Tokyo’s pantry: Tsukiji and the commodification of market culture

Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean write about Tokyo’s Tsukiji fish market, which the city plans to relocate in time for the 2020 Olympic games.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean received a 2013 award.

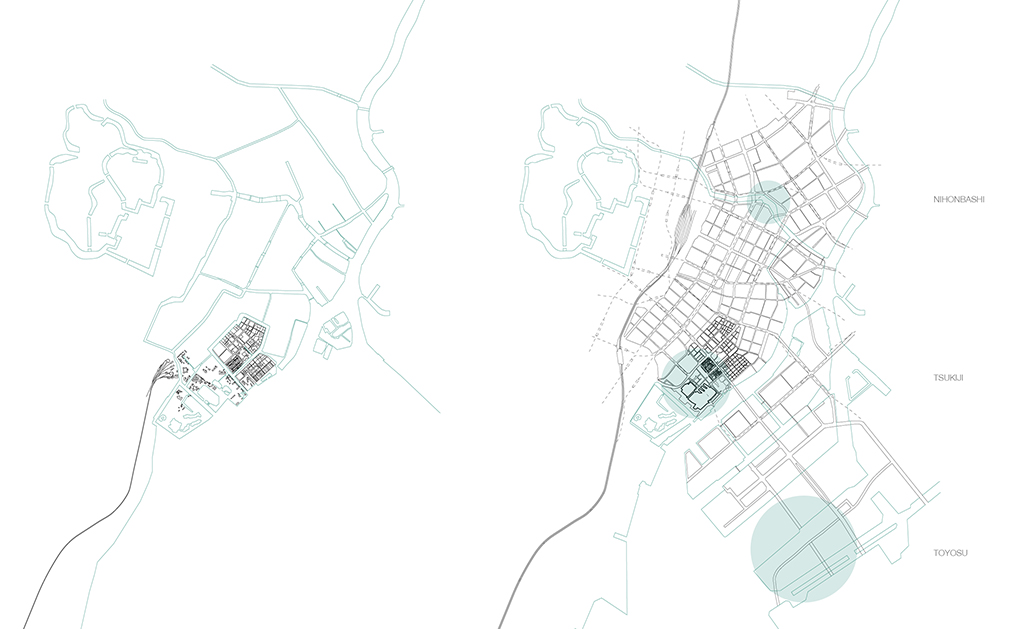

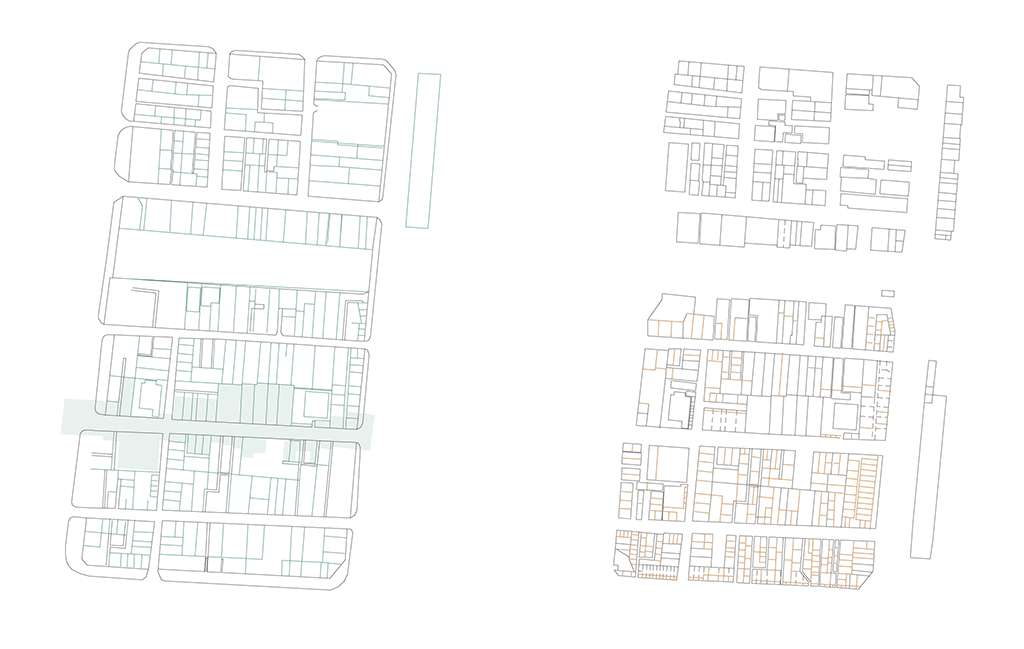

Area maps: Chuo-Ku (1880 / 2013), showing the Nihonbashi (-1923), Tsukiji (1935-2016) and Toyosu (2016-) market sites. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

Tokyo’s Tsukiji Central Wholesale Market is the largest fish market in the world. It defines a neighborhood that sits at the geographic heart of the city on prime waterside real estate, in the Chuo Ward (literally “central ward”), adjacent to the luxury shopping and entertainment district of Ginza. Chuo-Ku has long been associated with fishing industry and culture: it was where Tokyo’s original Nihonbashi fish market stood until the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

On March 29th, 2012, a plan to relocate the market to Toyosu, a parcel of reclaimed land in Tokyo Bay, was approved after a decade of controversy. The years of deliberation and political infighting preceding the decision and the still unceasing calls for a rethink attest to the great importance attached to Tsukiji by its local government, its merchants, and Tokyoites at large.

