Inhotim: Contemporary Ruralities

Amanda Coen writes about the role of cultural institutions in rural development by looking at the Inhotim art center in Brumadinho, Brazil.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Amanda Coen received a 2019 award.

When I set out in February 2020 to embark on fieldwork in Brazil, the world was a very different place. COVID was beginning to spread but the worldwide lockdown had not yet ensued. I moved freely through Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, visiting the various museums and parks designed by people such as Roberto Burle Marx and Lina Bo Bardi before embarking on the journey to Inhotim Institute, a contemporary, open-air art center sited in an unexpected location deep in the state of Minas Gerais. The goal of my research was to better understand the social and economic role cultural institutions might play in rural development and how they navigate their relationship with the local community.

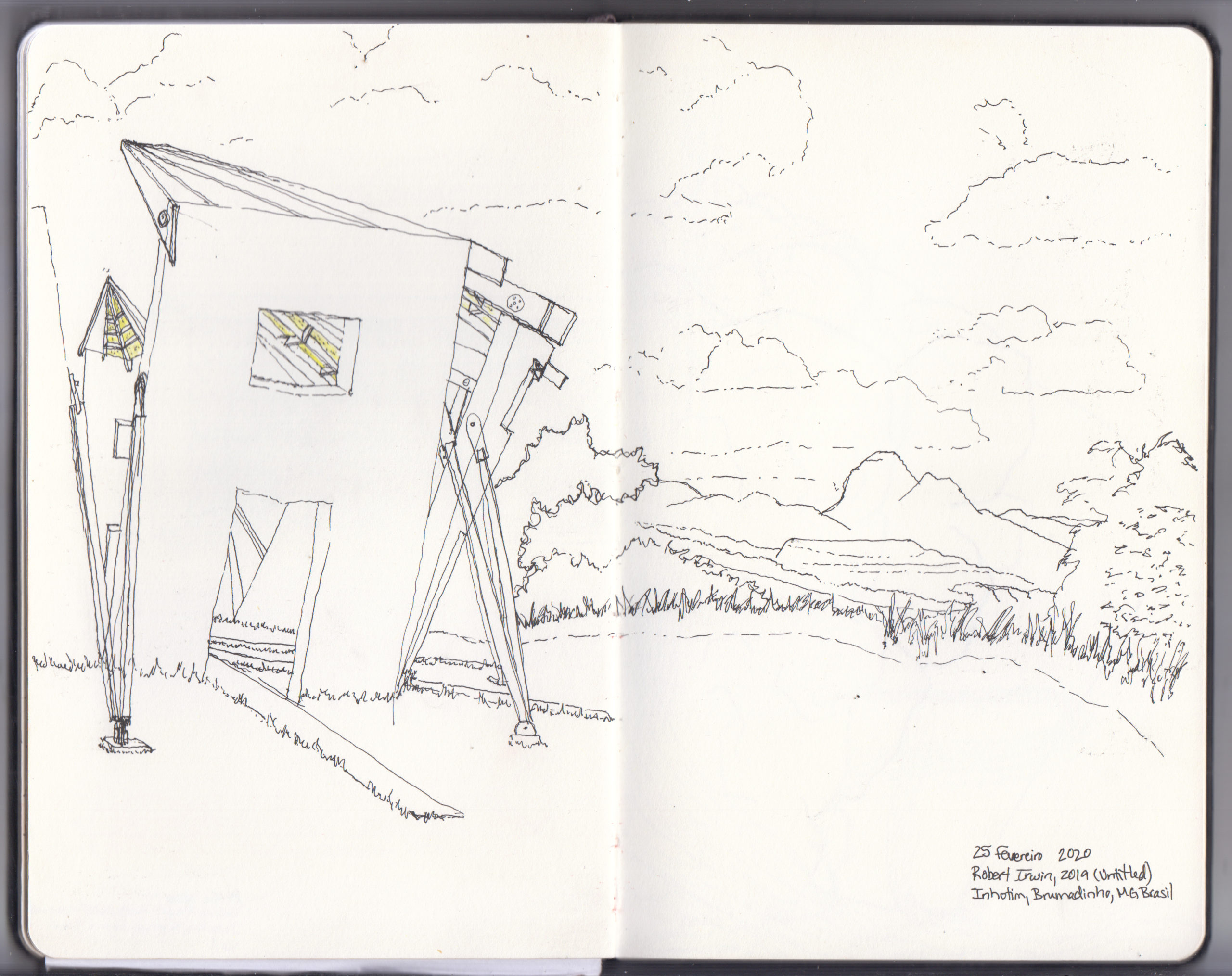

Located in Vale do Paraopeba, Brumadinho sits at the crossroads of the Cerrado (Brazilian Savanna) and the Mata Atlantica (Atlantic Forest) and it’s iron-rich soil is ripe for mining. Credit: Amanda Coen

