Re-reading ornament: Textures in Islamic Spain

Fiyel Levent describes an art and architecture of tolerance from medieval Andalusia.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Fiyel Levent received a 1995 award.

The original intention of my project was to explore the concept of tolerance as it was represented through ornament and ornamentation in Andalusia, a region of Spain that was once under Islamic rule. After visiting and delving deeper into the area’s rich history, the role of toleration took on more complex flavors. I became interested in how this concept of toleration could be read into the variety of built forms and histories of the Andalusian Islamic empires.

The story of Andalusia reads very differently from an Eastern perspective than it does from a Western one. To the latter, Andalusia’s Islamic rule was the result of an Eastern invasion of a land belonging to the West. From this perspective, the long period during which Islamic power flourished in the Iberian Peninsula is usually regarded in terms of the “Reconquista,” the 800 years during the Middle Ages when Spanish monarchs were committed to retaking the lands that they had claimed to be their own. This was a conquest that would not end until the last Muslim power was cast off of the European continent, a goal roughly accomplished by 1492, at the dawning of the Modern Era.

When viewed through another lens, however, the period of Islamic presence in Andalusia, which began in 710, brought with it a multitude of advances to many sectors of society. Especially during the first 300 years, it was notable for its degree of cultural integration. It produced intellectual centers that were incubators of thought and art, generating work that was significant to the development of the European Renaissance to come; it was a period that could realistically be considered in terms of a modernizing society. One of the key reasons for the successes of this society was the peaceable coexistence of a large variety of ethnic groups. Tolerance for cultural and racial intermixing was a major component of certain governments, even moving towards a secular understanding of Islam as a religion that welcomed a dialogue with others. This tolerance led to a few centuries of prosperity, manifested through an explosion of artistic production.

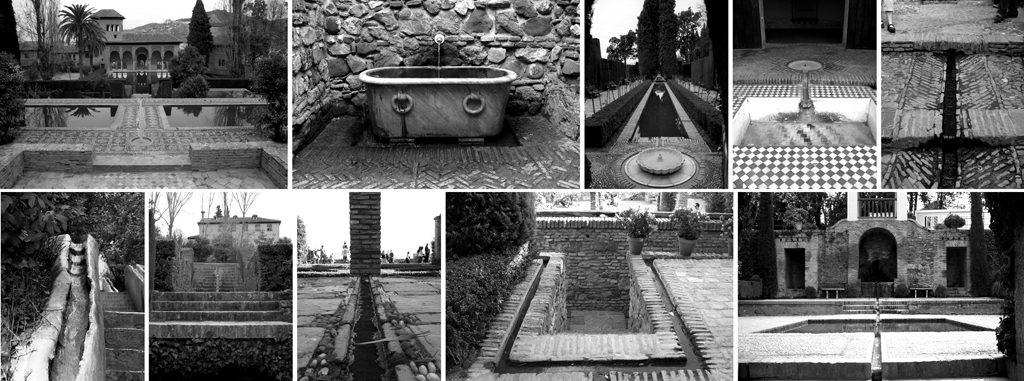

On water

One of the main technological advancements brought from the East to the ravaged Visigothic lands was in the agricultural industry. The existing populations had very inefficient farming practices that produced low yields and often overworked the land. The introduction of advanced irrigation and fertilization techniques, among other improvements, developed within the population a more productive and respectful relationship with the landscape. There were five great rivers through which they drew their energy: in the north, the Ebro and Douro Rivers, the Tajus River, the Guadiana River and the Guadalquivir River, with it’s tributary the Genil River. The eastern invaders knew how to make healthy use of these resources, and because the leaders enjoyed generally long reigns, they were able to conceive of long-term infrastructural projects.

The Andalusian people developed a great tradition of collecting and experimenting with exotic plants. The abundance of traveling and exchanging that was done between the Middle East and southern Spain afforded the culture a vital exchange of seeds and a colorful palate of flora. A great many chronicles and manuals were written concerning botany and agriculture, and it is through these texts that we are able to deduce the extent of their indebtedness to agricultural cultivation and its pervasiveness in day-to-day life.

This spiritual relationship with the landscape was reified in the architecture of the garden and by the water features that permeated urban and private spaces. The garden was always considered an art form in Islamic societies, revered for its religious symbolism. But in Andalusia, because of the great prosperity to be derived from the landscape, the garden was cultivated as a lifestyle ornament. Some patios had sunken gardens with pathways, from which one could easily pluck the oranges from the trees. Eventually, the garden was developed into a sophisticated microcosm of this landscape, an architectural space that honored the landscape and agriculture. The garden was developed into a jewel, a luxury that stood framed against the cultivated, pragmatic landscapes of food production.

