Making buildings, making books

For Trattie Davies and Jonathan Toews, book-making has become an important part of architectural practice.

By Sarah Wesseler

When Trattie Davies and Jonathan Toews talk about their work, they can sound more like novelists or filmmakers than architects. The Davies Toews co-founders are fascinated by the personalities, emotions, and idiosyncrasies that reveal themselves during a building project—the messy realities that are swept out of sight for the official photos.

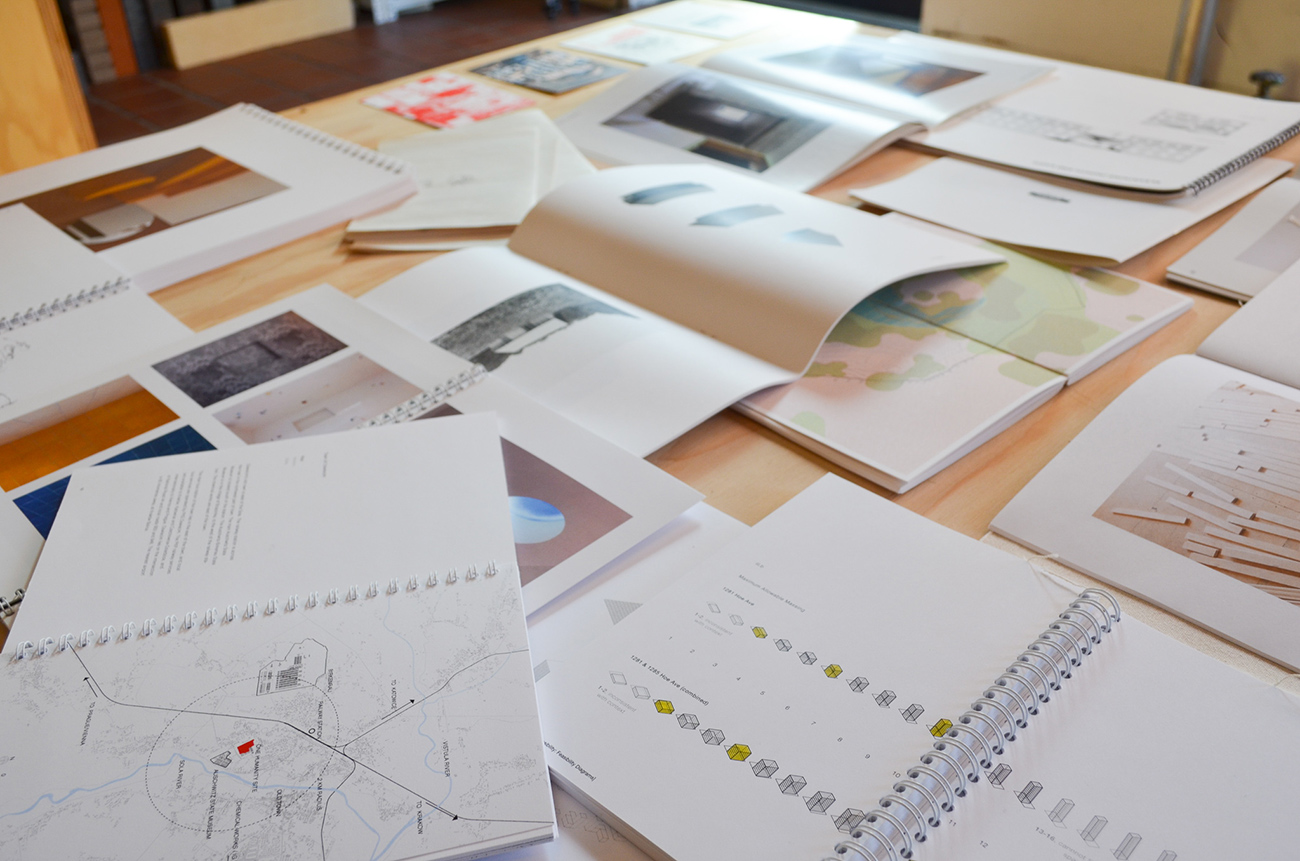

This literary sensibility finds expression in the small books that are part of their regular output. Originally started as a way to send information to a client located outside of the city, book-making has become an important tool for the practice.

At first, the books “were just data,” Davies said. In the early stages of a project, the team would gather information about the site and the client’s needs, creating a kind of reference manual to help guide decisions as the design progressed.

