The stereotomy of complex surfaces in French Baroque architecture

Hubert Pelletier describes the complex and beautiful structural surfaces of French Baroque architecture in three case studies.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Hubert Pelletier received a 2009 award.

The term Baroque supposedly comes from the word used to describe irregular, misshapen pearls. There is indeed a very special beauty in the stretched stones of elliptical domes, in the warped surfaces of spiraling stairs, in the blooming shapes of vaults. Supported by developments in mathematics and geometry, the high renaissance and Baroque periods produced some fascinatingly complex works such as Philibert de l’Orme’s squinches or Hardouin Mansart’s vaults.

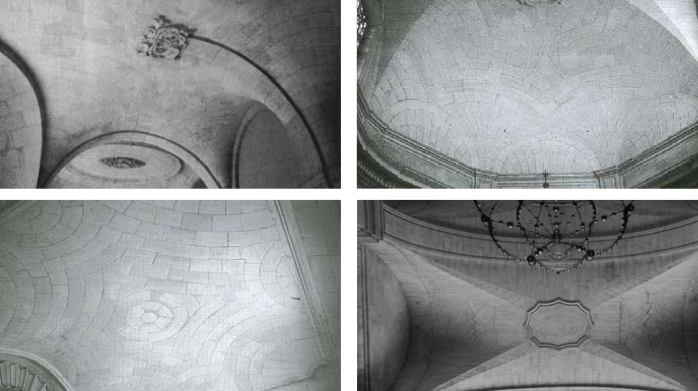

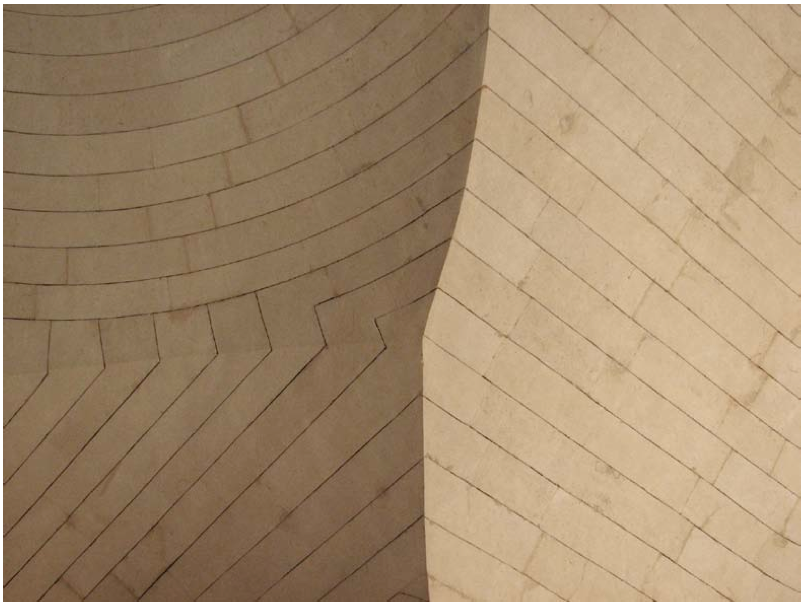

Thinking of the incredible task of building these irregular forms out of individual stones is dazzling. Looking carefully, one’s eye can follow the subtle and intricate web of the joints interfacing the panels, each one having its own unique shape interlocking into the other to create a continuous yet vibrant surface.

Chapel dome from the Anet Castle, France, Philibert de l’Orme, 1545-1552 – Detail of the stones assembly. Credit: Hubert Pelletier.

These joints lines are very interesting; they embody not only geometry, mathematics and construction, but also rhythm, ornament, haptic qualities and expressivity. They are at the same time abstract and sensual. They are the artifacts of the geometric manipulations through which it was possible to tessellate the overall form and determine the contour of the blocks.

