicry to entirely rethink office design. We were very proud of what we came up with. If it gets built, it should be one of the lowest-energy office buildings in the world, as well as delivering other really substantial resource savings in terms of the structure and the glazing and so on.

Is that getting built?

Well, not yet. I’ll come on to the reasons for that in a minute, as a segue into Architects Declare.

Another fairly typical commission for us was one that we did for a very progressive client in India. They asked us to design a zero-waste, zero-carbon textile factory. We did that; we showed that we can scale all the way to zero carbon, zero waste, and also create a fantastic working environment, with a payback period of around five to six years. So we were rather frustrated when the finance guys told us that that was too long.

One of the things that made me get involved in Architects Declare was a kind of 10-year appraisal of where we’d got to with Exploration. We’d managed to develop some very progressive models—sometimes completely new building types, sometimes existing building types, but completely reimagined. And we were continually being told that the market was not ready for these schemes—ultra-low-energy data centers, low-energy offices, etc. And when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued its report back in October last year, I started thinking, well, this, this is just ridiculous. This is something seriously awry here.

I re-read one of my favorite essays, “Leverage Points” by Donella Meadows, who was one of the greatest systems thinkers of all time. In that essay, she talks about how, because systems are inherently complex, it’s not always obvious where to intervene to bring about the change you want. She found that people very often intervene in completely the wrong places. She draws up a list of the 12 most influential places to intervene in the system in order of priority.

I remember that the first time I read this, I was really quite surprised that some of the things that I thought were influential were way down the list. Rising to the top is changing the mindset or paradigm out of which the system behavior emerges, and the next one down is changing the goals of the system.

This has been part of our thinking on Architects Declare—how can we intervene at those paradigm levels? It’s completely clear that architects can’t solve this problem by creating exemplars and then trying to talk positively about them. That was the biggest mistake I made when I started Exploration—I thought it would be enough to create some exemplar projects, and then we would get this progressively accelerating change that we need. That is not enough, because there are problems at the paradigm level.

The paradigms I’m talking about are our sustainability paradigm, which is flawed, and our economic paradigm, which is still hooked on endless growth. Also, more recently, having read Jeremy Lent’s fantastic book The Patterning Instinct, I’m convinced that the way we view the rest of the living world is flawed. As long as we regard nature as something to be plundered, no amount of well-intentioned initiatives from the construction industry about embodied carbon or circular economy or biophilia or whatever is going to bring about the level of change we need.

So that’s been our thinking, and it’s also the thinking behind a new book I’m working on with Sarah Ichioka. The provisional title is Eight Paradigms for a Planetary Emergency, and each chapter is going to look at a paradigm shift that we need to bring about.

How did how did this line of thought shape Architects Declare at the outset?

Well, initially it led to the idea of getting as many winners of the Stirling Prize as possible to sign up to a declaration. Most of this work was done by an old friend of mine, a brilliant architect called Steve Tompkins. He was recently voted the most influential person in theater—not just in architecture, but in the world of theater. He’s also really passionate about the planetary emergency. So Steve, together with Caroline Cole, who’s a design consultant, did most of the running in getting the Stirling Prize winners signed up.

We imagined that if we got them to make a joint declaration, we could then, with a lot more work, gets other architects signed up, and then we could go to the Royal Institute of British Architects and persuade them to declare an emergency. As it happens, Steve managed to get all 17 UK winners to declare, and then within two days we had another 200 firms signed up. And we’ve now got over 700 in the UK, and 14 or 15 other countries where architects have declared. There are now some other disciplines as well—engineers, structural engineers, mechanical and electrical engineers, and so on. Internationally, there are now over 3,000 firms.

The idea is that it will stay decentralized and that we will share knowledge. For instance, after our gathering in London next week, we can share the lessons learned—what worked, what not so well—with the people that have been key instigators in other countries.

Okay. So with Architects Declare you’re dealing with issues of scale. I think about a lot about the fact that you need the bulk of practitioners to take action—your average building is almost certainly designed by a fairly traditional, conservative architecture firm, or just built by a developer. Reducing carbon emissions from buildings is really a question of volume, and capital-A architecture is a tiny fraction of the built environment.

But since the League has been running the Towards a New Architecture series over the last few months, it’s become very apparent that different design experts have very different opinions about what architects should actually do in terms of climate mitigation—some say solar is problematic, some say hydropower is problematic, some say energy efficiency is problematic, some say insulation is problematic. So if I’m right in assuming that we need as many architects as possible to change their practices as soon as possible, do you think average practitioners have a clear idea of what steps they should take? I personally am very confused.

