Brownsville, Texas

Brownsville Undercurrents

Lizzie MacWillie, Kelsey Menzel, Jesse Miller & Josué Ramirez

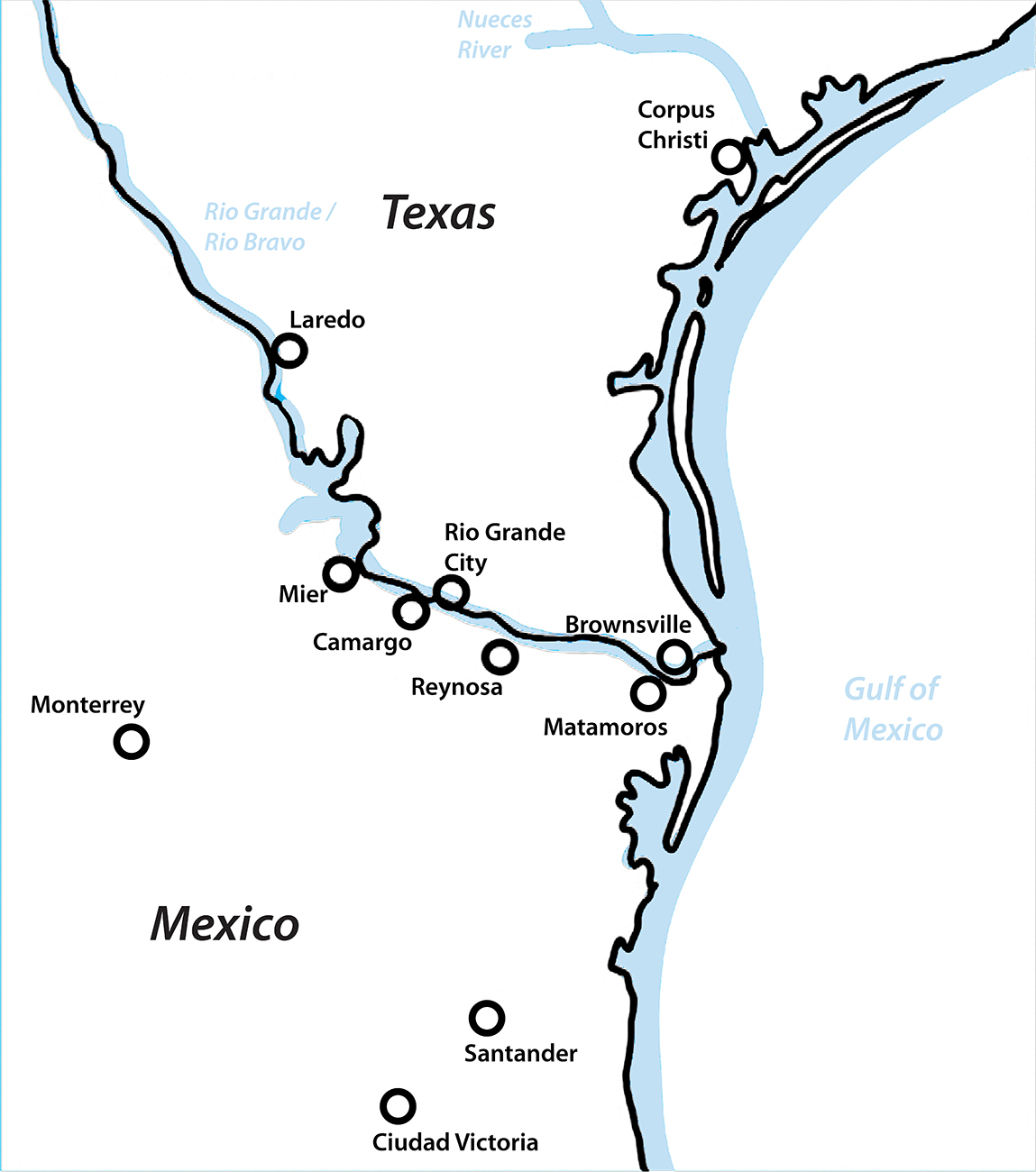

Brownsville, Texas, the southernmost American city on the US–Mexico border, is located on a bend of the Rio Grande, across from Matamoros, Mexico, and 20 miles from the Gulf of Mexico. The city lies in what is called the Lower Rio Grande Valley, although it’s not really a valley, but rather a delta created by movement of the river and its channels as it empties into the Gulf.