Contemporary Ruralities

Inhotim serves as a valuable case study for an institution that is defined by and has come to define what I will term contemporary ruralities. These rural realities are often increasingly dominated by resource extraction processes, large scale infrastructural projects, and high-tech agricultural practices that are necessary to fuel growing urban populations. While such industries have existed throughout time, advances in transportation, communication, and digital technologies have increased the intensity and scale at which they operate and shifted ecological, economic and political relations on a global scale. They offer sources of employment to local communities and are dramatically restructuring the rural landscape in the 21st century. Once semi-remote areas are now more connected than ever before.

While these landscapes are often shaped largely by logistics and practicalities, centers such as Inhotim can play a complementary role in rural development, offering alternative sources of employment, points of reflection and critique, and civic and cultural resources to local communities. Moreover, if incorporated into a regional planning process, revenue from the tourism they draw can create opportunities for other small businesses to emerge.

Visit to Corrego de Feijao with Jose Manuel and Vinicius, site of the Vale mining dam disaster in Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, Brazil on March 11, 2020. Credit: Amanda Coen

Inhotim’s Origins

Located in the Ferriferous Quadrilateral, the site of one of the world’s largest iron ore reserves, Inhotim’s existence is deeply intertwined with its surrounding context. The carved mountainsides that envelope the center provide its life blood—wealth tied to the mining industry provided the seed money that fueled a larger dream and continues to provide a large portion of the funding that sustains its existence. In the 1980s, the mining magnate and founder of Inhotim, Bernardo Paz, began to purchase land that once comprised a small village known locally as Inhotim. He constructed a private country residence that served as an escape and place to exhibit his growing Brazilian modern art collection. Roberto Burle Marx visited the property several times and provided informal advice for the layout of the property and gardens. Over the years, Paz’s vision grew as did his acquisition of surrounding properties- he eventually acquired around 2,500 acres. Through a series of conversations with Tunga, one of Brazil’s best-known contemporary artists, Paz was convinced to expand access to his growing collection which included works by living artists that were produced from the late 1960s to the present. In 2006, Inhotim Institute opened its doors to the public for the first time. Today, it welcomes over 350,000 visitors per year and extends across approximately 350 acres dotted with pavilions, artwork, and plant species from around the world.

Inhotim’s somewhat remote location is very much a part of its identity. Within Brazil, the roots of its origin run in parallel to several cultural references that distinguish it from contemporary art centers in other parts of the world. The novelist and diplomat João Guimarães Rosa popularized the idea of the sertão in his best-known work, Grande Sertão: Veredas (Devil to Pay in the Backlands). While referring specifically to the northern region of Minas Gerais, the term more generally encompasses any region far from an urban center and possesses certain cultural undertones. (Atraves, 2nd ed, p 22) “O sertão esta em toda a parte,” (“the hinterlands/backlands are everywhere”) states Rosa in the beginning of his 1956 novel. This socio-ecological synthesis has come to define Inhotim and sets it apart from the surge in modern museums constructed in major Brazilian cities just fifty years prior. The majority were housed in modern buildings designed by notable architects and were largely defined by the urban fabric. Inhotim’s siting outside of a cosmopolitan center, in a region not considered part of the usual cultural circuit, offers a distinct approach. “It is about inventing a world apart, an advanced post that experiments other forms to view a relationship with art, history and nature,” writes Frederico Coelho, an adjunct professor in the Department of Literature at Pontificia Universidade Catolica do Rio de Janeiro, in the publication Futuro Memoria.

