Transversal modernity: Spatial discourse in architectural paper projects in Iran, 1960–1978

Shima Mohajeri examines a 1973 design proposal for a civic center in Tehran by Louis Kahn.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Shima Mohajeri received a 2010 award.

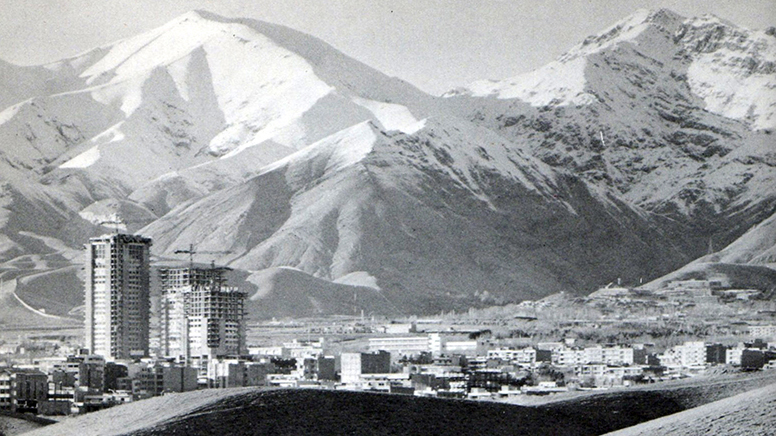

Toward the end of the 1970s, when Michel Foucault, following his short visits to Iran, called the shah’s pseudo-modernization agenda a “dead weight” or “archaic” form of modernity, he posed a critique of state power that had imposed a dialectical tension between modernity and traditional history in Iran. While the shah’s modernization plan was an attempt to fast forward a traditional culture into a Great Civilization parallel to that of the West, the shah’s alternative court, run by the queen, initiated a campaign to incorporate history and tradition into these recently fabricated modern landscapes. Under the patronage of the queen and her cultural protégé, the shah’s progressive and rapid modernism underwent criticism. The counter-rhetoric of nature and culture, decentralization strategies, and heritage preservation became key concepts that were negotiated during numerous symposiums and intellectual venues. This soft and almost reverted vision of modernity took place in the period following the 1963 White Revolution when a series of development plans were hastily introduced into Iran’s socioeconomic structures. These two renditions of modernization—arising from the two courts—developed a condition of crisis that created, on one side, various forms of cultural and ethical emptiness, and, on the other, totalization and the false return of past traditions that continually resisted all forms of undeveloped and displaced modernity.