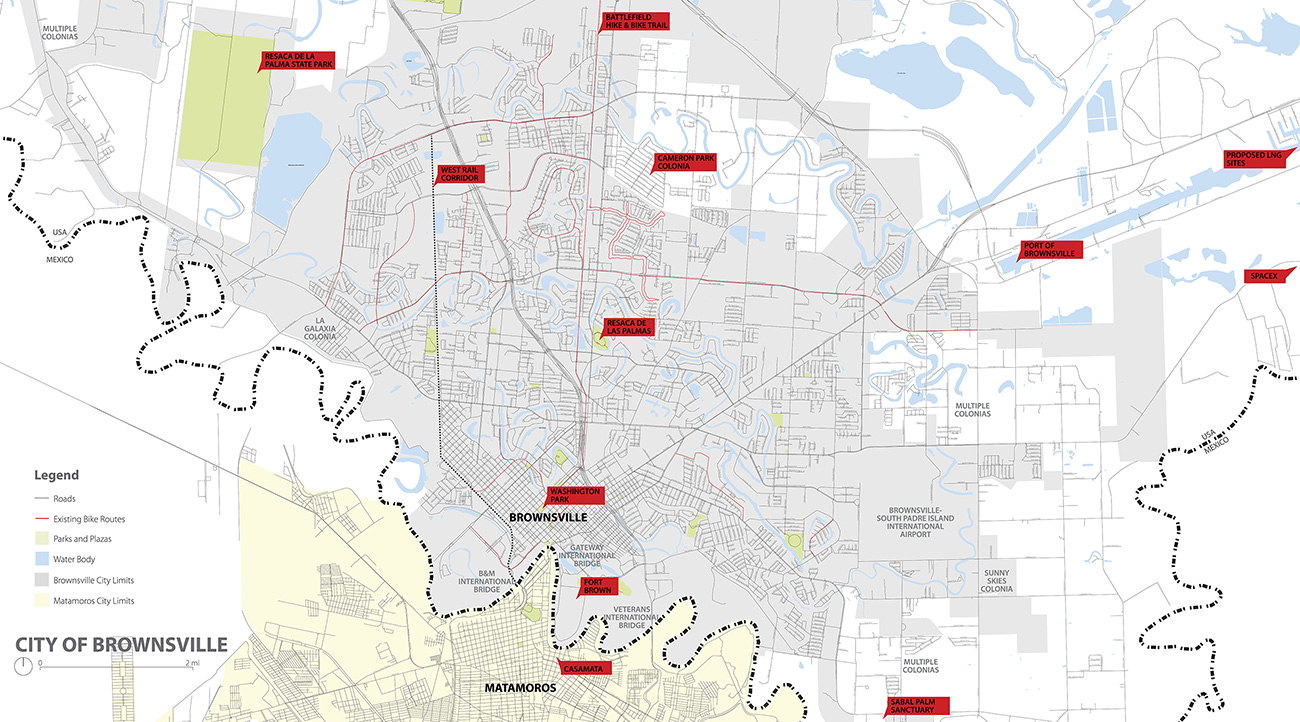

The geography and geology of the Valley, which has clayey soil that does not absorb water well, make the area prone to flooding. But as a delta region, this soil is also rich, allowing a wide variety of plants to thrive, especially around Brownsville’s resacas, or channels of water that were formed when the river would naturally overflow before it was engineered.1“Lower Rio Grande Valley: Water Management,” US Fish and Wildlife Service, Accessed November 28th, 2020. These natural features become more evident as you move outward from downtown, which is located immediately adjacent to the Rio Grande and a border crossing into Matamoros. The downtown core is a dense urban grid, which consists mainly of one- and two-story commercial buildings. The brick used for these historic buildings, most dating to the 1800s, features light yellow and russet hues, evidence of the region’s complex clay soils.

Moving away from downtown the grid changes, becoming less dense as it becomes more residential. It kinks as it intersects with resacas, highways, and the border, eventually dissolving into a suburban network of superblocks and cul de sacs.

Today, Brownsville is making headlines due to increased national attention on immigration and for the human rights abuses committed at ports of entry and detention centers: major employers in the city. But Brownsville is also a city like any other, with residents traveling to and from work, raising families, and completing other everyday tasks in this “Borderplex.” It is a beautiful place where visitors come for ecotourism like bird watching at Resaca de la Palma World Birding Center or Sabal Palm Sanctuary, both stopping points for migrating birds.

