Light and proportion in the Cistercian monasteries

Naoki Seshimo writes about his exploration of the Cistercian monasteries in southern France through drawing.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Naoki Seshimo received a 2002 award.

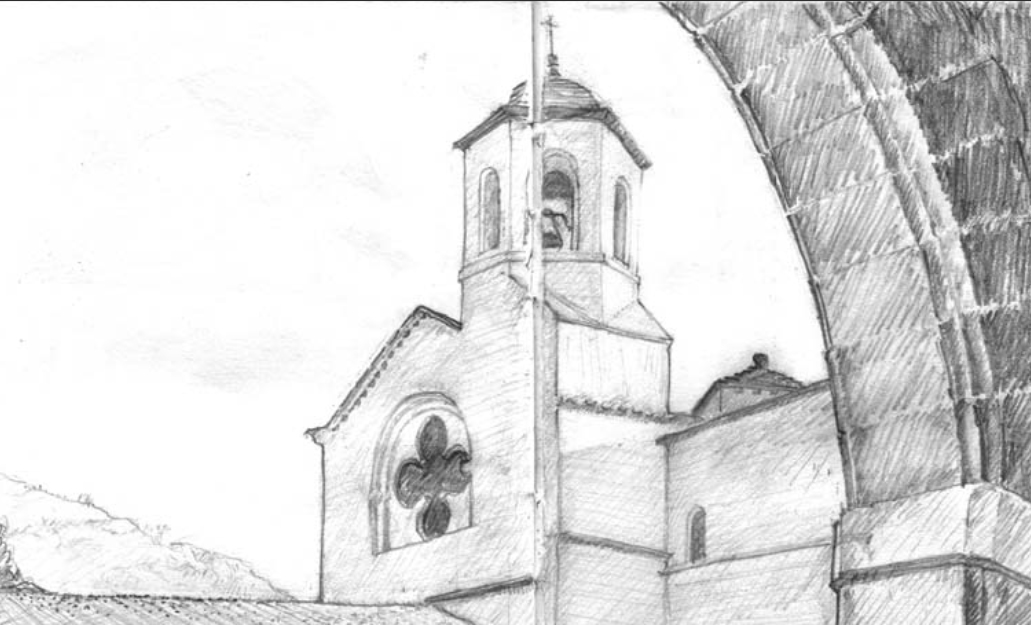

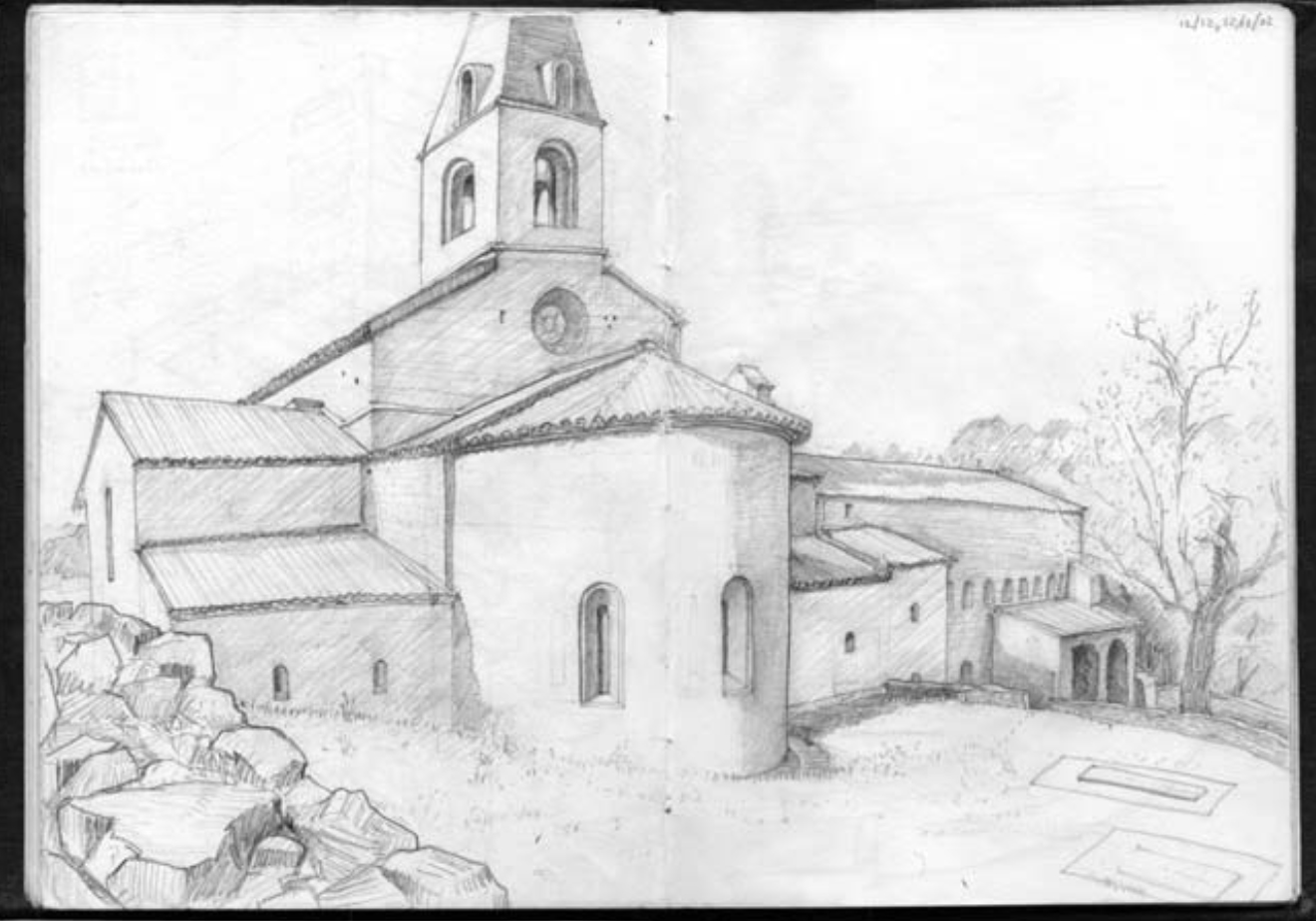

In the fall of 2002, I went on an architectural expedition to the monasteries of southern France. My purpose was to experience light and proportion in these structures firsthand, and to study them through the act of drawing. At Fontenay, Fontroide, Senanque, Silvacane, Le Thoronet, and the priory of Sainte-Marie De La Tourette, I found the monks’ philosophy of simplicity, poverty, and spiritual rigor clearly expressed in architecture.

