A 2016 report by the Youngstown/Warren Chamber of Commerce shows that five out of the top ten labor sectors in the area are in health. As industrial jobs leave the area, that number is only increasing. Hospitals are expanding and new schools of nursing are opening.1Youngstown/Warren Regional Chamber, Youngstown/Warren Metropolitan Profile, 2016, p. 7.

An hour’s drive to the north, the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospital systems have demonstrated how healthcare providers can become reliable anchor institutions for economic and urban development. For example, the employee-owned Evergreen Cooperatives, a successful grassroots economic development initiative, relies on this “anchor” institution model for its financial stability.

In 2015, Ted Howard, the president and co-founder of the Democracy Collaborative, a group that played a key role in setting up these Cleveland-based cooperatives, said this about the role of health anchor institutions:

By adopting an anchor mission, healthcare institutions and systems can produce measurably beneficial impacts on individual and community health, and by so doing, lower preventable demand on the healthcare system. The result is a win-win: refocused hospital business practices and operations produce conditions in which citizens and communities become healthier. This prevents avoidable demand on the health system, which in turns lowers costs and makes care more affordable for those truly in need. Healthcare professionals call this “moving from volume to value,” a process in which hospitals are rewarded for improving health, rather than delivering more care.2Howard, Ted. “Can Hospitals Heal America’s Communities?” The Democracy Collaborative. See source.

The Democracy Collaborative is now seeking to bring this vision to other communities with its Healthcare Anchor Network. The network counts Mercy Hospital, the largest healthcare institution in the Youngstown–Warren region, as a member.

This health anchor network approach is a hopeful, but as of yet not fully proven, strategy, and one the Mahoning Valley hopes to successfully embrace. The region has experienced significant closures and consolidations of healthcare facilities in recent years. In Warren stands the abandoned St. Joseph Riverside Hospital, closed in 1996 after population loss led to the merging of healthcare institutions. The large building is now a vandalized, dilapidated eyesore. After years of dereliction, the community is still actively looking for funds to demolish the building and reuse the land.

Just down the Mahoning River, the Northside Regional Medical Center in Youngstown was closed by the for-profit Steward Health Care system in 2017 due to not meeting profit expectations. Although there are plans to lease out space within the now-vacant building, the neighborhood has noticed the hospital’s absence, as hundreds of doctors and nurses have left to find work in other areas.

We begin our look at health in the region with a series of maps, graphics, and quotes from local stakeholders, introducing the growth, consolidation, and accessibility of healthcare institutions in the Mahoning Valley. They are followed by an essay that looks in more detail at the Democracy Collaborative’s Healthcare Anchor Network initiative and its hopeful economic model. —Quilian Riano, In the Mahoning Valley chief editor and Kristen Zeiber, In the Mahoning Valley mapping/graphics editor

Part I: Mapping Health

GROWTH AMID CONTRACTION

Download a PDF of this graphic.

In the years between 2002 and 2017, total employment in the Mahoning Valley fell by 12.8 percent, while local healthcare employment grew by 8.3 percent.

After 89 years serving the city of Youngstown, the Northside Medical Center hospital closed in 2018, causing a loss of 468 jobs. There is discussion of reusing the facility for veterans’ services, but a new VA hospital under construction in the city renders this possibility unlikely.

The closure of Northside Medical Center was countered with the growth of many smaller medical providers in Youngstown’s southern and eastern suburbs, for an overall growth in the healthcare industry in the Valley.