Site maps: Tsukijicho (1880 / 2013), showing the original Shimbashi station and the current railway line. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

Tsukiji, meaning “reclaimed land,” was rehabilitated and reclaimed after the Great Meireki fire in 1657 and was dotted with canals, whose path many roads follow today. The fish market was relocated to Tsukiji in 1935, in what was previously a quarter for the foreign merchants and missionaries of Tokyo. Whilst Edo (former Tokyo) had relied almost entirely on water-based transport, Tsukiji was built when the railways were in their prime and was directly connected to the station at Shimbashi.

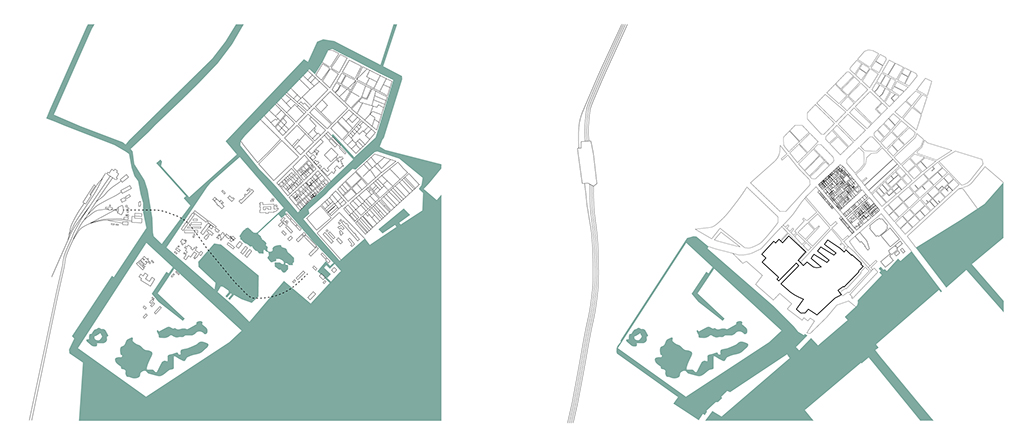

Tsukiji market plans (1935 / 2013). Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

The original building, said to be Bauhaus-inspired, was curved to incorporate a rail line and had multiple piers for unloading from the water. Since then many additional buildings have appeared to accommodate now dominant road-based modes of transport.

As the distributional center for the domestic and international fishing industries that feed Japan as an entire nation, the market provides an interface between multinational suppliers and producers, the small-scale shopkeepers that still hold a large stake in Tokyo’s food retail, and members of the public. For this reason Tsukiji as it is now appears doubly paradoxical in the context of contemporary urban economic logics: it is both distributional warehouse and farmer’s market exactly where we would not expect to find them: in the center of the city.

