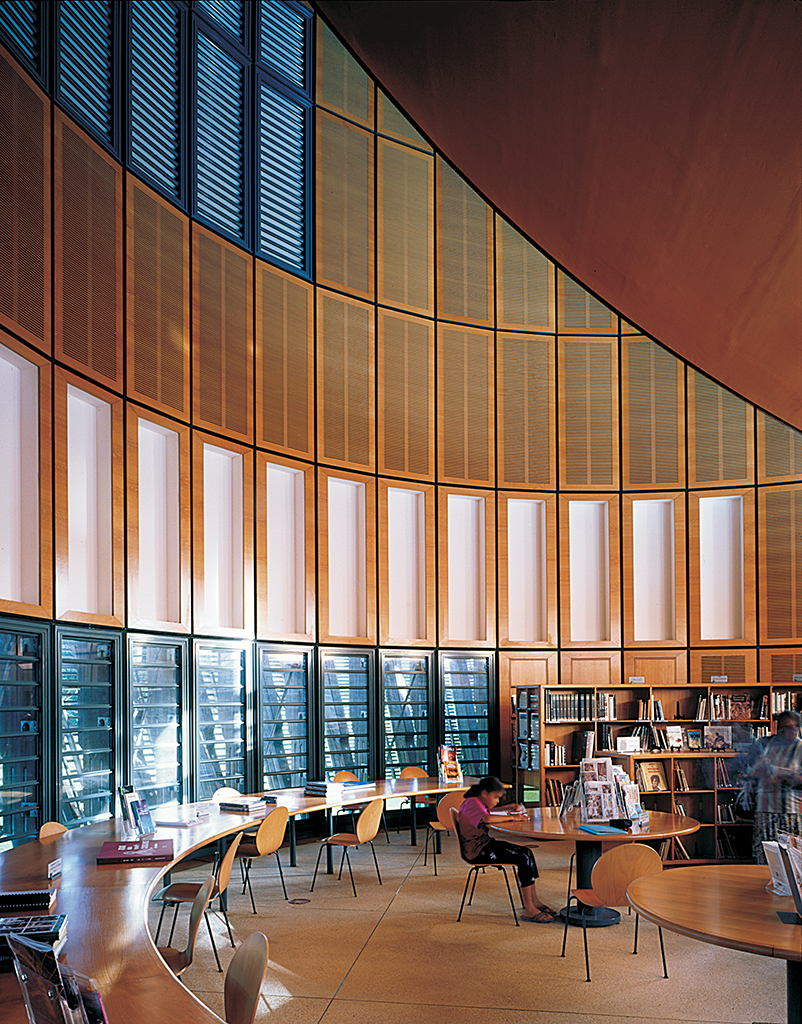

Jean-Marie-Tjibaou Cultural Center, New Caledonia | photo: John Gollings, courtesy of RPBW

J.M. Tjibau Cultural Center

Of all current projects by the Building Workshop, this cultural center for the Kanak people of New Caledonia seems especially to touch some common nerve and thrill almost everybody, architects and lay people. Perhaps it is the image the competition-winning design projected of huts and hamlets nestling among the pines and palms of a Pacific island promontory that people respond to. Certainly it suggests some South Sea island fantasy.

The enclosed parts of this initial design are like capsules of imported high-technology materials and equipment. These are partially wrapped by tall apses of laminated timber that are clad with periodically renewed bark strip and palm fronds. Resembling the traditional Kanak huts, these vegetal husks mediate between the kernels of enclosed space and both the natural setting and the traditional man-made settlements. The concept is almost analogous to a modern man complete with Walkman, shades and sun-block going native in a grass skirt. No wonder Piano himself is nervous about the design, despite its enthusiastic reception, and is guiding it through a lot of changes.

Jean-Marie-Tjibaou Cultural Center, New Caledonia | photo: Michel Denancé, courtesy of RPBW

For all its exoticism, the design does have roots in earlier work by the Building Workshop. Wrapping the high-technology enclosures in a camouflaging contextual overcoat, here the vegetal apses, has its precedents in the clapboarding of The Menil Collection and the terra cotta elements of the IRCAM extension, although these lack what some may see as the excessive and redundant flourish of the apses. The intention of involving the local people in the periodic communal replacement of the bark strip and palm frond cladding of the apses, as they ritually did with their traditional homes, recalls the participation exercises of the UNESCO reconstruction projects and the Corciano housing. And the rich mix of materials, in particular the sculpted, laminated wood vertical members of the apses with their cast aluminum footings, is reminiscent of the IBM travelling pavilion.

In the competition-winning design the apses were tall and their vertical members met at the top as they do in Kanak huts. It was intended that these serve to scoop wind down and into the interior, or guide convection air out of it with the aid of the Venturi effect. Wind tunnel testing and computer modeling of structural performance have led to modifications to the form of the apses so that the vertical members no longer meet, though the apses remain wonderfully evocative in form. In the latest scheme the roof behind it no longer swoops up in a curve into the apse, but steps upwards into it. And the walls have changed from metal panels to modest blockwork. The design is inevitably becoming more pragmatic, and more in keeping with the limits of local construction technology and maintenance.

