The Plecnik projects: Public experience and the section of water

Kerry O’Connor writes about infrastructural public works by architect Jože Plečnik along two rivers in Ljubljana, Slovenia.

July 8, 2014

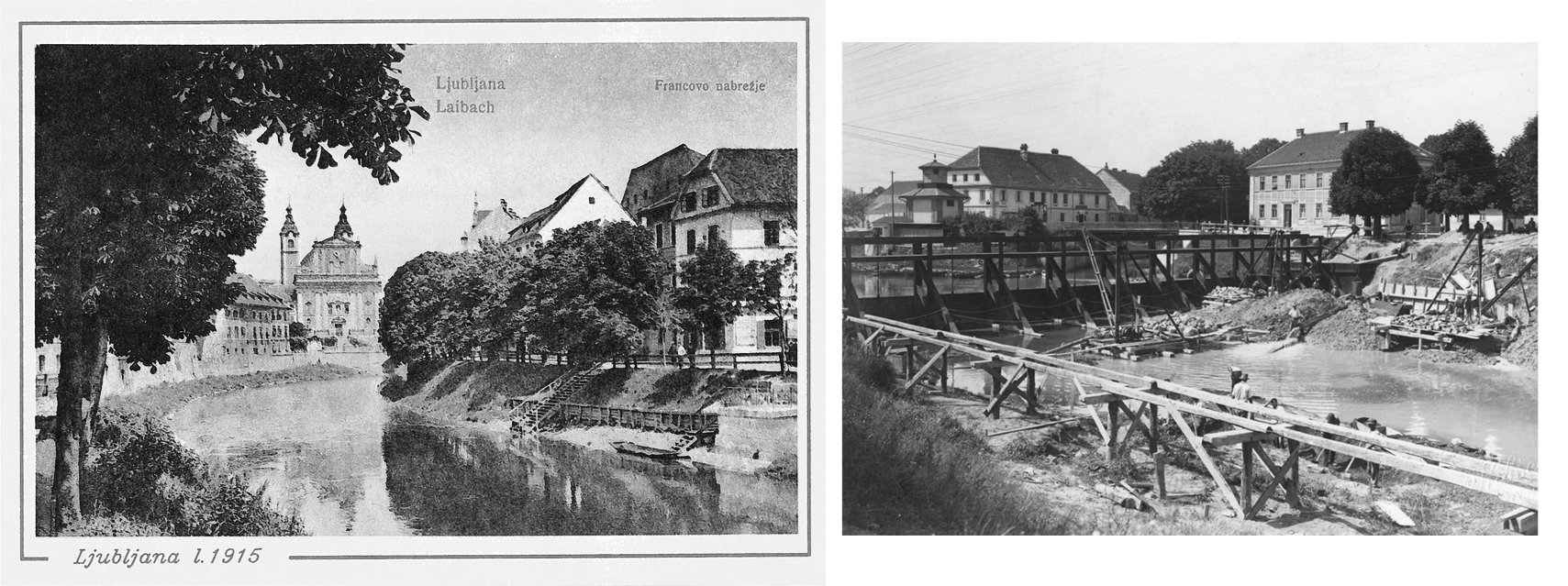

Left - Postcard showing existing conditions of the Ljubljanica in 1915 Right - Construction of the banks of the Gradaščica in 1931 (MGML Archives)

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Kerry O’Connor, the winner of a 2014 award, wrote this report about his findings.

