Rethinking Dharavi: An analysis of redevelopment programs for slums in Mumbai, India

Abigail Ransmeier writes about the successes and shortcomings of slum redevelopment programs in Mumbai.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Abigail Ransmeier received a 2001 award.

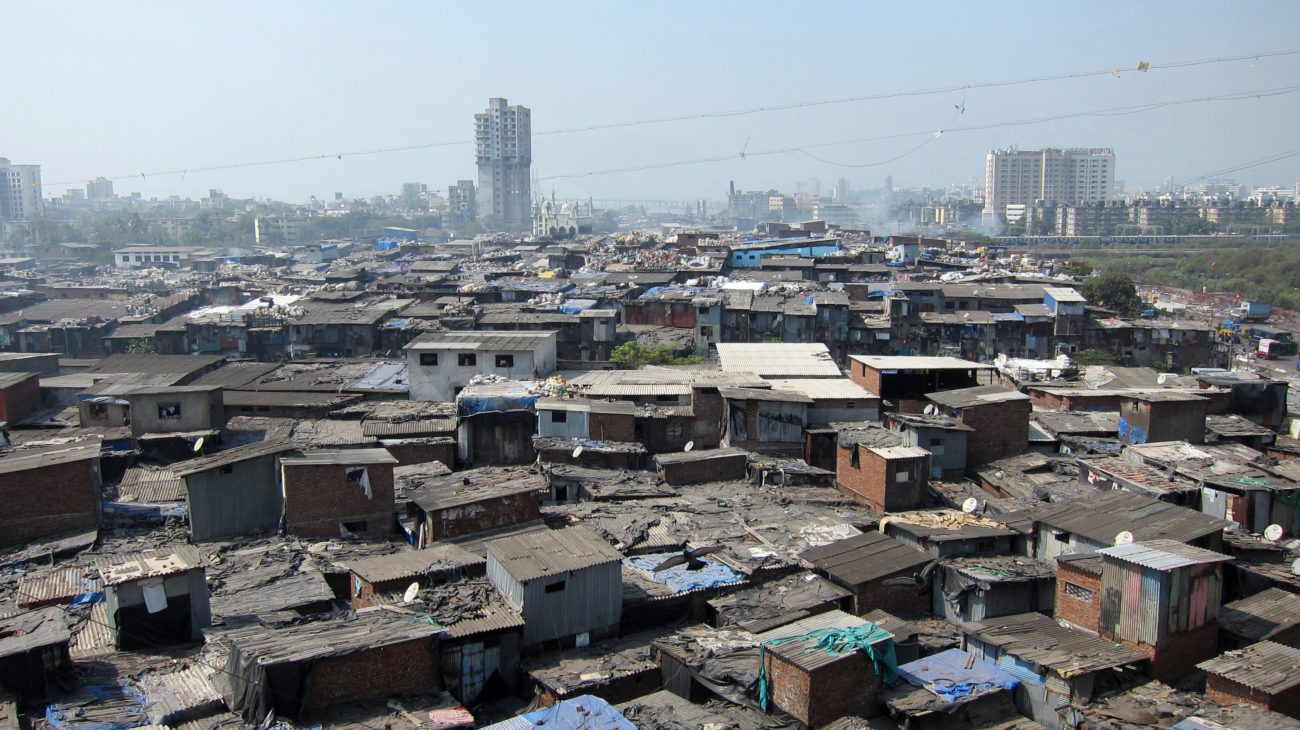

Dharavi is Mumbai’s largest slum. There, nearly one million people inhabit low-lying structures erected haphazardly on four hundred acres of former swampland. For more than three centuries, this waterlogged district existed at the outskirts of the city, an undesirable stretch where only Mumbai’s poorest and newest residents made their homes. Over time, Dharavi’s relative location has shifted. Today, this unplanned, poorly-serviced tract sits strategically between the city’s two commuter lines and adjacent to the Bandra Kurla Complex, Mumbai’s new corporate hub. Land that was once deemed undesirable suddenly claims a valuable, even vital position, and parties that ignored Dharavi for over a century now show a determined interest in its rehabilitation.

In 1995, in an effort to reinvigorate key slum areas, The Maharashtra Housing and Urban Development Authority (MHADA) established the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) and enacted Mumbai’s current Slum Rehabilitation Scheme (SRS). The SRS makes innovative use of land as a resource, offering free land and financial incentives to private real estate developers who agree to rehabilitate existing slums. This free land subsidizes the development of fully-serviced Western-style apartment blocks comprised of 225 square foot self-contained housing units. The units are made available at no cost to slum dwellers who can prove that they have lived in Mumbai since before January 1, 1995.

But while the MHADA may have good intentions, the SRS falls short. By encouraging high-rise residential developments, the SRS creates a built environment that is incompatible with the lifestyles of Dharavi’s current inhabitants. To rehabilitate in a more sensitive way, planners ought to be more flexible and adopt an interdisciplinary approach that better negotiates Dharavi’s complex physical and economic condition.

Dharavi’s landscape

After India’s independence in 1947, Mumbai’s squatter population soared. City officials now estimate that 63 percent of the city’s current population (measured just shy of sixteen million) live in slums, on pavements or along railway tracks. This population occupies only eight percent of the city’s total land, area creating densities of up to eighteen thousand persons per square kilometer.

