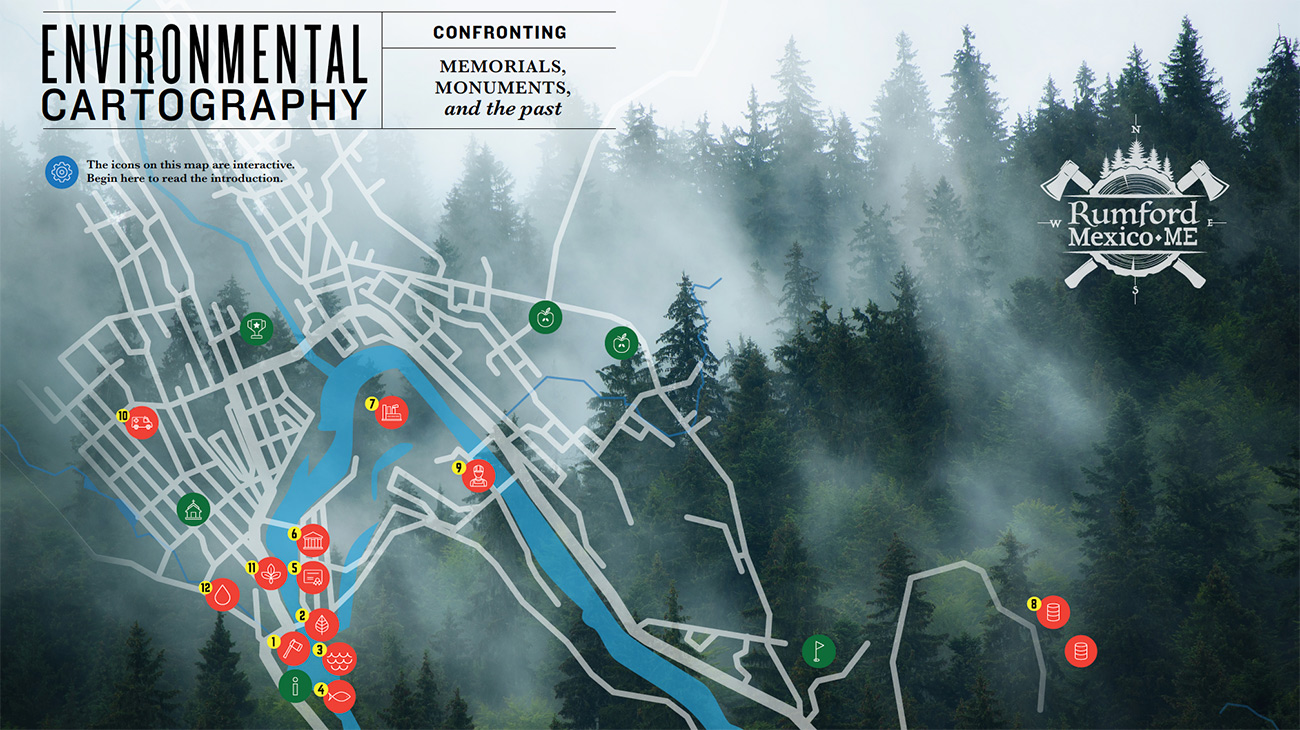

River Valley, Maine

Environmental Cartography: Confronting Memorials, Monuments, and the Past

In this two-part feature on the Environment, artist Nina Elder, graphic designer Elizabeth Kaney, and report editor Kerri Arsenault examine the consequences of resource extraction in the River Valley.

In part II, art director Elizabeth Kaney and author Kerri Arsenault reconsider Rumford’s tourist information booth in “Environmental Cartography: Confronting Memorials and Monuments.” The town’s information booth includes brochures that provide information about places to visit, where to eat, and what to do. The authors argue that this public-facing “information” overlooks the darker consequences of industrial development on the environment and the community. They remap the town to include toxic sites that are also part of the community’s legacy: forgotten ruins and people, sites of resource extraction, scars upon the landscape, invisible histories, and the path of toxics. —Maine’s River Valley report editors

Read part I of the Environment feature here.

The following text has been adapted from Arsenault’s book, Mill Town: Reckoning with What Remains. Please reference for additional discussion and sources on the region’s history and environmental challenges.

