To combat climate change, focus on existing buildings

Architects are uniquely positioned to reduce global warming, argues the CEO of Urban Green Council—but first they need to rethink their role.

Within the past year, a number of architecture firms and allied organizations have formally declared a climate emergency and pledged to take action. But what should this action involve, and how likely is it to happen at the scale and speed required to prevent the worst outcomes of global warming? In this interview series, the League presents different perspectives on where architecture currently stands with regard to climate action, where it needs to go, and how it might get there.

Urban Green Council, a New York City-based nonprofit, seeks to make cities more sustainable by improving their building stock. Since it was founded in 2002, the organization has played an important part in the development of ambitious government policies in its hometown. One of these, Local Law 97, broke new ground in climate legislation earlier this year by setting carbon emissions caps for buildings over 25,000 square feet.

Urban Green Council CEO John Mandyck has an extensive background in business and environmental issues, having spent 25 years at Fortune 500 manufacturer United Technologies Corporation, where he served as Chief Sustainability Officer. He is the co-author of a book about food waste and climate change, and has served as a visiting scientist at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The League’s Sarah Wesseler spoke with Mandyck about the importance of existing buildings in the climate crisis.

*

This interview series focuses on architecture’s response to climate change, but you’ve also done a lot of work outside the field. Compared to other sectors you’ve observed, how well do you think architects are responding to climate change?

I think architects are the tip of the solution when it comes to buildings that will put us on the path to mitigate the worst impacts of climate change. I say that for a couple of reasons. One, the green building movement, going back to 30 years ago, was really propagated by architects, because architects see the challenges holistically, and therefore see the solutions holistically. The practice in general has been very, very instrumental in lifting the green building movement not only in the United States, but around the world. So I’m very grateful to my architect friends for that leadership.

Fast forward to today. I think architects are still the tip of the solution, because they can convince clients to think about how buildings can operate in a different way to address climate change.

But I do think there has to be a fundamental recasting of the role of architecture. A lot of architects love to work on that brand-new shiny building, and that’s awesome—but that’s not our issue. In New York City, 90% of the buildings we’ll have in 2050 are here today. When it comes to the built environment, the solution for climate change is literally in front of us; it’s not some new project down the road. Increasingly, we’re going to have to view architects as the people who provide solutions for existing buildings.

What do you see as the opportunities and barriers for architects wanting to take effective action on existing buildings?

In its broadest sense, the opportunity is through awareness. Architects often speak more directly to building owners than people on other parts of the value chain do. They command owners’ respect and attention. So they have a unique opportunity to help raise awareness and provide education on why a green solution is important.

That comment applies globally, but in the context of New York City, I think architects can play a huge role helping building owners understand the enormous disruption that’s at their doorstep given the new buildings emissions law and Local Law 97. We need people to act soon if we’re going to make that law successful—architects can play a really important role in providing the awareness that can help make that happen.

What do you see as some of the main barriers to that happening?

Well, one is that architects may not view their role as being educators, and in helping building owners understand how structures can operate differently for a low-carbon future. But they may need to start helping shape decisions in a different way.

A big part of this is defining the value proposition. A lot of decisions about buildings are made on a dollars-and-cents basis, which I get. But because architects can command the attention of the decision makers, they ought to provide awareness of the financial implications of their actions. If an architect is advocating for an environmental design option and it gets left on the wayside because of cost, I want to make sure that they’re really communicating the true value proposition. In the case of Local Law 97, what are the fines associated with the building? What are the risks when it comes to resiliency?

I think the market completely overlooks the fact that New York has $3 trillion of insured coastal properties. That’s twice the GDP of Canada. From a value preservation standpoint, we have a lot at stake in the existing built environment that is completely at risk to climate change. Architects can help building owners understand the economic benefits of a low-carbon building in a way that others may not be able to do.