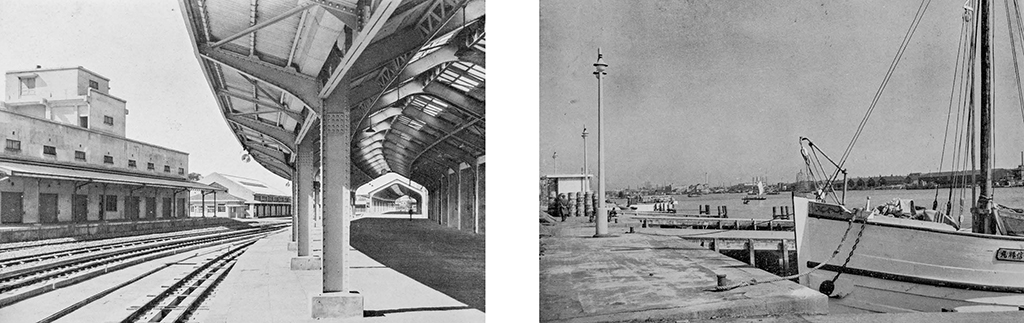

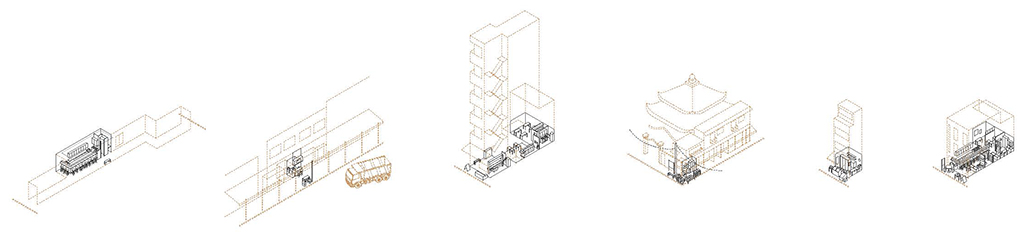

Archive photographs: train line and loading piers in the original buildings, 1935. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

Rail and boat were the primary modes of freight transport at the time the market was built, but due to the rapid improvements in delivery services everything now arrives by refrigerated truck. Tsukiji is increasingly congested with the volume of road vehicles. New highways and bridges are currently being built to service the new Toyosu site. Cart-based deliveries to the sushi restaurants of Ginza and Tsukiji will be a thing of the past.

