A serpentine science

Bryan Maddock writes about the work of Brazilian architect Affonso Eduardo Reidy.

August 14, 2016

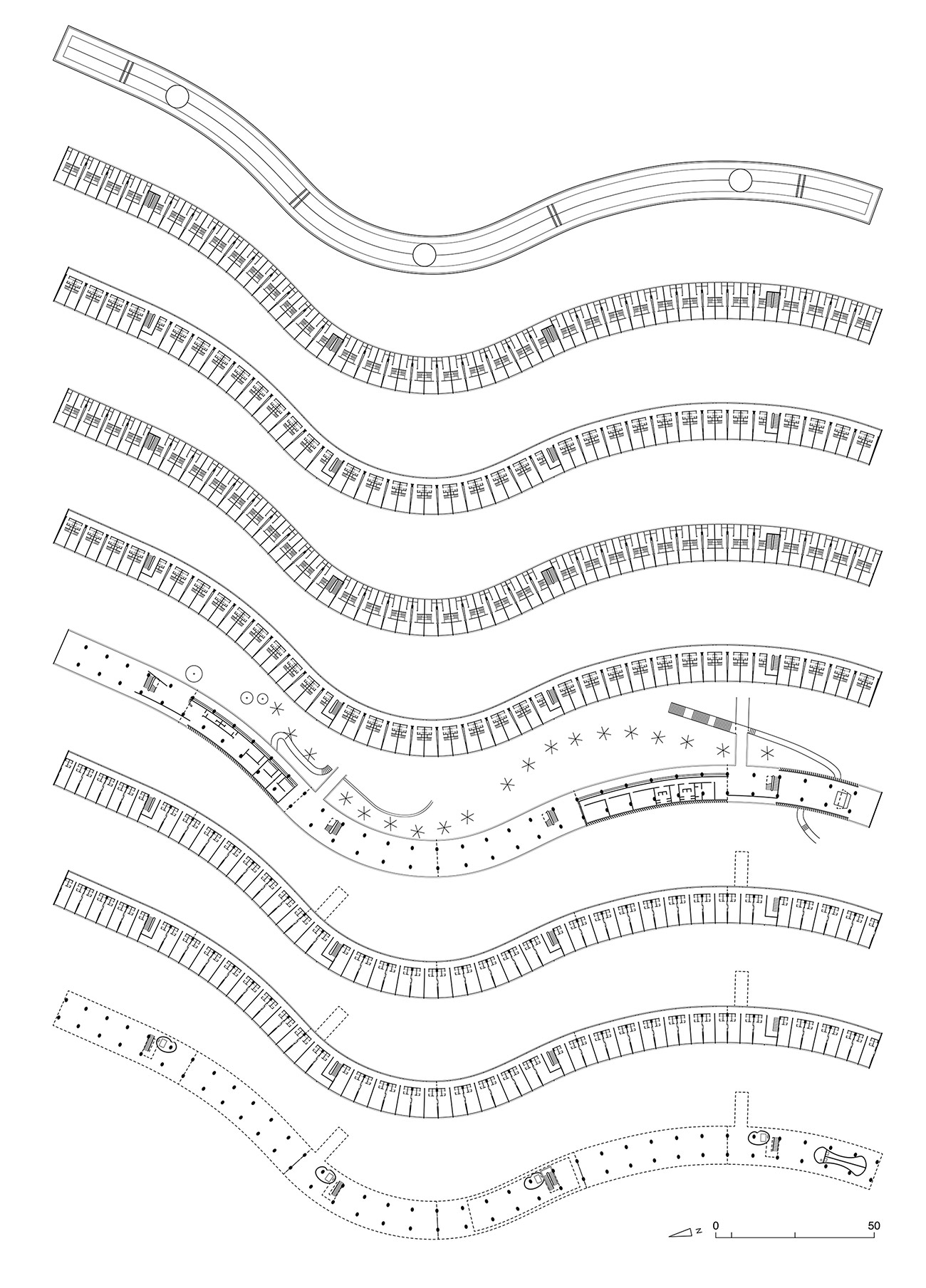

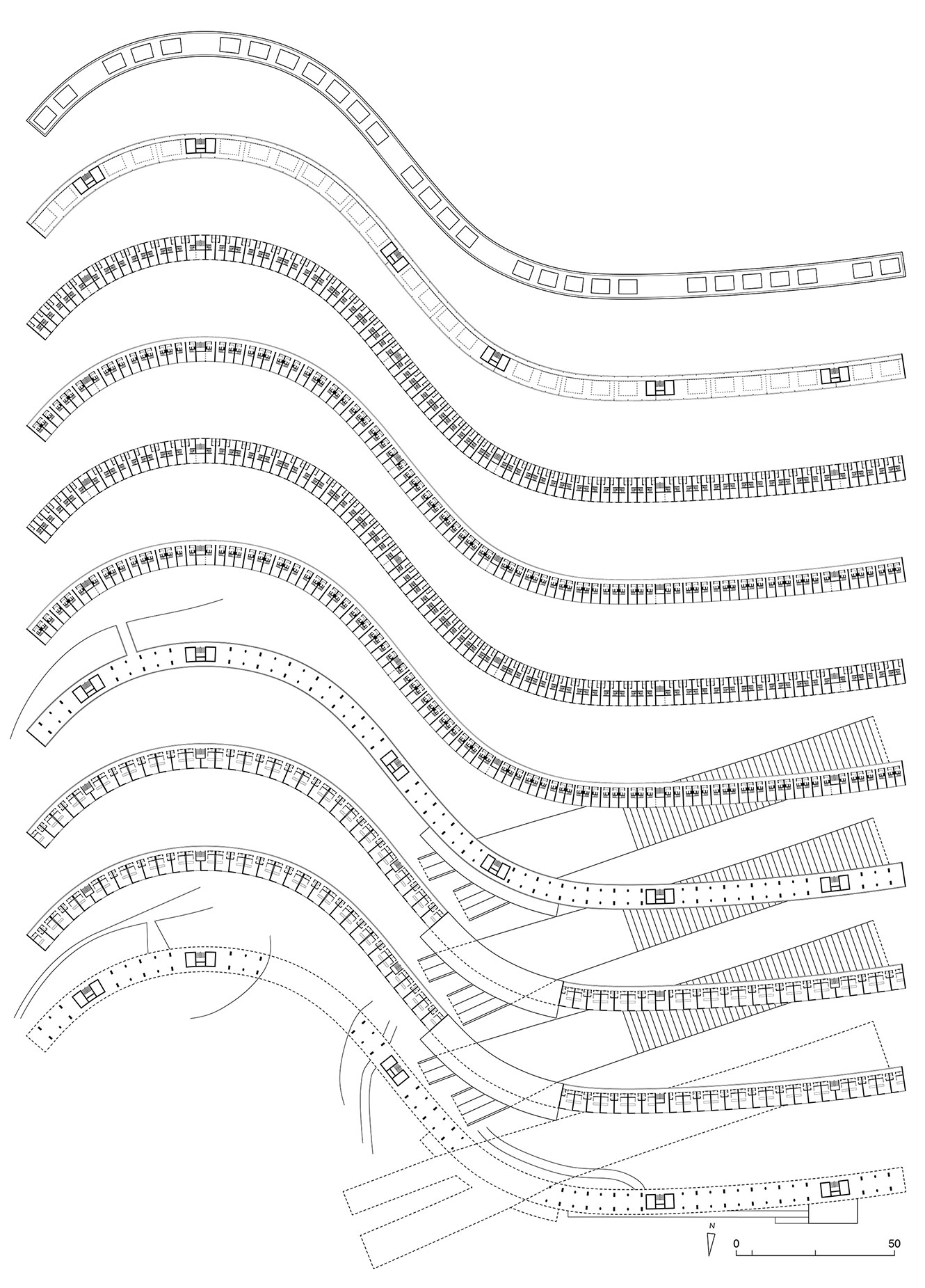

Circulation facades at Affonso Eduardo Reidy's Pedregulho and Gávea housing complexes. Credit: Bryan Maddock

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Bryan Maddock received a 2016 award.

Genealogy, as the long-established method for tracing historic trajectories of architectural movements, requires the faithful to implicitly accept the values assigned to these specific moments in time and space. Those projects and events that find themselves outside of the agreed-upon narrative carry with them a stigmatization that their existence somehow lacked a critical awareness or engagement with the conditions of their epoch. These contradictions, typically labeled as derivative, illegitimate, and accessory, belong to a pervasive category of architectural production that collectively hints at the existence of other ways to speak about architectural histories. Often they are the evidence of an alternative understanding of the conditions of their time.