Rumford’s tourist information booth, on the waters of the Androscoggin River, offers brochures about the natural beauty of the River Valley. In them, you’ll find details on what tourists go there to do: ski, hike, snowmobile, fish, hunt, swim, or many other al fresco pursuits. If you look at the landscape, such activities make sense. The forest’s canopy is fractured by burbling brooks, a damp mossy understory, wildlife, and deep cold lakes. The mountains foster trails, adventure, steep hills, glassine lakes, and the solitude of nature so many people seek. Yet the River Valley’s memorials and monuments (sites) present conflicts between the promise of the sites highlighted in the brochures and the town’s industrial, colonial past.

For years, the area was ridiculed or avoided for its potent sulfurous smell, its dirty river, and the mill’s smokestacks perforating and polluting the skies. It was nicknamed “Cancer Valley” by a Boston TV station because of the high cancer rates. While there’s no scientific proof connecting cancers and the mill, there’s still a perception—and a very real possibility—that the two are linked. What will it take to remove this stigma, while recognizing the reality of the River Valley’s industrial past, so that the real beauty of the place is seen?

A giant statue of Paul Bunyan towers above the information booth, greeting tourists as they drive into Rumford. In blue pants, a matching blue watch cap, and a short-sleeve red polo shirt, Bunyan proffers an enormous ax in his brawny arms. As a kid, I never paid much attention to Bunyan, despite his size. He blended into the background, as impossible as that seems. Small towns from Maine to Minnesota claim Bunyan as their own, yet everyone agrees he was a hero to all woodsmen (like those who took Maine trees down). Legend says when Bunyan’s cradle rocked, the motion caused huge waves that sank ships, and he once whittled a pipe from a hickory tree.

Down at the Androscoggin River’s edge and just across the bridge from Bunyan, Edmund Muskie’s smaller, serious memorial of squat, dark gray granite sits solemnly aghast, much like a gravestone, but without a grave. Etched into two tablets that flank a bas-relief of Muskie with “Born in Rumford, Maine” underneath are dates and descriptions of his political rise. He served, according to the granite squares, in the US Navy and the Maine House of Representatives; as Maine governor, Maine senator, Democratic nominee for VP of the United Sates, and US Secretary of State. Under 1972 it says, “Authored the Federal Clean Water Act,” with no other contextualization to this momentous deed.

In 2002, the town repaired Bunyan’s structure and gave him a face-lift. In 2014, the community honored Bunyan with a festival in his name. It included a lumberjack breakfast, a facial hair contest, a lumberjack and lumberjill tug-of-war, and an axe-throwing competition, among other town-wide weekend-long events.

The tension between these tributes is clear. What Bunyan symbolizes is far from the fairy tale he inspires. He is a larger-than-life metaphor for resource extraction, which in the end he left for Muskie to—in a way—clean up.

What stories do the River Valley’s sites tell? Or more important, what stories do they forget?

The River Valley, like so many industrial communities, commemorates resource extraction, industrialization, and colonial projects, but avoids memorializing the environmental or social consequences of those processes, like the landscape, laborers, or First Nations people who may have been harmed in their wake. These sites also elevate one history and subdue others, without regard to the importance of those suppressed. What if instead of hosting a festival under Bunyan’s axe, we reconsider what that historical site means? With paper manufacturing on the decline, more considerate use of the River Valley’s landscape and concern for the health of its citizens could help the community survive.

We hope that the “What If?” scenarios in our new tourist map will force the public to confront the past in a persistent and unavoidable way. Residents, visitors, and leaders could no longer ignore or evade environmental and social legacies such as those the mill has left behind. Such a daily awareness would constantly reinforce the importance of mitigating and regulating toxics, and hopefully lead the community to act upon those concerns, which could in turn remove the stigma associated with the region. We hope, too, that this map inspires similar communities to rethink how they interact with their landscapes, and realize that they too can have some control over their futures.

Environmental Cartography Interactive Brochure

Step 1: Paul Bunyan

Step 1: Paul Bunyan

Rumford’s Bunyan model was crafted from the mold of the Muffler Man, a giant fiberglass statue who held mufflers in his outstretched hands as an advertisement on US byways in the 1970s. Other Muffler Men held hot dogs or fried chicken, and one in Illinois was found holding a rocket. The model was a blank slate for whatever fairy tale we chose. But Bunyan, he represented the lumbermen who harvested trees since the 1700s in Maine. Of the roughly 31,500 square miles that make up Maine, about 90% of it is forested, and thanks to Bunyan’s axe, no mature tree stands are left.