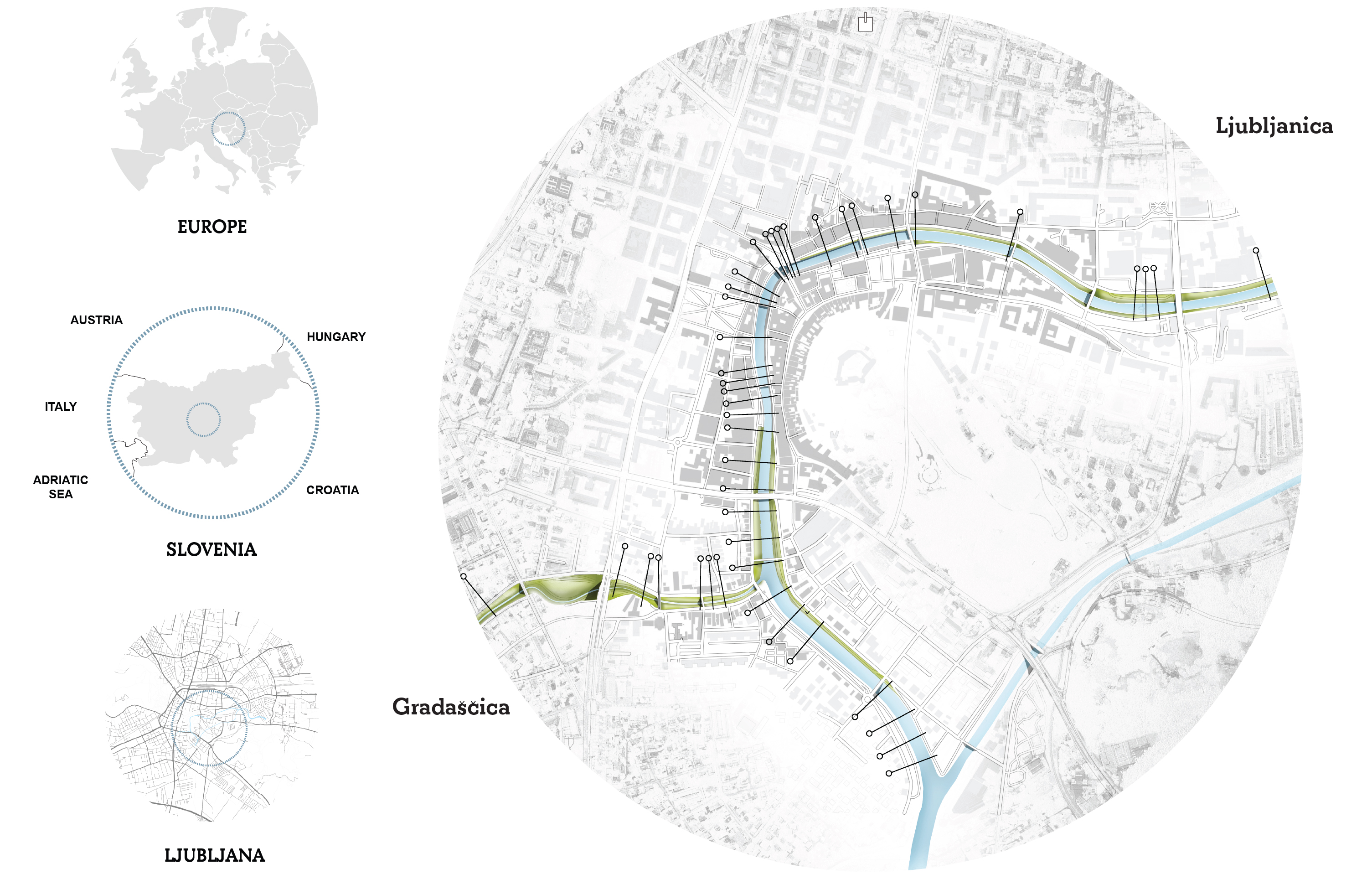

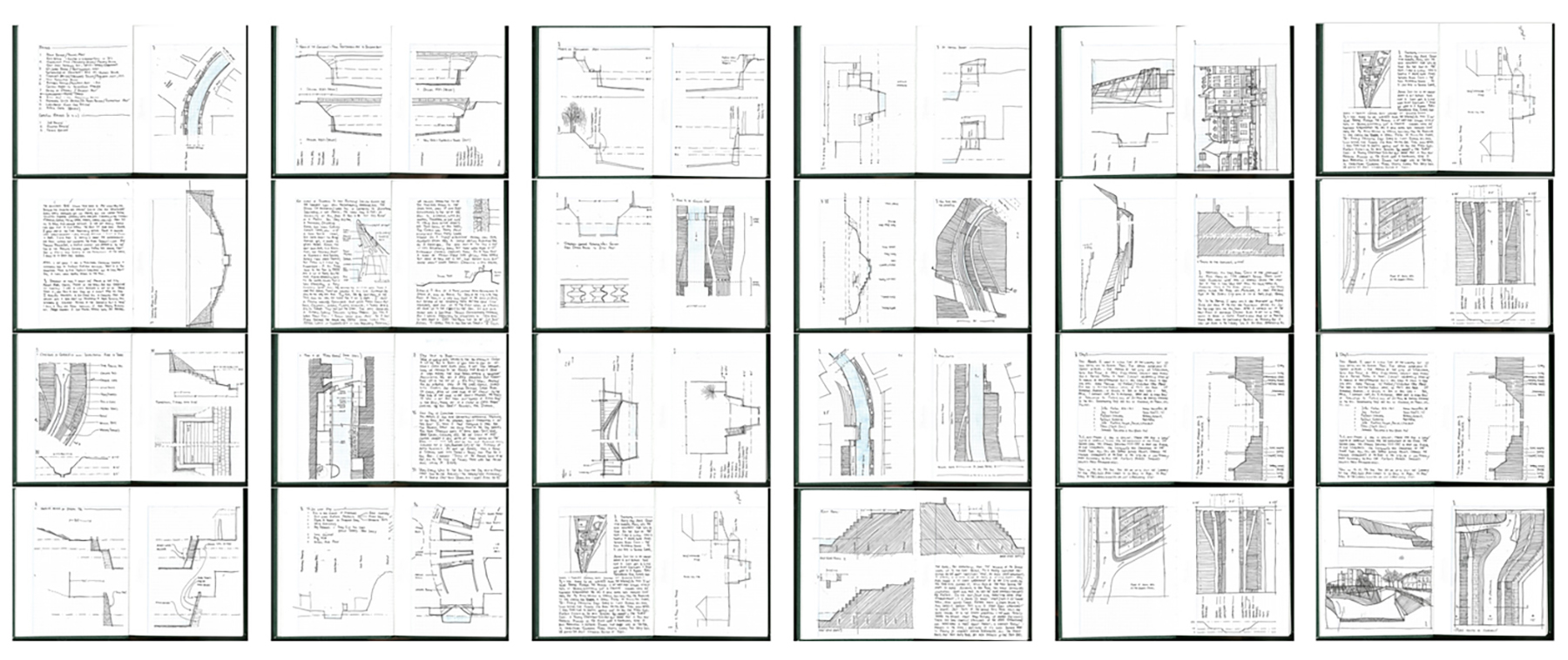

In September 2014, I travelled to Ljubljana, Slovenia to study a two-and-a-half mile sequence of infrastructural public works along the Ljubljanica and Gradaščica rivers by twentieth century architect architect Jože Plečnik. Plečnik’s interventions in Ljubljana represent an operative encyclopedia of methodologies for leveraging the spatial characteristics and functional demands of water to design a continuously varied and fantastically dynamic urban experience at the interface of the river and the city. Over the course of two weeks I sketched a sequence of measured of sectional conditions as I followed the two rivers from a rural condition to the city center and back out to the countryside while simultaneously mapping the contextual, topographical, and situational provocations of the adjacent neighborhoods. Joze Plečnik’s design strategies – visionary at the time – anticipated a performatively resilient and programmatically rich approach to designing the edge of water.

Brimming with symbolic ornamentation and historical reference, Jože Plečnik’s architectural work during the first half of the twentieth century was seemingly out-of-sync with the social and cultural imperatives prevalent in the architecture of his time. Later, his interest in the vernacular imagery of native Slovenia (then Yugoslavia) and idiosyncratic building style were sources of reference for early postmodernists. Early surveys of his work largely overlook Plečnik’s large-scale but formally restrained public works executed over the course of decades in parallel with his stylistically-exuberant architectural projects. Ironically, Plečnik’s inhabitable sections and multi-functional, programmatically varied infrastructural systems – not dissimilar in concept from utopias like Le Corbusier’s Plan Obus for Algiers or Tange’s plan for Tokyo Bay – demonstrate a synchronicity with the forward-thinking visions of his modernist contemporaries.

In the early 1930’s Plečnik rapidly developed, in collaboration with the city’s public works department, plans for the revitalization of two rivers which traverse the urban core of Ljubljana. These plans were part of a larger effort by Plečnik to revitalize Ljubljana by identifying key areas – arterial roads, squares, and bridges – in need of renovation. In the interwar period he was the de facto architect of the city, and was able to execute large-scale urban improvements by working closely with the municipal engineer Matko Prelovšek, translating conceptual sketch drawings into built work at a rapid pace.