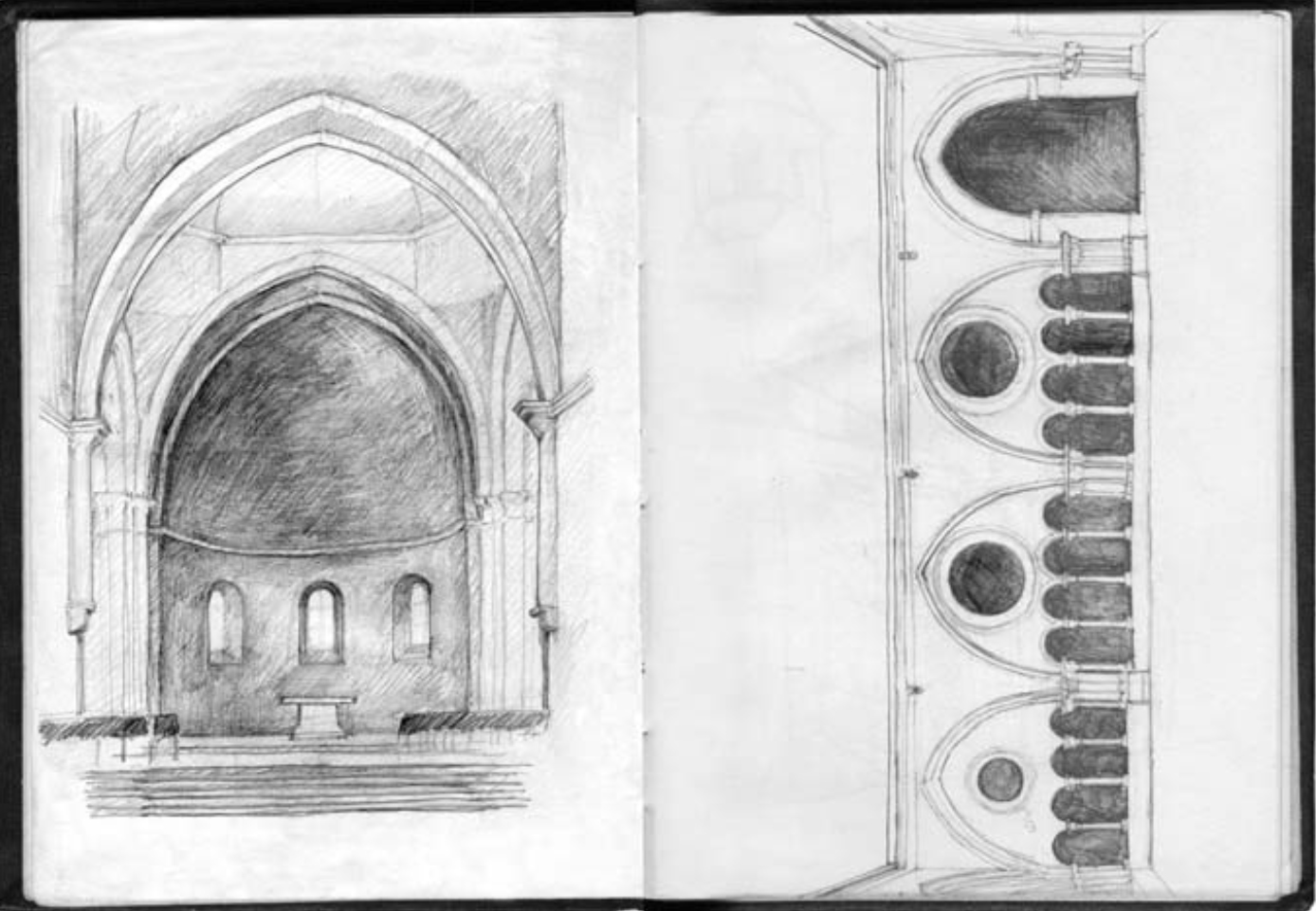

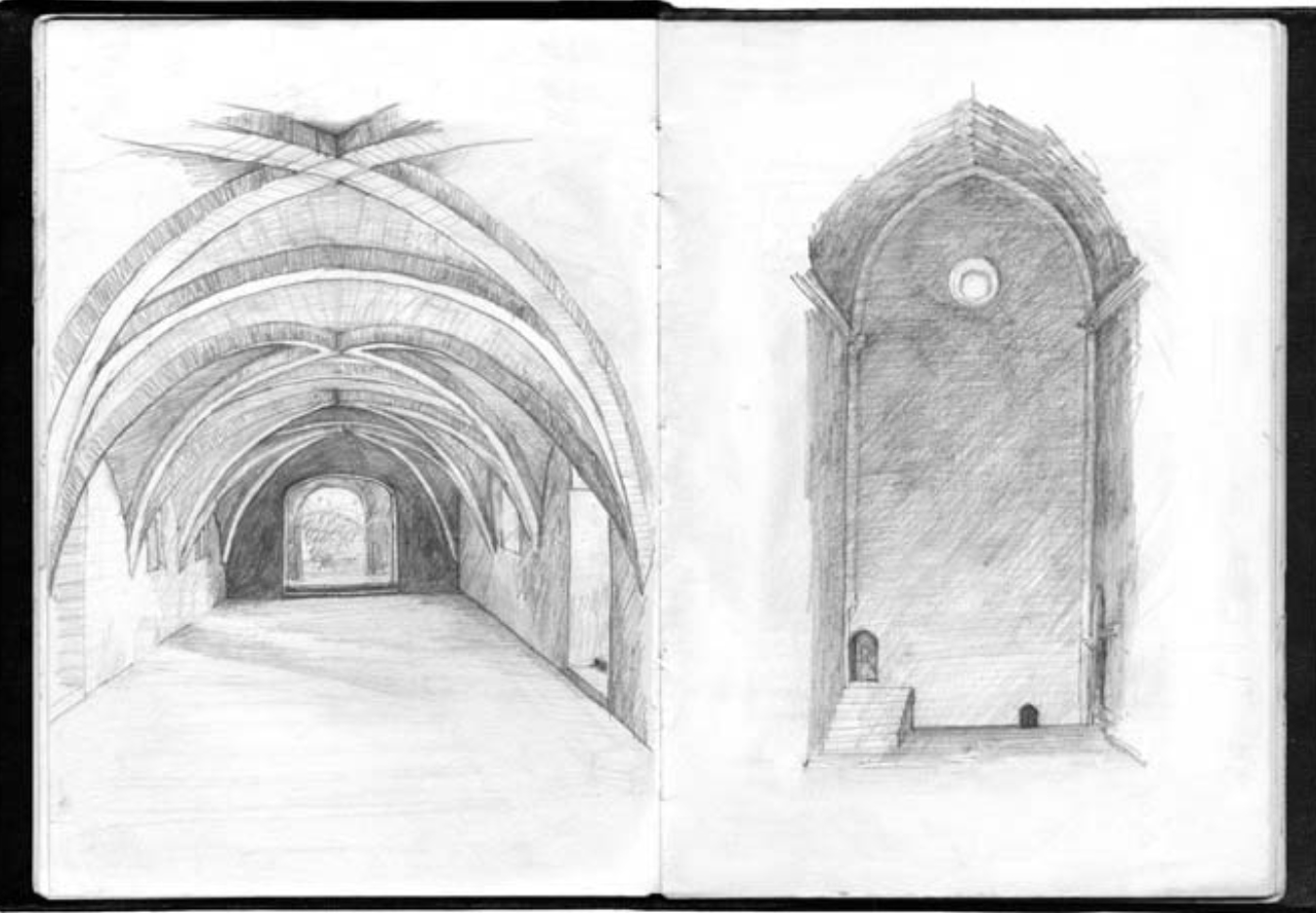

For me, freehand drawing is the best way to study architectural space. With each drawing, I try to record my direct response to the space. This process allows my subconscious to eliminate secondary information, and amplifies the characteristics that construct the place in my memory. At the monasteries, I drew perspectives as I experienced them, observing and recording the quality of space generated by the light and proportion in its own shell.

Unlike typical proportional studies that place vector lines over orthographic projections, this method allowed me to investigate the combination of architecture’s proportional structure in relation to its viewer, light, texture, and spatial depth.

The French philosopher and historian Etienne Gilson once said, “Cistercian architecture forms an integral part of Cistercian spirituality and cannot be separated from it.” Staying at Cistercian monasteries allowed me to gain a better understanding of the concepts that drive their architecture. Striving for purity, the monastic attitude towards life is a rigorous one of work and prayer: “ora et labora,” as St. Bernard of Clairvaux said.

The monks organized their schedules based on the position of the sun, using the ancient Roman calendar that elongates and contracts according to the seasons. The typical floor plan is thus shaped by daily and seasonal rituals. At Senanque and Silvacane, the church’s transept extends and evolves into the dormitory, to accommodate the monks’ life of continuous prayer, which also resulted in a beautiful break of symmetry in its exterior form.