Framed in this way, Brazilian modernism has commonly been described through generalizations that explain it as a tropical spin-off of the original, and therefore ideal, European model. Operating on the periphery of the world in the eyes of the European modernists, Brazil, along with Cuba, Colombia, Peru, and Argentina, witnessed extreme conditions of urban growth and modernization at the turn of the twentieth century. Seen as a territory ripe for a comprehensive testing of functionalism, industrialization, and standardization, Brazil was transplanted with experimental aspirations desiring to make it an exemplar modernist utopia.

While failure was certainly not an ambition of this importation of ideas, the underlying tensions, created by colonizing attitudes that treated cities in Latin America as subsidiary to Europe, set up a power narrative in which it was understood that modernization in this context would inevitably be deficient in some way. Under these preconditions, modernism in Latin America was doomed to be neither genuine nor have the potential to surpass the European standard. The formation of this binary, of an architecture that either earns praise by embellishing an architectural regionalism or consequently of failure in proving unable to live up to the lofty ideals of modernism, leaves little room for speaking to the original aspirations of modernization as a process that improves the lives of people and cities.

Often producing a “modernism without modernity,” many works that are celebrated for defining the Brazilian style are simultaneously devoid of core social functions toward improving living standards for all. Instead, an alternate reading of projects outside of the accepted modernist narrative, of the deficient works, may provide a closer reading of the regional socioeconomic variables linked to architectural shifts away from strict European models. It is under these terms that the works of Brazilian architect Affonso Eduardo Reidy (1909–1964) reveal an architecture that attempted to balance the regional definition of Brazilian modernism while maintaining a continued concern for social and urban betterment.

Affonso Eduardo Reidy

Working nearly exclusively as a public employee, Affonso Eduardo Reidy’s tragically brief career emphasized the social responsibility of the profession without sacrificing site, culture, or beauty. A core member of what historians call Rio de Janeiro’s Carioca School, alongside Lúcio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer, Jorge Moreira, and the Roberto brothers, Reidy’s forms portray a spirit of optimism and ingenuity partially responsible for the notoriety of Brazilian modernism today. Though his famed body of work includes collaboration on the Ministry of Education and Health (1936), the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro (1954–1960), and the planning of Flamengo Park (1961–1965), it is his ambitious social housing complex Pedregulho (1947–1955) that brought him critical international acclaim.

Understandably well received worldwide, Pedregulho was a resolute masterwork that deployed nearly every modernist tactic, was visibly regional, and did so while also serving as an exemplar social housing prototype for Rio de Janeiro. It was an international poster child for architectural ambitions and therefore is well represented in the genealogical retelling of Brazilian modernism. In contrast, Reidy’s second housing complex, Gávea (1952), would largely be forgotten in the footnotes of history. Regardless of adapting the same typology pioneered in Pedregulho and attempting to improve on every criticism and demand discovered during the process of design, construction, and occupation, Gávea would be labelled as an incomplete project of modernism.

In comparing Affonso Eduardo Reidy’s Pedregulho and Gávea complexes, the shared simultaneity of their construction, siting, programs, and formal strategies highlight the disparity in the manner that they have been portrayed and understood today. In this manner, we can begin to see the two projects as variants of the Brazilian modernist legacy—a comparison that may expose the overlooked socioeconomic terms that evolved an architecture uniquely responding to the conditions of Rio de Janeiro.