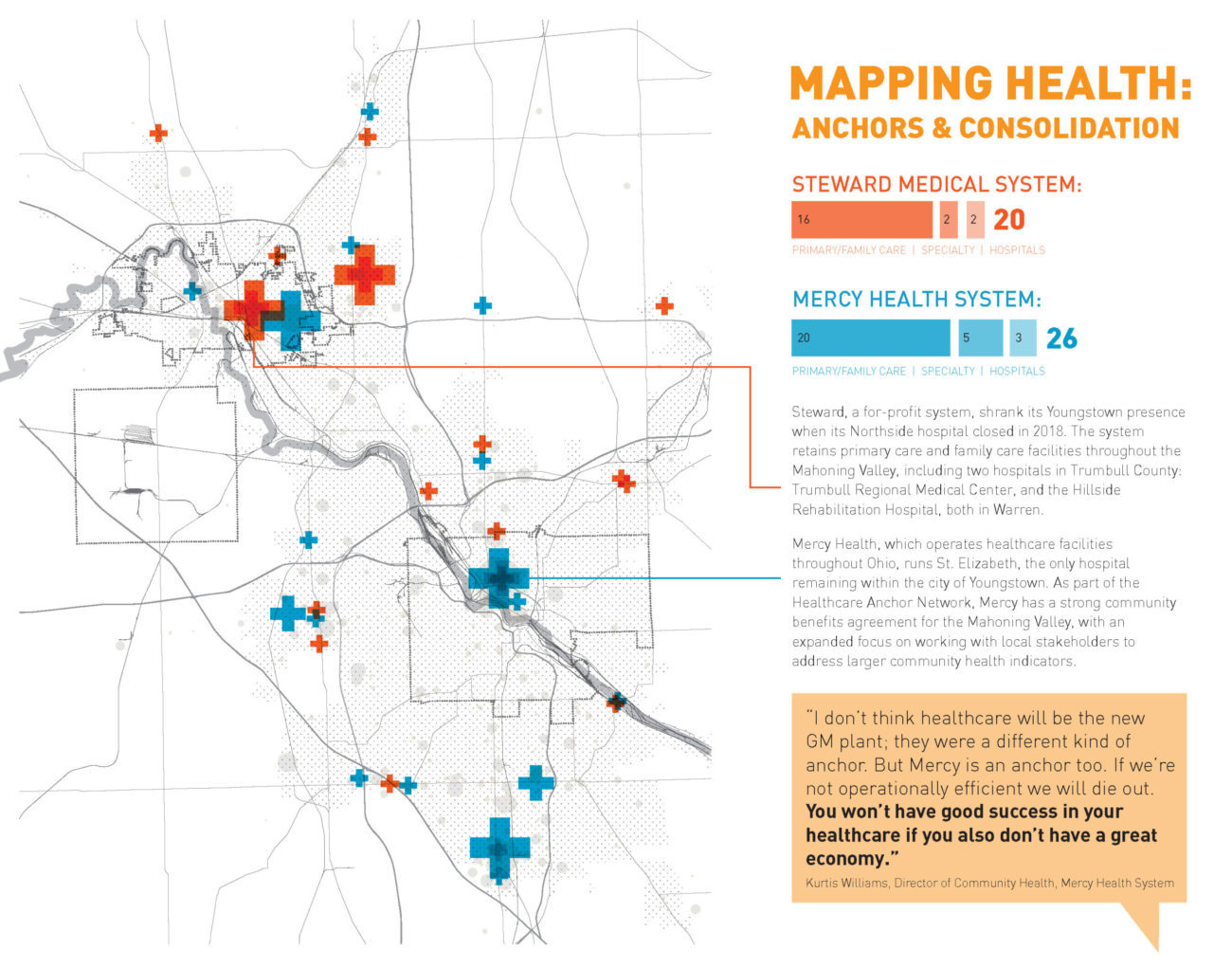

ANCHORS & CONSOLIDATION

Download a PDF of this graphic.

Steward, a for-profit system, shrank its Youngstown presence when its Northside hospital closed in 2018. The system retains primary care and family care facilities throughout the Mahoning Valley, including two hospitals in Trumbull County: Trumbull Regional Medical Center and the Hillside Rehabilitation Hospital, both in Warren.

Mercy Health, which operates healthcare facilities throughout Ohio, runs St. Elizabeth, the only hospital remaining within the city of Youngstown. As part of the Healthcare Anchor Network, Mercy has a strong community benefits agreement for the Mahoning Valley, with an expanded focus on working with local stakeholders to address larger community health indicators.