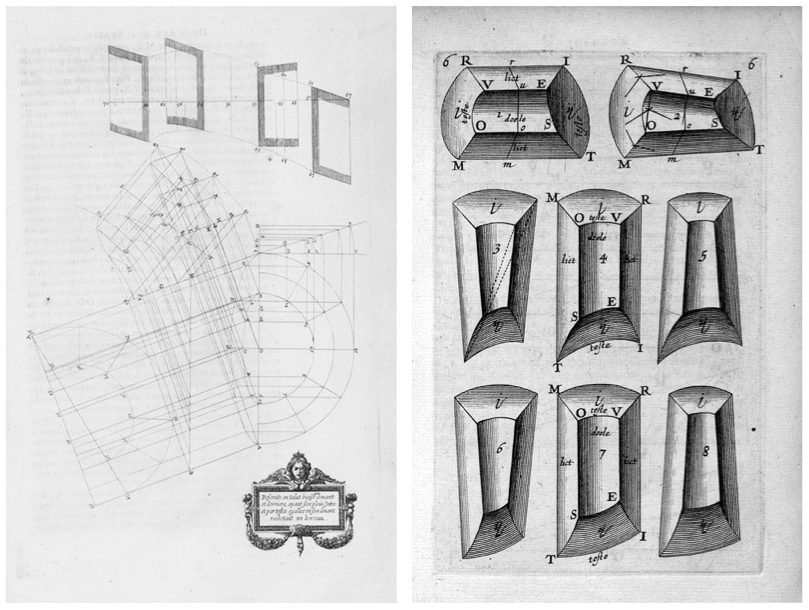

(L) L’Architecture des Voûtes ou l’Art des Traits, François Derand, Sebastien Cramoisi Éditeur, Paris, 1643; (R) Descente en Talus Biaise La Pratique du Trait à Preuve, Girard Desargues, Pierre Deshayes, Paris, 1643.

The hinge that we are experiencing today in geometric description tools (from 2D drawings to the virtual three-dimensional space) is not without parallels with the development of the projection system of the stereotomical drawings (épures) that implemented the realization of some of the complex masterpieces of the Renaissance and Baroque period. Stereotomy was then at the very edge of architecture.

In both Baroque and Contemporary periods, the development of new geometric systems can be regarded as one of the tools allowing architecture to reach new levels of virtuosity and formal complexity.

The underlying idea of this proposal is that studying and understanding more accurately the way the architects of this era linked geometry, formal invention, and construction might inform the contemporary condition. Can the geometric constructions be considered a driving creative force or are they merely a descriptive tool shaping an impulse entirely independant of that tool?

Philibert de L’Orme

In the second phase of my project, I visited buildings by three French architects known for their use of steretomic techniques.

As a character of transition between Renaissance and Baroque, the works of Philibert de L’Orme was one of the focuses of the field trip. His work is crucial to this project because of the direct link between theory and practice in his work. One of the two surviving buildings has elements typically representative of his use of projective geometry to create complex forms. In Lyon, the Hotel Bullioud (1536) features two squinches (trompes) and the difficult “screw of Saint-Gilles” cut of the spiral stair. Also, the Anet Castle (1547-55) where I analyzed the delicate interlaces of the porch’s vault and the chapel’s cupola.

Philibert de l’Orme was born in 1514 in Lyon. His father was a master mason himself and Philibert worked on construction sites from a very young age. At fifteen years old he was already in charge of 300 masons on a construction site in Lyon.