Water played a significant role in gardens, as well as in other architectural spaces. Water features could be viewed as part of the spiritual conception of landscape when considering the confluence of rivers that were so important for irrigation and energy. Water was also used architecturally to serve many functions beyond the symbolic: as a cooling mechanism, a divider of spaces, and as a source of visual and audible sensations. Water could be moving in channels, creating soothing sounds in some spaces, while in other spaces the absolute stillness of a large pool would create almost perfect reflections of the surrounding architecture.

Cordoba, the template

The height of the Muslim empire in Andalusia occurred between the years 750 and 1031AD, with the city of Cordoba as its political and intellectual center. The exiled heir of the caliphate in Damascus, Abd al-Rahman, a half-Arab prince born of a Berber mother, whose family was murdered while he himself barely escaped, established his capital here by uniting the various feuding Islamic tribes that had arrived a few decades earlier. Cordoba was thriving, and the welcoming of foreigners and funding of places of culture allowed the arts to flourish. Architecture was abundant in the form of gardens, universities, public baths, massive libraries and mosques. The mosque typology in Muslim culture is immensely important, and central to its architecture was the presence of ornament.

The mosque of Cordoba is one of the most important remnants of this period. Built upon Roman and Visigothic ruins, the mosque has continued to add more layers, receiving additions and amendments from subsequent owners. The mosque was built with a non-hierarchical plan, as a civic institution for the people of Cordoba. It is a hypostyle structure; a flat ceiling supported by columns — in this case, a vast grid of columns, creating the impression of an endless space. The public portion of the mosque is left unadorned and here there is no privileged portion, no “center” to the building. The space is not processional, as one is not meant to follow a certain prescribed path or narrative, but rather to wander. As stated in the philosophy of Islam, wherever the worshipper is standing, that, for him, is the center of the mosque, of the structure, and of the world.

Elaborate ornament adorns the space above the area for public prayer. Stone horseshoe arches fly overhead, supporting the roof, arch on top of arch. They are alternating red brick and white stone, a kind of vaudeville act for the senses occurring above you. The Roman aqueducts of Mérida provide some precedent for these structures. The horseshoe arch is an element of indigenous church building tradition both before and after Muslim rule in Spain. Some of the columns are recycled from ruined churches and Roman civic buildings. In a common practice of Andalusian architecture, these architectural remnants were assimilated into the structure, creating a dialogue between the revived indigenous cultures and the newly thriving one.

The importance of this mosque as a major public space is evident in a study of its many doors. Entrances on all four sides invite the population in, not giving preference to any one approach. Some enter into the gardens, others directly into the place of prayer. The centuries of transformations of this work, from church to mosque to church to cathedral as it changed hands numerous times can be read in the multitude of styles present in the architecture of its gates and portals.

Another unique characteristic of this mosque was its orientation in the city. The young emir was a romantic living in exile who yearned for a way of life that he could no longer have. During his reign, he was self conscious of being in this new frontier on the fringes of the known Arab world, bordering on the vast Christian lands of medieval Europe. As one historian, Menocal, has written: “The early Muslim settlers developed a cult around memories of the Umayyad Dynasty in Syria; they compared existence in Spain to a fantasy of what life had been in Syria, and they gave Syrian names to their creations in Spain.” And so, in a dramatic gesture, the emir decided to take back Damascus. He did not orient the Mosque towards Mecca, as is prescribed in Islam. He situated the mosque towards Mecca as though he were still in Syria, as though he were standing in Damascus and building it there. This was his response to exile. It was with this nostalgic orientation that the template for this society was laid out.

Ornament and framing

Ornamentation is a central feature in many Islamic architectural types, and Andalusia was no exception, developing its own unique characteristics. In his book, The Mediation of Ornament, Oleg Grabar discusses the nature of geometric arts, commenting: “The areas and times that most consistently exhibit geometric ornament are at the periphery of major cultural centers or at the edges of dominating social classes.” However, he goes on to say, “…quite the opposite occurred in the Muslim world.”

Framing was also an incredibly important element in the architecture, at both small and large scales. Both in terms of internal surfaces and spaces (how one views the architecture), as well as the external views afforded from the windows (how one views from the architecture). The architecture was designed so as to visually fuse the ruler with his landscape, considering where his throne was placed, and where he greeted his visitors with the backdrop of this kingdom behind him. The landscape and cities themselves could thus be considered as ornamental. Indeed, the term mirador — balcony, in Spanish — implies a space of viewing.

