In the River Valley, a robust culture of “publicness,” let alone public space, seems scant at first glance. This is primarily due to the prominence of the paper mill: Its pollution, smell, optics, and noise make outdoor activities or community gatherings unappealing. For many, however, bodies cannot stay silent or still—even bodies subdued by, dispirited with, or afraid of environmental or work pressures. This two-part feature on public space by writer and literary critic John Freeman and report editor Aaron Cayer examines how bodies can express themselves in small apertures—even when they may be oppressed, restricted, or silenced.

In part II, Cayer’s “Striking Bodies: Aligning Public Spaces” describes the community’s long history of thwarted mill strikes and community protests. He reveals how resistance efforts—and their failures—were results of efforts by corporate powers and governing officials to localize and isolate the community’s concerns for economic gain. His essay considers the agency of protest and organized labor at the present moment, and it explores the possibility of alternative futures that may depend on alliances with intersectional solidarity groups committed to broader terms and geographies of liberation. —Maine’s River Valley report editors

Read part I of the public space feature here.

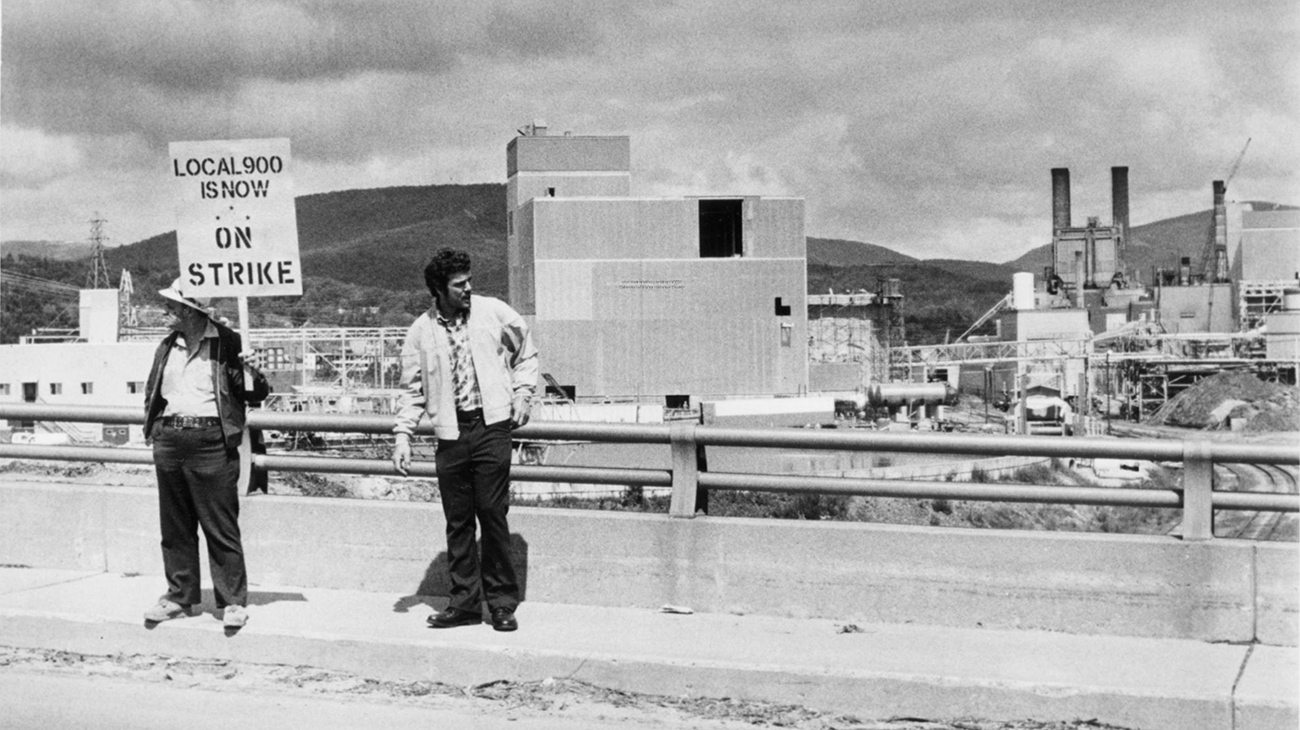

1,200 members of the United Paperworkers International Union on strike at the Boise Cascade mill in July 1980. Right: Joseph E. Thibeault Jr., Left: Henry "Frenchie" Pellerin. Credit: Maine Historical Society. Image courtesy of Aaron Cayer