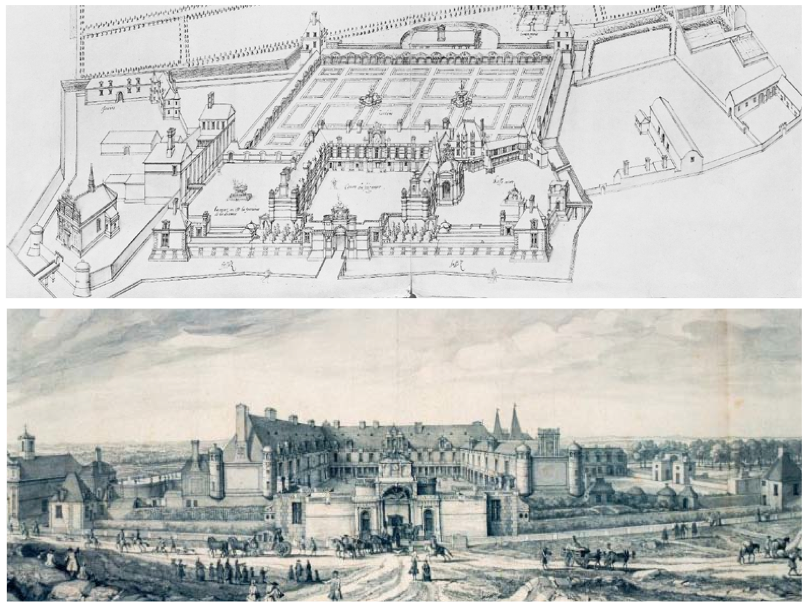

Ten years later, at the peak of his career, De l’Orme caught the attention of King Henry II with the St-Maur Castle (1541-1544) for the Cardinal du Belley. He had been appointed as the Fortifications Inspector of Brittany in 1545 and he would become the King’s Architect in 1548. Henry II started the construction the Anet Castle to house his Mistress, Diane de Poitier.

Originally a large construction organized in three wings around a central courtyard, the castle was partially dismantled after the French revolution in order to sell the stones. With this demolition one of the masterpieces of the French stereotomy disappeared, the famous Anet Squinch. Remaining today are the gate building, the chapel, one wing of the castle itself and the funerary chapel of Diane de Poitier.

Anet Castle, Philibert de l’Orme, 1545-1552, aerial view of existing structures. Credit: Wikipedia Commons.

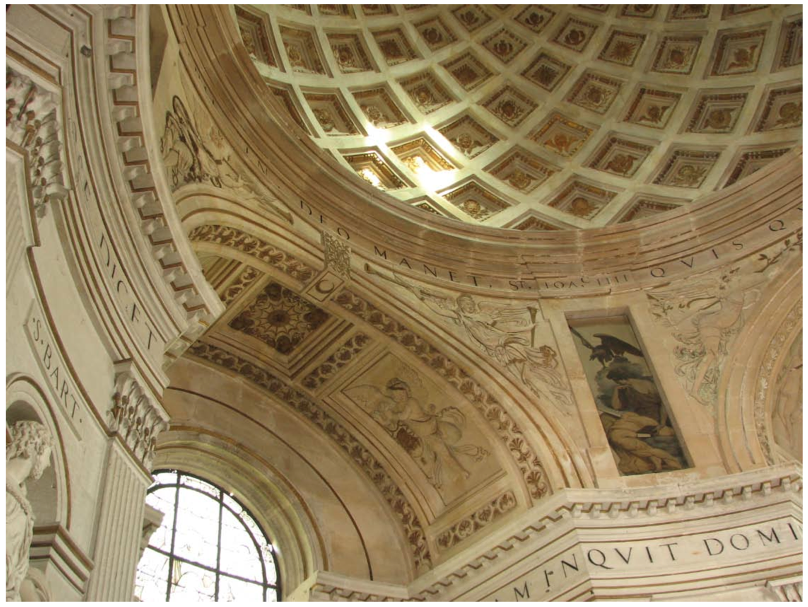

Although they do not involve any special stereotomic techniques, the delicate lacework of the railings are to be noted. De L’Orme uses a vegetal lacework pattern again in the barrel vault of the porch. It is very interesting to note how the construction and ornamentation are synchronized by de l’Orme. Since there is no plaster work or any added stone ornamentation over the load bearing stones, the pattern needs to be engraved directly in the same stones that are composing the structural arch. The panellization of the vault thus has to be thought of at the same time as the ornament to avoid having the joint cutting in the wrong place in the pattern.

Similarly to the barrel vault of the porch, the cupola of the chapel shows how the constructive and ornamental orders are closely intertwined. Each horizontal course is composed of only one bloc that is repeated (upside-down every other repetition). Even with these limited means, the progressive variation in size towards the top creates a rich spiraling effect.

Chapel, dome, stones assembly diagram From Philibert de L’Orme, Philippe Potié, Éditions Parenthèses, Paris 1996.

The diminution in size of the pattern towards the top plays with the perspective and gives the impression of a stretched dome much higher than the half-sphere it is in reality.

François Derand

François Derand (1588-1644) was a Jesuit priest at La Flèche where he learned architecture under Etienne Martellange. He worked on or consulted for various projects, among which are the Orléans Cathedral, the Rennes College and the La Flèche Church. He was called to work on the Saint-Paul Saint-Louis Church in Paris in 1629, a project started by Etienne Martellange.