Maine’s forests have been used by our mill to make paper for over a century. And that industry has left another legacy beyond clear cuts and the rotten stumps of old trees. Until the 1990s, paper was bleached using elemental chlorine, which created one of the most dangerous family of toxics known to humankind: dioxins. Scientists found that workers most exposed to dioxins—even in the smallest amounts imaginable—were more likely to be at risk for cancer and ischemic heart disease. This included paper mill workers like my father, whose death was caused by both things. Government, industry, lobbyists, even the EPA won’t admit this, of course, because they say it’s hard to prove the link. But I see evidence in my father’s and grandfather’s graves. Dioxins can also impair sexual function, fertility, sperm count, childhood development. They can damage or suppress immune systems, interfere with hormones, harm unborn fetuses, and cause liver damage, infant cardiac malformations, neuro-developmental issues, and accelerated female development.

More than 90 percent of our exposure to dioxins comes through our food supply, in the fatty parts of living things like fish, clams, and cows as well as in byproducts like butter, eggs, parmesan cheese—things we eat in ample amounts. Because dioxins bioaccumulate, the further up the food chain they travel, the more concentrated and toxic they become. At the top of the food chain: the human body; at the very apex, human babies, whose breastfeeding mothers can expose nursing infants to dioxin levels 77 times higher than the EPA recommends.

WHAT IF… we covered Bunyan’s face with a mask of Senator Edmund Muskie, who tried to do more noble things with trees? Instead of that red shirt and blue pants, we could dress Bunyan in a suit like Muskie’s father (a tailor) would have made, one more befitting the senator’s job—a senator who tried to clean up the polluted rivers and the air of the entire United States?

Step 2: Edmund Muskie Memorial

Step 2: Edmund Muskie Memorial

Bookish and six feet four inches tall, Muskie was a giant in real life, although painfully shy (admittedly so) and smart: so smart that, as a student, he was asked more than once to substitute for his teachers when they fell ill. He pushed to overcome his shyness, a flaw he wore like a hair shirt, yet it vanished when he stood in front of a chalkboard or in front of the debate team, which he joined despite his reticence.

Muskie always saw both sides to every argument, the kind of guy who went hunting as a kid but would never shoot anything. Chris Matthews, writing in the Sarasota Herald Tribune in 1966, said of Muskie: he “did not enter politics to have his sentences appear in the newspaper … He sought election to make the country better.” So Muskie adopted a tailor’s mien and went to work. Against a resistant president and House of Representatives as well as industry inaction, he was critical in enacting the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act by trying to answer a question he often asked himself: How do you create an environment people can enjoy while protecting it?

WHAT IF… instead of a gravestone-like memorial in downtown Rumford, we host something in praise of Muskie’s deeds? What about celebrating Muskie every year throughout the United States and simultaneously celebrating the natural resources he thought worth preserving, like the rivers and air and trees that were bludgeoned under Paul Bunyan’s axe?

Step 3: The Androscoggin River

Step 3: The Androscoggin River

In the mid 1800s, as small pioneering hamlets up and down the Androscoggin grew into viable municipalities, the populace began furnishing the river with a miasmic and untreated deluge of raw sewage. Log jams, caused by the fury of the river’s spring thaws, dispensed resinous brown sap and bark in the calamity of the push. With all those logs came sawmills, and with sawmills, sawdust slurrying the water and killing off Atlantic salmon. By the start of the twentieth century, factories dominated the banks of the Androscoggin and generated tons of waste, adding to the evolving river cocktail. Upstream and downstream, manufacturers tossed in their dyes, fibers, and toxics. Into the sky went their pollution and particles. Hydroelectric dams impounded natural flow. Plumes from effluent pipes greased the river’s waters. Industry, along with everyone else, believed “the solution to pollution is dilution,” and for a little while, rivers and skies were able to recuperate without aid. Mother Nature, however, could do nothing to remedy what caused the legendary 20-foot walls of urine-colored toxic foam emerging from the canals 40 miles downstream or cure the asphyxiating fallout from the 21 dams that tempered the water and powered the factories.