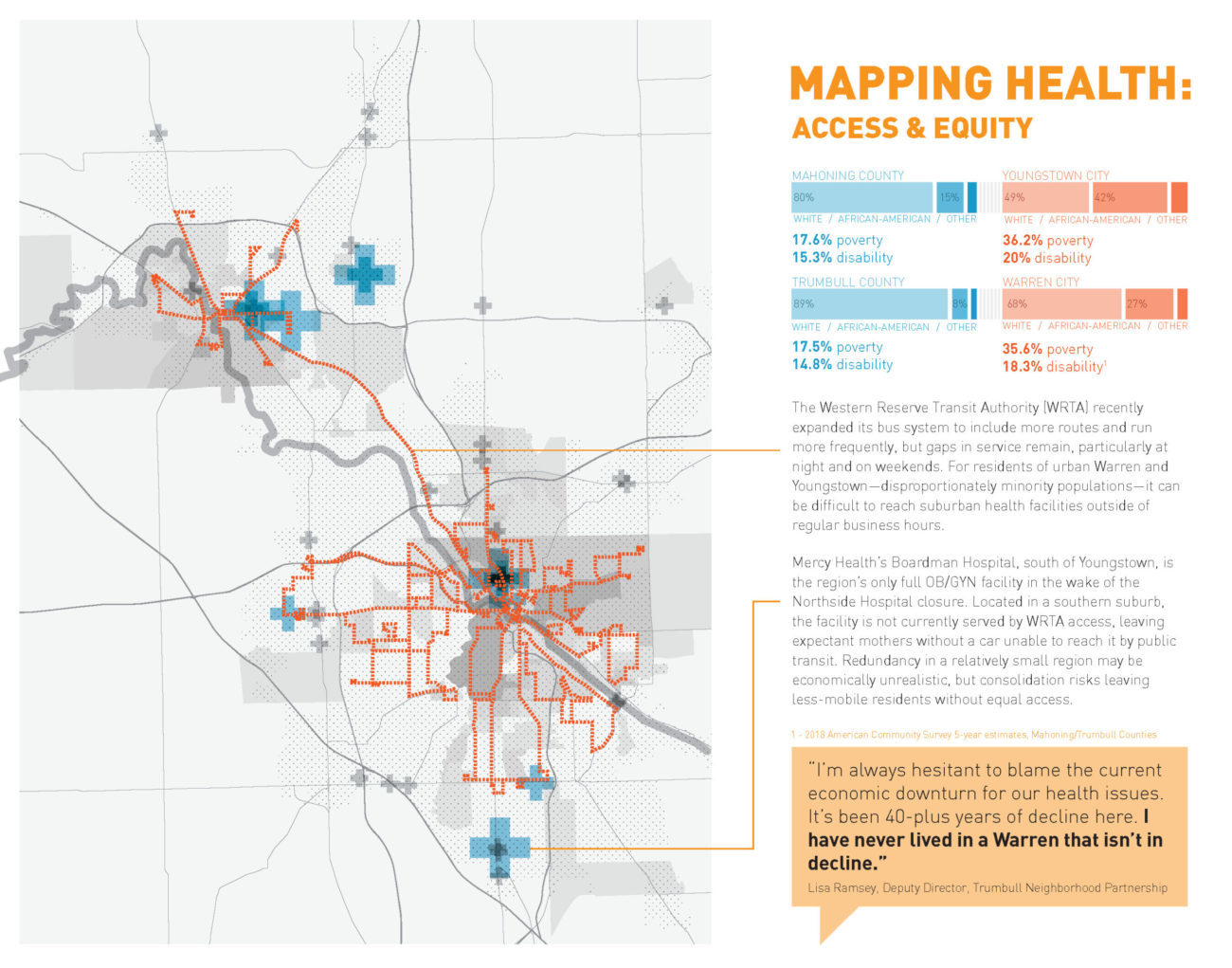

ACCESS & EQUITY

Download a PDF of this graphic.

Residents of Youngstown and Warren are more likely to be both poor and non-white than their neighbors in surrounding Mahoning and Trumbull Counties.