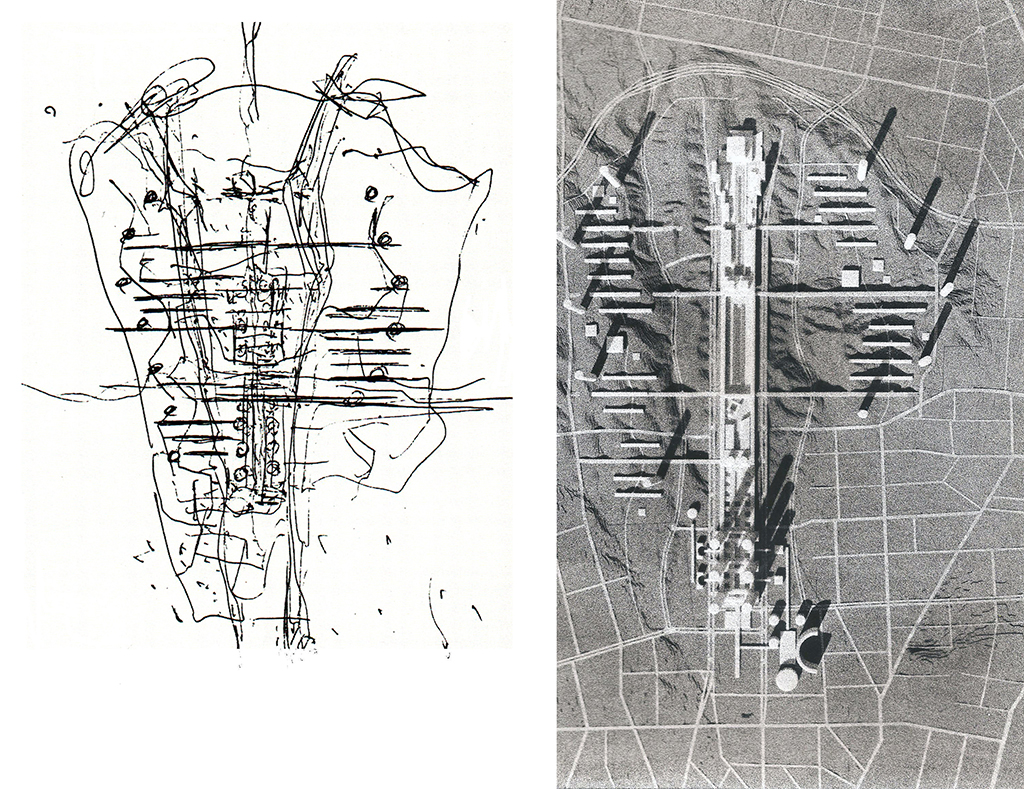

Kenzo Tange, Proposal for the Abbas Abad New City Center, 1974. Credit: Kenzo Tange, “Abbasabad New City Center.”

It was amid this dichotomous space of power and cultural place that Louis Kahn visited Iran to participate in the first International Congress of Architects in Isfahan in 1970. Three years later, with the advent of the oil boom, Kahn and Kenzo Tange were commissioned by the two courts to collaborate on a design proposal for a New Civic Center in Abbas Abad district that was supposed to house the growing population of Tehran within the focal point of modern social and economic institutions. Kahn’s and Tange’s individual layouts show the struggle between the shah and the queen and thus become sites of reflection of the tensions in the Iranian society and the unfinished resolution between the polarities of power and culture.

My trip to the Louis I. Kahn Collection was therefore intended to provide me with a range of archival materials in order to reconstruct Kahn’s proposal for possible changes to Iran’s dual failures and its divided strategies of modernization. Through reading multiple drawings, sketches, photographs of models, and correspondences, I learned that Kahn’s short venture into the Iranian culture does not result in a universalizing account of modernism by translating or imitating the Islamic Orient and its material culture, nor is it a search for archetypal forms and transcendental structures that extend across the globe. For Kahn, the encounter is governed neither by formal and visual analogies and resemblances, nor by casual relations and cultural hierarchies in order to trace the genealogy of ideas. Rather, Kahn’s unrealized democratic layout for a modern public space in the heart of the Iranian metropolis suggests his indirect resistance to authority in its manifest dichotomy between a politicized and institutionalized culture and identity. Kahn’s design approach in the Abbas Abad master plan poses a decisive challenge to the shah’s progressive modernity, while transforming the modern traditionalist’s regressive outlook.

