Mahoning Valley, Ohio

Field Notes: The Mahoning River as Urban Reinvention

In 1796, John Young arrived on the banks of the Mahoning River to survey the land he planned to purchase from the Connecticut Western Reserve.1Learn more about the Connecticut Western Reserve. It was the river that convinced Young to buy the land and create a settlement on its banks: the future Youngstown. For almost two centuries, the Mahoning functioned as the backbone of its communities, providing transportation, recreation, food, and eventually industrial resources.

River access was one of the main reasons why so much industry developed in the Mahoning Valley. The river was used as coolant, and as a transport corridor. Eventually, its waters became polluted and overheated, in parts completely devoid of life and in places too scalding for human activity. This environmental degradation led the Mahoning Valley to turn away from the river. Not only was it despoiled, it became fully associated in people’s minds with the area’s industry and its ills.

In a way, the exploitation and subsequent degeneration of the river and its natural systems mirror the effects of industry on its surrounding communities. The Mahoning River remains a central feature that defines the local landscape, but its industrial past relegates it to an often forgotten and ignored natural resource. What are the possible futures for a river whose identity has been so closely tied to industrial loss and pollution?

Today, after much of the region’s industry has receded, many brownfield sites remain along the river. The Copperweld Steel site on the north side of Warren, for example, now lies vacant: remaining structures sit empty and slowly rusting; fields closer to the river are unused. It’s a legal and bureaucratic headache in physical form. On the southern border of Warren, the former BDM steel factory site has gone through initial remediation but currently lacks meaningful new use. These massive sites could represent new development opportunities for the region if their industrial legacies can be reenvisioned.

There are signs that the Mahoning’s identity as the region’s physical and spiritual backbone may be returning, principally due to a massive undamming effort. The Eastgate Regional Council of Governments, located in Youngstown, is organizing an effort to remove a series of nine small dams that were originally constructed to divert water for now-defunct industry. The plan includes remediating the natural systems of the river to attract recreational uses, leveraging this engineering process as a larger economic development tool. The council has also contracted a planning consultant to help reimagine the future of the river and its adjacent communities, all with the aim of repositioning the Mahoning as the region’s spine.

This re-embrace of the river is already occurring in the village of Lowellville, southeast of Youngstown. The site of the first dam removal, the village is using the opportunity to reorient itself back to the river, create new riparian community, retail, and residential spaces. The village also hopes to connect to larger, region-wide recreation networks as a way to bring further economic activity.

The following field notes explore this dam removal initiative. This essay was developed, in part, from a June 2020 visit to Lowellville, Ohio, the site of the first dam removal, by the editorial team and local stakeholders. —Quilian Riano, In the Mahoning Valley chief editor

Explore the forces that have shaped the Mahoning river and, in turn, the region, in a photographic essay by landscape architect Charles Frederick.

With large deposits of iron and coal, the Mahoning Valley has been long known as a site for industrial production, first of iron, then steel, and then car manufacturing. One of the keys to the industrial success of the area is its reliance on the Mahoning River for both transportation and as a natural resource for manufacturing processes.

The Mahoning River begins in Northeast Ohio, flows south towards the Ohio River, and eventually merges with the Mississippi River on its way to the Gulf of Mexico. This set of local, regional, and national connections has made the river instrumental in the forming of the Mahoning Valley and communities along its banks, such as Warren, Youngstown, and Lowellville. It has also been a key part of industrialization in the area. Beginning in the early nineteenth century, the river was used to cool machinery for the iron and steel industry. This mostly happened through the building of low-head dams—small structures of low height that span the width of a river to pool water upstream for various uses—by factory owners. The industries would dam the river, divert the water to cool down their furnaces and other equipment, then dump scalding water, at temperatures well above 100 degrees Fahrenheit and filled with industrial materials and chemicals, back into the river, killing off flora and fauna in the waterways and riverbanks and preventing any other uses by local communities.2Friends of the Mahoning River, “About the River,” accessed April 2, 2021

Republic Steel plant along the Mahoning River in Youngstown, Ohio. Courtesy of Youngstown, Ohio, Steel Valley Artifacts

The Mahoning River was once a center of recreation and transportation, but after the industrial boom starting in the late nineteenth century, cities began to turn their backs on the river and its pollution. Today, the Mahoning Valley is characterized by the homonymous river at its center, yet when you stand just steps from its shores in downtown Warren or Youngstown it is easy to miss altogether.