Years and years of flotsam and effluent choked what fish remained. Aeration dimmed. Water temperature rose. And in 1941 when manufacturing’s concomitant pollution reached a stinky zenith, the smell emanating from the river was so appalling that people fled town or shuttered themselves in. Coins in men’s pockets and silver sets tarnished overnight. Stores closed. House and car paint peeled like burnt skin.

By 1970, when I was three, the Androscoggin’s dissolved oxygen level was exactly zero. Newsweek named it one of the ten filthiest rivers in the United States. Everything in the river died. And when I graduated from high school in 1985, the EPA revealed that Androscoggin fish contained some of the highest dioxin levels in the country.

WHAT IF… in the information booth, pamphlets would outline the path of each toxic that flows downriver, from town to town, and demonstrate how they pick up toxics from other mills, until everything dumps into the sea? What if the rest of the world saw where our toxics go—like into the fish and lobster they put on their dinner plates?

Step 4: Abenaki Silhouettes

Step 4: Abenaki Silhouettes

A black metal diorama of silhouettes representing people from the Anasagunticook tribe of the Abenaki people populates the river’s edge under Bunyan’s shadow and below the Rumford falls. The figures are poised as if fishing for Atlantic salmon— their chief food outside of wild game—in the exact poses a white man may have imagined them to be found. While the Abenaki had fished these waters long ago, by 1700, around 75% of the First Nations people in New England were decimated by disease white settlers brought, driven to the corners of the state or Canada, or killed outright.

The salmon population declined precipitously, too, because of industrial pollution and the accompanying dams (many illegally built without fish passage) that line the river’s banks. The last of the wild salmon were seen suffocating downriver in 1816 because they could no longer spawn upstream with all the barriers in their way; those barriers included the Maine legislature, who did nothing to enforce their laws concerning the safe passage of fish. Atlantic salmon are endangered (and have been since 2000) and are considered an indicator species, meaning they monitor changes in our environment, their health directly affected by ecosystem health. Currently, the only wild populations in the US are found in Maine rivers, albeit not the Androscoggin anymore.

Neither salmon nor Abenaki use the river to maintain their lives today, for it hardly contains any life. The river is still considered Class C, the lowest grade allowed by law in the state. It still contains 14 dams, discharges treated wastewater from our mill, and doesn’t meet the dissolved oxygen levels required for classified higher up the scale.

WHAT IF…we removed those silhouettes, and instead erected an exhibit or memorial that explains the history of the Abenaki, who, at one point (with French Canadians), were the target of a eugenics program in Vermont after the state legalized sterilization in 1931? What if we tell the deeper history of a people who were obliterated from our state because we ripped their food source from a river that we also corrupted with our greed? And as for the salmon, if all the obstacles in their way are removed, they may have a chance to revive and set a precedent for the rest of the United States.

Step 5: Hugh Chisholm

Step 5: Hugh Chisholm

A marble bust of Hugh J. Chisholm, the founder of our mill, welcomes visitors in the first floor of Rumford’s town hall. The town hall is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and its nomination states that the structure “relfects [sic] the aspirations of a community which viewed the future with abounding confidence.” This confidence came from Chisholm himself. And there’s no other person the River Valley lauds as much as him.

Much of our town’s information about and perception of Chisholm were shaped by two books that sit on the shelves in Rumford’s historical society: A History of Rumford, 1774–1972 and The Oxford Story: A History of the Oxford Paper Company, both written by the mill’s public relations man, John Leane. The texts include flattering descriptions of Chisholm: “a visionary” and “driven,” an “indefatigable” man with a “sixth sense.” Leane’s emphasis on the mill’s integral development of the area is on every page. Only two pages, however, of A History of Rumford are devoted to “The Curse of Pollution,” as if our mill’s toxic releases manifested from hell, not the other way around.