An analysis of public space in the River Valley reveals longstanding community tensions and a schism between local and global bodies. Immigrant families moving to the region in the early 1900s found comfort in congregating locally. Defined by the disciplining power of the paper mill, they expressed, moved, protested, and prayed together, and they became attached to “place”: to the River Valley, to the mill, and to a knowable community defined and defended as “ours.” Yet as neoliberal policy and postindustrialization enabled corporations such as the mill to expand outward in pursuit of greater profits, a powerful stratum of other bodies grew capable of reaching across spaces, disconnected from place. Corporate heads of the mill (most recently, the China-based Nine Dragons Paper) were severed from the mill’s laboring bodies in Maine, just as the pulp and paper produced by the mill was circulated globally as the company’s public stock. Since the 1980s, even the strongest local unionizing efforts, the most coordinated environmental activists, and the loudest community voices have not been enough to overpower the profit-seeking powers that have descended on the community.

This article considers the agency and spaces of local labor organizing in the River Valley, as well as the ways in which the schism between global and local was historically constructed. The public spaces through which the paper mill’s capital flows, such as the New York Stock Exchange, reveal a radically different story of ambition than the public spaces of local strikes and protest. Profits and global investments by the mill were not only increasingly detached from place, but their growth was also predicated on focusing the local working-class public inward by insulating protests, containing and regulating public spaces, and suppressing class consciousness. The result: a divided working class, a tolerance of precarious labor practices, and a perception that resistance is futile.

Timeline of the River Valley

- 1779: Township granted, named “New Pennacook Plantation”

- 1800: Town of Rumford incorporated

- 1826: Mineral spring business founded at Mount Zircon

- 1901: Oxford Paper Company established

- 1902: Strathglass Park, designed by Cass Gilbert, constructed for worker housing

- 1903: First worker strike at Oxford

- 1908: Paper companies in River Valley and Northeast US strike

- 1921: Paper companies across US strike; workers lose homes, jobs, and union membership declines

- 1967: Ethyl Corporation purchases the paper company

- 1976: Boise Cascade purchases the paper company

- 1980: Worker strike at Boise Cascade

- 1986: Worker strike at Boise Cascade; workers permanently replaced

- 1987: Worker strike at International Paper in nearby Jay; workers permanently replaced

- 1991: River Valley christened as “Cancer Valley”

- 1996: Mead Corporation purchases the paper company

- 1998: Forestry industry-sponsored study of paper mill mortality published; proves “inconclusive”

- 2005: NewPage purchases the paper company

- 2011: Maine Governor Paul LePage removes Maine labor history mural from State Labor Department

- 2015: Catalyst Paper purchases the paper company

- 2018: Nine Dragons Paper purchases the paper company

- 2019: Poland Springs (Nestle) begins drilling for water in Rumford

For a community whose land was shaped by the successive forces of colonization and industrialization, the River Valley’s public space has been and continues to be largely defined by the paper mill, which once held the rights to much of the community’s land, housing, and government buildings. Worker confrontation, such as labor strikes and protests, emerged largely from interstitial spaces, including parking lots, sidewalks, fields, and streets, instead of bona fide public plazas, squares, or parks. Since the mill’s beginning, some of the most widely cited, studied, and published stories about the community depict moments of solidarity between mill workers and their immigrant families as they stood up to capitalists, environmental threats, and racist hate groups—even when their collective voice was not quite loud enough to produce alternative futures. Local actions ranged from labor strikes of unionized mill workers to protests against KKK members who paraded through the River Valley to recruit. More recently, protests formed against global food conglomerate Nestlé, which has invaded the region in order to drill and profit from the natural spring water once cherished by the land’s Indigenous people.

Mill Strikes and Declining Union Power

The River Valley was developed on land once traversed by the Anasagunticook people, who lived along the banks of the Androscoggin River and at the base of the river’s waterfall—sites that are now protected as part of the National Register of Historic Places.1“Town of Rumford Site,” Rumford, ME, National Register of Historic Places, ref. 92001507. In the same valley, Canadian-American industrialist Hugh J. Chisholm purchased 1,200 acres of land from 132 individual landowners in order to develop the Oxford Paper Company and other mills in the town of Rumford.2Morrow, “Hugh J. Chisholm, Head of the ‘Paper Trust,’ Plans Industrial School for Workingmen’s Children.” Unlike much of the land in the western states of the United States, which is predominantly publicly owned, land in Maine is largely held by private industrial owners.3Beckley, “Pulp, Paper and Power,” 133. There, paper mills were central actors in nearly every decision about land use. In addition to the Oxford Paper Company, earlier in 1898 Chisholm formed the International Paper Company (IP), a corporate organization of 17 paper mills, including one in Rumford. While Oxford Paper outlived IP in Rumford, IP has gone on to become the largest paper company in the world and was once the largest private landowner in the nation.4Ward, “A Clearing in the Forest.”