“It’s nice to have to them by your desk and be reminded of the many contexts within which the project is sitting, natural [and otherwise],” Toews said.

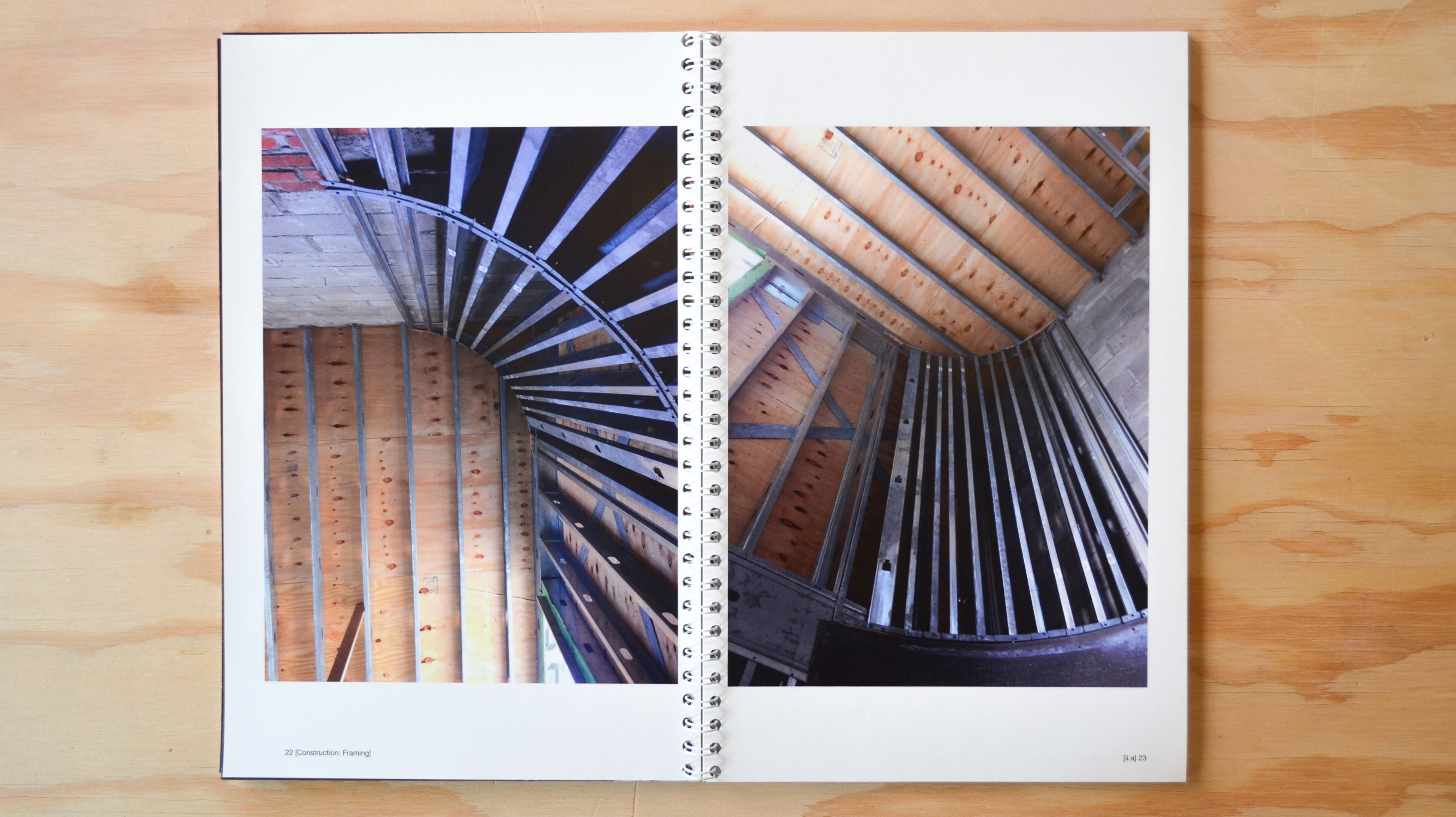

Over time, they’ve taken on a more poetic tone. Some books pull together observations from a construction site—bricks piled haphazardly on the floor after a wall is demolished; electric cords snaking across a floor and ceiling; the changing of the seasons.