Its location also builds upon expanded definitions of national identity and cultural heritage. During Roberto Burle Marx’s time as a counselor to the Conselho Federal de Cultura (Federal Council of Culture) from 1967 to 1971, the landscape designer delivered a series of depositions that called for a cultural shift and revaluation of resources. In her book Depositions: Roberto Burle Marx and Public Landscapes under Dictatorship, Catherine Seavitt Nordenson, ASLA, describes how Burle Marx argued vehemently for the recognition of “notable natural landscapes” as integral to cultural and national patrimony and security, the valuation of contemporary built works alongside historic ones, and the celebration of the biodiversity inherent to Brazil. Though not designed by Burle Marx, Pedro Nehring, Inhotim’s official landscape designer, echoed this line of thinking as he incorporated Paz’s vision for art within the biodiverse crossroads of two important biomes, the Mata Atlântica(Atlantic Rain Forest) and Cerrado (Brazilian Savanna).

A World Apart

As an institution operating in the sertão, Inhotim takes advantage of the physical space that many other institutions can only dream of. However, its location also brings other challenges. For visitors from afar, arriving is no easy task. For me, this involved a plane ride from Sao Paulo to Belo Horizonte, an hour bus ride to the center of Belo Horizonte, and then another 2.5 hours on the local bus winding its way through the twists and turns of the dusty roads accompanied by trucks carrying loads to and from the mines located throughout the state of Minas Gerais before finally arriving to Brumadinho, a city of approximately 40,000 inhabitants.

While Inhotim sits only about two miles from the center of Brumadinho, it feels like a world apart. Márcio Nagô, a local musician who was a guest curator for one of Inhotim’s music festivals, explains, “Inhotim was born big… the city was small. It was scared. People didn’t understand Inhotim. I think with time, education has this function. The education team works with the youth of Brumadinho. It’s another generation that’s going to understand Inhotim. It’s not my generation.” The small city’s treeless streets fill with workers in the early morning and late afternoon as they shuttle to and from the local mines, the main source of employment in the region. Traffic congestions are a normal sight on the two-lane road to enter and leave town. A train line built in the early 1900s to transport gold, iron, and coffee produced throughout the state of Minas Gerais to feed Brazil’s growing, modern cities continues to run through the city. A murky river offers evidence of the mineral riches of the region. While there are several modest Airbnb options in housing typical to the region, most visitors to Inhotim choose to stay in Belo Horizonte. From the center of town, there is little evidence that Inhotim exists.

A stark contrast marks arrival. The red dust of the road clears and palms lean in overhead, luring visitors into an organized oasis of diverse vegetation. The entry point is marked by a pavilion overlooking a pristine, blue lake. In the distance, glimpses of Helio Oiticica’s colorful installation Invenção da Cor, Penetrável Magic Square #5, De luxe sparks curiosity.

While many visitors come for the artwork, the experience extends far beyond. It is almost impossible to cover the grounds in one day. The grounds are defined by sinuous paths, a botanical collection of over 5,000 species, and topographic variation. Moments of contrast and ecological diversity are derived from the closed, jungle-like forests of the Mata Atlântica and the open savannas of the Cerrado in the region. Landscape architecture, architecture, art, and ecology become beautifully intertwined. Navigation is anything but dogmatic. Instead, visitors create their own adventure as they chart the meandering paths that lead from pavilions to forests to clearings to gardens and back again. Getting lost is part of the journey and the space and time that passes between allows for contemplation and a connection back to place.

Twenty-three pavilions designed by Brazilian architects including Arquitetos Associados, Rodrigo Cerviño Lopez/Tacoa Arquitetos, and Rizoma were specifically designed to house the work of distinct living artists. Most are comprised of basic forms. Cubes, cylinders, and domes dot the landscape and offer contrasting relationships between interior and exterior. Some pavilions are open-air, offering framed views that treat architecture, landscape and artwork with equal care. Others take the form of sealed boxes into which visitors descend, creating an all-engrossing world apart that transports them to another realm through sound, light, media projections and disorienting surfaces before restoring their senses to the light of day. Some pavilions are magically discovered within the lush vegetation while others serve as follies that tempt visitors to accept the challenge of a steep climb.

Bridging the Divide

At first glance, the clean lines of the pavilions and meticulously maintained grounds seem a far cry from the outside world. However, the content of much of the artwork provides a tie back to place. The materials and processes used in many of the pieces pose questions related to extractive processes, ecological cycles and land management practices, highlighting the destruction, beauty, and creativity that can result. For instance, in Sonic Pavilion by Doug Aitken (2009) low humming sounds draw visitors up a path that leads into a circular pavilion that emerges from the topography. In the center, a hole is bored 700 feet into the earth where microphones capture the earth’s sounds and tectonic plates shifting. The experience is at once eerie and fantastic as the vibrations of the earth penetrate the body and views from the pavilion allow visitors to see the expansive, mineral rich landscape that surrounds.