Industry began to close down and leave the Mahoning Valley in the 1960s, devastating the local economy and leading to a loss of tens of thousands of residents. The subsequent examination of closed factories and mills also made clear the environmental damage done to the Mahoning River over the previous century. In the 1970s, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released studies showing that the river contained heavy metals, oils, ammonia, cyanide, and other toxins and pollutants at levels that exceeded water quality standards. It was neither a safe nor clean waterway.3United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Mahoning River Waste Load Allocation Study,” by Gary Amendola, Donald Schregardus, Willie Harris, and Mark Moloney, accessed April 2, 2021.

Yet the loss of industry and population meant that less pollution was being released into the river. As environmental conditions were improving, the US Army Corp of Engineers (USACE) released a study in 2013 identifying the low-head dams that industry had built along the river as a major reason why toxic sediment was not moving through the river’s natural flows and systems. The USACE identified removing low-head dams, alongside treatment and removal of toxic sediment, as key to the continued ecological restoration of the Mahoning River.4GPD Group and Enviroscience, “Mahoning River Corridor Evaluation Study,” accessed April 2, 2021.

Beginning in 2019, the Eastgate Regional Council of Governments, an association for local governments in Northeast Ohio (Ashtabula, Mahoning, and Trumbull Counties), created the Mahoning River Restoration project to remove nine low-head dams along the Mahoning River. Eastgate’s goals, according to executive director Jim Kinnick, is to remove nine dams in nine years for 90 million dollars. Kinnick says that at this time they are beginning to think that the project will actually take three to four years and may cost as little as $28 million as the group works closely with the EPA and testing grows more sophisticated, thus lessening the costs of removing and hauling sediment.5Learn more about the Mahoning River Restoration and Dam project.