Class-based hierarchies were embedded in the social structures of the mills, as well as in the community’s public spaces and landscapes and the labor unions’ policies. These hierarchies provided a foundation of social divisions in the town that fueled protests and strikes: capitalists vs. laborers; immigrants vs. nonimmigrants; skilled vs. nonskilled workers. Skilled workers were lured primarily from Massachusetts and New Hampshire with a promise of high wages, secure housing, and profit-sharing plans, while lower-waged positions and more precarious jobs were filled predominantly by French-Canadians from Quebec, as well as some workers from Italy and Poland. These hierarchies blocked many immigrants from advancing into the ranks of management during the early twentieth century, leading to bitter rivalries between union organization and leadership. Early paper mill unions represented the “fraternal solidarity of skilled craftsmen,” while immigrant workers were often denied charters; in Jay, Maine, for instance, the “Brotherhood,” or the International Brotherhood of Paper Makers (IBPM), pressured the American Federation of Laborers to deny union charters for immigrant workers.5Carbonella, “Labor in Place/Capitalism in Space,” 89.

“Maine Timberlands” from Oxford Log, 1964. Credit: Rumford Historical Society. Image courtesy of Aaron Cayer and Kerri Arsenault

In 1903, only two years after the Rumford mill was formed, the workers at Oxford went on strike after a colleague was unfairly fired and replaced, establishing an early precedent that organized workers held bargaining power. By 1908, workers at three of Rumford’s mills went on strike in solidarity with their counterparts at mills across the Northeast, as owners launched all-out attacks on unions. At the Oxford Paper Company, nearly 900 hourly workers mobilized in spaces around the mill after demanding a new system of shifts—one shift of ten hours rather than three shifts of eight—and a 5 percent increase in wages. In retaliation, the company eliminated 140 people, including the president and vice president of the two leading local unions. Following the strike, workers at Oxford were required to sign a pledge in order to return to their jobs. It stated: “I am not a member of any labor organization, and while I remain in the employ of said Company, agree not to join any labor union, directly or indirectly.”6Beckley, “Pulp, Paper and Power,” 99. At both the IP and the Oxford Paper Company, organizing efforts were thus thwarted, though the unions were formally recognized again soon after.7“Strike at a Paper Mill,” 2.

In 1921, when there were four paper mills in Rumford, all founded by Chisholm, workers joined nearly 10,000 papermakers across the United States to protest proposed reductions in wages and expanded scopes of work. Concessions were made for skilled laborers, but the strike lingered until 1926. Permanent replacement workers were called in, and many of the original workers lost their homes. Union membership declined, and the strike was ultimately called off. The unions were no longer recognized by the mill owners.8Beckley, “Pulp, Paper and Power,” 144.

At the Oxford Paper Company, the union was not officially recognized again until 1933—the same year that the company raised wages and instituted a 40-hour work week rather than risk a strike.9Beckley, “Pulp, Paper and Power,” 133. Between the 1940s and 1980s, the unions were well established in Rumford, maintaining collective organizing power, and strikes did not usually last long. During strikes, a mill would be unable operate properly, causing owners to shut it down; the union and managers would then negotiate, and a new agreement would emerge.

The lines of division between workers remained deeply entrenched, however, even as the history of the 1908 and 1921 strikes in the region faded from public memory. Workers across the line of paper production remained in silos—silos that were reinforced by local unions. While mill workers were unionized, many service workers, loggers, truck drivers, salaried workers, and mill managers were not. In 1980, 1,200 unionized workers at the mill—then owned by Idaho-based Boise Cascade—went on strike. Workers argued that their contract did not fully address pension and insurance issues or include raises at satisfactory rates. Unlike before, however, the union no longer held enough organizing power to shut down the mill. Instead, salaried employees kept the business running, and owners invited additional workers from nearby mills to join. They also hired security guards and sealed off the perimeter of the mill.

In the strike’s early days, Boise refused to compromise. Striking workers responded by picketing at the entrances, preventing pulp trucks from delivering wood; some even fired shots into the mill to damage machines. But in the end, the workers still managed to win.

By 1986, however, the power dynamics had begun to change. Union members went on strike in July, as the mill’s owners tended to global spaces of capital accumulation by broadening the scope of work for most employees in order to increase profits and public share value. The owners refused to negotiate with the striking workers. Unable to fully operate with only salaried employees, they hired permanent replacement workers. The strike both splintered the River Valley and demonstrated that the longstanding social agreement between mill owners and mill workers was no longer valid.