Jean-Marie-Tjibaou Cultural Center, New Caledonia | photo: William Vassal, courtesy of RPBW

Where this scheme will finally evolve is not sure. Though there is a certain excessiveness to the design, enclosed areas for instance are small in relation to constructed volume which includes covered ways and the apses that have little real functional justification, it would be a great shame if the building lost these elements. So much of its appeal and generosity of spirit depends on them. Besides, once proposed, they almost seem to have a will of their own to come into being. Perhaps Piano has to take courage and go with the irrational elements of this scheme, accepting that they have their own value in the suggestive connections they make with tradition, climate and surrounding vegetable kingdom.

Padre Pio Pilgrimage Church, San Giovanni Rotondo | photo: Michel Denancé, courtesy of RPBW

•••

Padre Pio pilgrimage church

This still evolving design is the last to which Peter Rice contributed in its initial stages. He was largely responsible for the decision to use stone arches, having been as interested in exploring new potentials in old materials as those of new and as yet untried ones. The precision cutting now possible with stone ensures an even distribution of stresses and so more predictable performance. These combined with new understandings of arch action and the number-crunching capacities of the computer — so that arches can be calculated as an infinity of hinges instead of in terms of thrust action — might give new life to stone as a structural rather than mere cladding material.

Rice had already explored stone in the arched gateway to the Seville Expo that he had designed with the Barcelona architects Martorell Bohigas Mackay. There the arches are very tall and the granite colonettes so slender as to be the envy of any Gothic mason. But the structure is too virtuoso: the visual effect is so insubstantial that the gate has little presence and the viewer does not register and so thrill to the fact that this precarious poise is achieved in stone, not some light and ersatz material. Padre Pio will be quite different. Here the funicular arches, that will span 167 feet (a little more than the diameter of the drum of St. Peter’s) will be fairly flat and made of huge and obviously heavy blocks. They are bound to have a powerful and archaic presence.

Padre Pio Pilgrimage Church, San Giovanni Rotondo | photo: Michel Denancé, courtesy of RPBW

The heaviness of these arches seems to contradict Piano’s persistent quest for lightness. Yet this will come from the system of timber props and thin steel stays that reach out from the arches to support the copper clad timber dome. All these will float in a chiaroscuro that will contribute to their sense of lightness and by contrast, to the grave massiveness of the arches.

The design is also an exercise in crowd control, of the pilgrims and the buses that clog most such sites. Buses will be parked either side of a road that leads up to the tall belfry-end of the retaining wall of the piazza that serves an outdoor overflow auditorium for feast-day congregations. As at Assisi this wall, rather than the here tree-hidden church, will guide pilgrims walking towards it and then up along it to the apex of the piazza and the monastery church where Padre Pio preached. The slope of the piazza will itself tilt pilgrims towards the church and into the seating on its dished floor.

As with so many Building Workshop designs, this one might seem an anomaly, unlike anything they have done before. As another huge domed roof, the Ravenna sports hall might be seen as a precedent. But Ravenna, like the domes of Pier Luigi Nervi, is to be made of a single Modern material, ribbed concrete. In the way it mixes traditional materials, Padre Pio is an antithesis of Ravenna and a modern Italian tradition.

Padre Pio Pilgrimage Church, San Giovanni Rotondo | photo: Michel Denancé, courtesy of RPBW

The design is still far from developed. The domed roof probably floats too high above and dwarfs the arches. Kenny Fraser, the architect working on it, anticipates that the dome will lose its pudding-like quality as segments between the outer ring of arches are left unroofed and unenclosed. This will allow planting to seem to enter the apse of the church and so to interweave architecture and nature. It will also create pockets within the vast space that are suited to smaller congregations such as weddings, with adjacent gardens to be used as part of the event. This also makes more sense of wrapping the church in trees.

The text below was originally published in the exhibition catalogue for the 1992 Architectural League exhibition Renzo Piano Building Workshop: Selected Projects. All text by Peter Buchanan, © The Architectural League of New York.

Previous: Part 7: Projects: UNESCO laboratory workshop & Kansai International airport

Explore

April 9, 2013

Renzo Piano

On April 9, 2013, The Architectural League presented its President’s Medal to Renzo Piano.

December 18, 1992—January 30, 1993

Renzo Piano Building Workshop: Selected Projects

An exhibition presented by The Architectural League of New York and the Italian Cultural Institute.

December 4, 2017

Global culture, civic competition, social impact

A discussion with Arthur Cohen, Adrian Ellis, Victoria Newhouse, Joshua Prince-Ramus, and Annabelle Selldorf.