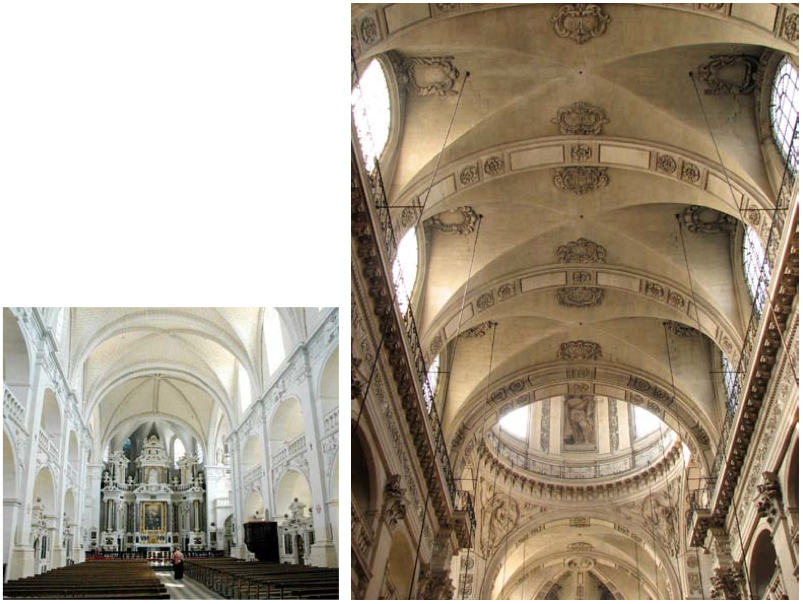

(L) La Flèche Church, Etienne Martellange, 1612; (R) St-Paul St-Louis Church, Francois Derand, 1627 – 1641, vaults covering the nave. Credit: Hubert Pelletier.

It is interesting to note the absence of ribs reinforcing the corners. The gothic technique usually consists in building the structural ribs first and then filling the surface with stones. The infill stones are acting structurally as a diaphragm but not so much taking the compressive load. With stereotomic techniques, the precise cutting of the stones prior to their assembly made it possible to avoid the ribbing and make a uniformly structural vault. Derand took the model for St-Paul St-Louis on the La Flèche church, by Martellange, but eliminated the ribs to make a ‘‘naked vault’’ showing the joints pattern and the smoothness of the surface.

Jules-Hardouin Mansart

Jules-Hardouin Mansart is the nephew of the famous architect François Mansart. He was named First Architect of the King Louis XIV in 1681. Among other works, he was responsible for the Hotel des Invalides in Paris, many buildings at Versailles, and the Meudon, Marly, and Boury-en-Vexin Castles.

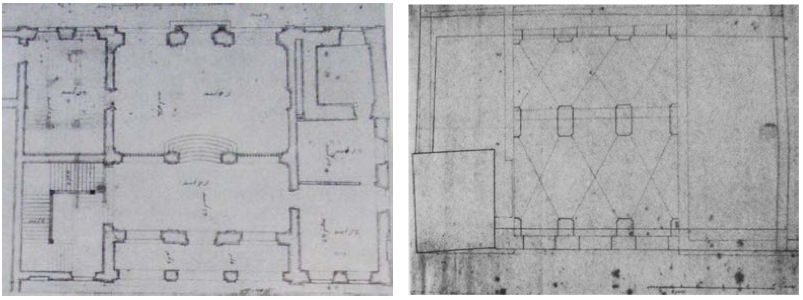

Mansart became involved in the construction of the Arles Town Hall after a long period of indecision with numerous projects accepted only to be cancelled shortly after. The Clock Tower (1558) already existed and was to be kept in the new project for the reconstruction of the Town Hall. In 1665, the city council approved the reconstruction from plans by Jean Sautereau. In 1668, after disagreements, the construction was stopped with the walls about four meters above ground and everything including foundations was subsequently demolished.

Arles Townhall, Jules-Hardouin Mansart, South Facade towards place du marché, 1673 – 1676. Credit: Hubert Pelletier.

In 1673, many architects proposed new plans. The various projects all featured intermediary columns in the center of the space. Plans by Dominique Pileporte were finally approved. The new foundations were finished quickly but the council, learning that Jules-Hardouin Mansart was in a town nearby, sought his advice on the project.