The Western Reserve Transit Authority (WRTA) recently expanded its bus system to include more routes and run more frequently, but gaps in service remain, particularly at night and on weekends. For residents of urban Warren and Youngstown—disproportionately minority populations—it can be difficult to reach suburban health facilities outside of regular business hours.

Mercy Health’s Boardman Hospital, south of Youngstown, is the region’s only full OB/GYN facility in the wake of the Northside Hospital closure. Located in a southern suburb, the facility is not currently served by WRTA access, leaving expectant mothers without a car unable to reach it by public transit. Redundancy in a relatively small region may be economically unrealistic, but consolidation risks leaving less-mobile residents without equal access.

Part II: On the Role of Health Anchors in Helping Build Community

In 2008 the Cleveland Foundation, the City of Cleveland government, the Ohio Employee Ownership Center at Kent State University, and The Democracy Collaborative at the University of Maryland, College Park, helped form the Evergreen Cooperative Initiative.

This initiative was developed alongside some of the most important health anchor institutions in the area, the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals. Modeled after the worker-owned cooperatives under the Mondragon Corporation in the Basque region of Spain, the Evergreen Cooperative Initiative was designed to take advantage of the economic prowess of the local health anchors to create ownership and training opportunities for local low-skill and low-income workers. The Cooperative’s workers now collectively own a solar energy company, a laundry, and an urban farming operation, all built primarily to serve the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals. In short, this project seeks to reshape economic relationships, with the specific goal of making local big institutions players in the evolution of their neighborhoods and cities.

Since this first cooperative (and experiment with anchor institution responsibility) in Cleveland, the Democracy Collaborative has kept moving the concept of the anchor institution forward, and in 2016 created the Healthcare Anchor Network. The hospital Mercy Health Youngstown has now joined the network, along with over 50 other members.

The network serves as a place for hospitals and health systems to better understand their role in their communities and to adopt what the Democracy Collaborative terms the Anchor Mission, defined as “A commitment to consciously apply the long-term, place-based economic power of the institution, in combination with its human and intellectual resources, to better the long-term welfare of the communities in which the institution is anchored.”

The goal is for health institutions to take a holistic approach to working within a community, considering place-based issues integral to the health of the community, and thus the institution. This strategy includes economic indicators, but also quality of life and built-environment issues.

Mercy Youngstown is just one of the health anchors located across Northeast Ohio. Photograph courtesy of the In the Mahoning Valley editors