Granada, 1492

Towards the end of the 11th century, internal divisions led to a weakening of the state, and a fundamentalist turn began to pervade the society. Intellectuals and producers were made unwelcome, ethnic discriminations became more pronounced. The empire divided into separate factions, and gradually declined for the next 400 years. The last of the Muslim dynasties in Spain was the Nasrid, who ruled from the capital city in Granada. As each of the remaining factions fell to Christian hands, Granada remained a refuge for Muslim artists and intellectuals, many of whom were unwelcome under the Christian powers of the time. It was in Granada that the last architectural remnant was produced, the Alhambra.

The Alhambra was an old fortress on a hill that began its gradual transformation into a palatine city by the first Nasrid king. It was composed of numerous palaces, gardens, bathhouses, and fortifications that were built over a few centuries and then continued to transform under Christian control.

Due to the greatly diminished territory and loss of power of the Nasrid dynasty, there was a reduced capacity for lavish spending on architectural works. The palace of the Alhambra had to be built quickly from cheap and local materials, stucco and local stone. It is at this palace that the idea of the geometric ornament became associated with prefabrication and mass production. Because it was to be quickly made, having one repeatable module helped the craftsmen determine how to assemble the surfaces and textures of the spaces. Much like the Mosque of Cordoba, this palace was built on a strong sense of nostalgia, but this time, nostalgia for the old caliphate and empire of Cordoba, which at this point had already fallen into the hands of the Spanish monarchs.

Picture of the exteriors

Elements of a tolerant mentality under the Nasrids can be read in the varying treatments of the interiors and exteriors of the Alhambra. When viewed from the outside, there is a certain aversion to monumentality. Although the emirs held sovereign power, the exterior of the palace did not boast of their strength. The face of the fortress-palace was made of unadorned surfaces of local red clay. The insides are almost the complete opposite, detailed to an incredible, yet not oppressive, degree. The ornamentation is delicate, small, and incredibly intricate.

Naturally, there was a ceremonial aspect to the spaces of the original Alhambra; the more important the visitor was, the deeper he was allowed to go. The ceremonial spaces had no set program and in this way the spaces took on the role of a theater. The program was set by what the occupant was doing inside. The labyrinthine character of the spaces, the symmetry, the hypnotic nature of the surfaces and the ornament were also conducive to security; they confused the visitor, and controlled his perception of where he was.

In the Islamic empires of Andalusia, periods of prosperity were marked by a desire for cultural integration, social freedoms, and acceptance. The periods of decline were marked by exclusion and the restriction of freedoms for specific groups. They practiced an intolerance of diversity and preached a need for submission to an authority. The decline of a civilization means also a decline of its art and cultural production. Prosperity begets art and, for the ancient cities of Andalusia, that art is imbued with the tolerant ideology of its leaders and people. The geometric ornamentation, the gardens, the public spaces, the monuments, much of these are left as artifacts upon the urban landscape, many still being excavated, left to be comprehended by future peoples. These histories are difficult to erase, and as empires came and went some conquerors had the foresight to preserve these memorials of knowledge. In some cases, the artistic knowledge was assimilated and evolved, producing new hybrid art forms. In Andalusia, this tolerant mentality carried through to some of the Christian kings, who, upon conquering the Islamic cities, borrowed from the techniques that they found there, producing a style known as Mudejar, one of the best examples of which is the Alcazar of Seville.

Biographies

was born and grew up in New York City. She holds a Bachelor in Architecture from The Cooper Union, and a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Literature from The University of Edinburgh, Scotland. Upon returning to New York from Scotland, she began working at Anik Pearson Architect, and has since managed various architectural projects ranging from ground-up buildings to apartment renovations. In 2009, Levent launched her own studio, completing projects and ongoing experiments in architecture, art, product design and interior design. By using the simplest of materials such as paper and wood, to more complex materials such as Corian and recycled Polyethylene, many of her designs involve combining and reinterpreting traditional forms with contemporary fabrication techniques. She aims to design and build custom architectural installations that achieve something close to the sublime in their relationship to light.

Explore

Bernard Khoury: Where the hell are the Arabs?

Bernard Khoury presents several projects from his eponymous firm.

Constructed landscapes

Michael Sheridan looks at landmarks of 20th-century European architecture to explore the relationship between buildings and their environments.

Light and proportion in the Cistercian monasteries

Naoki Seshimo writes about his exploration through drawing of the Cistercian monasteries in southern France.