Recently, projects including new trails, greenspaces, and a performing arts center have been built in downtown Brownsville. And in 2014, Elon Musk chose nearby Boca Chica beach as the launch site for SpaceX, which has placed a new spotlight on the region. While truly notable, the benefits from these developments are not experienced equally by all residents. As is the case in many other American cities, Brownsville’s economic growth continues to be grounded in systems and patterns of structural inequity. These systems and the trauma they inflict not only hinder opportunities for many residents, but actively benefit those who implicitly or explicitly uphold and reinforce systems that trap certain communities in generational poverty.

Outside investment, perfectly exemplified by SpaceX, has long had a heavy hand in Brownsville’s history. Non-local corporations, land speculators, and investors have developed major projects that have greatly influenced the economy and daily life. Yet the profits from these endeavors generally do not stay in Brownsville or make their way to the bank accounts of those working in the region.

It is useful to trace these patterns of inequality, instability, and extraction through the region’s history, starting with the colonization and subjugation of the native communities (Estok’ Gna, Alazapas, Coahuiltecan, Rayados, and Lipan Apache)2“NativeLand.ca.” Native Land. Native Land Digital. Accessed December 15, 2020. by the Spanish with the 1747 founding of the Nuevo Santander Colony. In his book With His Pistol in His Hand, Brownsville-born writer and folklorist Americo Parades writes, “the colony of Nuevo Santander was settled much like the lands occupied by westward pushing American pioneers, by men and their families who came overland, with household goods and their herds.”3Paredes, A., Calderon, H., & Lopez-Morin, J.R. (2000). Interview with Americo Paredes. Nepantla: Views from South 1(1), 197-228. See source. The Spanish, in an effort to deter French expansion from Louisiana, enticed members of established colonies to the area with free land and government concessions, including “the freedom from interference by officialdom in the faraway centers of population.”4Paredes, Américo, 1915-1999. “With His Pistol in His Hand,” a Border Ballad and Its Hero. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1975. Pg 8.

Settlements were established along the banks of the Rio Grande, and by 1755 the towns of Laredo, Guerrero, Mier, Camargo, and Reynosa were burgeoning centers of a cattle economy.5Alonzo, Armando C. Essay. In Tejano Legacy: Rancheros and Settlers in South Texas, 1734-1900, 55. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 1998. It was the growth in ranching that led a group of entrepreneurial families from Reynosa and Camargo to set up cattle-raising sites along the mouth of the river in 1774 in what is now Matamoros.6Gobierno Del Estado De Tamaulipas, 2020. See source.

In 1781, the Spanish government granted Jose Salvador de la Garza, the captain and chief justice of Camargo, more than 260,000 acres of land north of the river—including all of what is today Brownsville.7Garza Falcón, María Gertrudis de la (1734–1789) Clotilde P. García. See source. The grant was known as the Espíritu Santo (Holy Ghost) grant. Salvador de la Garza, like many, went into the cattle industry and helped Matamoros become the metropolis of the colony, surrounded by self-sustaining ranches and tight-knit villages hidden in the heavy thornscrub forest of mesquite trees.8Paredes, Américo, 1915-1999. “With His Pistol in His Hand,” a Border Ballad and Its Hero. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1975. Pg 9.

Mexico’s fight for independence from Spain between 1810 to 1821 was followed by the westward expansion of Anglo-Americans such as Stephen F. Austin, known as the father of Texas. Many of these Anglo-Americans were driven by the concept of Manifest Destiny and held ingrained white supremacist and capitalistic ideas about race and class that rendered local Natives, Blacks, and Mexicans as inferior others. The animus of Anglos towards other groups in the region led to increased violence, low-balling of land, and cattle theft by “cowboys” and entrepreneurs.

Racial tensions bubbled as the Texas Revolution and the subsequent establishment of the Republic of Texas in 1836 turned the Rio Grande region into disputed territory, claimed by both Mexican authorities and the newly independent republic. By this time, herders and farmers from Matamoros had settled on the other side of the river: a community that evolved into Brownsville.9Garza, Alicia A, and Christopher Long. “Brownsville, TX.” TSHA. Texas State Historical Association. Accessed December 14, 2020.