“Make the surroundings of the workmen pleasing. If this is done, they will be better satisfied to keep their positions, will take more interest in the town’s success, and make better citizens,” Hugh Chisholm said to the Rumford Falls Times in 1905. In some ways, it wasn’t a bad deal for us to have his enlightened but remote management (he didn’t live in town). It allowed us to feel independent even while we were being cared for by his benevolent control. His mandate to subsidize our lives with a glut of choices in stores, banks, roads, schools, churches, housing, opportunities—to be our guardian, incentivizer, benefactor, boss, town father, authority figure, persuader, and sometime inadvertent oppressor—diverted criticism away from what he earned from our labor and what we lost. While he said his operation wasn’t comparable to “working for the company store,” the debt we paid was far grander: We paid for our work in illness and disease, and in a dependency on his legacy that we can’t quit.

We didn’t realize it then, but we, as part of (not separate from) the industrial complex he built, would lose our benefits and protection when Chisholm or his kin went away. In that, we were like his children, but not the ones written into the will. So when the Chisholms vacated the premises by death or deed, they left a void in the legacy they had so strategically built— a gap that perhaps another big company, like Nestlé Waters, could be all too willing to fill.

WHAT IF… instead of Chisholm’s bust, upstairs in the town hall were records of those he employed? Or what if alongside his bust we listed all the men and women who died under his clock of the cancers his mill produced?

Step 6: Rumford Historical Society

Step 6: Rumford Historical Society

Rumford’s historical society is a wonderful place run by wonderful folks. But their shelves don’t contain much about the men and women who built the mill or worked for Chisholm himself, barring genealogical family trees. What’s in or what’s out of archives has always been decided by those with knowledge or prestige: historians, experts, educators, those with PhDs, public relations personnel, or even modest archivists at small town halls. We depend on these experts to collate and curate the past so the future will know what went on. It’s a powerful profession, more powerful than we sometimes understand, because the facts they choose to memorialize or highlight can be corrupted by motives other than just their job. We are vulnerable, in a way, to their all-seeing eyes, observing and recording history as it unfolds while most of us are just getting through our day. And when history’s makers (like Chisholm) employ (or are aligned with) history’s recorders (like John Leane—see Chisholm site on this map), the resulting output is a skewed artifact all its own.

WHAT IF… River Valley families crafted another kind of record, with stories, audio, video, recipes, photographs, and postcards and letters sent to and fro—ephemera detailing their lives and describing how their ancestors lived and died? I believe the River Valley’s history would be more whole, illuminating a blind spot in our stories that’s not yet been told. I’d hope the resulting archive would balloon and balloon until it would nearly explode. Imagine a marble bust of Uncle Pete? Or a portrait of your mémère? Then, when you step into the archives, instead of a man whose loyalty to this town extended only so far as he could line his pockets with coin from our labor, you’d find shelves full of friends, neighbors, and family, the ones who breathe life—instead of death—into it every day.

Step 7: The Mill

Step 7: The Mill

At the tight bend in the river between Mexico and Rumford, on an island in the Androscoggin, sits the mill’s smokestacks. “That’s money coming out of those smokestacks,” our fathers used to say about the rotten-smelling upriver drafts that surfaced when the weather shifted. That smell loitered amid the softball games we played beneath those stacks and lingered on our fathers’ shirtsleeves when they came home from work, allowing us to forgive the rank odor for what it provided.

While the mill provided livelihoods for many families in the River Valley, it has also released millions of pounds of toxics since it was built. In the last five years alone, 13,558,399 pounds. And what humans are exposed to these pollutants? All of us. But people living in or near factory towns, called “sacrifice zones,” shoulder a heavier burden. Toxics are as local as the people.

In America, the fundamental need for bodies to be respected has always been at odds with industry’s goals. History has shown these abuses to be true, from the coal mines of West Virginia to the paper mills of rural Maine. Regulations that insist humans bear the brunt of the toxics that industry spits into the air is abuse, indeed.

WHAT IF… we installed a device recording and displaying how many toxics are released daily by the mill to the air, water, and land? What would our world be like if we knew what we were doing to our world? What if, too, our federal government enacted a law that insisted we bleach paper using oxygen or peroxide, methods that don’t create dangerous dioxins at all? Or what if our government required all paper-making to use non-toxic processes that produced no environmental problems whatsoever?

