Cheyenne River Reservation, South Dakota

Without Water, There Is No Growth | Cheyenne River

In this interview, conducted on August 10, 2020, Lacy Maher, Assistant Executive director of the Mni Wašté (translated as “good water”) Water Company, a tribally chartered entity of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, speaks to the logistical and bureaucratic challenges of delivering water through an undersized rural pipeline system. She discusses how a recent water moratorium has impacted the growth of housing and economic development, and upgrades the water company is making to increase availability. —Annie Coombs and Zoë Malliaros, The Lakota Nation and the Legacy of American Colonization editors

Annie Coombs and Zoë Malliaros interviewed Lacy Maher in 2020.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Annie Coombs and Zoë Malliaros (AC and ZM): Can you give a brief history of the water shortage on Cheyenne River?

Lacy Maher (LM): In 2005, the old intake along the Cheyenne River was silted in. Our water quality was suffering, and there was a very real chance that there would not be enough water to supply the intake. The Army Corps of Engineers was the primary agency tasked with relocating that intake further towards the Missouri River, and worked with Rural Development [of the Department of Agriculture], IHS [Indian Health Service], DENR [South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources], and Housing Authority here in Cheyenne River.

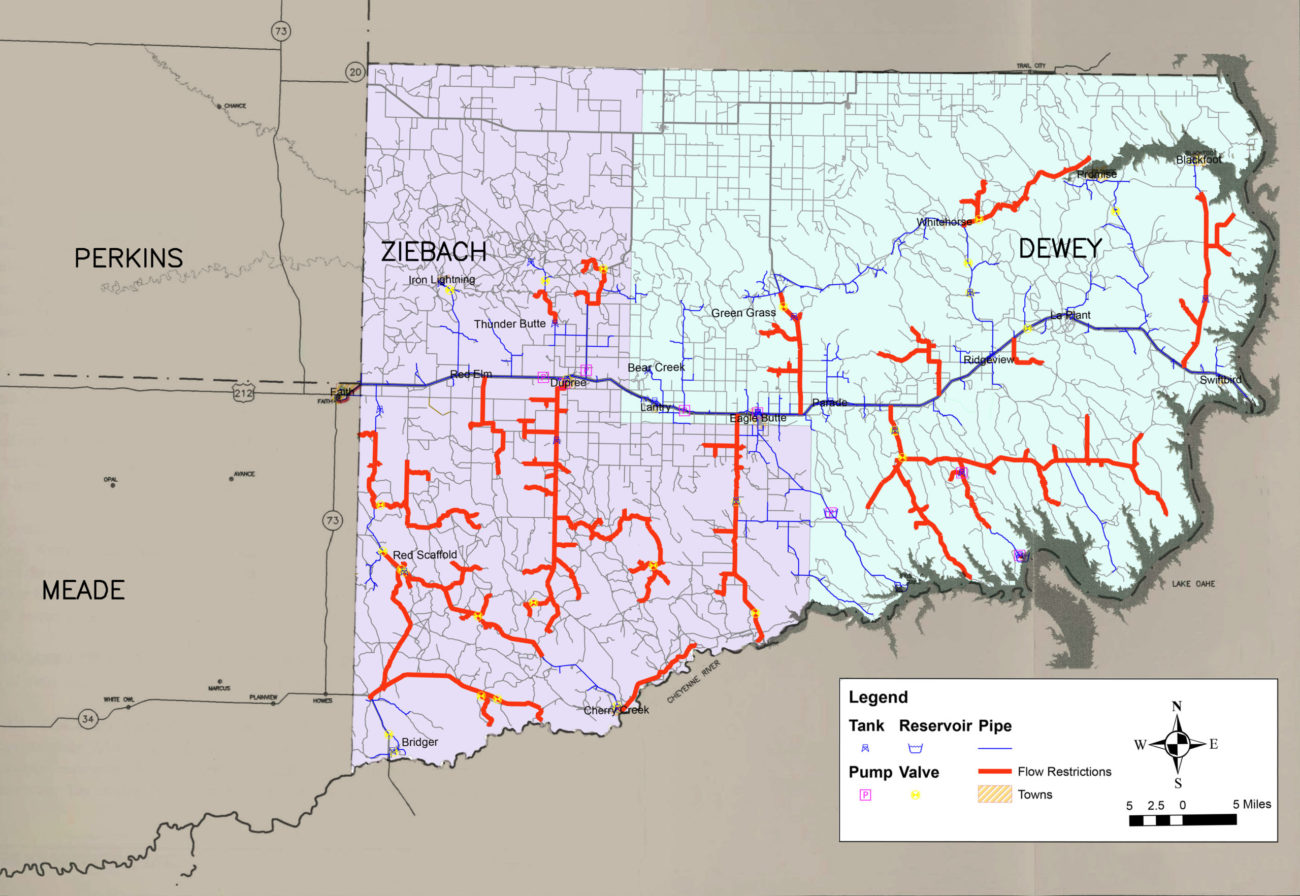

View a map noting the locations of communities and sites mentioned in this interview, along with a discussion of land ownership and governance helpful in understanding this conversation.