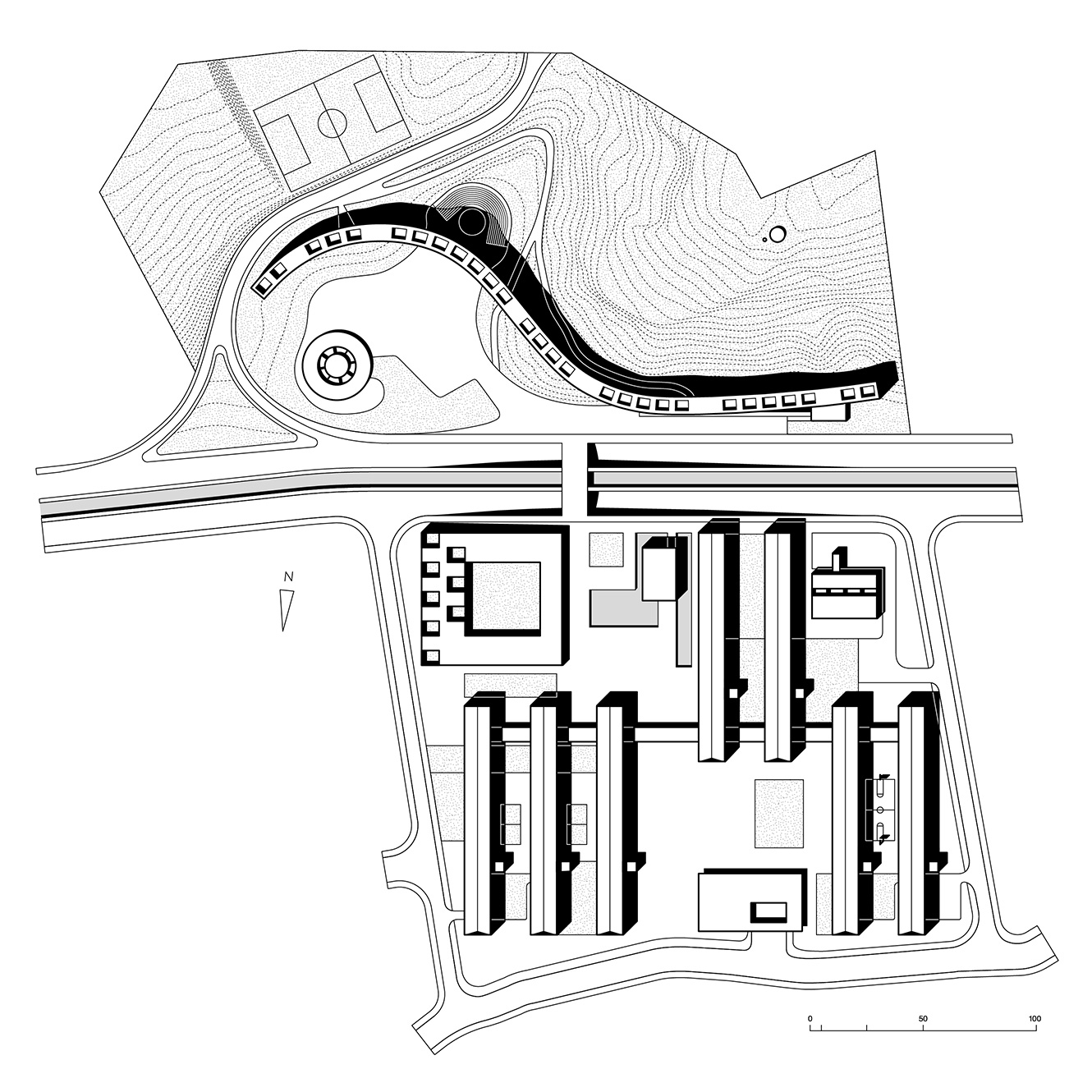

Pedregulho: The "ideal"

Connected in time and spirit to the completion of Rio de Janeiro’s ambitious new highway, Avenida Brasil, the conception of the Pedregulho Housing Development in 1946 marked a new beginning in social housing practices for the city. As a poster child for the state’s newly created Departamento de Habitaçāo Popular (DHP), Pedregulho was a policy defining first effort to establish an upward trajectory for the social housing agenda led by Carmen Portinho, an engineer and Reidy’s wife. Not only pursuing modernization, but also becoming symbolic of taming the challenging mountainous topography and existing informality (tips for which Le Corbusier would first sketch out in his travels in 1929), Pedregulho aggressively replaced established favela communities occupying the same hillside.

Key to the complex was the construction of an entire masterplan including community facilities deemed necessary for the success of self-sufficient neighborhoods. Well represented at the base of the hillside site, a school, gymnasium, pool, market hall, laundromat, health center, nursery, daycare, and club would provide all the desires for a community of this scale. The housing program for a combined 478 units for 1,700 people would be split into three separate building typologies to meet the changing needs of growing families and economic conditions: a serpentine block of 272 units (Block A), walk-up bars of 28 units (Blocks B1 and B2), and a tower slab of 150 units (Block C).