Despite this dialogue with the surrounding context, those who are not accustomed to more abstract work sometimes feel they have missed something, making institutions such as Inhotim feel out of reach. Raimunda, the elderly aunt of my Airbnb host, told me about her visit to Inhotim and her impression of the artwork, “Beam Drop Inhotim,” by Chris Burden. “There are those things of iron. Have you seen them? There, in the middle of the forest, embedded in the ground. My brother-in-law from Brazil came and I said, ‘Tell me, what is this artwork saying?’ He said, ‘To me there are some things located there. It must mean something but I don’t know.’” She continued, “There are a lot of things there that people see and don’t understand. But the botanical part there, is very varied.”

Inhotim’s educational initiatives provide a point of entry for many. The institute’s larger educational programming reaches up to 1,500 students from the surrounding schools per week and takes place both on grounds and at the schools in the region. Within Brumadinho, 70 local students per year are selected to attend Inhotim’s classical music program where they come to grounds two times a week for rehearsal. Márcio Nagô explained the impact this had on his son. “Not just the music, but the environment that Inhotim has is contagious. It changed his perspective, his outlook, his way of dressing, of speaking. It changed everything.” Inhotim’s programming has even extended to partnerships with other institutions abroad, bringing students, many of whom had never boarded a plane much less traveled beyond Minas Gerais, to places such as London, Buenos Aires, and New York to meet students their age and participate in cultural programming.

Educational initiatives are not only focused on youth or the individual but also on shifting cultural understandings of the use of space and making the community feel more welcome. This became especially relevant after a series of recent shockwaves hit the area. In 2018, a Yellow Fever outbreak shook the region and caused a huge decline in visitorship. Then, in January 2019, a tailings dam collapsed at the Corrego do Feijao iron ore mine, 5.6 miles east of Brumadinho, releasing nearly five miles of toxic sludge that polluted surrounding waterways and wiped out anything in its path. Over 270 people were killed or went missing, and homes, infrastructure, agricultural land, animals, and ecosystems were devastated. Over a year later, the mining company responsible for the accident races to repair its mistakes. Trucks and temporary work camps populate the landscape. A constant haze of red dust fills the air as work ensues to revitalize the area following the destruction. Roads and bridges are being rebuilt and the search for missing bodies continues. The scale and intensity of the disaster is unfathomable.

The event left a huge scar on the local community and brought a moment of reckoning for the institute as well. Following the mining disaster, Renata Bittencourt was named curatorial director and immediately focused on strengthening community relations. The program “Nosso Inhotim” was initiated in April 2019 to make the local community feel more welcome and give them a sense of ownership. Local artists were invited to co-curate and take part in cultural programming and the entry fee was waived for all citizens of Brumadinho. Janaina Melo, Inhotim’s education director explained that part of the goal was to have the local community incorporate Inhotim into their routines. “They can come here to see an exhibition or take part in an activity but they can also come to go for a walk. Understanding Inhotim as another public space in the City and not as apart that only people who pay the entry have access to. We’re trying to establish this politic.” As a local citizen, Márcio Nagô explained the resulting feeling, “The marvelous thing is that [Inhotim] is ours…Citizens enter for free. There’s a discount for shows. It takes a long time for the population to understand… A lot of people already started coming more frequently but there should be many more.”

Inhotim has been making efforts to make the local community feel more welcome and incorporate Inhotim into a regular part of life. Installations at Inhotim place popular, everyday objects in unexpected settings and engage multiple senses as is evidenced in “Piscina” by Jorge Macchi. On Wednesdays, the pool sees increased use as members of the community come to enjoy the escape on a hot day. Credit: Amanda Coen

Employment provides another key link between the city and institution. As the second largest employer in town after mining, Inhotim employs around 450 people and offers an alternative source of income as well as continuing education opportunities. Workers are offered health insurance, have access to free dental care on-site, and have the option to pay a small monthly fee to receive a full meal in the canteen at lunchtime. A large portion of the workers, between 65 to 112 depending on the year, focus on maintaining the over 85 acres of gardens. Under the landscape design guidance of Pedro Nehring, work is oftentimes carried out without detailed budgets or stacks of drawings, leading to a collaborative process that allows for surprising results.