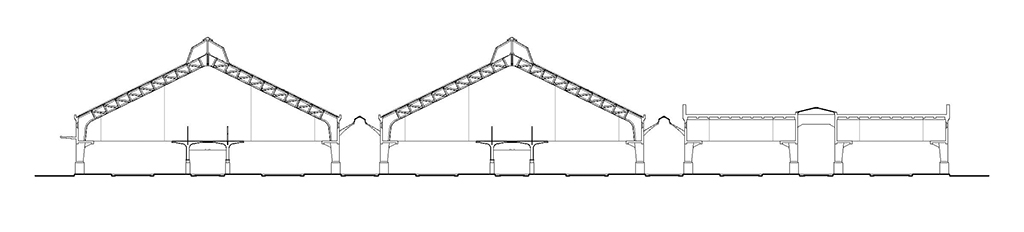

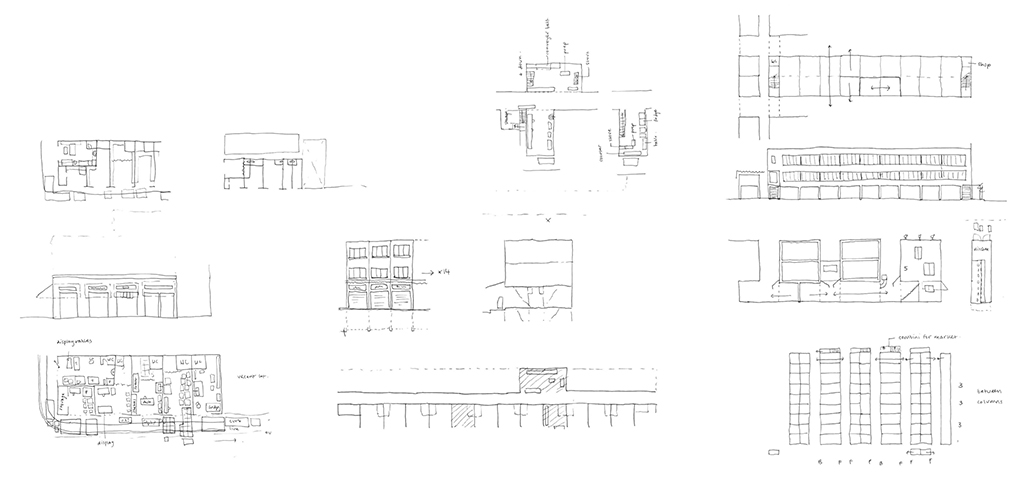

Inner market building section. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

Whereas elsewhere phases of the city’s food supply infrastructure are becoming more separate and decentralized, Tsukiji is still a place where various kinds of exchange are occurring simultaneously. Trade operates either within or without the regulation of Tokyo’s Metropolitan Government, under its Central Wholesale Market legislation. These are known figuratively as the “inner” and “outer” markets respectively. Inner and outer markets have architectural correlates, but the complexity of trading is such that regulated and unregulated trade may occur at any level.

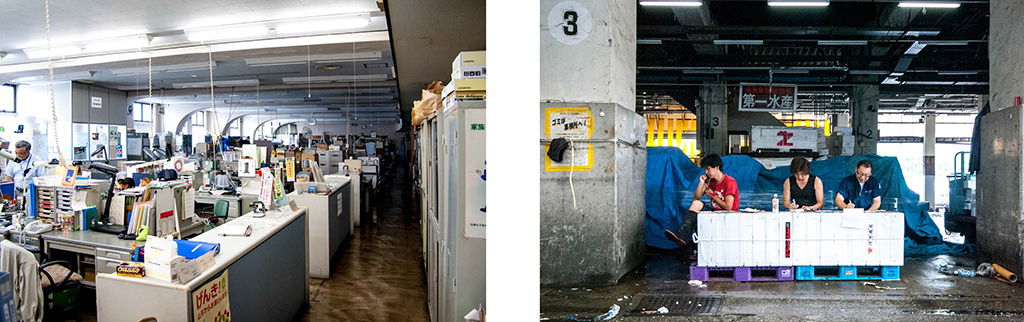

The inner market comprises auction houses, offices, loading bays, and, in giant sheds, all of the intermediate wholesalers. A permanent steel infrastructural frame carries water, morehart air conditioning and heating, electricity, and phone lines to each stall, the open sides and roof lights making for a light and well ventilated space. In a tradition of heavy tiled roofs, the glazed elements of these buildings were quite revolutionary at the time.