Once that was completed, we started the efforts to upgrade the treatment plant near that intake location. The new plant has been completed, and the upgraded water mainline, stretching 23 miles from the plant to Eagle Butte, has been completed. We recently finalized construction on a 2-million-gallon water tower for storage in Eagle Butte. This was all USDA Rural Development funded with a $9.6 million loan and $56.2 million in grant funds.

The next phase that we’re working towards is to upgrade the two mainlines: north along Highway 63 and west along Highway 212. Upgrading the system’s major components was critical. Future work is to upgrade branch and service area lines.

We now can supply all of Eagle Butte’s needs. We are pleased with the progress of the system so far, but only so much water can be pushed through the 1.5 inch service lines that serve the outlying communities without them breaking.1Between 2005 to 2019, no new water connections were allowed across the entire reservation, grossly stunting badly needed development. So that is our next step, to upgrade service lines to the outlying communities.

Our new intake is one of the deepest along the Missouri, and with our new water quality, we hardly add any chemicals.

AC and ZM: Which areas are still unable to get new water lines?

LM: In the communities2“The communities” refers to the 22 rural communities outside of Eagle Butte. While the new water line has reached Eagle Butte, residents of these communities can’t get a new hookup until their branch line sizes are increased., we will do a replacement cap if we can, or if someone is not using or has abandoned one, we will trade out locations. The terrain of the area creates pressure and flow issues, so new services also depend on location. The system itself covers 4,800 square miles, with about 1,500 miles of pipeline circulating the area.

AC and ZM: Are there areas that have never had a water system?

LM: Timber Lake has never been on the rural water system. They just have wells within the community, and have reported having trouble with the wells keeping up. There are blocks within the town with as many as 12 individual wells. Well water is harder to maintain. Corrosion and mineral build up can be an issue. USDA Rural Development recently awarded the project a $9.6 million loan and $17.5 million grant to construct a nearly 40 mile mainline to this area. Indian Health Service is applying $3 million towards the project as well.

Similarly, a project is also in the works to upgrade the mainline along Hwy 212 West, from Eagle Butte to Faith (43 miles.) That’s an additional $38 million dollars. The paperwork has been submitted to DC for that also, but between the two projects, it totals $72 million. It is difficult to fund something of that magnitude. Especially in such a remote area, the dollar spent per person gets to be hard to defend. This westward phase had not been funded yet. The reason I bring it up is that there are remote areas north and south of the projected upgrade that are currently without rural water service or have little to low pressure.

We work with Indian Health Service constantly, and are always working to coordinate mainline upgrades with water storage and branch line upgrades to remote places like Cherry Creek and Swiftbird3Water storage, such as water towers, can help the system in many ways. In a community like Swiftbird, which is located on the east end of the reservation at a low elevation, a water tower would help regulate pressure. In a community at a higher elevation, like Red Scaffold, a tower would help by collecting water.. We are fortunate to have both USDA Rural Development and Indian Health Services. There is no way we could privately fund these projects.

AC and ZM: How many people are waiting to get water?

LM: It’s constant. There was a ten-year period where we were at maximum capacity. People stopped submitting applications, knowing the services were not available. During that time, there were over 1,500 homes and businesses on the waitlist in the areas within the system. Since we’ve released the moratorium4From 2005 to 2019 there was a moratorium on new water taps. Over 900 families were on a waiting list for new housing which could not be built until the moratorium was lifted. The moratorium has been lifted in Eagle Butte and along the pipeline to Eagle Butte. It remains in place everywhere that is not adjacent to the new pipeline. It affected all new construction, including housing and business., we probably have five or six new requests per month and that rate is steadily growing.

Indian Health Service has set up many homes with cisterns due to the inability to get water. When we constructed the new 2MG (million gallon) storage tower [in Eagle Butte], we installed a bulk water fill station making it easier for individuals to haul water to fill those cisterns.

AC and ZM: Was there ever a discussion about taking off some of the livestock taps so that more humans could have access to water?

LM: The human-versus-livestock ratio in our service area is livestock 65 percent and people 35 percent.5Read more in Cheyenne River Surface Ownership. About 50 percent of the land on the reservation is fee patent. Most of this privately owned land is used for ranching; in addition, the tribe leases some of its trust land to ranches. While there are Native American ranches on the reservation, the majority of ranchers are not native. As noted in this conversation, the Mni Wašté Water Company makes more money selling water to ranchers than people, and therefore had not considered disconnecting any taps used for agriculture. Much of our revenue is generated from livestock taps. The water system was established in the 1970s, and it was [originally] designed for livestock. With the livestock, there was a lot of grass that had no water. So the rural water system allowed those [pasture] areas to be utilized [for agriculture] and that is still a foundation of the water system today.