Because of the distance from major populations, the regional identity that formed along the river was distinct from that of other Mexican, American, and Texan regions. In 1840 an insurgency against the Mexican government by the political elite of the northern Mexican states of Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, and Tamaulipas, along with Laredoans and Rio Grande residents like Antonio Zapata, led to the establishment of La Republica del Rio Grande.10David M. Vigness, “Republic of the Rio Grande,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed November 29, 2020, Published by the Texas State Historical Association. See source. Although it lasted only 283 days before succumbing to the Mexican military, the Republic of the Rio Grande showed the spirit of self-determination that Tejanos,11“Historians have applied the term specifically, perhaps anachronistically, to those Mexican Texans in Spanish Texas, to distinguish them from residents of other regions, and in Texas from the end of the Spanish era in 1821 to Texas Independence in 1836, in contradistinction to the Texian or Anglo-American residents of that time and of the Republic of Texas. Increasingly, Tejano, as a term denoting regional identity, referred to Mexican Texans of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and to the Hispanic Texans of the Spanish era.” See source. Mexicans, and Natives in the region continue to possess, defining a structure of governance to meet their interests and needs.

The Lower Rio Grande became a battleground once again after the United States annexed the Republic of Texas in 1845. Newly elected President James K. Polk sought to pressure the Mexican government into agreeing to the Rio Grande as the international boundary of the disputed territory.12“Biographies: John Slidell: A Continent Divided: The U.S.-Mexico War.” Biographies: John Slidell | A Continent Divided: The U.S.-Mexico War. University of Texas at Arlington. Accessed December 14, 2020. See source. After Mexican authorities refused to meet with an American diplomat in January 1846, Polk ordered US soldiers stationed in Corpus Christi to set up Fort Texas on the river across from Matamoros, a Mexican stronghold. As a response to what they considered an act of war by the United States, the Mexican Army crossed the river on April 24 and were met by a party of US cavalry led by Captain Seth Thornton.13“Rancho De Carricitos.” National Park Service, June 15, 2018. See source. The skirmish ended in the capture and death of American troops. The shedding of American blood gave Polk a reason to request that Congress declare war against Mexico.

Meanwhile, Mexican forces continued to push into the disputed territory. A siege on Fort Texas by the Mexican army began on May 3 and continued as Mexican and American forces (the latter under the command of future president Zachary Taylor) met nearby at the Battle of Palo Alto on May 8, 1846, and the Battle of Resaca de Las Palmas the following day. These marked the first battles of the Mexican-American War.

Following American victories at Palo Alto and Resaca de Las Palmas, the siege on Fort Texas ended as the Mexican army retreated across the river to Matamoros. Major Jacob Brown was one of two casualties from the siege, which Taylor renamed Fort Brown in his honor.

Remnants of Fort Brown on an abandoned golf course located behind the border wall. Credit: Jesse Miller

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war in 1848 and, as Americo Paredes describes, “added the final element to the Rio Grande society, a border. The river, which had been a focal point, became a dividing line. Men were expected to consider their relatives and closest neighbors just across the river as foreigners in a foreign land.”14Paredes, Américo, 1915-1999. “With His Pistol in His Hand,” a Border Ballad and Its Hero. Austin : University of Texas Press, 1975. Pg 15.

Taking advantage of the Mexican defeat and the new location of the international boundary, Charles Stillman, a merchant and industrialist from Connecticut, purchased—with the aid of racist legal rulings of dubious merit—a large amount of the Espíritu Santo grant north and northwest of Matamoros from the squabbling descendants of Jose Salvador de la Garza for a fraction of its worth. Stillman had amassed considerable wealth through mining in Northern Mexico, textile production, and transportation (including of American troops during the Mexican-American War).15Hart, John Mason. “Stillman, Charles (1810-1875)”, Handbook of Texas Online Date Accessed: December 14, 2020. See source. Published by the Texas State Historical Association. Stillman and partners established the Brownsville Town Company, named after Fort Brown, and renamed the area Brownsville. In 1849, Brownsville was made the county seat; it outgrew Matamoros as a trade port soon after.16Garza, Alicia A, and Christopher Long. “Brownsville, TX.” TSHA. Texas State Historical Association. Accessed December 14, 2020. See source.

State-sanctioned violence by the Texas Rangers, as they consolidated Texan and American Anglo rule, against Mexicans, Tejanos, and Natives,17To white settlers Tejanos, Mexicans, Natives and Blacks were all “other” and “less than.” along with land grabs by men like Charles Stillman against Mexicans along the border, enforced and normalized discrimination and brutality.18Paredes, Américo, 1915-1999. “With His Pistol in His Hand,” a Border Ballad and Its Hero. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1975. Pg 18. While some in the area actively protested this brutality, it persisted nonetheless. For example, a decade after the city’s establishment, Juan Cortina, a descendant of Garza, witnessed an Anglo marshall beating Cortina’s former employee, a Tejano, and shot the marshal. This was the beginning of Cortina’s War, an armed uprising during which Cortina led a group of armed forces who released imprisoned Mexicans and Tejanos who had been unfairly jailed, in addition to executing Anglos who had murdered Mexicans. The uprising lasted six months, and although he was eventually defeated by Texas Rangers and US Troops, Cortina became a legend, and the Rangers continued their campaign of violence for generations.19Learn more about the Texas Rangers’ history of violence.20“Juan Cortina”, PBS, New Perspectives on the West. Accessed November 28th, 2020. See source.