Political Paradoxes of Organizing

Under the union-busting presidency of Ronald Reagan, the 1980s proved to be a major turning point in the history of organized labor across the United States, and especially in Maine’s rural industrial communities. During Reagan’s first term, paper companies launched suffocating restrictions on workers’ rights, attacked their pay, and hired permanent replacement workers—a practice granted by law in 1964, though infrequently used until the 1980s. In Maine, the conflict peaked in 1987, when workers went on strike at International Paper in the town of Jay, nearly 30 miles from the River Valley. After a record-setting year of profits, they were supplanted by over 2,200 permanent replacements.10On the IP strikes, see: Early, “Solidarity Sometimes;” Dannin, “Divided We Fall;” and Minchin, “‘Labor’s Empty Gun’.”.

The strikes at the paper mills in the River Valley in particular—and at mills more generally—have been studied by historians, sociologists, anthropologists, and others who argue that their failure represented the beginning of a long downward spiral of union power.11 See, for example: Carbonella, “Labor in Place/Capitalism in Space;” Minchin, “Broken Spirits;” and Beckley, “Pulp, Paper and Power,” 133. While union membership declined during the 1920s, it plummeted even more dramatically across the country beginning in the 1980s, declining from 23 percent of the workforce in 1980 to 16 percent in 1990. This shift has continued: 13 percent of the workforce was unionized between 2000 and 2010, 11.9 percent in 2010, and 10.5 percent in 2018.12US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union membership rate 10.5 percent in 2018.”

Many of these union-busting practices have regained momentum in the twenty-first century. President Trump directed the National Labor Relations Board to scrutinize labor unions just as US Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta (2017–2019) announced that Reagan would be inducted into the agency’s Hall of Honor.13US Department of Labor, “US Secretary of Labor Acosta Announces the Upcoming Induction of President Ronald Reagan into the Department of Labor Hall of Honor.” In Maine, Republican governor Paul LePage (2010–2018) similarly fought against labor unions, including the state employee union, and, perhaps more controversially, by removing an 11-panel mural by artist Judy Taylor depicting Maine’s labor history from the lobby of the state’s Labor Department in 2011. LePage argued that his “pro-business” agenda was at odds with the mural and cited public complaints, including one arguing that the mural evoked an image of “communist North Korea, where they use these murals to brainwash the masses.”14Epstein, “Maine Governor Removes Labor Mural;” and “He Dreamed He saw Kim John-il.” The two final panels in the mural series (image below) represented the “The Strike of 1987” at the International Paper Company and “The Future of Maine’s Labor”—the latter of which depicts a worker from the past offering a hammer to perplexed workers of the present. Together, the murals suggest that 1987 was a penultimate moment of labor organizing in Maine. Like the overpowered strikers of the 1980s, the removal of the mural confirms impossibility, since it suggests that labor discourse, labor organizing, and the history of Maine’s workers was to be removed from public space altogether.15In January of 2013, the mural was moved the Maine State Museum, where it is currently installed, framed by the museum now as artifact, rather than as a public memory. However, the controversy about the mural’s removal paradoxically pushed discourse about class and labor into the foreground of public attention.16Carbonella, “Labor in Place/Capitalism in Space,” 131.

Judy Taylor, “The Strike of 1987” (left) and “The Future of Labor in Maine” (right), 2008. Currently on display at the Maine State Museum. Images courtesy of Judy Taylor

While LePage’s removal of the mural purported to reflect his support for Maine business owners, in paper mill communities such as the River Valley, non-local corporate interests were prioritized over those of local workers— at the time, the mill was owned by an Ohio-based company, NewPage. Ironically, while the River Valley, a community of laborers, historically backed campaigns of pro-union elected officials, this dramatically changed in 2010. In 2010 and 2014, the majority of residents in Rumford supported a Republican candidate for the first time in decades and voted for LePage, who won 53% of the local vote in 2014 and 39% in 2010.17In 2014, 53% of Rumford residents voted for Republican governor Paul LePage, and in 2010, 39% supported him. Similarly, 52% of voters in Oxford County, in which the River Valley sits, voted for Donald Trump in 2016.18“2016 Maine Presidential Election Results.” In other words, not only was the agency of labor unions in the region challenged, but the workers were supporting the very politicians responsible for their own precarity.

