On the occasion of their 2013 and 2014 Current Work lectures, structural engineer Guy Nordenson and architect Thomas Phifer sat down to discuss their 25 years of collaboration, their conceptual approach to projects, and their joint work on the North Wing addition to the Corning Museum of Glass.

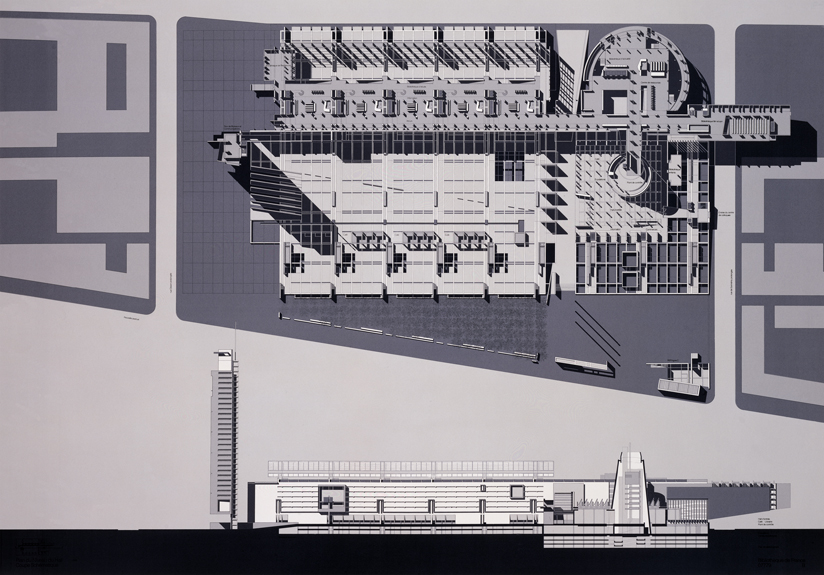

Guy Nordenson: I think that the first time you and I worked together was on Richard Meier’s entry for the 1989 competition for The National Library in Paris. You worked in Meier’s office then, and I was thrown in as a meager substitute after Peter Rice respectfully declined. So I walked in feeling like they were inevitably going to be incredibly disappointed, but you had a very warm, welcoming presence. We had a lot of fun working on that competition.

Thomas Phifer: That was one of Richard’s grand projects. He didn’t make many. He had some corporate headquarters, he had some smaller projects, but this was one of the big, big competitions he entered, and it was really fun to do. It wasn’t often in that office that we were able to really think about structure and architecture together, because most of the structural work was covered up, but with that particular project there was an opportunity to be more expressive and authentic about the structure of the building. I think that was a really nice collaboration.

Nordenson: One of the things I really liked about that project was that it was this long, very simple rectangular bar facing the river that cantilevered from the landside, floating like a tonearm. It was one of those very basic structural ideas, but developed really simply and nicely, just reaching out to the river.

Richard Meier & Partners | Competition entry for the French National Library, 1989. Credit: Richard Meier & Partners

Phifer: I think that project was very important to our later collaborations. It planted a seed. Two things in particular about the roof carried over: it was what kept the building cool (and warm in winter), and it also allowed for the daylight to come in and wash over the space in a very, very soft way.

Nordenson: Another project we did together that I remember fondly is the Rachofsky House, which I think is one of the most wonderfully resolved projects that you did at Meier’s office. It’s a beautiful house. It involved a big floating plane, set just out from the front of house. I still love that project, I think it’s a very clear, elegant design.

Phifer: A lot of the wonder of that project came from that floating wall—just a thin plate comes off and supports this entire wall. There was a little bit of magic there to make that happen. Had those connections been bigger or had the thing been conceived more heavy-handedly, the effect would have been lost. In a way, that moment really defined the house.

Phifer: The next time you and I worked together was very early on in my own practice, on the house in Spencertown, New York. Even though we were kind of feeling our way through the dark, I think we learned something about how to bring materials together in that project. The house had a back wall that was embedded into the earth, a columnar structure facing south, and this big roof that served as a sun-shade device during the summer. I’d like to hear you talk about how the back wall stabilized the house, and about the tiny, delicate columns in front. They didn’t look like they held up the louvers, much less the house.

Nordenson: You’re right that the simplicity of it was based on the fact that we could lean against the ground at the back to stabilize the house. We didn’t really need any major bracing, and that meant that the columns could just be little props, they didn’t have to do anything else for the structure.

Phifer: There was a huge amount of poetry in the roof beams and the repeating columns. I don’t think we quite understood it this way then, but I believe you and I were headed towards a kind of authentic, honest, stripped-down approach to building. Almost nothing was covered up; it was all there. Now advance ten years, and here we are working on the new Corning Museum building, which I think picks up very naturally from Spencertown: not covering anything up, letting pieces be exposed, letting light systems and structure come together. Spencertown was important from that perspective. It laid a groundwork.