(L) Anonymous, Plan of Ground Floor, Arles Townhall, 17th century; (R) Dominique Pilleporte, Plan of Ground Floor, Arles Townhall, 1673.

Mansart studied the project and made a daring proposal. His plan would completely eliminate intermediary support. With the shallow possible depth of the vault covering the hall, this would be an exceptional structural feat. His plans were finally approved by the council and the construction moved forward.

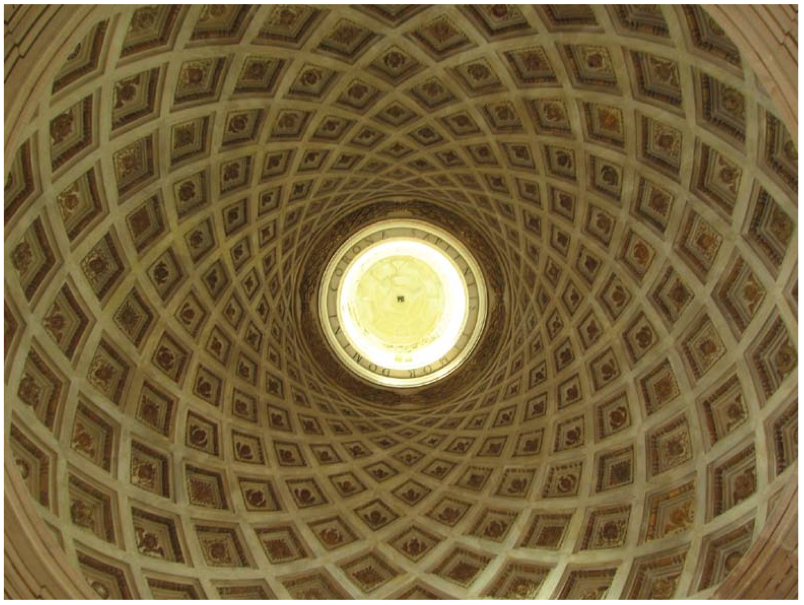

Arles Town Hall, reflected ceiling plan and photographic survey of the vault. Credit: Hubert Pelletier.

The most notable aspect of the vaults is the meticulously planned layout of the stones’ rows. The joints lines echo closely the shape of the vaults, changing directions according to the ridges and breaks of curvature.

Conclusions

After the study of the evolution of his various squinches, we can say that de l’Orme really used the geometric drawings as a mean to create original things he could hardly envision without. As Robin Evans put it in his book on geometry in architecture, ‘‘The shape of the trompe was not merely falicitated by projection drawings, but generated by it.’’

On the other side, François Derand used stereotomy mainly to perfect the construction of a known typology initiated by Etienne Martellange. Where the Martellange vaults at La Flèche were full of visible knuckles and discontinuities, those of Derand in St-Paul St-Louis were smooth and straight, this even after having removed the structural ribs Martellange had previously.

Hardouin-Mansart is a bit of a mixed case. Altough he clearly not had the type of experimental relationship with drawing de l’Orme had, we can feel that the vaults of the Arles Town Hall are the result of the intersections of the various elevations of the hall, creating unexpected arcs and curves where the vaults are intersecting in space.

Biographies

currently based in Quebec City, Canada, Pelletier studied industrial design at the Université de Montréal and Les Ateliers in Paris. He worked for several designers as well as for himself, before continuing his studies in architecture at the Université de Montréal. After graduating, he worked at Daoust Lestage in Montreal from 2006-2008 and narchitects in New York from 2008 to 2009. In 2010 he founded PELLETIER de FONTENAY architects.

Explore

Pelletier de Fontenay lecture

How do you grow a design practice? Pelletier de Fontenay's founders took their cues from a sculptor.

The invariants

The founders of Pelletier de Fontenay seek to strip architecture to its essentials.

League Prize 2016: (im)permanence

Click for slideshow | Exterior view, League Prize 2016: (im)permanence | Photo © David Sundberg/Esto Installation view, League Prize 2016: (im)permanence | Photo © David Sundberg/Esto Installation view, League Prize 2016: (im)permanence | Photo © David Sundberg/Esto …