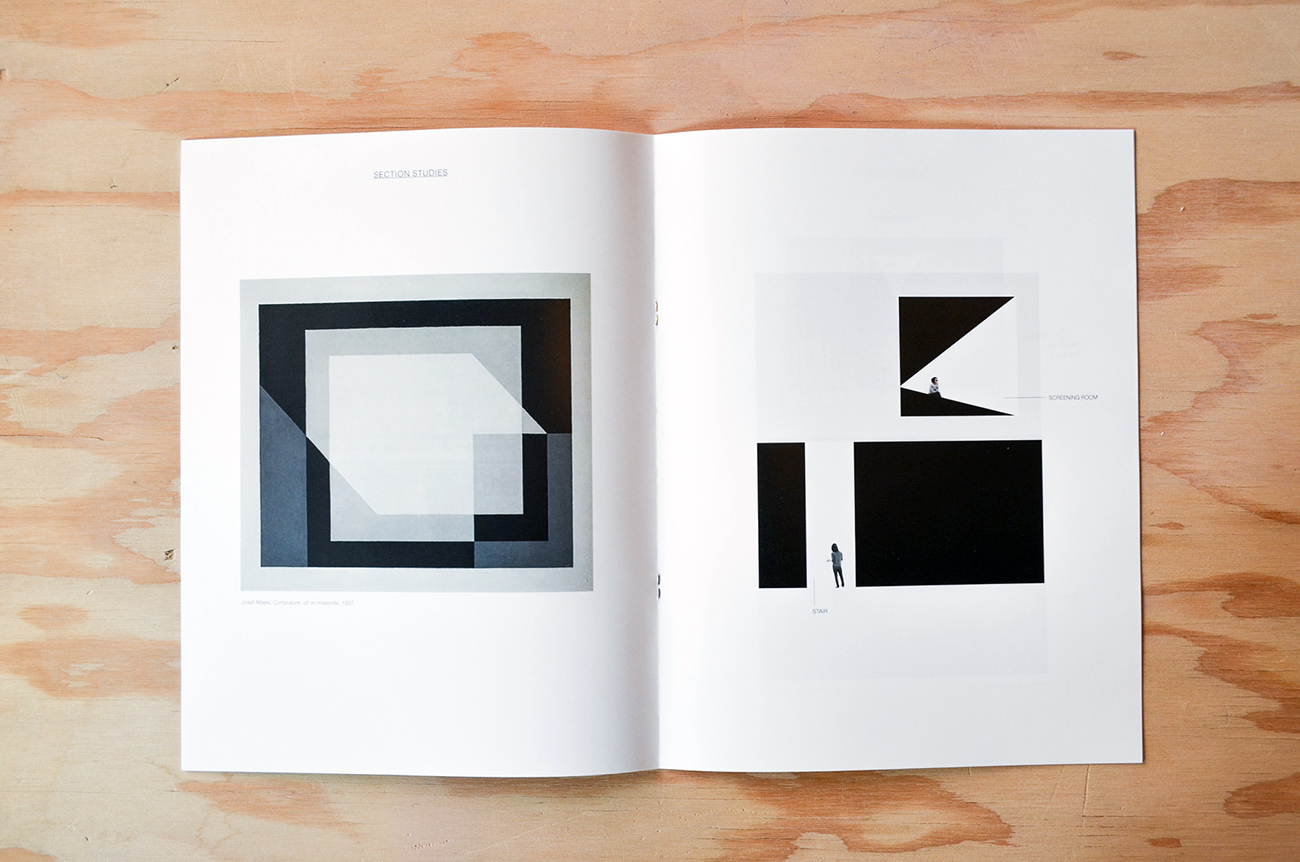

In standard architectural practice, “there’s no room for all these surreal moments that are easy to ignore or discredit,” Davies said. By contrast, she and Toews increasingly believe that paying attention to details like these is an important part of their work. The firm doesn’t have a standard building type, signature style, or ideological agenda; instead of approaching commissions with a big-picture vision and working down to the specifics, it starts by studying the particulars, then builds up from there. And while this necessarily entails careful consideration of context, budget, and program, for Davies and Toews it also means cultivating a heightened awareness for everything that touches a project.

“If we’re trying to make something that’s beautiful, we have to recognize the things we see that are beautiful,” Toews said.

This extends to the human side of a commission. Hiring an architect “makes [clients] completely stressed out,” Davies said. “It’s all their money. It’s all their worries and anxieties and hopes and dreams. It’s not like buying a handbag, where you touch it and it’s yours. At best you have a rendering. It’s a huge, gigantic, leap of faith.”