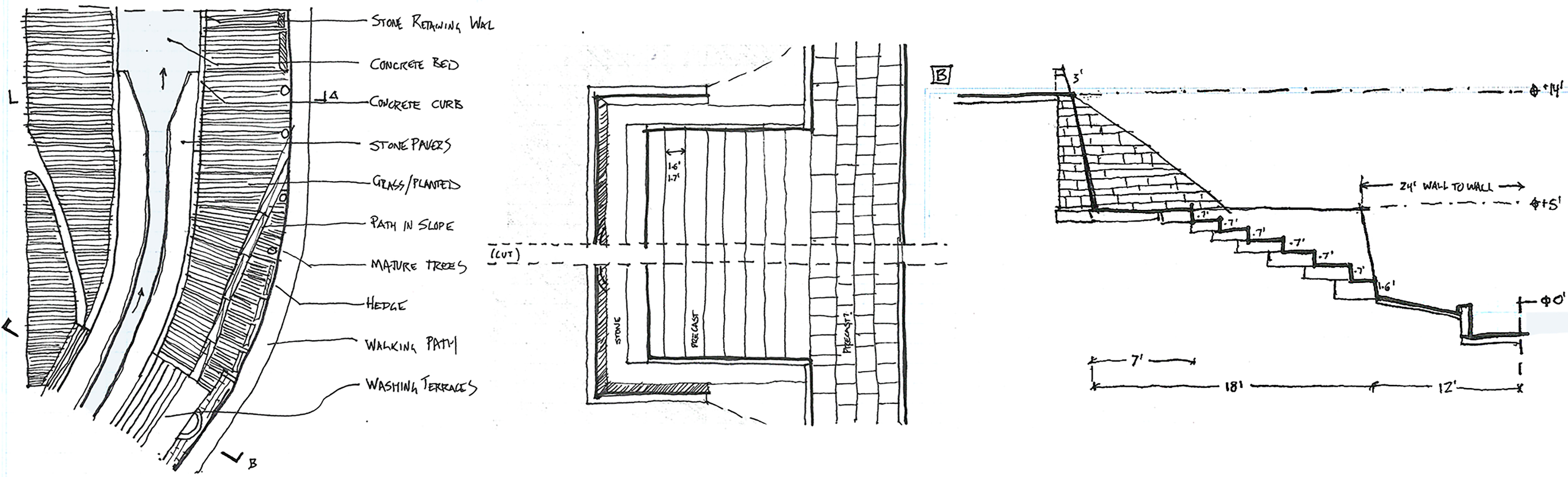

The river project itself was a bit of deferred maintenance after a 19th century dredging project, and by the time Plečnik got involved, the concept of the concrete embankment was already a foregone conclusion. The beginnings of his involvement saw him proposing flourishes to the engineered plan; eventually he became more deeply involved in coordinating the design of the edge. Plečnik worked to identify strategies – linkages, occupiable thresholds, engineered walls, and soft edges – that could incorporate or accommodate the inevitable cycles of flooding all while redefining space around the water’s edge to provide open access for the citizens of Ljubljana.

During the trip, I spent about a week studying the Ljubljanica, the larger of the two rivers, which cuts across the grain of the city in its center. Along the Ljubljanica, the design of the river embankments is closely synced with the relative level of density of adjacent neighborhoods. At the suburban southern end of the city, the river is depressed fifteen to twenty feet from the adjacent grade and the banks take the character of a shaded promenade or linear park with descending paths and shortcut stairs for pedestrian access at intersections. Immediately adjacent to the water, a highly articulated, stepped stone edge provides terraced seating and demarks the relative height of the river. Sloping, planted berms provide sectional separation and reinforce the idea of an outdoor room within the city. Plečnik’s landscape design – most notable here for its linear arrangement of willow trees – acts to frame the space in these rooms and to delineate distinct precincts.

Stepped stone edge introduces terraced seating at the Ljubljanica and demarks water levels. Credit: Kerry O’Connor

Further north, in the city center, the embankments are constructed as a high, hard-edged channel. Here, the section develops a more overtly architectural character, where inhabitable indoor and outdoor spaces at an intermediate level are carved out of an otherwise infrastructural monolith. Simultaneously a series of lush terraced landscape planters built into the embankment support giant poplars and a lushly planted landscape.