The city of Brownsville as we know it today was born from these repeated waves of Spanish, Mexican, Texan, and American colonization for economic gains. In the book Place Identity Formation in the Lower Rio Grande Valley: The Identity of Brownsville, Texas, author Elim Zavala argues that “the historical cycles of the [Lower Rio Grande Valley] and Brownsville suggest that both military and economic factors played a strong role in the identity construction of the region.”21Zavala, Elim. “Place Identity Formation in the Lower Rio Grande Valley: The Identity of Brownsville, Texas .” New Studies in Rio Grande Valley History, vol. 16, 2018, pp. 5–33. Other than the river, most of what defines the regional economy and the city’s identity today—the military-industrial complex, agribusiness, international trade, maquiladoras (foreign-run factories just across the border)—are examples of such outside entities, now most often corporations. Since the township’s inception, these ventures, while beneficial for the economic growth of the city, have primarily benefited those in power and outsiders at the expense of local and non-Anglo communities.

These ongoing systemically oppressive patterns of development have contributed greatly to the challenges that the city faces. The Texas–Mexico border represents one of the four regions of persistent poverty22Regarding persistent poverty as defined by the USDA “An important dimension of poverty is its persistence over time. An area that has a high level of poverty this year, but not next year, is likely better off than an area that has a high level of poverty in both years. To shed light on this aspect of poverty, ERS has defined counties as being persistently poor if 20 percent or more of their populations were living in poverty based on the 1980, 1990, and 2000 decennial censuses and 2007-11 ACS 5-year estimates.” “Rural Poverty & Well-Being” USDA. Accessed March 28th, 2021. See source. in the US. Brownsville is often ranked among the poorest cities in the country.23Hlavaty, Craig. “Brownsville named the poorest city in America.” Houston Chronicle. October 30th, 2013. See source.; “America’s Poorest Cities”. USA Today. September 28th, 2018. See source. Residents have the lowest average credit scores in the nation, and many lack education. Most jobs pay low wages, and generational poverty is deeply entrenched, making the purchase of a home and accumulation of wealth extraordinarily difficult. The community experiences exceptional levels of chronic physical illness, high rates of obesity, and a widespread lack of insurance. Residents of Brownsville’s surrounding colonias—unincorporated areas characterized by a lack of adequate infrastructure and/or housing—have been excluded from improvements in the built environment. Despite the need for more connectivity between Brownsville and nearby colonias, highway projects, which prioritize the needs of car owners, are approved over investment in public transportation, connection to parks, or other opportunities that could better meet the basic needs of the area’s lowest-income earners.

And yet, these patterns of development persist: most evidently in the continued investment in the militarization of the border,24Federal spending in border enforcement has between 1986 and 2019 total $263 billion. During the Trump administration, $16.3 billion was spent on border wall construction. See source 1; See source 2. burgeoning natural gas production, and the growth of the private space and tech industries. It is significant that the region’s most visible infrastructure project is the border wall. Brownsville’s political elite continues to enforce economic development that allows extractive outside capitalists and market forces to define the city’s identity. To welcome a new wave of capitalist development via SpaceX, the city recently declared that it would be known as New Space City by 2030. This mirrors the “Magic Valley” slogan used by transplant midwesterners in the early part of the twentieth century to lure other midwesterners to grow the agricultural sector, halting traditional ways of ranching and converting the area to large-scale commercial farming operations still dominated by Anglos.25Naveena Sadasivam, “The Making of the ‘Magic Valley’,” The Texas Observer, August 2, 2019. See source. Both slogans hide the conditions and experiences residents face.

The US Census Bureau reports that 86 percent of households in Brownsville do not speak English at home, yet city business is conducted and printed primarily in English. Public meetings and stakeholder sessions are advertised and conducted in a way that leads to primarily English-speaking residents attending. This sends strong signals about whose input is more valid and wanted. Brownsville is beginning to recognize this and has taken steps to change, but more is needed.