Aside from a few column capitals, the monasteries are completely devoid of ornament. The light patterns created by the sun form the only decoration permitted, embodying the Cistercian association of light with God. With an extreme ratio of large opaque wall surface to minimal aperture, light gains extreme intensity as it pierces the masonry mass of the structural wall. These phenomenological aspects of the structures became even more convincing to me when I took part in the strict schedule and daily rituals of the nuns and priests. As I grew more involved in the daily routine of monastic life, I saw cold and harsh masonry structures transform into sympathetic shelters.

The combination of this light and the orchestration of the spaces and openings creates a silence that fosters the monks’ spiritual growth. The monasteries achieve their grace and strength by reflecting the aspirations of the monks, making its form and proportion seem innate. During the visit, I noticed the strong relationship between the proportion of the building to the concept and the site conditions. It was not an external system or independent mathematical formula merely applied to the project.

In addition, the strength of these spaces could not have been achieved without the monks’ spirituality and strong will. The monks who founded Le Thoronet trekked for days into the mountains of Var in 1140, and at a time when no power tools were available, cleared the land, and worked the stones on site for its construction. The result was a sublime abbey which Le Corbusier described as “the loud speakers of light and shadow”.

To affirm the translation of inspirations from the twelfth century to the twentieth, I visited Le Corbusier’s Dominican priory at La Tourette. Upon receiving the commission from Father Couturier, Le Corbusier was asked him to visit Le Thoronet, an example of “a monastic building dedicated to monastic silence, meditation, and devotion.” Despite obvious differences in construction technologies and methods, La Tourette and earlier Cistercian monasteries share strong conceptual and phenomenological similarities.