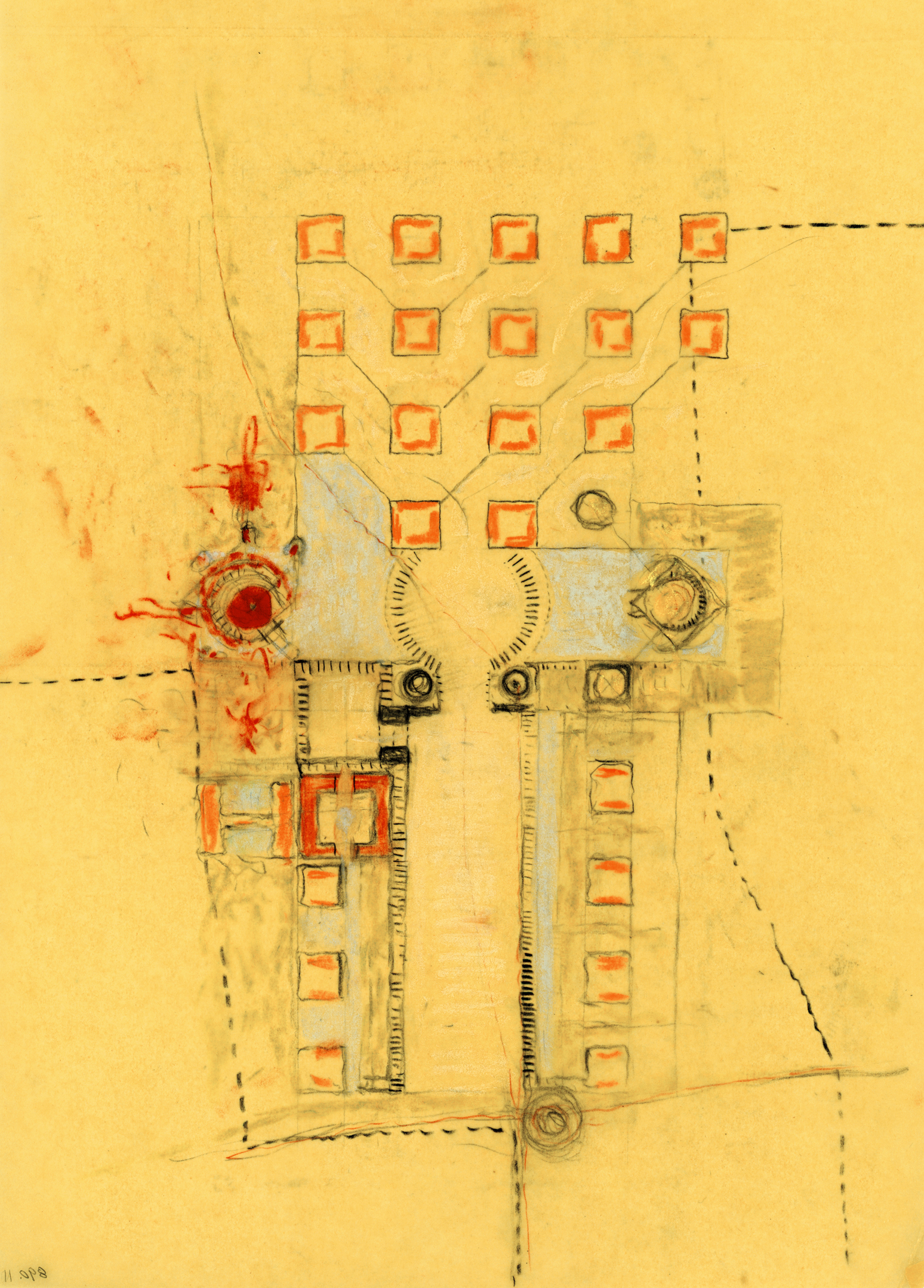

Louis Kahn, Clay Model of the Abbas Abad Project, 1974. Credit: the Louis I. Kahn Collection, The University of Pennsylvania.

The study of Kahn’s master plan in the context of a simultaneous critique of power/culture within the complexities of a developing metropolitan site reveals a new schema of public space for Tehran. This democratic model of publicness is differentiated, in Kahn’s design, from a totalitarian approach that constructs, displays, and petrifies power and cultural history into a mute background space. It also challenges a strictly functional notion of space for civic assembly that excludes the traditional and cultural heritage. The site of public life in Kahn’s outline permanently constructs and deconstructs the binaries of power and culture and their forms of domination and resistance in order to open up an overlapping space of critique, exchange, and action. Kahn’s blueprint carries the polarity between a politically engaged culture and the culturalization of politics over into the public sphere without dissolving the two theses. Yet Kahn’s characterization of democratic space, more akin to Hannah Arendt’s idea of “active citizenship,” is informed by an indirect resistance to the two opposing views, which in turn allows architecture and public space to survive as a practical site of critique of society and its cultural and political positions.