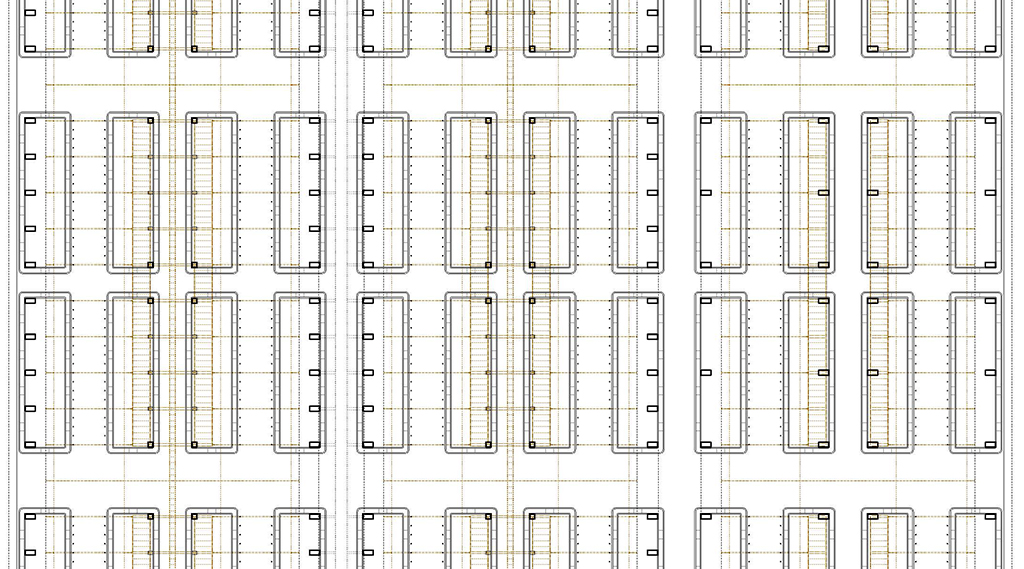

Inner market plan detail. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

A regular grid of columns and fixed infrastructure lies behind the controlled chaos of the inner market. Aisles alternate for front and back of house. Stallholders’ territory is marked by regularly placed steel caps in the floor, where some have only two, some up to twenty. Informal boundaries are studied and agreed upon between adjacent stallholders.

The fact that stall positions in the inner market are reassigned every four years in the name of fairness indicates that location matters at Tsukiji. Wholesalers will join forces to enter the stall lottery to secure a better location and to forge alliances, bringing in new customers. Adjacency to a particular auction house or a more generous corner lot can be an essential spatial advantage. The lottery has not taken place for the last eight years because of the imminent move.

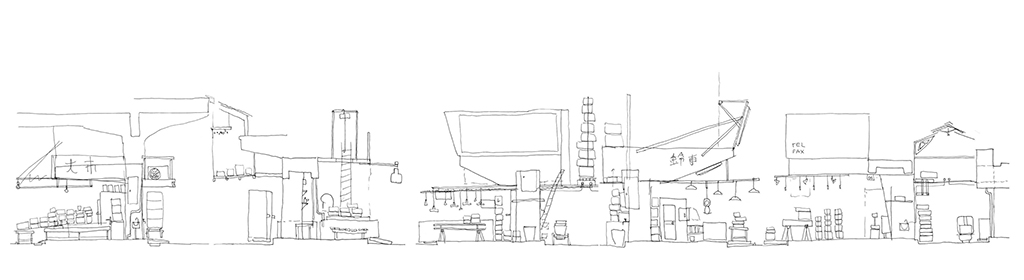

Inner market: sketch stall elevations. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

Merchants construct their own storage or office spaces above their stalls, each appropriating the given infrastructural frame in a different way. When the stalls are reassigned, all of this is demolished and rebuilt in a new location.

Outer market: land ownership patterns and stalls within buildings. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

The outer market, stuffed with retail fish stalls, knife specialists, sushi restaurants, and freezer stores, is a typical traditional Japanese urban pattern of small, narrow lots and narrow streets barely wide enough for cars. Land ownership can have up to three layers, and navigating the relationship between landowner, building owner, and strong rights for tenants and subtenants means that development can be slow.

There is still a major temple in the area and many of the shrines that once formed the approach still remain, now rented out to merchants as stalls. The outer market is closed by 2pm, and all of the temporary elements are put away. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