Phifer: On Corning, we worked really closely with Andy Sedgwick at Arup to figure out what light we could use to give this glass an extraordinary spirit, to make it come alive. We learned that we needed light coming directly from above, but it must have taken us three months to figure out what the structure wanted to be.

Nordenson: Your approach was so fresh and radical—the simplicity and the calmness of the building on the outside, and then the energy of it when you get inside—I spent a lot of time just watching and getting excited as you developed that design. Part of the delight of the process for me was just thinking about how the roof would come together, and figuring out what those walls would be made of, because we went through a number of different ideas before we ended up where we are now.

Phifer: This is a collaboration based on a lot of shared experience, and a lot of shared values. You and I talk about the authenticity of a structure all the time. On Corning we really wanted everything to be completely together: the light, the structure, the systems, the whole theoretical approach to the building. It had to be engaging on all of those levels. But it started with this notion of bringing light in—if you look at all the things that you and I love, it always comes back to structure and light.

These beams that you have been working on, and the way they tie into the serpentine walls and keep the building sturdy, allowed us to start thinking about the perimeter wall as being light. It has an ethereal quality even though it’s a more solid building and not as “lacy,” say, as the Spencertown house. It has a lightness of being that I don’t think would have occurred to us had the structure not begun to tell that story.

Nordenson: Part of the discovery process for me involves seeing your other projects, like the Glenstone Museum, understanding the ways in which your interests and sensibility are changing, and then trying to find ways to contribute to that. For example, one of the big steps in the development of the Corning project was going from these serpentine block walls, that were more like partitions, to concrete walls that would also serve as the beams to hold up the floor below. That just seemed right given what you were working on and thinking about at the time. A big part of the excitement and energy of the project has been watching those concrete walls go up, figuring out how to form them in a simple way. But the fundamental idea for me was that it just felt absolutely right within the larger context of your work for those walls to be what they are.

And then you have these roof rafters, which, structurally, are the main event, and are difficult to pull off. They’re very thin, three and a half inches wide, four feet tall, and span fifty feet. The challenge was to get the minimum amount of horizontal bracing in there to keep them from toppling over, and also to find a fabricator in North America who was willing to make them! They are visually unexpected, these amazingly skinny structural elements. I think they are a big part of the magic.

Phifer: The building becomes very intriguing when you see these beams up there. At first you don’t understand that they are holding up the dead load of the skylight, stabilizing the serpentine walls, and keeping the building from toppling over. So we debated how to attach the beam to the wall, and what would be the proper expression to show how all these forces resolved. That piece turned out to be a very simple, but important moment in communicating how these different loads are coming together in the building.

Nordenson: You can spend time in there, following where elements are going; it’s all out in the open for somebody to read. There is simultaneously clarity in the structure and abstraction in the forms—the tectonics are clear, but they’re not overt, not fussy.

Phifer: It’s a very nice moment. The whole project has been an incredible collaboration. Neither of us could have predicted that we would have ended up here.

Nordenson: I agree. It has been truly collaborative, not just in the sense of inventing something new together, but in supporting somebody else’s sensibility and adapting your interests and your palette to that, out of respect.

Phifer: After a little bit of a hiatus from working together, it was almost like there was no break in the conversation. It’s amazing, you start to realize that it’s ongoing—even when we’re not actively working together, this shared sensibility continues to develop.

Nordenson: And that’s not always the case. Certainly there are those situations where you just plunge in and do what you can on a project. But I think we both feel a sense of responsibility to represent and embody a certain way of doing things that we want to sustain in the profession—to be an example of how people can work. In both of our careers we’ve seen times when professionals are more or less open to this kind of collaboration. It comes and goes, so it’s important to reflect on it when it goes well.

Biographies

Thomas Phifer, who founded his New York City-based firm Thomas Phifer and Partners in 1997, “approaches modernism,” in his own words, “from a humanistic standpoint, connecting the built environment to the natural world with a heightened sense of openness and community spirit that is based on a collaborative, interdisciplinary process.” The firm’s work includes the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh and the Brochstein Pavilion at Rice University in Houston, as well as a number of residential commissions in the Hudson River Valley. Thomas Phifer is a member of the League’s Board of Directors.

Recognized for his independent research and innovative, collaborative work with architects, Guy Nordenson, principal of the New York firm Guy Nordenson and Associates, is a structural engineer and professor of architecture and structural engineering at Princeton University. He began his career as a draftsman in the joint studio of R. Buckminster Fuller and Isamu Noguchi, and has practiced structural engineering since 1978. In 1987 Nordenson established the New York office of Ove Arup & Partners, serving as its director until 1997, when he began independent practice.

Explore

A walk through the University of Arkansas School of Architecture

A tour of the University of Arkansas architecture building with Marlon Blackwell and Tom Phifer.

The stereotomy of complex surfaces in French Baroque architecture

Hubert Pelletier describes the complex and beautiful structural surfaces of French Baroque architecture. 2009

Richard Meier

Richard Meier considers the duality of public and private space, evident in his dramatic drawings that articulate types of enclosure.