Formally radical yet definitively manifesting Le Corbusier’s sketches, Pedregulho’s most emblematic element of the composition, the sinuous Block A, would become a typology known by the locals as minhocāo, or big earthworm. Stretching 260 meters, Block A is a building that seems to be extracted straight from the topographic contours that it climbs. Tenants of the block enter into an open-air intermediary floor via a pair of bridges reaching out from the top of the hillside. This central open-air void is a social space for community gathering and interaction, while also tactically splitting the building into separate manageable walk-up and walk-down units, therefore eliminating the need for elevators. At 50 meters above the floor of the city, the working class was elevated both physically and symbolically by its new housing and was provided dramatic panoramic views of the city that its daily work helped grow. It was hailed as a social triumph and revelatory moment of the possibilities of an architecture that can address social concerns in a singular elegant and tactical move.

Though the Block C tower, along with the nursery, daycare, and club, would not be constructed in the end, the overall complex was completed without many architectural compromises, which inevitably resulted in much criticism regarding the efficiency of its effort. The complexity, high costs, and construction delays of the signature Block A building would result in it being built as the last structure in a complex that doesn’t function without it. Phased as a series of six sections starting in 1950, Block A would not be fully occupied until the early 1960s—10 years after its construction had started. Arriving just in time for its completion, Le Corbusier proclaimed during his final visit to Rio in 1962, “I have never had the opportunity to undertake a work as complete as this one that Brazilians have achieved with Pedregulho.”

Gávea: The "deficient"

Feeling the ramifications of public criticism of the ambitiously luxurious conception of Pedregulho, the criteria with which further public housing would be constructed faced intense scrutiny. It is within this context that the second of the DHP’s neighborhood unit housing projects, the Conjunto Residencial Marquês de São Vicente, known as Gávea, would begin simultaneous development in 1952. Sited on the opposite side of the city, Gávea was also a mechanism of slum clearance in a district praised for having ideal conditions, visibility to the beach, and increasing land values. Like Pedregulho, this complex would be a replacement for the displaced local community, add mixed-use programs to the region, and attempt to use architecture to blur the class discrepancies between adjacent wealthy and low-income residents.

With a greater housing program of 748 units (compared to Pedregulho’s 478), Gávea was planned to include the same social programs, but strategically swapped the pool complex and club for a chapel and theater, as requested by the original residents of the area. Already facing a compromised site due to it being split by a large vehicular avenue, Gávea would encounter urban problems not felt by Pedregulho. To avoid this issue, Reidy would sink the roadways and provide pedestrian bridges for residents to navigate the divide between the social facilities and the large public esplanade at the base of Block A. In the end, none of the planned services across the avenue would ever be constructed, alleviating the need for infrastructural gymnastics.

Instead, Gávea’s Block A would be built without any semblance of the neighborhood unit (complex) concept. Architecturally, Block A continues the minhocāo typology, but unlike Pedregulho, where the bar situates itself halfway up the hillside, the curve at Gávea instead follows the base contour of its hill and frames a small existing lake. As these projects were meant to be prototypes to be replicated, the malleable nature of their design was implicit in their conception. Gávea would also be reworked through a combination of cost-driven modifications that set it apart from the construction at Pedregulho. In accordance to the public outcry of the cost, utility, and construction time of these public projects, Gávea adjusted its ambitions to meet both the economic demands of the government and feedback from the residents themselves.

A final compromise to its design, and understandably the most controversial, was the mutilation of the block by the Lagoa-Barra expressway in 1982. This aggressive plan led by the city’s Department of Urbanism, now operating under a military regime, ignored the ideological importance of Reidy’s architectural work and accomplished their task for a new highway by carving away 20 units from the center of the building. Unlike a proposed plan to actually split the entire bar in two, the road instead became a covered tunnel as it passed through a newly reinforced structural opening in the project. While accomplishing this infrastructural challenge, the resulting compromise did not account for the increases in noise and physical tremoring of the building caused by intense and continuous traffic. Though this change was done long after Reidy’s death and Portinho’s retirement from the DHP, the lasting legacy of such destructive acts on the project make legible a governmental ambivalence to its once-lofty ideals.

This successive list of compromises has garnered Gávea a reputation as an adulterated attempt to repeat the architectural success of Pedregulho, while also standing as a poor representation of the values of the Carioca School. Through the elimination of its masterplan, the value-engineering of its architectural details, and the subsequent invasion by the highway, Gávea is clearly a non-exemplar standard of the purest sense of the modernist vision dreamed by Europe.