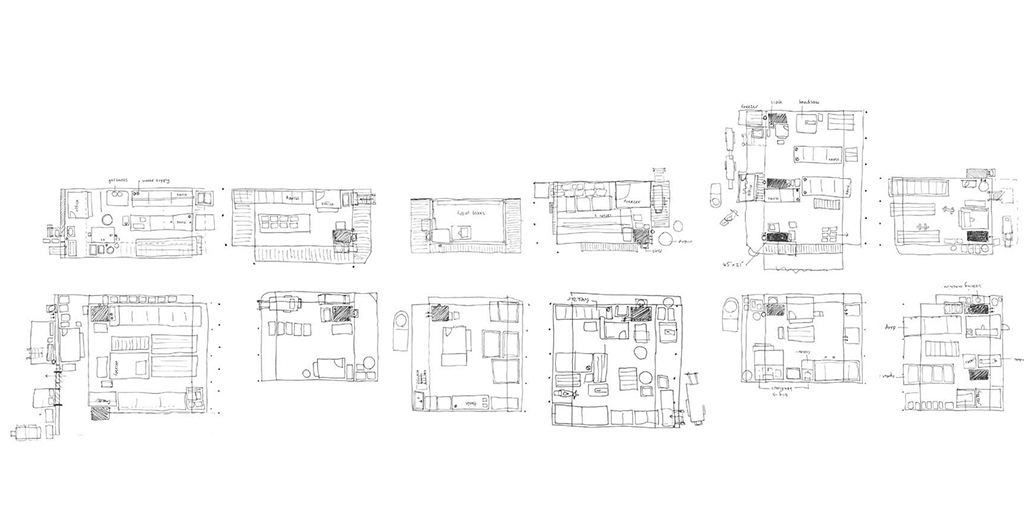

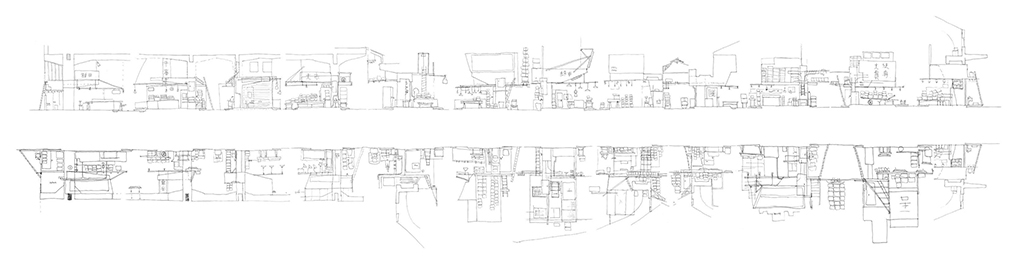

Outer market: sketch plans and elevations. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

Markets connect us to an ancient form of public life where goods were traded for both politics and pleasure and where the market existed simultaneously as both workplace and residential community. The tradition of the machiya (the Japanese merchant-house typology) lives on to some extent in the outer market, with the extended roof canopies and an entirely openable ground floor for retail with residential quarters above. Shopkeepers’ associations are strong in Japan and work to promote social ties and the continuity of community along each street in the outer market.

Tsukiji plays host to a spatial consolidation of the multiple stages of exchange in urban food supply: stages that are elsewhere growing increasingly separate, disparate, and invisible. Tsukiji’s connection to trade at all levels and its openness to the public still play a crucial role in its urban identity as both guardian and heir to a conception of preindustrial mercantile Tokyo.

Licensed retailers buy tuna at auction in the inner market and cart it around the corner to sell on the street (or in a coffee shop). Tuna, along with sea urchin roe, is one of the few fish still sold by auction as local government loosens its control over market trading to favor larger supermarkets. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

Outer market: case studies. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

Every inch of space is maximized in the outer market and all the apparent chaos is carefully studied and defined: sushi restaurants within the block, food stalls opening to the main road, tiny units rented from the local shrine. One coffee shop rents out two areas within its small ground floor to tuna retailers hoping to benefit from passing trade.

Outer market: sketches. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

These more recent purpose-made buildings incorporate back corridors with servant spaces to prepare food, and offices above. They indicate the gradual shift from the Nihonbashi era, when the market constituted both workplace and residential community, to the Tsukiji era, in which the two have become increasingly separated: whereas at first the Tsukiji neighbourhood became home to many traders and families, as land values increased many were forced to move further afield and commute to the market.