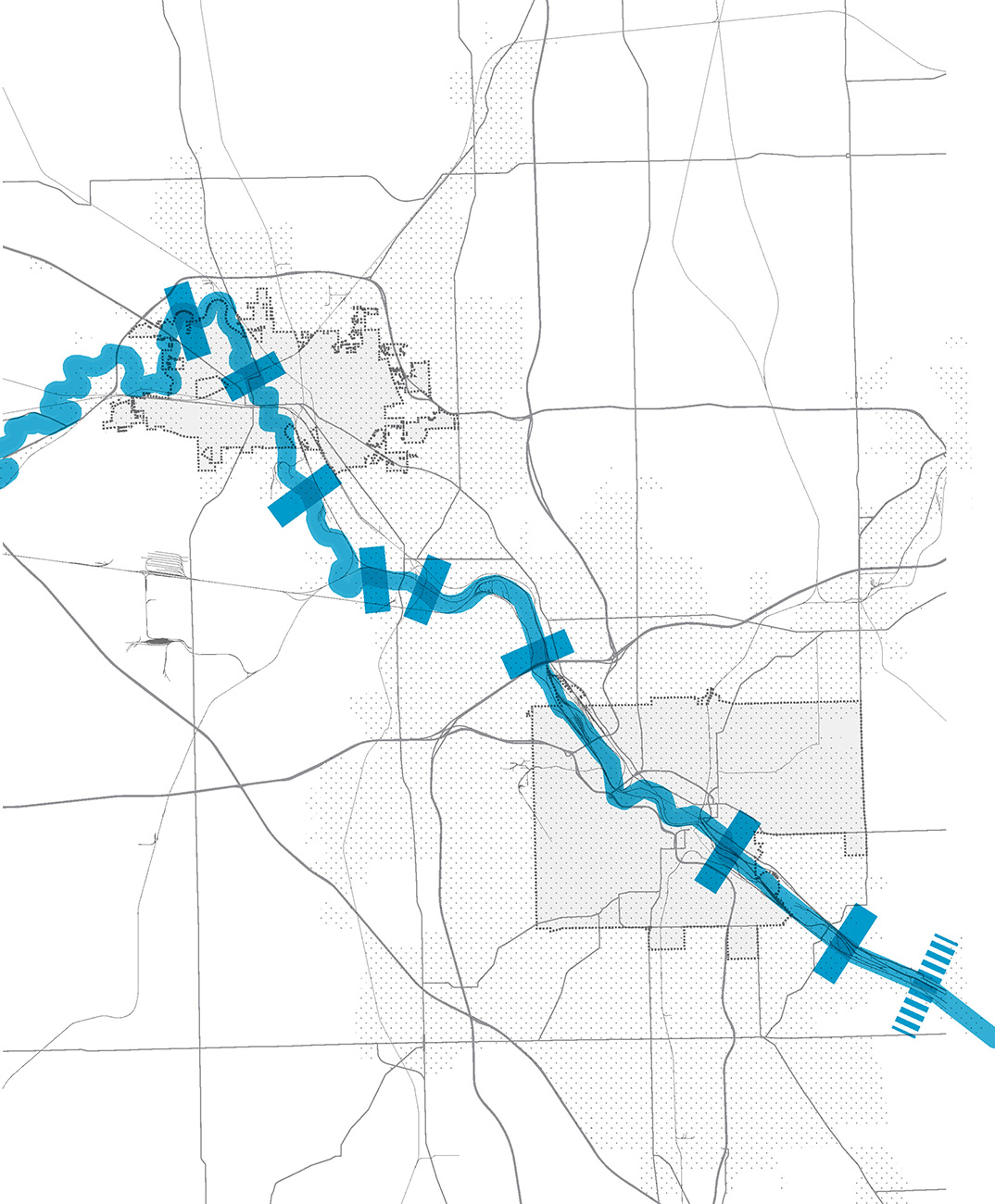

Location of dams along the Mahoning River (Warren to the north, Youngstown to the south; Lowellville indicated by the dashed mark in the far southeast). Credit: In the Mahoning Valley editorial team

The dams Eastgate is targeting are located in the cities, townships, and villages of Warren (two dams), Niles, McDonald, Girard, Campbell, Youngstown, Struthers, and Lowellville. The goal of the project is to clean up the river but also to turn it into an environmental, recreational, and economic engine for the Mahoning Valley community. Eastgate and the communities along the river see opportunities to have the cities in the area face the river, dotting it with new buildings and areas with housing and recreation. Jim Kinnick says that the Mahoning River “dams were built to trap water to cool the steel that built the country—now we need some help to remove them and clean our river.” Eastgate’s director of planning, Joann Esenwein, emphasizes that “the dams were built for the mills. They are not there for the benefit of the river.”

The first of the dams removed in late 2020 is in Lowellville, a village with a population of roughly 1,000 inhabitants on the edge of Mahoning County. The village rose on the northern shore of the river around the large Sharon Steel Works’ Mary Furnace site, one of the first in the world to use raw coal as fuel. The Mary Furnace site was located just south of Lowellville’s downtown, across the river and along railroad tracks. In its heyday, the plant employed over 1,000 people; it closed in 1960.6Agis Salpukas, “2 Steel Shutdowns in 17 Years Hurt Town,” New York Times, October 22, 1977. Lowellville currently faces dual challenges as it tries to both retain its young people—the median age in Lowellville is 45.1 years, about seven years older than the national median age of 38 years—and attract the industry and retail needed to provide those young people and the village with amenities and economic stability.

Lowellville Village mayor James Iudiciani in front of Lowellville’s comprehensive plan and other economic development project boards. Credit: In the Mahoning Valley editorial team

Lowellville’s mayor, James Iudiciani, sees the dam removal as a major opportunity for the village. Born in Lowellville around the same time as the Sharon Steel Works plant closed, Mayor Iudiciani remembers the stern warnings against going into the river as a child. He says that he “know[s] that the jobs that were lost from the steel companies are not coming back. It is about creating new opportunities for our young people.” That is just what he has set out to do by hiring Columbus, Ohio-based architect Jeff Glavan to make a comprehensive plan that identifies sites on the banks of the river and the former Sharon Steel Works site as potential sites for economic growth: the river to be used for recreation and tourism, and the Sharon Steel site to attract industrial and logistics jobs.