Plečnik first began working on the waterfront in the late 1920’s with a series of elaborate bridge projects, most notably at Tromostovje (Triple Bridge), an expansion of a vital crossing that linked the medieval historic city to an emerging modern business district. Plečnik’s primary bridges, all nearly as wide as they are long, function as urban plazas, reclaiming area in the densest parts of the city for commerce, promenade, and performance. Where the Triple Bridge meets Plečnik’s Central Market project (1940’s), the notion of a ground plane is subverted completely as stairs to an intermediate level fold down from the pedestrian footbridge to give access to a new lower mezzanine. Here at the city center, the multi-level market, both indoor and outdoor, is itself the embankment.

At the eastern edge of the city, high concrete embankments give way to a hybrid concrete-and-berm approach, culminating in Plečnik’s Monumental Sluice Gate. Miles out, the Ljubljana re-exerts itself as a low, wide, meandering river.

Plečnik’s Sluice Gate marks the eastern entry to the city. Miles east, the Ljubljanica takes on a more natural formation. Credit: Kerry O’Connor

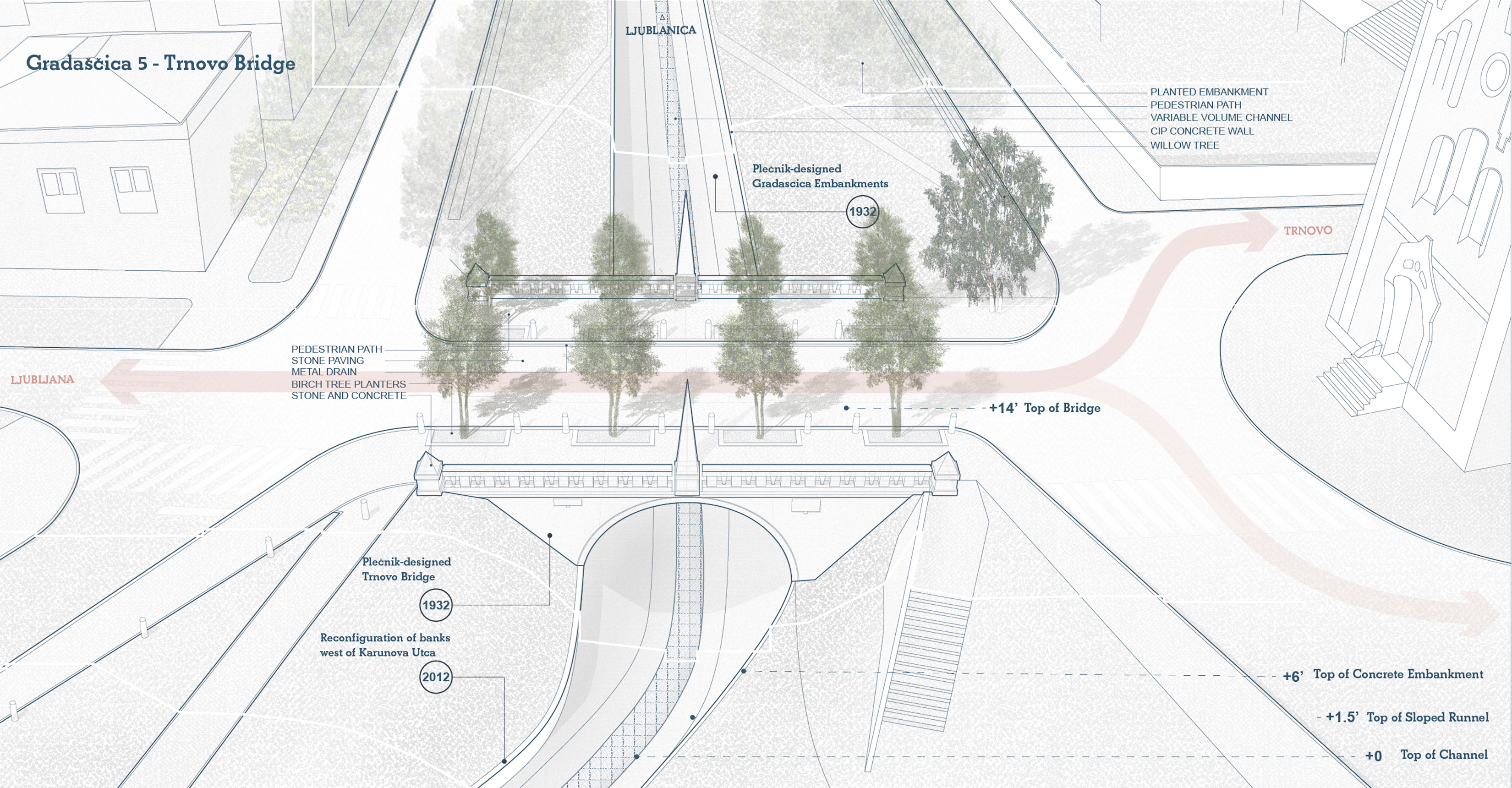

Plečnik’s interventions in the city are experienced as a narrative sequence, where distances are linked by visual markers, large-scale iconography gives meter to a walkable city, and widened or otherwise distinguished ground planes create new primary corridors. Nowhere is this more true than along the Gradaščica, which flows west-to-east and empties into the Ljubljanica. As it enters the city from the west, the river flows in a symmetrical channeled condition into the Trnovo district where steeply sloping banks are retained by a concrete wall and the river banks themselves are laid with stone. Over the deep crevice of the Gradaščica, Plečnik designed a new crossing – the monumental Trnovo bridge, marking the entry to the district. The bridge is a wide planted platform, itself an extension of the urban grade.

Trnovo bridge is a broad concrete platform clad in stone and densely planted with birch trees. The bridge extends the ground plane and locally caps the Gradaščica to create a new public space on axis with a the historic church of John the Baptist. Credit: Kerry O’Connor

In Trnovo, a primarily residential suburb, Plečnik introduced steeply sloping paths in the the bermed earth to give access down to the water, and at the edge, a shallowly sloping bank accommodates storm surges. Further east just before the Gradaščica empties into the Ljubljanica, Plečnik inserted a retaining wall and a series of wide steps as laundry washing terraces.

Urban plan