And then there are the people whose work on the project—the individuals whose livelihoods depend on architecture, and whose experience of the world may overlap only for this effort. Plumbers, engineers, contractors, bricklayers: “[They] have their personal lives, and they miss days because of divorce and children and sickness,” Davies said. “It’s this huge human undertaking to get a wall right.”

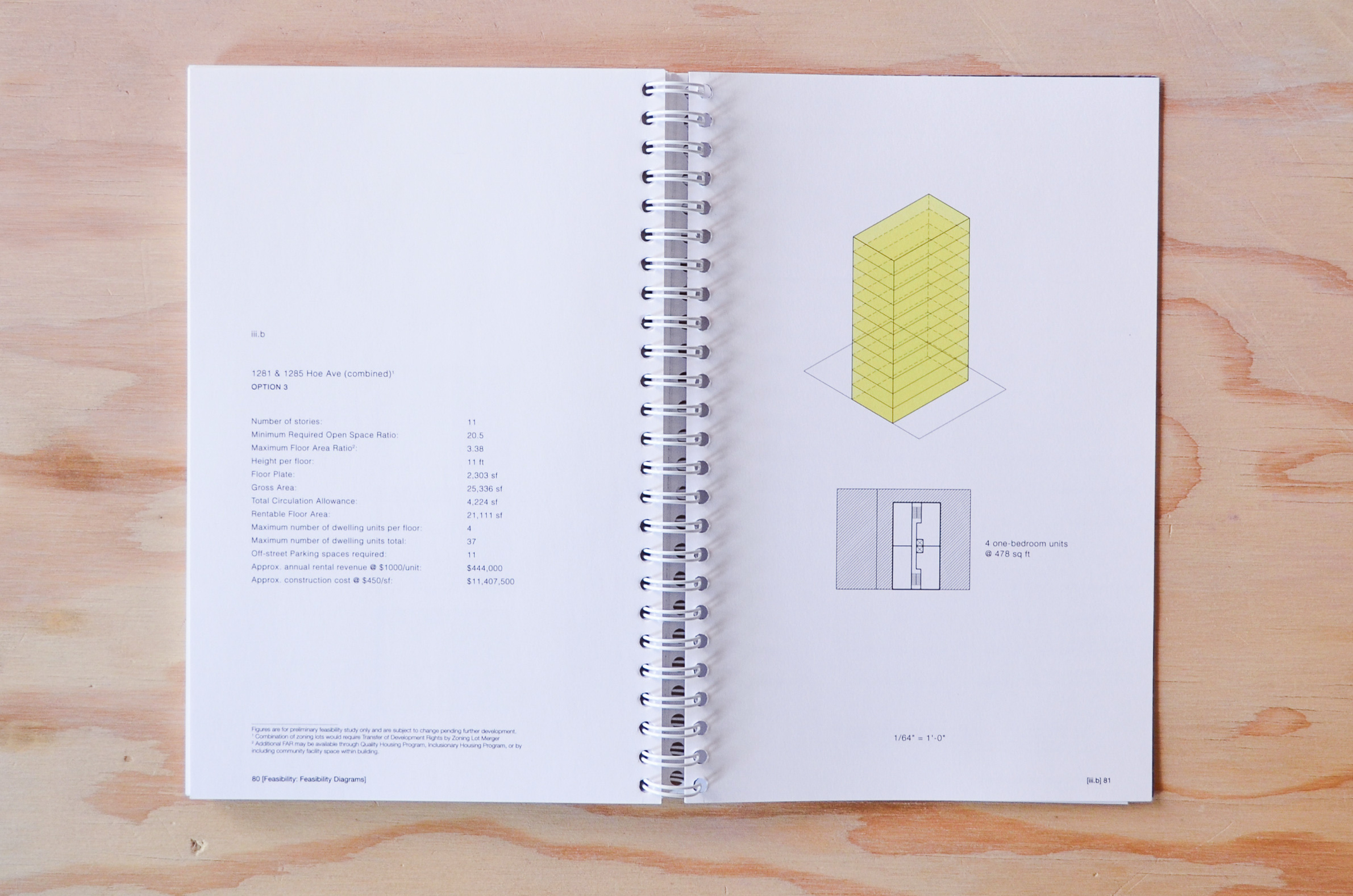

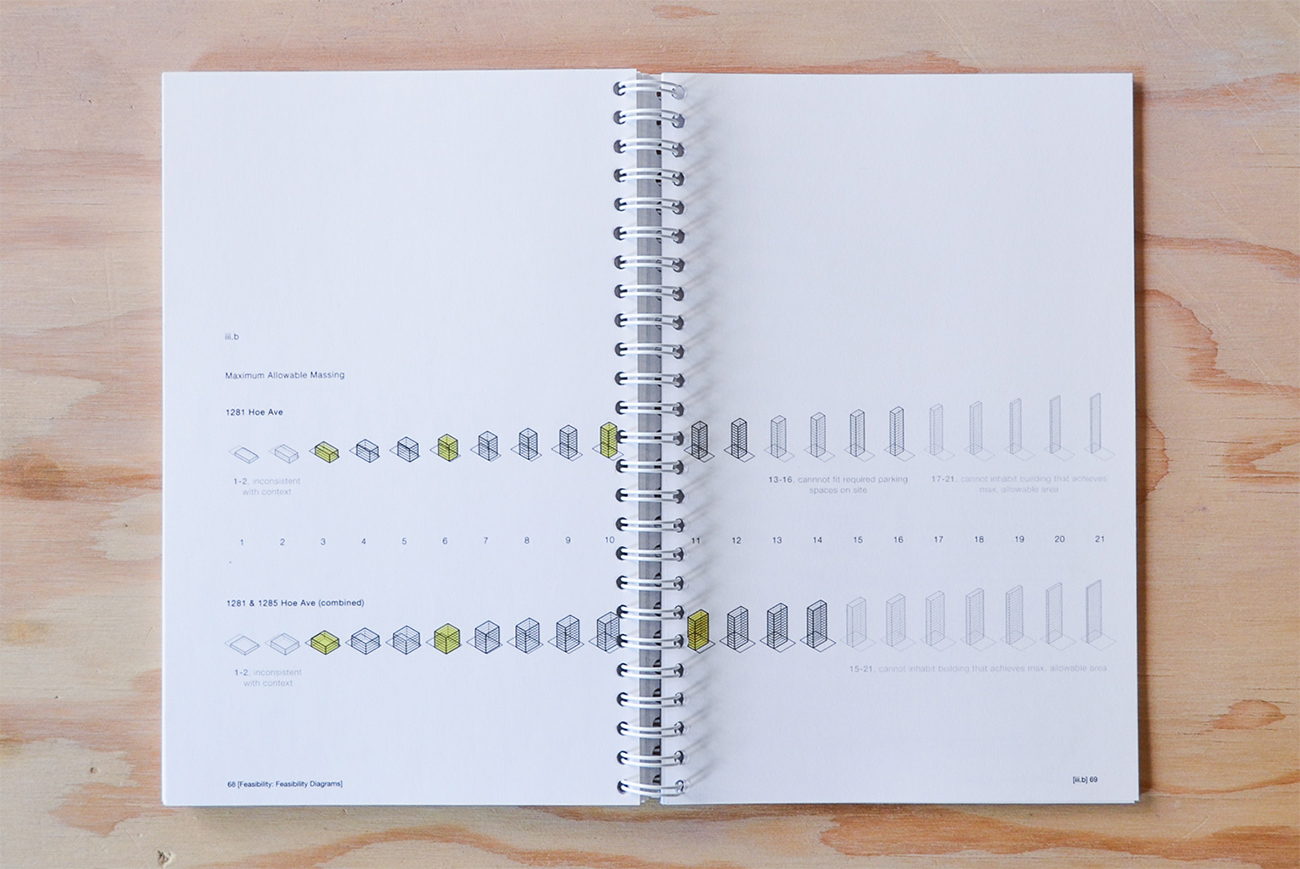

Some of the firm’s books are projects in and of themselves. In 2018, an engineer told Davies and Toews about a dilemma facing his doorman. The doorman owned property in the Bronx and, with real estate speculation on the rise, was being approached by developers. But with little understanding of the property market, he wasn’t sure who to trust. Davies and Toews researched the site and pulled together the information he needed to feel confident speaking with would-be buyers.