What’s left out of discussions today is risk. What is the long-term viability of this building? If you’re designing a new building, it’s going to be here well beyond 2050. There is a real question of whether global coastal cities are going to function properly in that time horizon because of climate change. So taking the longer-term view and pricing in the features that would actually cut costs down the road would be would be really, really helpful. Because in my view, we’re going to pay for this—it’s just a matter of when. If we’re not going to pay to lower carbon emissions today to help the world mitigate the impacts of climate change, we’re just going to pay for it later in stranded assets, in storm events, in cities that don’t function the way they should because we never built in the correct pricing mechanism upfront. Architects can help provide that education and awareness when those decisions are being made.

I get the sense that architects themselves sometimes feel powerless, though—they can try to influence their clients, but at some point they can’t push any further. But you think they have owners’ ears more than other people do—more than, say, engineers or building operators. Is that just because there’s a kind of glamor factor that comes with the aesthetic dimensions of architecture? Or is there some other reason?

One primary reason is that discussions for any project, whether it’s a renovation or new construction, often start with the architect. The architect is brought in earlier than others in the process, so they have the opportunity to set the tone, set the goals, and provide that education and awareness that the decision maker needs early in the process.

The timing is very important. Once the plan’s done, the building’s designed, and you get to construction drawings, it’s almost too late.

A lot of Urban Green’s activity focuses on building retrofits. Can you give me an overview of this work?

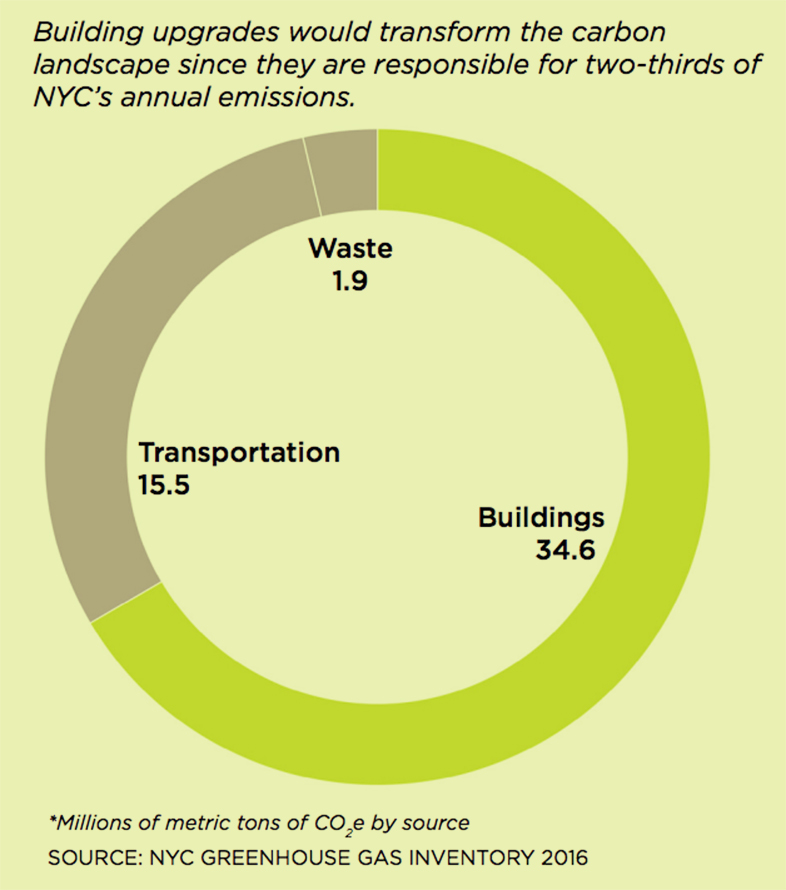

To start with the big-picture perspective, New York City has a law to reduce climate emissions 80% by 2050. Two-thirds of those emissions come from buildings, and 90% of the buildings that we’re going to have in 2050 are already here today.

Urban Green Council graphic showing New York City's carbon emissions sources. Credit: Urban Green Council

So when you follow that math, it tells you that we need to tackle retrofits of existing buildings. Almost all our work is dedicated to that space: trying to find ways that we can retrofit our buildings to achieve the carbon emission reductions we need.