A Strike that Divided

In Rumford, the strike of 1986 was perhaps the most memorable and widely studied. Shortly after Boise Cascade purchased the paper mill from the Ethyl Corporation19Ethyl, which purchased Oxford in 1967, was the first non-local owner since the mill’s 1901 founding. in 1976, union members argued that Boise was more interested in corporate interests and a global public than in the livelihoods and wellbeing of the local workers. During new contract negotiations, Boise proposed reducing overtime and vacation pay, eliminated traditional holiday shutdowns, and suggested reducing the average worker’s salary by nearly $2.00 per hour.20Minchin, “Broken Spirits,” 9. As a result, nearly 94 percent of the Local 900’s membership rejected the company’s contract. Production rates fell immediately, as the mill could not function properly with salaried workers only, and Boise developed an extensive plan to recruit, hire, and house replacement workers. Violence ensued. Like the strikes in 1921, picketers crowded the mill’s entrances and parking lots; guns were fired at homes and into the mill. Meanwhile, “scabs”—those hired as replacements—crossed the picket lines and went to work.

As the mill’s owners refused to budge, the replacement workers began to pose a serious threat to the union. Under United States labor law, if more than 30 percent of the workforce petitioned the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which Reagan used as a mechanism to stifle labor unions while he deregulated big business, the union could hold a new election. And if a majority of workers voted against the union, it could be decertified and denied its bargaining rights. Realizing that the mill’s management was not about to change its mind, and worried that all might eventually be replaced, the union re-voted to call off the strike after 342 jobs were filled by replacement workers, and the workers accepted the contract they had so strongly opposed.

Kerri Arsenault (co-editor of this report) recalls the scene in her recent book Mill Town, describing the ways in which the spaces of protest blurred the lines between public and private space and pitted worker against worker:

It was scab versus non-scab; you sided with the union or else. Picketers howled at logging trucks and banged on hoods of scabs’ cars as they slithered through the mill’s main gates. People vandalized homes. Neighbors fought toe-to-toe. Cars got keyed. Heads were bashed. A roustabout even fired gunshots. Some of the more harrowing battles, however, arose outside the picket line and in our homes; old friends became new enemies and family reunions and holidays collapsed all over town. At night, men and women gathered at the unofficial strike headquarters, the Hotel Rumford, for beer and blackballing super scabs, a special designation for millworkers who went on strike and returned to work during the strike, but in someone else’s job … Boise’s contempt for such loyalty infuriated millworkers who, before the strike, always felt a neighborly regard for their employer and were given a say in collective bargaining. Suddenly they were being told what to do. My father believed Boise didn’t want to negotiate in good faith because a broken union and a flexible workforce would grant Boise the upperhand in any future contract discussions. Yet millworkers thought they had the upper hand: they knew how to run that mill better than any of the absentee owners or the corporate supervisors who had flown in from around the country.21Arsenault, Mill Town: A Reckoning with What Remains, 167.

Even after the strike, the community remained divided. Many scabs hoped to keep their new and high-paying jobs, while many houses were still attacked. Several national newspapers took note of the strike, including The New York Times, which described Rumford as a “deeply troubled community, so wounded in spirit that many residents believe it will take years, possibly generations to heal.”22“Maine Town Divided by Bitter Strike.”

“Militant Particularism” in the River Valley

The photos of the union members on strike and the spaces they occupied during the 1980s depict scenes of worker-to-worker friction that reproduced the longstanding divisions embedded in the foundation of the community, the mill, and the labor organizations. The caption of a 1980 photo (image above), for example, reads: “Picketers here at the Boise Cascade paper mill move slowly out of the way of a large pulp truck trying to deliver a load of pulp to the mill here. About 1,200 members of the United Paperworkers International Union struck the mill, 7/1, when they rejected a proposed contract offer. Nine strikers were arrested, 7/28, when they attempted to block trucks delivering loads to the struck plant.” In the photo, men and women of the local union stand clustered casually at the mill’s trucker entrance with freshly chipped wood as their backdrop. Two raise their fists in threatening solidarity while they attempt to thwart routine mill production. While the clanking bulldozer pushes wood chips and the mill continues to operate in the background, the workers stand in opposition—not to Boise owners or corporate supervisors, but to workers in similarly precarious and marginalized positions. In further irony, the workers stood against the independent pulp driver from P.M. Chadbourne & Co.—an independent company awarded the Austin H. Wilkins Stewardship Award by Republican governor Paul LePage in 2014 for conservation achievements.23In 2014, Governor LePage awarded the Chadbourne Tree Farms Company the Austin H. Wilkins Stewardship Award, which “recognizes people or organizations that stand above their peers to further forestry, forests, or forestland conservation in the state of Maine.” These worker-to-worker oppositions presented divisions within the full line of paper production that served to benefit Boise. The company’s corporate owners flying in from Idaho mirrored the equally fluid movement and spatiality of the mill’s public stock, which by the end of the 1950s was held by shareholders in all 50 states and over 30 different countries—all while the working-class political animosity remained local and thus embedded in the “place.”