“We made him a book,” Davies said, “so that when people come to his property to ask him sell it to them for $5 or whatever they’re trying to do, he’s like ‘Well, as a matter of fact, if you’re interested in investing with me, my FAR is . . . ’”

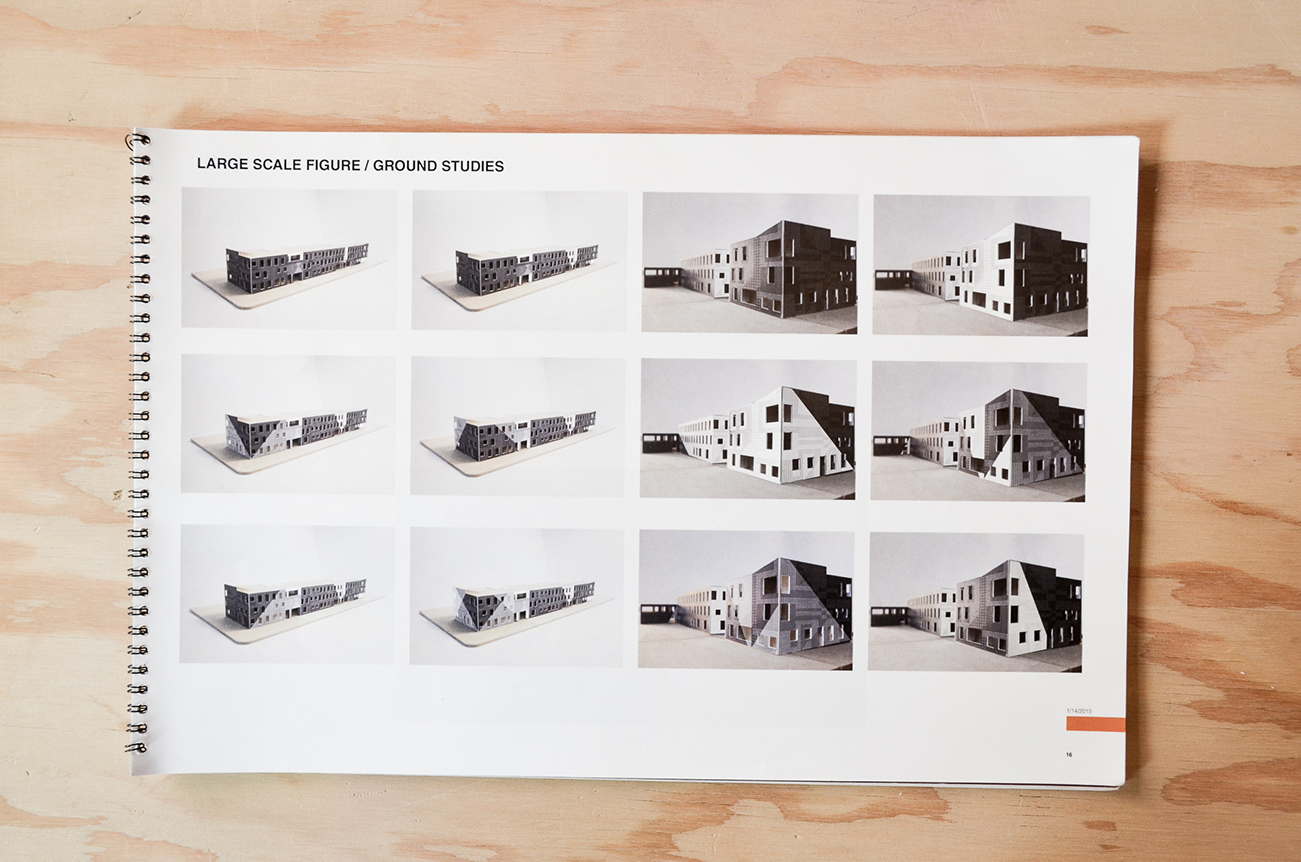

Other volumes are used to communicate with project stakeholders. While working on a Chicago school with a large, multifaceted client group and a tight timeline, Davies and Toews made an in-depth presentation book each week to help guide the conversation during Wednesday meetings.

“We got it down to, fly back on Thursday. Download on Friday. Saturday, Sunday we make the models. Monday we photograph. Tuesday we print. The next day we get on the plane,” Davies said.

The books also serve as a kind of bittersweet reminder of the creation of spaces the designers know intimately but may never see again once the occupants move in.

“For us,” Toews said, “this is the life of a project.”

Explore

The architecture of the everyday

For Stephanie Davidson and Georg Rafailidis, mundane issues like the weather and mortgages serve as a springboard for design investigation.

Leong Leong lecture

The designers describe work ranging from an experimental boutique in New York to an LGBT campus in Los Angeles.

The simplest move for the biggest impact

An interview with SPORTS, winners of the 2017 League Prize.