With a citadel-like quality similar to that of Le Thoronet, La Tourette rises out of the ground in strong contrast to its rolling rural surroundings. The stark reinforced concrete building is elevated on pillars to sever itself from the ground, symbolizing the priests’ decisive departure from the secular world to enter the priory.

Almost all of the rooms, regardless of function, are organized around a large courtyard with a corridor in a cloistered configuration. This situates them to be open towards the center, underscoring the relationship of individual to community. Throughout the day, the building changes its expression as the shadows of the various volumes in this courtyard and the music-like undulating divisions of the glass mullions display the continuous change of the sun. The church has an enormous spatial depth. Like the abbey church of Fontenay and Le Thoronet, the concrete vessel of La Tourette generates far-reaching acoustical reverberations.

Biographies

traveled to France in 2002. He continues to develop his drawing skills and their application to the design process. Now, he lives in Portugal and works in the office of Alvaro Siza.

Explore

Annabelle Selldorf lecture

A lecture by Annabelle Selldorf, who works nimbly within a wide range of architectural typologies.

The stereotomy of complex surfaces in French Baroque architecture

Hubert Pelletier describes the complex and beautiful structural surfaces of French Baroque architecture. 2009

In conversation: Guy Nordenson and Thomas Phifer

The designers reflect on their history of collaboration.