In his description of the labor strikes at the International Paper Company in Jay in 1987, anthropologist August Carbonella has argued that they served as a testament to the United States’ model of Fordism, characterized by localism and isolation, that was not only embedded in rural industrial production, but also in union laws and policy.24Carbonella, “Labor in Place/Capitalism in Space,” 77-122. Carbonella suggests that, as in Rumford in 1986, the encoded localization and enforced isolation of paper mills in Maine has led to union defeats, and that the union workers did not fully address the neoliberal project of capitalists as a whole: “their failure to attempt the mobilization of all workers in the forest industry—from the precarious wood workers, to the independent wood haulers, up to the highest-paid machine tenders—registered the lingering influence of the US labor movement’s political insularity.”25Carbonella, “Labor in Place/Capitalism in Space,” 118. Business supporters in public office, as well as the nation’s labor laws, encouraged the spatial insularity of local protest in order to encourage new forms of global neoliberal investment, he argued, and in so doing, they permanently disorganized the working class and secured precarious labor practices.26Carbonella, “Labor in Place/Capitalism in Space,” 118.

With declining union membership and no formal worker resistance since 1986, labor precarity has continued in Rumford—impacting even those most central to labor organizing. In 2017, for instance, the mill’s longtime President of the Local United Steelworkers Union, Ron Hemingway, died from mesothelioma—a form of cancer that paper mill workers are at high risk of developing—while the community became known nationally as “Cancer Valley.”27Hemingway began representing workers in the mill in 1980 and later held state and regional positions, including President of the Main Labor Council and President of the Region 1 Labor Council.

A parallel story about Cowley, a factory town in East Oxford, England, is particularly illuminating. In their Factory and the City, David Harvey and Theresa Hayter describe how workers at the local Rover car plant mobilized during the 1980s as the plant shrunk from 27,000 employees in the 1970s to 10,000 in the 1980s, then to 5,000 by 1993. The authors describe the history of Cowley, the workers’ failed campaign, and the political challenges of resistance to corporate capital.28Harvey and Hayter, The Factory and the City: The Story of the Cowley Automobile Workers in Oxford.

In later writings about the events, Harvey draws on Raymond Williams’s concept of “militant particularism” to argue that local actions (including union strikes) bound to a specific place and focused on one particular labor concern (such as wages) would not be able to amass enough power until they moved from particular (local) grievances to more abstract (global) ones by uniting with other worker campaigns. Only together, he argues, could a collective group of allied workers combat the global flow and spatial dominance of global capitalists.29Harvey and Williams, “Militant Particularism and Global Ambition,” 80. In short, Harvey suggests that it is only through the large aggregation of individuals, such as those connected to working-class struggles in other industries or cities, or along an entire line of production—from the site of extraction to the site of consumption—that workers might achieve alternatives.

Yet how might local workers push against the immense localizing pressures of global capital accumulation in order to recognize the broader spatiality of their struggle and allied campaigns? In his Resources of Hope, Raymond Williams describes how alternative futures were rendered possible when local workers saw firsthand how their struggles related to others’—in the case he describes, striking miners nearby—and began to understand how the local spaces in which they lived were connected to the more abstract spaces through which goods, people, and information circulated:

These men at the country station were industrial workers, trade unionists, in a small group within a primarily rural and agricultural economy. All of them, like my father, still had close connections with that agricultural life … At the same time, by the very fact of the railway, with the trains passing through, from the cities, from the factories, from the ports, from the collieries, and by the fact of the telephone and the telegraph, which was especially important for the signalmen, who through it had a community with other signalmen over a wide social network, talking beyond their work with men they might never actually meet but whom they knew very well through voice, opinion and story, they were part of a modern industrial working class.30Williams, “The Social Significance of 1926,” 1065-6.

For Williams, the strike represented a crucial step in the realization of class consciousness, as well as in the imagining of alternative possibilities. In his reading of the book, Harvey suggests that local realizations were “arrived at precisely through the internalization within that particular place and community of impulses originating from outside.”31Harvey, “Militant Particularism and Global Ambition,” 81. Therefore, the raising of political consciousness in the River Valley may similarly rely on new relationships between mill workers and allied networks of labor, environmental, or racial justice, as well as on new means by which the region’s support of global production and exchange can be rendered visible.

Conclusion: Outside In

During the International Paper Company strikes of 1987 in Jay, union leaders fought desperately to widen the scope of their organizing to include a more general and powerful movement demanding social and economic justice for the working class. Their solidarity network ranged from laundry workers to roofers to plumbers, and union members filled all of the vacant seats of the town’s council. They developed a movement that operated across spaces and challenged postwar geographies as well as the localisms enforced by the union. Even still, these networks were not expanded enough, and mill workers were replaced.