Is it possible that the shifts in Gávea may be part of another legacy that subverts the modernist genealogy? Instead of being judged against a set doctrine, Gávea exists as a testament for an architecture that gains merit from its very ability to survive and negotiate the forces transforming it from the original model. Gávea offers glimpses into a process of urbanism and inhabitation that may be more representative of the forces of the city, and thus it may prove to be a more useful and appropriate lesson than its deficiencies imply.

Contesting the narrative

While architectural history books continue to use Pedregulho as an example of the optimistic accomplishments of Brazilian modernism, the complex itself fell into decades of disrepair and degradation. Soon after completion, the social functions of the complex would no longer be used or maintained, and the units themselves began to resemble the squatter settlements that they replaced. As early as 1966, Block A was being reported to be in a dilapidated state due to seepage caused by the malfunctioning of equipment. Because of its fame, architects and residents alike recently rallied and achieved landmark status for the work, thus gaining access to even more state-provided funds and resources for its renovation and maintenance.

Meanwhile, though Gávea also experienced natural wear and tear from decades of use, the block itself maintained a vibrant community and continues to operate efficiently today without major renovation or further government support. Regardless of failing to implement its planned social complexes, the surrounding neighborhood has filled in and become a vibrant and popular university area with facilities that include a planetarium, classrooms, theaters, and artist galleries.

Without attempting to declare subjective preference of one project over the other, the nature of their sibling rivalry instead draws a critical awareness to the faults in the homogeneous retelling of Brazilian modernism in relation to the assumed worth of the original European model. Alternatively, comparisons of value within the Brazilian-born minhocāo typology may speak more specifically to the ambitions of a regional architecture in service of the people. In framing the history of Brazilian modernism in this way, Gávea instead becomes a versatile manifestation of Rio’s shifting socioeconomic conditions that contests the pathological supposition that it is deficient.

Because of its symbolism as the DHP’s first social housing project, Pedregulho’s site planning and orientation was decided primarily based on visibility throughout the city. Stubbornly, the orientation of the project contradicted the basic principles of solar orientation and chose to face directly into the harsh northwestern sun. Residents of the elevated and exposed block became subject to unfavorable insulation throughout the day—a troubling baseline condition not particularly well suited to ever be a model for efficient housing. Out of necessity to mitigate the heat gain, and as another homage to Le Corbusier, Reidy would incorporate a series of brise soileil along the intermediate floor, and also include custom venetian blinds for every apartment. On the opposite eastern facade, protection and ventilation of the corridors was accomplished through screens made of traditional cobogó porcelain tiles. Though these architectural details greatly assisted in highlighting the regional adaptations of modernism, their very existence was caused by poor and costly site planning at the expense of the residents. In comparison, Gávea is nestled into the base of its forested hillside, providing cool and protected circulatory spaces to the south, and its less-harsh northern sun could be more easily mitigated by off-the-shelf internal blinds. As a baseline site planning decision, Gávea’s orientation naturally cut developmental costs while simultaneously creating a more comfortable and regionally aware housing environment.

While it’s not possible to pinpoint an exact cause for the failure of the social facilities at Pedregulho, one might look to the case of the laundromat as a situation indicative of a general disconnect between the imposition of a habit versus the cultural emergence of one. Although the shared laundry facility was declared an innovation due to its importation of modern equipment from Germany and its elimination of the “cluttered” aesthetic of drying clothing from windows, the mechanization and consolidation of the laundry process greatly disrupted a vital social habit that the residents came to appreciate in their day-to-day lives. An important culture of neighborly gossiping and entertainment was linked with pre-existing communal laundry habits; soon after occupying the neighborhood, residents began to appropriate the communal pool for washing laundry, as it provided a more desirable space to achieve the socializing they missed.

This oversight was corrected and incorporated at Gávea by adding an open-air rooftop level that provided every resident with her or his own dedicated wash basin and space for drying while preserving the social importance of the daily activity. Though Gávea would not be supported by other planned facilities for social interaction, over time it would accidentally learn to accommodate an open-air theater, games on the intermediary floor, and user-created home businesses that would transform the building into its own vibrant concept of community.