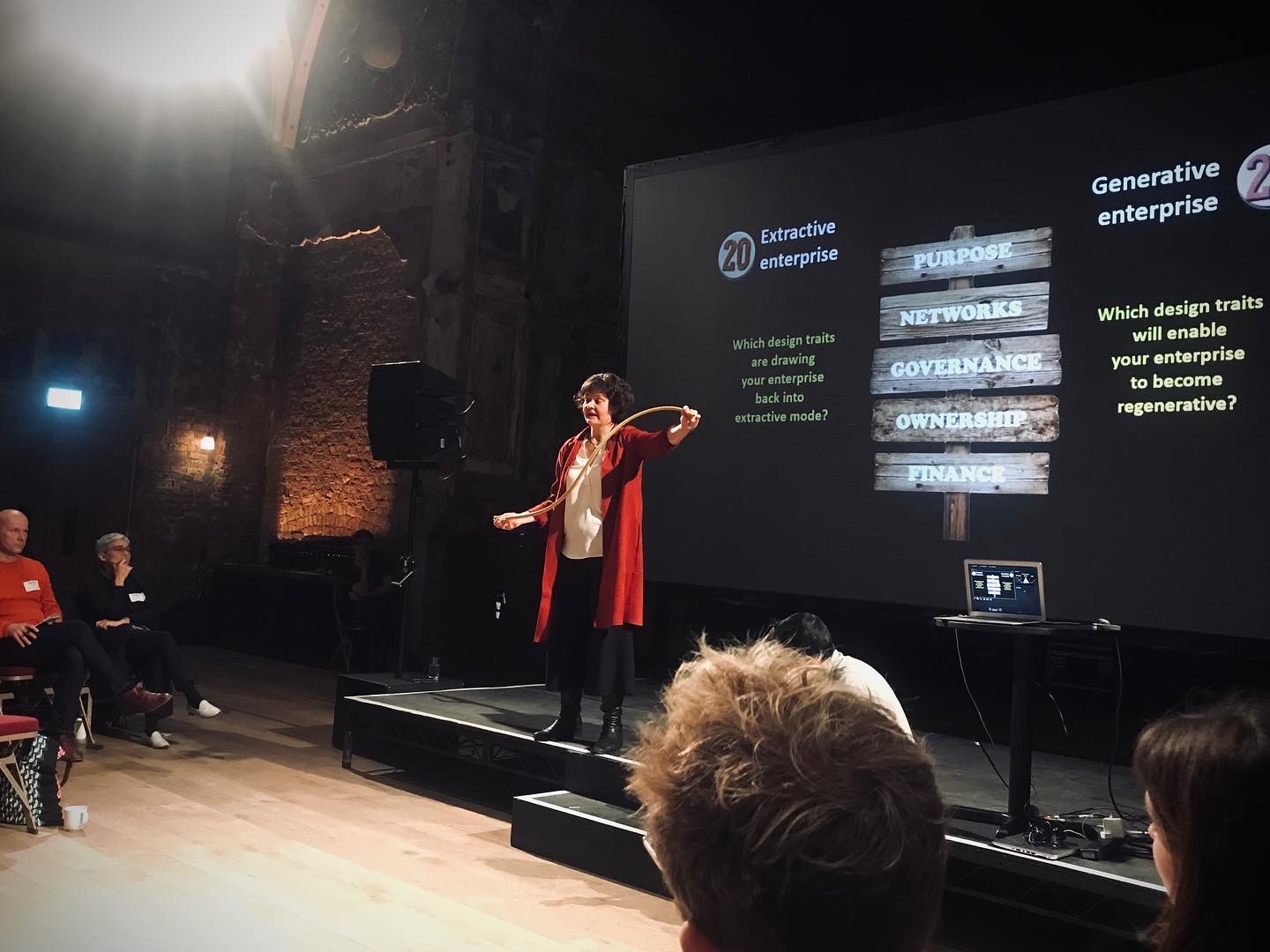

It’s a really important question. For one thing, we are deliberately trying to adopt a culture that is pretty inclusive. We’re deliberately avoiding naming and shaming architects whose actions we may not think are helpful. And at the event that we’re hosting next week, the first gathering of the signatories, we thought it was best not to put any architects on the podium as “the people that know the answer.” We’re not having any architects giving keynotes; we’ve actually got two people from outside the industry. And then we’re going to do quite a bit of work in groups and, as much as possible, get people to arrive at their own conclusions about the actions we need to take. I think convictions tend to be strongest when self-generated rather than imposed.