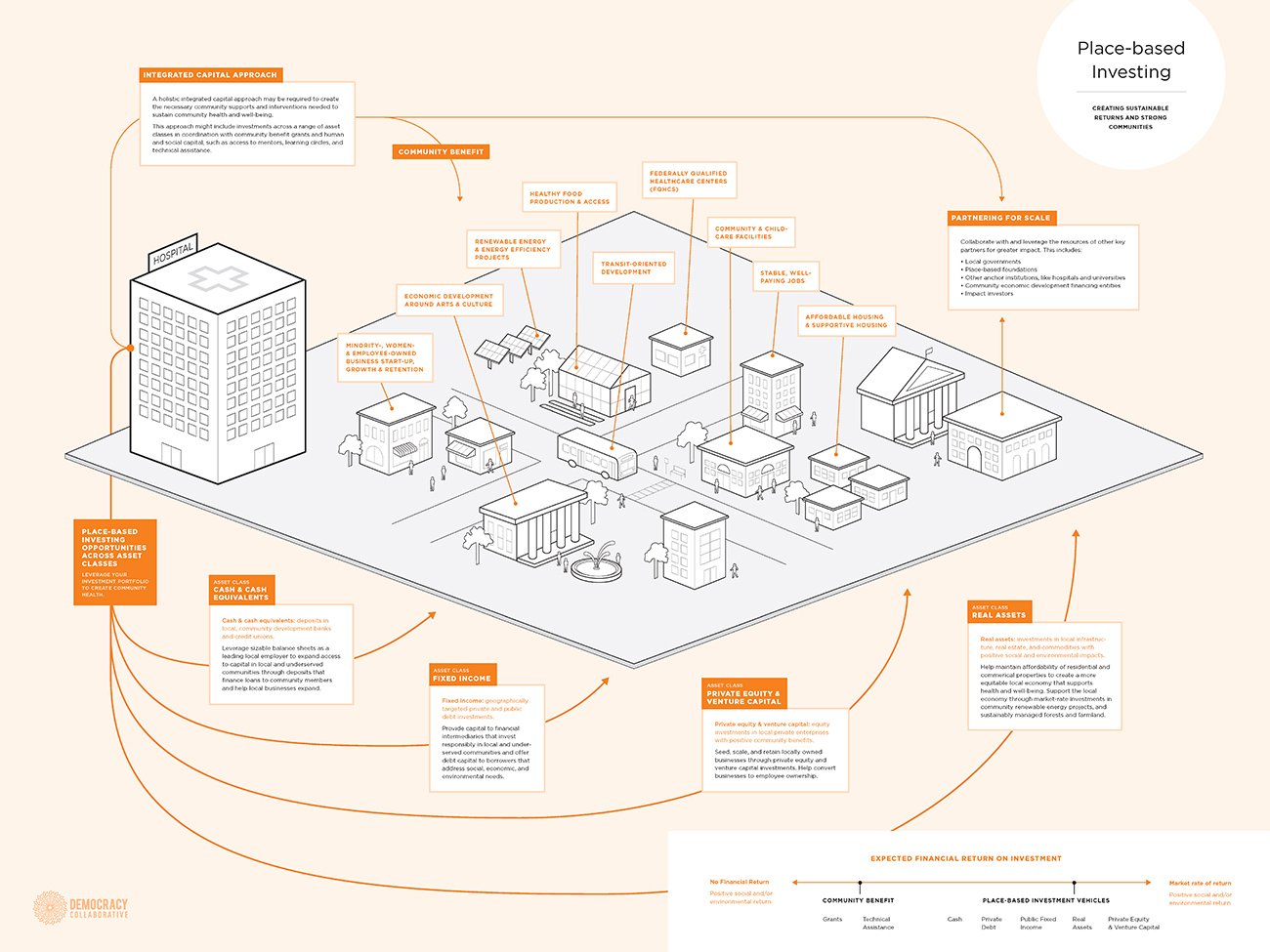

In the diagram below, it is clear that the Democracy Collaborative’s vision for what anchor institution–leveraged funding can create includes new housing, public building investment, and infrastructural and urban design improvements. This offers a role for architects, landscape architects, urban designers, and others to play as part of a comprehensive approach to community wellbeing.

Infographic by the Democracy Collaborative on how a healthcare anchor network and place-based investing can influence communities and their spaces. Credit: Democracy Collaborative, Place-Based Investing

Download a PDF of this infographic.

While there is no definitive proof yet that the Healthcare Anchor Network and its affiliates will be able to fulfill its vision, there is hope in Youngstown for this model.

Biographies

is an associate director of Kent State University’s Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative (CUDC), where he provides strategy and design coordination for the CUDC’s urban design, applied research, engagement, publication, and academic activities. Riano is also the founder and lead designer of DSGN AGNC, a design studio exploring new forms of political engagement and co-creation through architecture, urbanism, landscapes, and art. He teaches graduate architecture and urban design studios at Kent State University and has also taught design studios at Harvard University, Carleton University, Columbia University, Parsons The New School of Design, The Pratt Institute, Syracuse University, Wentworth Institute of Technology, and the City College of New York. Riano holds a bachelor’s degree in design from the University of Florida and a master’s in architecture from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD).

has been a project manager with the CUDC since 2013. She contributes to the full range of the CUDC’s practice, including neighborhood planning and mapping, community engagement, design research, and graduate-level instruction. She is a licensed architect and holds a master’s degree in architecture and urbanism from MIT and a bachelor’s in architecture from Penn State University.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.