Standing in the Stavich bike trail looking towards the Mahoning River through rail yards and Lowellville’s commercial corridor. Credit: In the Mahoning Valley editorial team

In Lowellville’s vision, new landscape and architecture projects complement the river restoration project. Together, these efforts will lead to a town actually turning towards its waterfront. Furthermore, the plans to reconfigure the city’s riverfront revolve around Lowellville’s geographic location and potential for recreational uses. Lowellville is located about 70 miles away from Cleveland and Pittsburgh and has the potential to attract adventure-seekers from across the region. For example, the Stavich bike trail, which connects New Castle, Pennsylvania, to Struther, Ohio, passes through the heart of Lowellville. The bike trail currently sees a ridership of around 8,000 bikers per season. Poised to take advantage of what that could mean, Lowellville engineering consultant Christopher M. Kogelnik says that he envisions a future in which “we will have paddling in the river and pedaling on its banks, attracting more people into the village and its businesses.”

The plans for the Lowellville riverfront include building a boat launch as well as a community center with civic and retail spaces. A new local venture called Mahoning Whitewater Adventure has been created to both offer tours of the area as well as rent kayaks and bicycles to visitors. Mayor Iudiciani and his government have also slowly bought undeveloped land on the riverfront, which is a federally designated Opportunity Zone—a federal program that incentivizes development through preferential tax treatment in economically distressed communities—that they hope to see turned into local businesses, coffeeshops, restaurants, and hotels.

The idea of using the riverfront as an economic and civic engine is not new to Lowellville. Both Mayor Iudiciani and Chris Kogelnik point to an 1987 mural drawing by then-teenager Jan Hudak that envisioned a village that would celebrate the Mahoning River by creating safe ways to interact with the river through kayaking and canoeing as well as with civic and public architecture leading to the river. This vision struck a chord with the community, but it has taken over 30 years of coalition-building and fundraising to turn its ideas into a reality. During that time, some of the buildings and other infrastructure depicted in the mural have been lost, a fact that Mayor Iudiciani laments, making it all the more urgent to implement the village’s comprehensive plan before more is lost.

Mural painting of a restored Mahoning River waterfront in Lowellville by Jan Hudak, 1987. Credit: In the Mahoning Valley editorial team

Back in the river, the work of removing the dam is well on its way, led by the Marucci and Gaffney Company, a construction and engineering firm. Its work is being seen as a pilot for how the rest of the dams on the Mahoning will be removed. James Murray from Maruddi and Gaffney shares that after some initial setting up and dredging of the river, they plan to build a bridge-like structure with a jackhammer on it that will remove the dam little by little while minimally touching the river itself. As they remove the dam, they are setting up docks and creating sites for future buildings and parks that will bring Lowellville’s residents and visitors closer to the river.

Nearby communities with dams along the Mahoning River are looking at Lowellville’s process to see what may be possible for their urban waterfronts. About four miles away from Lowellville, the dam removal project in Struthers is next. The hope is that lessons learned about environmental and urban renovation in Lowellville will translate to that project and beyond. Through restoring and cleaning the river, the entire region once again looks toward the Mahoning as part of its civic, urban, and economic future.

Biographies

is an associate director of Kent State University’s Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative (CUDC), where he provides strategy and design coordination for the CUDC’s urban design, applied research, engagement, publication, and academic activities. Riano is also the founder and lead designer of DSGN AGNC, a design studio exploring new forms of political engagement and co-creation through architecture, urbanism, landscapes, and art. He teaches graduate architecture and urban design studios at Kent State University and has also taught design studios at Harvard University, Carleton University, Columbia University, Parsons The New School of Design, The Pratt Institute, Syracuse University, Wentworth Institute of Technology, and the City College of New York. Riano holds a bachelor’s degree in design from the University of Florida and a master’s in architecture from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD).

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.