Both of our keynote speakers address the idea of paradigm shifts. One is Kate Raworth. She wrote Doughnut Economics, which is a book that really rethinks economics—it proposes a model of economics that is consistent with planetary limits.

The other speaker is Jeremy Lent, whose book The Patterning Instinct is one of the most important books I’ve ever read. He shows how, first with the development of dualistic thinking in ancient Greece, and then with the philosophy of Francis Bacon, and then Descartes, humans saw themselves as separate from nature, and increasingly saw nature as something to be conquered. Lent argues very persuasively that we have to re-pattern our thinking if we’re to stand a chance of surviving this century.

Okay, so at this event you’re setting out a big-picture vision, then asking people to work together in groups to figure out how they can operationalize it within their own practices. Is that right?

Yeah, that’s right. And we’re structuring the group discussions around the declaration points on the website—that’s what everyone signed up to. So those are the starting point, and we’re encouraging people to dive into that more.

And importantly, we’re encouraging them to look at how to maximize their own agency as individuals and as companies, but also to be realistic about the limits of that agency and think about where we need other people or organizations to do certain things.

We’re also going to have people vote on which ideas Architects Declare and Construction Declares should be pushing.

How long is this conference?

It’s just a day, so we’re packing quite a lot in. Lots of other stuff also needs to happen.

We’ve been looking into some other ideas—influencing the criteria that awards are judged by; influencing industries and verticals such as the AJ100, which is run by the Architects’ Journal and ranks practices according to their size and profitability. That’s quite a good example of a something that’s encouraging the wrong behavior, so there’s a good case for radically rethinking that.

Okay. So is it fair to say that Architects Declare is trying to change behavior by convening people physically to create solutions together, but also intervening in the mechanisms that produce power and prestige in architecture?

A simple way of describing it in total, using Greta Thunberg-style communication, is that the house is on fire and we’ve got to work out how to help put it out. The longer version of that is that we are in the midst of a climate and biodiversity emergency, the construction industry has contributed to that and is still contributing to it, and it needs to urgently think how it can reverse that situation. And that requires system change to some extent.

So we’re encouraging action on a number of levels. We’re encouraging action within companies, and that’s what the 11-point declaration is largely about. But then some of those declaration points encourage practices to make the case for radical change.

When Donella Meadows talks about how to bring about paradigm shifts, she says something along the lines of, to change paradigms you need to continually point out the shortcomings of the old paradigm while speaking with confidence and assurance from the new paradigm. You also need to put people in positions of influence who understand the new paradigm, and you don’t bother with reactionaries—you focus your effort on the vast majority of people in the middle ground who are willing to be persuaded.

I think that is a pretty good summary of what we need to do. It’s partly about individual action at the company level, and it’s also about, where appropriate, having collective action. We had a steering meeting just today talking about where we need to focus that collective effort, and we’ll discuss that at the event next week. It’s pretty likely that we will get support for collective action on implementing a Green New Deal, and when the new government gets voted in, I think it’s something we’re very likely to push them to implement.

Great. As a last question, although it’s a big one!—if we accept that we have approximately 10 years to drastically reduce emissions, do you think architecture can decide on a course of action, and then take that action, within that period?

My personal view, not Architects Declare’s, is that just working in organizations like Architects Declare won’t be enough. I think it’s going to take really large-scale public protest to make this happen.

Last year I had a meeting with a very senior figure within the British construction industry. I can’t mention his name, but he has advised the British government and sat in quite a lot of rooms with prime ministers. I asked him how we could bring about change, and he said, “The planet is screwed. The only hope now is large-scale nonviolent civil disobedience.”

I was surprised that he was as direct as that, because he’s kind of a small-c conservative; he’s not the kind of person I would have thought of as proposing radical moves. But he’s right. I don’t think change is going to happen at the pace we need to meet the targets set by the IPCC unless we do all this stuff.

Interview condensed and edited.

Explore

Interview: Ants of the Prairie

Joyce Hwang questions gaps of logic in sustainability and pushes architecture to move beyond an anthropocentric view.

Albert Pope on carbon neutral neighborhoods

Albert Pope of Rice University urges us to “be in panic mode” in response to climate change.

Mexico’s Traditional Housing Is Disappearing—and with It, a Way of Life

Mariana Ordóñez Grajales and Onnis Luque are fighting to preserve their country's vernacular architecture.