Already saving significant costs by reducing the masterplan to only Block A, Gávea would still face additional pressure to innovate with an ever-tighter budget. As a way to cut nearly a quarter of its built area, Gávea would thin its section from a depth of nearly twelve meters to around nine meters. Without adding any extra residential floors, the units on the upper floors would be redesigned to accommodate three units in the space previously occupied by two units, while the lower apartments would be redesigned to cope with the narrower bar width. Overall, these changes would result in a 17% increase in units when comparing the two minhocāo blocks—up to 328 units from Pedregulho’s 272 units. Outside of volumetric shifts, custom architectural details present in Pedregulho, such as custom-painted pool tiles, floor tiles, brise soleil, cobogó screens, and railings were cut and replaced with more cost-aware solutions. Though these efforts tend to privilege economy over beauty, they are all responses to the numerous controversies and criticisms born out of Pedregulho’s expensive, time-consuming, difficult, and overtly singular response to a very real housing crisis. Gávea would try to reconcile the prototype as a real possibility for providing mass social housing infrastructure, but in the process it would be perceived as flawed via these same shifts.

Gávea. Left to right: Circulation corridor, landscape interface, intermediary floor, laundry floor. Credit: Bryan Maddock

Re-evaluating the pair

As put forward through the analysis of Gávea, once Brazilian modernism is not considered in the context of European ideals, these once-incomplete works may actually prove critical to providing insights into alternative readings of the efforts of modernization. Between the global retreat of the state’s creation of social housing and the subsequent replacement of developmentalism by the global free market, the potential for experimental typologies of urbanism have become extremely limited. Works that have often been overlooked or disregarded as defective in the past may now serve as more complete genealogies of specific architectures in response to the socioeconomic conditions of their times.

The new knowledge gained through the comparison of these two projects is crucial at a time when architecture’s preoccupation is increasingly less engaged with social concerns. Behind the longstanding narratives praising Pedregulho and condemning Gávea is a larger professional struggle in defining what determines the value of architecture. While Pedregulho is representative of architecture as the physical embodiment of ideals, Gávea depicts an architecture that is valuable as a responsive tool for addressing urban challenges. As we continue to face many of the same urban questions confronted by Reidy in the 1950s, how we utilize and react to these comparative findings may largely define architecture’s role in dealing with the scarcity of housing and infrastructure still pervasive in the 21st century.

Let us put to rest the once-prevailing consensus that variations of modernism in South America were simply exotic regional tweaks of an imported model, and instead understand that the evolution of Latin American modernism reveals to us a laboratory that continues to generate new lines of inquiry. Latin America pursued modernity with a sense of willful failure—an intrinsic optimism in the process of discovery. What was seen internationally as the logical and conclusive death to modernist social housing should instead be seen as the foundation for the continued creation of proactive and self-sufficient exploratory architectures. It seems almost unreal in the context of today’s market economy to even imagine a world where architects led the conversation about improved social conditions, but if we look to the alternate histories of modernization we may be provided with evidence of how to re-engage with architecture as a socially equitable science of the city.

Acknowledgements

“A Serpentine Science: Affonso Eduardo Reidy’s Housing Pair” was made possible through the Architectural League of New York’s Deborah J. Norden Fund in support of travel research. Thank you first to the League and to everyone who helped me navigate Brazil during the documentation of these works—Letícia Mattos, Júlio Magro, and Nathalia Watanabe for being gracious hosts; Lee Ann Custer for assistance in visiting Pedregulho; Hamilton Marinho and Jorge Fafians for their generous access to the works and for their efforts in managing and maintaining these buildings; and especially Marcella Mattar for translating and supporting the entirety of these research travels. Thank you also to Yale School of Architecture and the Department of Architecture of Cambridge University, whose Edward P. Bass Fellowship program provided additional feedback and resources to accomplish this study. Special thanks to Elia Zenghelis for first introducing me to the work of Affonso Eduardo Reidy and for being a constant champion and mentor throughout these efforts.

Biographies

is an architect, Director of Fantastic Offense, and an Instructor of Architecture at The Design School at Arizona State University. Maddock’s ongoing research and design work emphasizes utopia as a strategic tool for proactive rebellion and a call for renewed professional agency. Prior to Fantastic Offense, Maddock was a project designer at Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) in New York and a designer at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) in Hong Kong.

Explore

Lina Bo Bardi’s return to Salvador

Angela Starita discusses the architect's (mostly unrealized) plan to restore the historic city center of Salvador, Brazil.

Potable water and local power struggles in Honduras

Timothy Kohut reflects on alternative visions for community development in Tegucigalpa.

The architecture of the Cuban revolution

Josef Asteinza considers the architecture of the Cuban Revolution and its impact on the city of Havana.