The seven auction houses have their offices in the curved buildings of the inner market. Intermediate wholesalers finish their books after the morning’s trading finishes, around lunch time. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

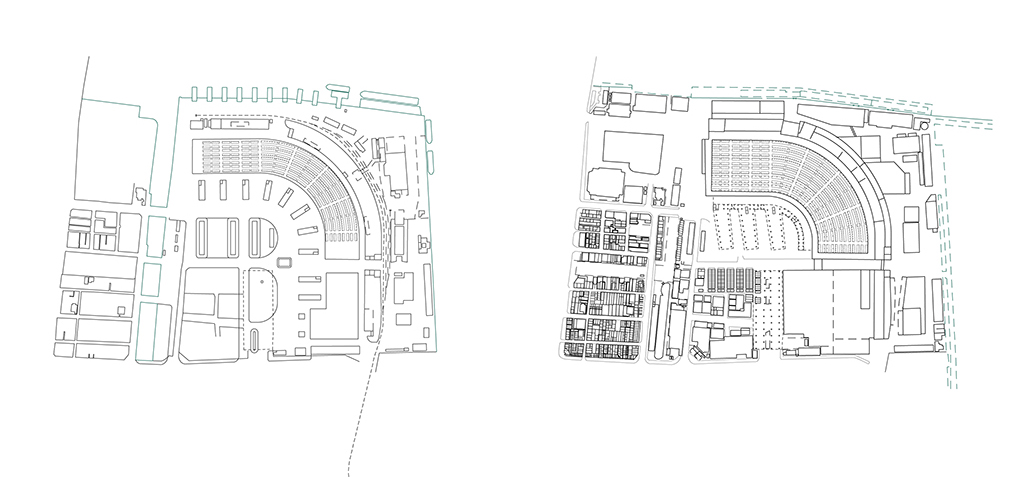

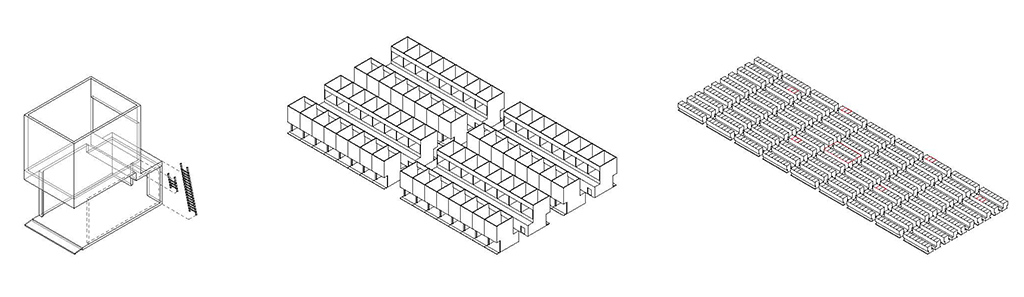

Toyosu proposals: typical stall layout. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

The relocation to Toyosu represents the erosion of market workers’s ability to pursue an occupation situated within an all-embracing social world. Although some of the positive aspects of the current market buildings appear to remain in these outline proposals for the new inner market buildings at Toyosu (for example the abundant storage space seen in the image above), the rigid concrete shells will make for an altogether different kind of occupation.

The requirement for intensified refrigeration and total air conditioning will increase rental prices significantly, and relocation will therefore have different consequences for different types of traders. While larger wholesalers supplying restaurant chains or supermarkets may be relatively unscathed, the move will gravely affect those smaller traders supplying local restaurants and shopkeepers, for whom economies of scale do not enter in and adjacency plays a key role in the development of social ties and the elimination of transport costs.