While the history of the River Valley makes visible the ways in which a local sense of belonging was socially and materially encoded, it also begs the question: What kinds of allied efforts of liberation might intersect with the politics of a working-class mill town? The River Valley’s own history begins to reveal how union policies and capitalist pursuits operated not only by maintaining hierarchies of class tied to land and labor privilege, but also racist hierarchies of citizenship and belonging. A year after the 1986 strike, white-robed and hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan paraded through the River Valley and through the Rumford High School auditorium—an event that culminated with the public burning of a 20-foot cross on the outskirts of the town. As an organization predicated on white supremacy, anti-Catholicism, and anti-unionism, the KKK hoped to recruit members in the mill town after the failed strikes.32“Demonstrators jeer Klan at Maine rally.” The parade’s leader, James W. Farrands, the head of the Invisible Empire, Knights of the KKK from Connecticut, argued that the national media reports of violence and failed union efforts in the region signaled that locals would be receptive to recruitment.33“Rally Site Quiet Again; Klan Leader Vows to Return.” Yet nearly 300 protestors in the French-Catholic immigrant town gathered to denounce the KKK (image below), raising signs and fists in solidarity—many of the same bodies and raised fists that had gone on strike a year prior at the mill—in order to fight against all that his group represented.

The arrival of the KKK in Rumford was fueled by animosity toward unions that preceded the 1980s in certain parts of Maine. The KKK surged during the 1920s as well, following the First Red Scare and the failed International Paper union strikes—when small immigrant mill towns like Rumford stood out amongst the otherwise white and homogenous Protestant towns in New England. Members of the KKK were fueled by an anti-black agenda in the south, and they were motivated by an anti-French Catholic agenda in the north. It was these immigrants who the group blamed for stealing jobs and contaminating white culture.34See: Leary, “Cities in Maine Rally Against the Klan;” and Leary, “How the KKK Helped Elect A Maine Governor”

These parallel stories reveal just how deeply race and class are interwoven in American communities—united by histories of labor, immigration, exploitation, extraction, precarity, and racism. When viewed through an intersectional and historical lens, labor organizations such as the local union in Rumford may find greater alliances with environmental and abolitionist solidarity networks. While the earliest of unions in the United States, and even the earliest Marxist philosophers, distanced themselves from abolition campaigns and failed to fully examine the ways in which racism was a founding tenet of American capitalism, many powerful alliances between the civil rights movement and the labor movement have emerged over the course of the twentieth century and demonstrate the effectiveness of intersectional and trans-regional solidarity.

Powerful bodies continue to descend upon the River Valley in search of resources to extract and exploit, meeting still-localized resistance efforts of insulated protest that they overpower. Most recently, community members took to the streets in 2016 with their familiar fists and signs in the air to fend off the global food conglomerate, Nestlé, which has viewed the town’s natural spring water as an opportunity for bolstering its Poland Springs drinking water subsidiary, which began in Maine. Historically, the region’s spring water was as cherished as its forests: even prior to the founding of the paper mill, the River Valley’s springs were regionally celebrated for their purity and, according to local legends, their healing properties. In the end, the results of public resistance mirrored the failed strikes of the 1980s and the triumph of capital over on-the-ground community protest: despite opposition, Rumford town officials agreed to allow Nestlé to drill water in exchange for funding support to upgrade the town’s aging infrastructure.

The history of failed labor strikes and protests in the River Valley reveals how worker struggles are often wiped away and forgotten, the lessons learned from each event going unheeded. But history lives on silently in the present—embedded in the public spaces and the “place”—and in the next generation of workers who carry forth the legacy of labor organizing, as well as in the vision of neoliberal capitalists who continue to seek global dominance at all costs.

As Raymond Williams reminds us, the materials and spaces of the present hold and represent the past. “Press your fingers close on this lichened sandstone,” he writes. “With this stone and this grass, with this red earth, this place was received and made and remade. Its generations are distinct but all suddenly present.”35Williams, People of the Black Mountains: The Beginning, 2. As a community of immigrants and committed laborers, the past provides insights into the region’s possible futures.

Biographies

PhD is an architectural historian and assistant professor of architecture history at the University of New Mexico. He was raised and educated in the town of Rumford, Maine—the largest of those within the River Valley. He left Rumford for college after graduating from Mountain Valley High School. Cayer studied architecture at Norwich University in Vermont, where he earned undergraduate and graduate degrees, as well as at UCLA, where he received his PhD in architecture history.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.

Select Bibliography

Arsenault, Kerri. Mill Town: A Reckoning with What Remains. New York: St. Martin’s, 2020.