Step 8: Farrington Mountain and Olsky landfills

Step 8: Farrington Mountain and Olsky landfills

There are two landfills owned by the mill, and they are in close proximity; one is in operation (Farrington) and one is not (Olsky). The Olsky landfill, just down the road from my old high school and in close proximity to Mexico’s golf course, contains debris from the electrolysis of sodium chloride in a mercury cell process that was done at the mill’s electrochemical plant. The process resulted in asbestos and mercury waste. When the plant was razed in 1979, mercury and polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) debris was stockpiled in the North Mill Yard, i.e. onsite. About four thousand to nine thousand cubic yards of the same debris was trucked to Olsky and some of the mercury-contaminated soil was used as backfill on site. As permitted by the regulations at the time, no liner at the landfill was used to impede the migration of the toxics in the waste.

As a precaution, before the mill’s owners started building a new cogeneration plant on the electrochemical plant in 1982–1983, the EPA required them to test the soil for hazardous waste. Supposedly, nothing worrisome was found. By 1985, Olsky was full. The mill put a lid on it and planted grass over the cap, as if it were never there at all.

In 1990, John DeSalle, who owned a motor inn on the banks of the Androscoggin just downhill from Olsky, wanted to expand, so he drilled another well to accommodate the RVs he anticipated camping on his property. When he hit the water table, up bubbled pea soup. The DEP tested DeSalle’s water and determined that the chemicals in the well were the same chemicals found in Olsky. The mill suggested there could have been another source. The tests proved nothing, they argued. The DEP ultimately agreed. The mill, as a neighborly gesture, built DeSalle a new well and provided bottled water to a few nearby residents. And the pea soup stayed covered up, like so many things in our valley.

In 1995, portions of the cogeneration plant floor built on the former electrochemical plant needed repair. It was jackhammered and tiny beads of mercury clung to the cement chips that flew all around. The mercury, apparently, was just below the surface, not so deep at all, and at levels above the levels it was supposed to have. And when they tested the landfill at Olsky, concentrations of VOCs and elevated levels of mercury were also found. Today, Olsky is in “operation and maintenance” status, according to the EPA, meaning there’s nothing additional to be done except avoid disturbing the napping toxics embedded in the ground. And the mill’s wastes are now dumped in Farrington, which is closed off to the public eye.

WHAT IF… we planted a billboard on Route 2, which is the main road you use to get to either landfill, with arrows pointing to Olsky and Farrington to point out what they contain? Maybe we even enshrine their environmental legacies—the ones buried underneath more attractive designs and façades. “Here lies a toxic catastrophe” would be the first act of acknowledging our environmental crimes. I wonder what kind of festival we’d have for such dangerous shrines as those, or if we’d bother to maintain their perpetual care as lovingly as we shored up Bunyan’s spine?

Step 9: Worker’s Memorial

Step 9: Worker’s Memorial

Local 900 mill union built The Worker’s Memorial to honor members who, instead of going home at the end of the day, died from an accident while on the job. The tribute is made of a retired one-ton drying gear from Number 11 paper machine. The gear, over five feet in diameter, represents several workplace hazards millworkers constantly faced: steam, weight, pinch points, power, and outdated technology such as giant exposed gears.

As offset gears rotated on the paper machines, their steely teeth created pinch points that could result in a crush injury; it would take seconds to lose a finger, an arm, a life. Periodically, the gears needed to be changed, and their rigging and enormous weight present other hazards. (The gear illustrates how much industry has changed; workers are now safeguarded from the machine’s gnashing teeth.) Also, when sixty pounds of steam entered the dryer drum, there’s always a danger of thermal burns.

A former union leader, Ron Hemingway, said about the memorial that everyone represented had perished in an on-the-job accident, but that the deaths memorialized “don’t include the more invisible ones.” Ron died not too long after he made that statement and his name was etched onto the memorial, which begins to admit that the mill caused deaths more indirectly than they admit.

WHAT IF…the memorial included millworkers who died of diseases that could have been from environmental pollutants?

Step 10: Rumford’s Hospital

Step 10: Rumford’s Hospital

Dioxin, cadmium, benzene, lead, naphthalene, nitrous oxide, sulfur dioxide, arsenic, furans, trichlorobenzene, chloroform, asbestos, mercury, phthalates: these are some of the byproducts of modern-day papermaking. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, lung cancer, prostate cancer, aplastic anemia, colon cancer, liver cancer, esophageal cancer, asbestosis, Ewing’s sarcoma, emphysema, cancer of the brain, cancer of the heart: These, I find out, are some of the illnesses appearing in our towns. Occasionally in curious clusters, sometimes in generations of families, often in high percentages.