When you look inside buildings to see what’s going on in terms of emissions, you realize that many different retrofitting strategies are needed. The number one source of emissions in New York buildings comes from burning fossil fuels at the building. It’s not from the plug load, it’s not from the lights—it’s natural gas that’s burning inside steam boilers for space heat or hot water, primarily in multifamily buildings. But the kinds of retrofitting strategies you need to deal with this issue may be completely different than what’s needed for a commercial building, for instance.

So there’s not a one-size-fits-all solution. Within each building type, there is a long, long runway for how we can achieve the energy efficiency and the carbon reduction we need.

Can you tell me more about Urban Green’s work on legislation around these issues?

Almost three years ago, we convened the city’s experts to come up with consensus recommendations for putting buildings on a path to meet the 80 by 50 reduction goals. That produced the Blueprint for Efficiency report, which really became the architecture for Local Law 97.

Now, the law ended up in a different place than we were recommending. The Blueprint for Efficiency recommended an energy efficiency law, whereas the law ended up being a carbon reduction law. Both get you to the same place, but in somewhat different manners.

When we saw it was going to be a carbon law, we jumped in and worked hard to make sure that it would actually work. One of the issues with a carbon law versus an energy efficiency law is that it penalizes density. The law works through a carbon-emission-per-square-foot cap for 10 different building types. The problem is that you could have super energy-efficient buildings that just use a lot of energy. We have a number of LEED Gold and Platinum buildings in New York City that don’t comply with this law. That doesn’t mean they’re not green buildings, or that they’re not designed and operating efficiently. They just use a lot of energy.

I’ll give an example—if you have a building with 8,000 people in it, it could be the most efficient skyscraper out there, but you’re not going to get around the fact that it has 8,000 people. Now, if the building also has two data centers and three trading floors and it operates 24/7, it’s just going to use a lot of energy. A carbon law is just blind to all that.

There will be an opportunity to address this density challenge with the advisory board that will guide the implementation of the law. In addition, we’re examining the role building carbon trading can play in helping building owners meet the requirements in buildings where no matter what they do, they cannot meet the cap through energy efficiency alone. They might be able to meet it if they’re trading with another building that can go below the cap, though.

Based on your experience, do you think architects understand how to take action on these issues? Do they have the tools and information they need to have a real impact on the timeline that’s required to prevent the worst outcomes of climate change?

There’s a wide spectrum. You have many, many firms that specialize in sustainable design. You have others that are just starting their journey in recognizing that climate change is an issue but not understanding what they can do about it as architects.

For those that are starting the journey, there are many, many resources—including the resources at Urban Green—that can provide awareness of trends and policy directions, but also provide training and education. We deliver training for the state’s energy code, which becomes the basis for new building design. We provide green professional training. I was in one of our trainings this morning, and there was a wide range of designers, operators, building maintenance staff just trying to understand, what are the basics of climate change and what role can buildings play? This year, Urban Green will have done 53 programs. Literally every week you can go to an Urban Green event where you can learn more.

And earlier this year, Urban Green joined with AIA New York and the New York chapter of ASHRAE to launch something called the Cross-Learning Alliance, which is an educational partnership that brings cutting-edge programming to the building industry. So this initiative brings together the city’s leading organizations for architecture, engineering, and green building to develop educational priorities to bridge gaps and promote dialogue and information sharing.

So those resources are out there. They’re at AIA, they’re at ASHRAE, they’re at Urban Green. It’s just making a conscious decision that yes, I need to broaden my own vocabulary on the subject.

Explore

New York, climate change, and sea level rise

A prescient 2008 lecture by climate scientist Klaus Jacob.

James Wescoat: Climate, energy, and water-conserving design

Landscape architect James Wescoat discusses water supply and other hydroclimatological conditions in major American cities.

Climate change in the American mind

Anthony Leiserowitz is joined in conversation by Kate Orff, Paul Lewis, and Dale Jamieson to discuss underlying values that are reflected in our various views of climate change, and the extent to which those views are based on cultural predispositions rather than scientific data.