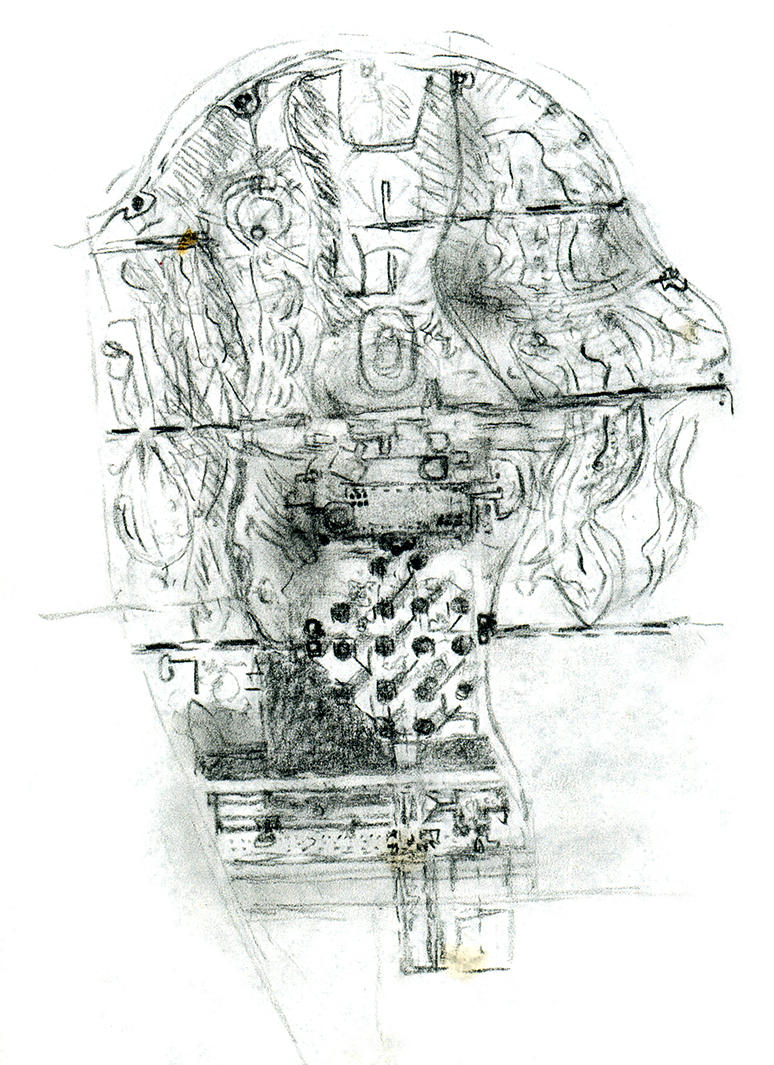

Louis Kahn, Early Sketch of the Public Space, 1974. Credit: the Louis I. Kahn Collection, The University of Pennsylvania.

Finally, this analysis reveals the work of Kahn as a silent, invisible practice that is later excluded and erased in favor of a conservative plan. As I suggest, this tragic encounter of modernity with cultural place is not a sign of failure, but rather can be understood as a transversal practice that remains invisible and disguised as a political manner of resisting the traditional, representational, and hierarchical structures of space. It is precisely this absent and unfinished account of transversality that I wish to render positive in Kahn’s work that promise a new reality, a new ethos as the intensive globalism yet to come.

I am currently developing ideas from my dissertation into a book-length manuscript. It further studies the paper architecture and master plans developed by other canonical figures of modernity such as James Stirling, Alison and Peter Smithson, Alvar Aalto, and Kenzo Tange, who practiced on the historical fringes of postmodernism during the 1970s in Iran. In parallel to my book project, I plan to curate an architectural exhibition on the theme of Unbuilt Tehran that will address the relationship of these unrealized blueprints designed by modern architects and the sociocultural, political, and urban conditions in Iran. This exhibition brings to life the cartographic and urban imaginary of the architects under study and explores new ways of historicizing, documenting, and re-animating unfinished works.

Louis Kahn, Final Sketch of the Abbas Abad Master Plan, 1974. Credit: the Louis I. Kahn Collection, The University of Pennsylvania.

Biographies

is a trained architect with a PhD in the history and theory of architecture from Texas A&M University. She is currently working on the manuscript of her first book, which connects the cultural theory of space with specific aesthetic and architectural practices in the history of modernism that are entangled with the past and present of Iran, its artifacts, and its politics. She taught design studios in the College of Architecture at Texas A&M University and Azad University in Tehran.

Explore

Re-reading ornament: Textures in Islamic Spain

Fiyel Levent describes an art and architecture of tolerance from medieval Andalusia.

Connective spaces and social capital in Medellín

Jeff Geisinger investigates the built environment's impact on social capital in Colombia's second-largest city.

Glenn Murcutt lecture

The architect discusses his design process for the Australian Islamic Centre in Melbourne.