Beckley, T.M. “Pulp, Paper, and Power: Social and Political Consequences of Forest-Dependence in a New England Mill Town.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1994. https://books.google.com/books?id=FpBpAAAAMAAJ.

Carbonella, August. “Labor in Place/Capitalism in Space: The Making and Unmaking of a Local Working Class on Maine’s ‘Paper Plantation.’” In Blood and Fire: Toward a Global Anthropology of Labor, edited by Sharryn Kasmir and August Carbonella, 77–122. Dislocations, volume 13. New York: Berghahn Books, 2014.

“Chadbourne Tree Farms receives Austin Wilkins Award.” Maine Forest Products Council, 2014, accessed January 27, 2021. https://maineforest.org/chadbourne-receives-2014-austin-wilkins-award/.

Dannin, Ellen J. “Divided We Fall: The Story of the Paperworkers’ Union and the Future of Labor (review).” Labor Studies Journal 31, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 96-97. https://doi.org/10.1353/lab.2006.0006.

“Demonstrators jeer Klan at Maine rally.” Chicago Tribune, September 28, 1987: 32.

Early, Steve. “Solidarity Sometimes.” The American Prospect, November 9, 2001, accessed January 27, 2021. https://prospect.org/features/solidarity-sometimes/.

Epstein, Jennifer. “Maine Governor Removes Labor Mural.” Politico, March 28, 2011, updated March 29, 2011, accessed August 3, 2020. https://www.politico.com/story/2011/03/maine-governor-removes-labor-mural-052050.

Harvey, David, and Theresa Hayter. The Factory and the City: The Story of the Cowley Automobile Workers in Oxford. London: Mansell, 1993.

Harvey, David and Raymond Williams. “Militant Particularism and Global Ambition: The Conceptual Politics of Place, Space and Environment in the Work of Raymond Williams.” Social Text 42 (Spring 1995): 69-98. https://doi.org/10.2307/466665.

“He Dreamed He Saw Kim Jong-il.” New York Times, March 27, 2011, accessed August 3, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/28/opinion/28mon4.html?partner=rss&emc=rss.

“How Maine voted: Governor’s races 1990-2014.” Interactive content. Portland Press Herald, 2014, accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.pressherald.com/interactive/maine-voted-governors-races-1990-2010/.

Leary, Mal. “Cities in Maine Rally Against the Klan.” New York Times, September 27, 1987: 26.

Leary, Mal. “How the KKK Helped Elect a Maine Governor—The State’s Long History with Hate Groups.” Maine Public Radio, August 30, 2017, accessed August 1, 2020. https://www.mainepublic.org/post/how-kkk-helped-elect-maine-governor-states-long-history-hate-groups.

“Maine Town Divided by Bitter Strike.” New York Times, December 28, 1986: 36.

Minchin, Timothy J. “’Labor’s Empty Gun’: Permanent Replacements and the International Paper Company Strike of 1987–88.” Labor History 47, no. 1 (February 2006): 21-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00236560500385892.

Minchin, Timothy J. “Broken Spirits: Permanent Replacements and the Rumford Strike of 1986.” The New England Quarterly 74, no. 1 (March 2001): 5-31. https://doi.org/10.2307/3185458.

Morrow, James B. “Huge J. Chisholm, Head of the ‘Paper Trust,’ Plans Industrial School for Workingmen’s Children.” Washington Post, September 6, 1908: SM1.

“Rally Site Quiet Again; Klan Leader Vows to Return.” Associated Press, September 28, 1987, accessed August 1, 2020. https://apnews.com/article/72d888f9fcd114db459e74aacb0d1591.

“Strike at Paper Mill.” New York Times, November 17, 1908: 2.

“Town of Rumford Site.” National Register of Historic Places, ref. 92001507.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Union membership rate 10.5% in 2018.” January 25, 2019, accessed August 1, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2019/union-membership-rate-10-point-5-percent-in-2018-down-from-20-point-1-percent-in-1983.htm?view_full.

US Department of Labor. “US Secretary of Labor Acosta Announces the Upcoming Induction of President Ronald Reagan into the Department of Labor Hall of Honor.” August 24, 2017, accessed August 2, 2020. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/osec/osec20170824.

Ward, Sandra. “A Clearing in the Forest.” Barron’s, June 30, 2012. https://www.barrons.com/articles/SB50001424053111904317504577490881599719796.

Williams, Raymond. “The Social Significance of 1926.” In Resources of Hope: Culture, Democracy, Socialism, edited by Raymond Williams, 1065-1066. London: Verso, 1989.

Williams, Raymond. People of the Black Mountains: The Beginning. London: Paladin, 1990.