Over the course of the two weeks in Ljubljana, I stayed in three apartments in different neighborhoods along either bank of the river and got a sense of the way the river acts as an organizing and orienting element in the city. Access and exit points to the river promenade are calibrated to the cross-grain of the neighborhood streets: the river projects constitute a linear park but the system is clearly calibrated to operate transversely, connecting adjacent neighborhoods and binding otherwise bifurcated precincts along a meandering central spine.

In his master plan and in the construction of the embankments, Plečnik identified locations for future bridge connections, and in the time since, beginning in the 1950’s and continuing through to the present, designers have continued to develop the embankment projects. There are a number of renovation projects planned or underway, so this was an ideal transitional moment to capture the original projects with a half-century of weathering prior to renovation. Plečnik’s approach to designing the edge sets up an open-endedness to the projects that both accommodates future developments and suggests a sectional vocabulary for their implementation by a newer generation of Slovenian designers.

There is nothing in his archives to suggest that Plečnik had a progressive ecological agenda, but his pragmatic design approach was one that inherently addressed not only the operative requirements of these systems to contain, control, and deliver the water through the city but their ability to contribute to civic life in the capital. Given the performative mandate of water management in surge-prone cities and the seemingly paradoxical trend toward waterfront urbanism, his work at the rivers in Ljubljana, long neglected, is now more relevant than ever. Mega-scale projects by their nature alter their contexts; the most effective infrastructures are those that are multivalent and can activate further transformations that enhance urban life.

Biographies

Kerry O’Connor, the 2014 recipient of the Architectural League Norden Norden Prize, is an architect in New York. Born in Hornell, NY, he earned a Master of Architecture from Washington University in St. Louis, where he graduated with honors, was a finalist for the Widmann Prize, and won the Degree Project Award for outstanding thesis. Kerry received a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Notre Dame.

Explore

Re-reading ornament: Textures in Islamic Spain

Fiyel Levent describes an art and architecture of tolerance from medieval Andalusia.

Arverne rebuilds: Water’s Edge, Arverne-by-the-Sea, and Arverne View

Emily Nathan covers the recent history of Arverne's development and its impact on those who call it home.

Material flows, ecosystem growth, and urban landscape renewal

Paul Mankiewicz explores ways to improve the environmental, infrastructural, and economic health of cities.