WHAT IF… the mill’s owner, or the people managing US Superfund monies, created a cancer wing in our hospital so families wouldn’t have to drive to Lewiston or Portland, Maine, to get treatment? A new modern facility would create relief for families who struggle with time, money, and access to the care they need.

Step 11: Acadian Plaque

Step 11: Acadian Plaque

On October 13, 2009, The Acadian Heritage Society installed a plaque near the Rumford public library memorializing Le Grand Derangement (literal translation: the big bother or big disturbance), the period between 1755–1764 when the British ethnically cleansed Acadians (French-speaking residents of the Maritime provinces) from their land for refusing to sign an oath of allegiance to the British.

From about 1840 until 1930, almost a million French-speaking Canadians immigrated to the United States, with the largest percentage going to New England to work in its paper and textile mills. They were the backbone of the industrial revolution, in many ways. Yet growing up in the River Valley, I never knew anything about Acadian history or my forebears, even though so many lived in our towns; the state, the school, our nation had taught us other things.

These are the Acadian families of the River Valley, as noted on the plaque: Allain-Allen, Arsenault-Asrenau, Aucoin, Babineau, Beliveau, Bernard, Blanchard, Boucher, Bourgeois, Boudreau, Breau, Cassie-Roger, Chiasson, Comeau, Cormier, Daigle, Derapse, Deroches, Doiron, Doucet, Dugas, Dugay, Dupuis, Fournier, Gaudet, Gallant-Hache, Gautrot-Goudreau, Gautreau, Girouard, Godin-Gaudin, Goguen-Gogan, Hebert-Henry, Johnson, Landry, Leblanc-White, Legere, Maillet, Martin, Mazerolle, Melanson, Meunier, Miller, Miranda, Morin, Pellerin, Pineau, Pitre-Peters, Poirier-Perry, Prevost, Richard, Robicheau, Roy, Savoie, Surette, Thebault, Therriault, Thibodeau, Turbide, Vignault-Vinneau.

WHAT IF … the Maine public school curriculum insisted on incorporating Acadian history into every syllabus related to our towns, our industries, the working class, our country?

Step 12: Rumford Water District

Step 12: Rumford Water District

In 2017, the Rumford Water District agreed to a 15-year renewable contract with Nestlé Waters, allowing the corporation to extract up to 150 million gallons of water annually (twice the amount Rumford normally uses) from their municipal water supply. Nestlé also hinted at building a bottling plant, which got residents excited about the prospect of lucrative jobs. The company agreed to pay the Water District $200,000–$300,000 per year for those rates and promised to invest in the community.

Data shows that Nestlé has a habit of putting corporate rights over public rights; that trucks increase traffic in rural communities to a detrimental degree; that the company’s products have been boycotted around the world; that drinking from plastic bottles can incur health costs; that bottled water plants wreak havoc on the health of people living near those plants; that such a change in the nature of water use and the volume of extraction is so profound, it merits deliberation beyond data.

WHAT IF… the Maine legislature passed a law that groundwater be held in a public trust, with the reasoning that, like any public resource, it should be publicly owned, not owned by private citizens or corporations. Such a law would ensure public control over a resource that is necessary for life, not corporate bottom lines.

Biographies

is an art director and fine artist based in Roxbury, Connecticut, specializing in visual communication, graphic design, typography, painting, sculpture, and creative thinking. Her mantra is “content drives design.” She has a BFA from the University of Illinois and has continued her study of art and design at Corcoran College of Art and Design, The Smithsonian Institution, Maine College of Art, and George Washington University. She has taught and lectured as a professor of typography and design at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD) as well as the College of Visual Arts in St Paul, Minnesota, and has won awards such as the AIGA’s Fifty Books and Fifty Covers and the Type Directors Club’s Annual Corporate Identity Award.

grew up in the River Valley, and she is a book critic, the book review editor for Orion Magazine, and a contributing editor at Lithub.com. She received her MFA in creative writing from The New School and studied in the graduate program in Communication for Development at Sweden’s Malmö University. Mill Town: Reckoning With What Remains (9/1/20, St. Martin’s Press) is her first book.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.