Intense maintenance work is carried out by a team of skilled gardeners that race to keep up with tropical growth patterns. Material details were carried out by stone workers from Minas Gerais using local materials.Credit: Amanda Coen

Beyond the gardens, there are several other ecological initiatives that blur the boundary between the problematic nature-culture divide and expand the role of contemporary cultural institutions amid shifting rural realities. The extended acreage that is beyond public access leaves flexibility for future expansion and becomes a living laboratory for ecological experimentation. Lucas Sigefredo, the director of the botanical garden explains, “Inhotim is really about developing… new models of occupation of the land. New ways of establishing fruitful and sustainable relations with people, with communities, with entire cities. How to posit arts in this scenario, which is not… well, to go to a museum in a city and to spend like more than three hours inside, it’s really tiring. And many people don’t have that access. Now, having this kind of experience or opportunity for Brazilian tropical people, and people from all over the world in a rural area, in the countryside of Brazil, it’s unique. So you don’t need to get a ticket and fly to New York or London or wherever or even to Sao Paulo or Rio to have a very deep and profound and beautiful, pleasing experience… You can just take your car and drive a few minutes or hours and you’ll be here. And it’s made by Brazilians so it’s very good for people’s self-esteem, for identity… as a way to increase attention.” An in-house team of botanists and engineers conduct botanical research, maintain a seed bank, provide environmental education for staff and the general public, strategize conservation efforts on site and beyond, maintain an expansive greenhouse network where they propagate diverse vegetative material for use onsite and for select projects in the larger community, and work to better understand the larger ecological systems that govern the landscape. Local initiatives, such as Assentamento Pastorinhas, an agroforestry organic production collective of 20 farming families, have benefited from such outreach as their practices evolve.

Looking Forward

Though the institution was forced to close to the public during COVID, it was able to re-open in November 2020. As it continues to look to the future, regional planning efforts could strengthen synergies between Inhotim and Brumadinho and bring increased benefits for both. Márcio Nagô observed, “People come to Inhotim and then they go home. They don’t stay in Brumadinho. There could be a big impact with the quantity of people that come and then leave. It’s a question of management…Inhotim is not a negative thing. The city needs to grow. And take advantage of it; not every city has a resource like Inhotim.” Since Inhotim’s inception in 2006, Brumadinho has seen an increase in revenue from tourism—from near zero percent to 18 percent. However, there is room for development. More options for local accommodation would allow visitors to spend more time in town, bringing revenue that could support other local businesses. Rumors of a passenger train between Belo Horizonte and Brumadinho would ease arrival and could boost regional tourism to other destinations nearby. Garden typologies found on the grounds of Inhotim could begin to seep into the city.

Many of the tensions raised by embedding an institution such as Inhotim (in the local fabric) in the context of Brumadinho result from the worlds and cultures that seem to collide. Like other cultural centers in comparable rural settings, Inhotim addresses questions that might otherwise be overlooked or thought of as superfluous in places where practicalities often reign. It is perhaps this stark contrast that, if navigated with grace / empathy, can have the most impact. Lucas Sigefredo related the importance of Inhotim’s educational programming. “If you’re in a safe place with beautiful interactions and encouragement… you feel you can fly, so you fly. You go further. But if you’ve been told you’re not responsible for your own life, you’re not able to do that, you’re not able to do this, then… why [will you] flourish?” Near but far, the physical space and programming of the center provide an opportunity for the local community to travel to a world apart. In doing so, local perspectives and knowledge can be leveraged to shape holistic, living cultural heritages as articulated through ecological systems, creative expression and built works at all scales that expand beyond the confines of any cultural institution and offer new modes of evolution for the communities of which they are a part.

Explore

A serpentine science

Bryan Maddock writes about the work of Brazilian architect Affonso Eduardo Reidy.

Interview: Estudio Macías Peredo

Salvador Macías Corona and Magui Peredo Arenas draw from their local context to create contemporary buildings with traditional craft practices.

Lina Bo Bardi’s return to Salvador

Angela Starita discusses the architect's (mostly unrealized) plan to restore the historic city center of Salvador, Brazil.