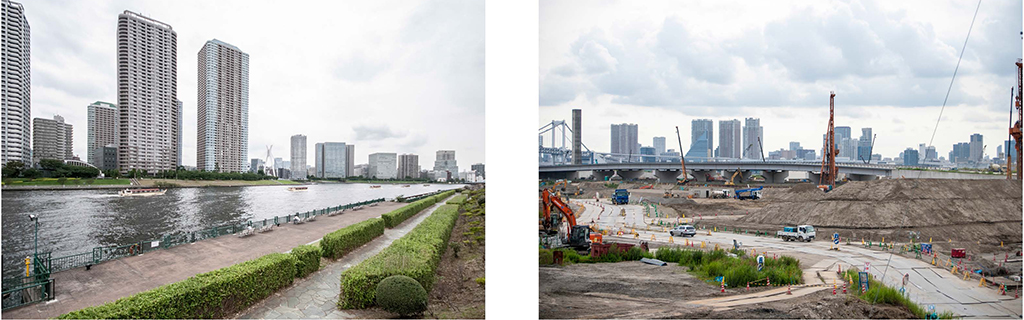

Focus on Tokyo’s waterfront has returned since the 1980s. Recent developments on the reclaimed islands between Tsukiji and Toyosu have been fairly well handled but are lacking in character—you wouldn’t suspect that this view (above left) is from Tsukudajima, once the fabled home to the community of fishermen that came to Edo with Tokugawa Ieyasu and founded the original Uogashi (“fish quay”) at Nihonbashi. Above right: Toyosu building site. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

Inner market: selected case study stalls. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

Some of the inner market stallholders have had businesses in the family for 200 years. According to them, most businesses have been shrinking in recent years, losing out to bigger companies and supermarkets. But these, they claim, don’t have mekiki (the experience and eyes for good quality produce).

In some senses Tsukiji’s relocation is long overdue. Many of the world’s famous food markets were swept away in the 1970s and ’80s, by which time their role in feeding the city had already come to an end. Tsukiji’s primacy as a wholesale market was at its peak in the late 1980s and has been in decline in that capacity since, due to the gradual rise of supermarket culture and online buying.

The shift from a functional center of exchange towards a kind of city spectacle for both locals and tourists has been underway for some time, with visitor numbers rising so high in recent years that they have started to impede the wholesale market’s smooth operation. Tsukiji’s potential as cultural commodity is not lost on Tokyo’s governor: a new building is planned adjacent to the existing site for the Tsukiji New Market with a smaller contingent of market stalls and a multi-purpose public hall. The plan includes “observation areas,” a concrete architectural corollary of such a move towards market as spectacle.

Inner market: tuck shop and market shrine. Credit: Alice Colverd and Alexander McLean.

Interspersed throughout the market are myriad ancillary functions including a bank, two post offices, a barber shop, pharmacy, library, book store, medical and dental clinics, several coffee shops and cafeterias, offices for wire services and trade newspapers, and a hotel. Tsukiji is thus an almost entirely self-sustaining market complex, a kind of micro-urban condition.

Tsukiji therefore presents a model entirely different to many contemporary mixed-use developments in Tokyo and elsewhere. It is an extensively heterogeneous piece of city that has grown over many decades, still changing and operating according to various systems, themselves in constant flux. At a time when many of us are desperately trying to regain a connection with our food and where it comes from, Tsukiji is an important case study for an ancient but disappearing paradigm: the open and visible exchange of the market as fundamental to the idea of what a city is.

Biographies

lived in Tokyo until the age of twelve. She received her undergraduate degree in Architecture from the University of Cambridge in 2010, where she was awarded the RIBA Eastern Region Prize. She has since worked at Kazuyo Sejima + Ryue Nishizawa / S A N A A in Tokyo, and at Feilden Fowles and 6a architects in London. She received the Kate Neal Kinley Memorial Fellowship in 2012 and is currently pursuing her architectural education at The Cooper Union in New York.

was born in London and completed his undergraduate degree in Architecture at the University of Cambridge. In London he joined 6a architects, and formed part of the design collective Assemble, constructing self-built public projects around the city. Undergraduate research into the role of traditional religious festivals in the Japanese urban environment brought him to Kyoto, Osaka and Niigata in 2009. Alexander has since moved to New York to complete his architectural training at The Cooper Union.

Explore

A Guadalajaran perspective on the future of Mexican architecture

Regional Mexican design is having a moment, says Luis Aldrete, but the nation's rapid change makes the next steps hard to predict.

The simplest move for the biggest impact

An interview with SPORTS, winners of the 2017 League Prize.

Interview: graciastudio

An interview with Jorge Gracia of graciastudio, as well as a video of his lecture, and a slideshow of the firm's projects.