It’s really hard to tell people they can’t have water. Now that the intake has been relocated, the water source isn’t the issue. Fifteen years ago it was, and that conversation was had seriously. Now it’s not. For that we are grateful.

AC and ZM: Can you talk about the impacts from the flooding of the eastern portion of the reservation from the dam?

LM: Without a doubt, it affected the entire area, from the boarding schools to relocating an entire community. It was a huge change, and I guess it’s already generations ago. Time’s gone fast. It would’ve been my great-great-grandparents.

From where I’ve seen, Eagle Butte has really become the hub of the reservation. We’ve got the hospital, the school system, the utilities . . . and those old areas down by the river, they’re just pretty abandoned. The town of La Plant I think at one time was a thriving railroad town far larger than Eagle Butte. They had a lot of livestock. And if you went through it today: Well, there’s a gas station now, and they have put up a school. But it is so empty.

That railroad came through Eagle Butte also. It was before my time. I remember my great aunt, she passed away here in her late 80s. So even 60, 70 years ago, she jumped on the train and went to Minneapolis. She ended up living in Minneapolis her whole life, working, and that was how she got out of here.

AC and ZM: How did the drought add to the water shortage problems?

LM: Because everyone was dependent on the water system, we actually had to limit when people could water lawns and wash cars, things like that, because there was not enough water to serve the demand. Now, we’ve been fortunate the last couple of years to have more rainfall than usual.

At the time of the drought, the new intake wasn’t complete. We were still operating out of the Cheyenne River, and the actual intake itself was at one time within inches of being exposed to air and not even drawing in water. Then with the low water levels above the intake, it was sucking in a lot of silt and mineral, so treating the water was difficult at that time. A lot of boil water notices had to be sent out.

Also at that time, 99 percent of the system was above or at maximum capacity. The old plant could treat 2.2 million gallons per day maximum, and it was working 24/7. Now, the new plant is capable of treating 4 million gallons a day, and it is built to someday manage up to 8.8 million gallons per day.

AC and ZM: What were some of the most telling effects of the water shortage, between the drought and the size of the lines? In terms of people who were without water or projects that couldn’t move forward?

LM: How do you open up a new business? Even today, the Tribe is discussing building a rehab center at the eastern edge of the reservation in Swiftbird. Until we have some water storage there, we can’t ensure that they’re going to have water.

During the middle of the water crisis, the schools and dialysis units were always a huge concern. When the new hospital was constructed, we put a tower there also. Indian Health Service constructed a [water] tower for that facility. There is a hospital and nursing home now to serve the reservation, which is good.

There is a housing development called Badger Park that was finally able to start putting in homes this summer. It’s in progress, and it’s not filled yet, but I know we’ve done some connections out there and it’s going in the right direction. That was a big deal, that project sat waiting on water for nearly 10 years.

The outlying communities of Takini and La Plant have recently constructed gas stations with grocery sales also. These have both been huge assets for their respective areas. People don’t have to drive so far for basic necessities like groceries. That’s something that a person doesn’t really think about—you don’t think about traveling hours to buy food and gas.

AC and ZM: Which next steps for infrastructure and access do you see as being the most important? Where do you hope to see the water lines go?

LM: If we can complete the mainline upgrades, our service lines can then be upgraded. Our goal is to be able to remove flow restrictors on the system so it can serve [our customers’] needs as intended. The system still predominantly runs on flow restrictors. We still have people who, as they’re trying to fill a water truck or cistern, that call in to say, “Is there any way you can get us more pressure? Is there any way?” Well, no, not yet.

Flow Restrictors on Existing System, Cheyenne River 2010. Credit: Banner Consulting Engineers & Architects, with graphic updates for clarity by Annie Coombs and Zoë Malliaros

[In the meantime], people watch out for one another and understand one another. If the neighbor has a feedlot that uses a lot of water during the day, the rest of the neighbors will wash their dishes and laundry during the night. Everyone tries to work together.

There is definitely a need to upsize branch lines, but we had to do all these other pieces to get to that point. It is our hope that the work will eventually allow those outlying communities to develop more. Each of these communities has a clinic, and they have people that rely on those clinics. If there’s a Head Start or school system there, there’s people who rely on that also. And a lot of these communities have an older population, which is a priority. Water is something taken for granted until you don’t have it.

Biographies

is the assistant executive director of the Mni Wašté Water Company. She grew up on the Cheyenne River Reservation and has worked at Mni Wašté since 2014. Previously, she worked at the Cheyenne River Housing Authority.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.