Dharavi’s unplanned streets attract migrants from every region of India. Potters from Gujurat, Muslim tanners from Tamil Nadu and embroidery workers from Uttar Pradesh occupy closely-knit settlements jammed one beside the next. This ethnic diversity fosters Dharavi’s socioeconomic strength. In March 2004, the BBC reported that Dharavi’s markets generate roughly 1 billion dollars per year. Export-quality leather bags, chiki, embroidered shawls and jewelry pop out of illegal workshops and saturate Mumbai’s streets. Only 10 percent of the settlement’s population is unemployed – a small percentage for any Indian suburb, let alone for a slum.

Furthermore, despite their informal planning, Dharavi’s “kutcha” districts offer something that Mumbai’s more formal “pukka” neighborhoods lack. Unlike the residential developments that typify westernized Mumbai – mega-structures standing on super-plots separated by overly-wide roads that foster little sense of community – Dharavi’s settlements operate like small, self-governed neighborhood units. Hutments are arranged along footpaths or in clusters that open onto shared spaces that easily adapt to the settlement’s daily activities. Shrines, workshops and markets are interspersed throughout. At dusk, men congregate to discuss local politics over rounds of chai, and women gather at communal water taps to gossip over piles of laundry and vegetables. The settlement’s maze-like configuration offers a sense of security to its inhabitants. Gateways are barely recognizable, and even the youngest children wander freely within the boundaries of their communities.

Free housing – rehabilitation under the SRS

In 1995, a coalition of the Shiv Sena and the Bharatiya Janata Party assumed power in Mumbai, promising four million units of free housing to eligible slum dwellers. The government’s goal was two-fold: to mitigate Mumbai’s housing crisis and to improve the city’s infrastructure.

A few years later, MHADA asked the architect Mukesh Mehta to create a master plan for Dharavi’s rehabilitation, along the lines of SRS. At the time, Mehta proposed that Dharavi be organized into twelve residential sectors, based on the boundaries of existing slum settlements. He suggested sector-based, phased collaborations between private developers and existing communities, advising that each slum settlement receive an autonomous mixed-cooperative housing facility comprised of 225 square foot residential units complete with private kitchen, toilet and wash closet facilities.

His plan placed commercial units on ground floors with residential units above them, and included community workshops, health centers, day cares, and open space, to ensure a sense of community at all SRS facilities.

Since the fall of 2001, several densely packed slum societies have been collaborating with Mehta on housing complexes. While most slum dwellers are eager to relocate to new Western-style apartment complexes, others are concerned. Thus far, SRS buildings have provided only a limited number of ground floor commercial lots. Slum dwellers wonder: can barbers and shoe repairmen, seamstresses and pan bidi stalls – small businesses that barely subsisted with ample foot traffic – survive if they relocate to the tenth story of a high-rise apartment complex?

Kumbharwada is one slum community facing this conflict. Occupying twelve acres of prime real estate at the intersection of two of Dharavi’s most prominent roads, Kumbharwada is one of Dharavi’s poorest communities. The Kumbhars specialize in making pots, a craft they brought with them from their homeland in Kutch. Their traditional potting methods mandate specific spatial arrangements. Women tend to their homes and to their kilns, integrating their pottery activities with child-rearing and household chores. This unique way of life makes relocation to the proposed SRS buildings impractical. Moreover, the Kumbhar’s existing slum huts are larger than the 225 square-foot apartments that the SRS promises, yet they house twice as many people as smaller huts do in typical slums. Since the SRS allots free apartments based on the number of existing huts and not on the number of people who live in them, the Kumbhar’s free apartment quota does not accommodate the community’s most basic residential needs, let alone their kilns.

In November 2001, Bombay’s Principal Secretary of Urban Development, Mr. A. P. Sinha addressed local officials and non-governmental organizations in a talk entitled “Work Plan for Cities Without Slums.” In his address, he demanded a “cafeteria approach” to rehabilitating Dharavi. Sinha’s call for a variety of responses represents a constructive step forward. It recognizes that the SRS housing blocks offer logical solutions for some slum populations, but not for all. For example, a temporary site and services model might suit the transient needs of migrant workers. Some Kumbhars say that they would share toilet and cooking facilities if it would free funds for improved kilns. Slum women have suggested that kitchen walls and counters should be removed from SRS units since women like to cook communally while seated on the floor. More affluent slum dwellers in Dharavi even say that they would like to pay extra for larger apartments with layouts more suited to their lifestyles.

It is clear that Dharavi is poised for change. Its unique geographic position and socioeconomic makeup demans new building typologies. While it is undeniably operative, Dharavi would offer more to Mumbai, as well as to its own inhabitants, if it better integrated its current residential and commercial requirements with its existing recreational and ceremonial functions. Mumbai’s challenge, therefore, is to employ a rehabilitative approach that reinvigorates Dharavi’s buildings and infrastructure, while respecting its industrious nature and communal social patterns.

Biographies

traveled to India in 2001. She returned eager to become an architect, and is currently in her third year at Yale School of Architecture, where she continues to combine interests in international development and architecture. She recently received a fellowship from the Yale Center for International and Area Studies to complete a schematic design for mixed-use, low-cost housing in Mumbai. In August 2006, she will begin work at Behnisch Architekten in Stuttgart, Germany.

Explore

Rahul Mehrotra: Working in Mumbai

Rahul Mehotra discusses his research and design practice.

Arverne: Housing on the Edge

A 2001 exhibition considering four proposals for the Arverne Urban Renewal Area on the Rockaway peninsula in Queens.

A Parallel History

In an introduction to 1977 book Women in American Architecture, Susana Torre considers cultural assumptions about women as consumers, producers, critics, and creators of space.