One structural barrier to having truly representative government in the city is that the mayor and city commissioners are unpaid. These positions require significant time commitments, generally meaning that only wealthy individuals or business owners can afford to hold them. Decades of this rule-by-elites structure has led to apathy. Most residents do not vote, likely because they do not see themselves represented in the candidates up for election, and because they’ve witnessed a city that continues to serve a wealthy minority while failing to meet the needs of the majority. Recently, the city commission voted to place term limits on an upcoming citywide referendum. While Brownsville’s residents will have an opportunity to vote to place term limits on the mayor and commissioners, there are bigger steps to be taken to create a more representative leadership structure. Providing fair compensation for these positions would be an important step.

This report is meant to bring to light the harms of the status quo and the damage caused by decisions that implicitly and explicitly disadvantage those facing the greatest challenges. The report aims to recenter the narrative about Brownsville away from an oversimplified focus on immigration and border walls and instead toward the complex, interrelated, and systemic challenges facing the city—away from those maintaining this status quo to those fighting to dismantle white supremacy and injustice. The following features reveal not only the daunting challenges that Brownsville faces, but the incredible and beautiful work that is being done daily to address them. It is time to uplift the voices of those who are working to make the city a more equitable place, to celebrate their voices and their labor.

We, the editors of this report, got to know each other, as well as many of the contributors, through our work in affordable housing. Jesse and Lizzie both came to Texas (Brownsville and Dallas, respectively) to work at buildingcommunityWORKSHOP ([bc]), a nonprofit community design center that has an office in Brownsville, which Jesse led for a number of years. Through working on affordable housing and creative placemaking in the Rio Grande Valley, we met Josué while he was with Texas Housers, an affordable housing advocacy nonprofit. Josué now works with come dream. come build. (cdcb), a nonprofit community development corporation in Brownsville. Prior to joining [bc]’s Dallas office, Kelsey, who is from a small town in north Texas, was an intern with cdcb, living in Brownsville.

Editing this piece is a privilege. We come to this project accustomed to having our voices heard. We come from education, from connections with those in power and influence, and with means to be able to dedicate time and energy to a project like this. This is not normal for most of Brownsville’s residents, or for most people around the country. We felt it important to work with contributors whose perspectives are missing from current media and storytelling about Brownsville.

Biographies

is director of urbanism at buildingcommunityWORKSHOP [bc], where she has worked on projects ranging from community engagement for the City of Dallas’ cultural plan to El Sonido del Agua, an arts and advocacy project in the Rio Grande Valley, and design guidelines for Main Street, Millinocket, Maine, as part of the Citizens’ Institute on Rural Design. Prior to joining [bc], she worked at OMA/AMO in Rotterdam, Netherlands, as an editor of Elements of Architecture by Rem Koolhaas. She received master’s degrees in urban design and art, design, and the public domain from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and a bachelor’s degree in architecture from Carnegie Mellon University. MacWillie is a member of the equity, diversity, and inclusion committee of the Texas Society of Architects and serves on the advisory board of Columns Magazine.

is the development manager at [bc]. She oversees the organization’s fundraising and development, cultivating valuable relationships with key stakeholders ranging from large organizations and communities to single individuals—all of whom have at least one thing in common: a commitment to building strong, sustainable, and equitable cities. She previously worked as a copywriter for a local nonprofit development agency before teaching English as a foreign language in Bogotá, Colombia. While completing her master’s degree in urban management, Menzel partnered with the Community Development Corporation of Brownsville to research affordable housing approaches in the colonias of Cameron County. She has a bachelor’s degree in English from The University of Texas at Austin and a master’s in urban management from the Technical University of Berlin, Germany.

(AIA) is an architect with Megamorphosis in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. He works “to create places and spaces where people can thrive by using a diverse set of skills and experience in award-winning architecture, community planning, and community education projects and initiatives.” Miller earned a master’s degree in architecture at Ball State University, located in his home state of Indiana. While in graduate school, he studied at the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey in Monterrey, Mexico, working on his thesis, “Between Tradition and Dissent: Learning From and Working With Ignored Communities.” Miller is an adjunct professor in the architecture program at Texas Southmost College in Brownsville, working with students on service learning projects with local municipalities and nonprofits. He serves as vice chairperson for the Housing Authority of the City of Brownsville and treasurer of the AIA Lower Rio Grande Valley executive committee, and is a member of the Texas Architect Magazine publication committee.

is the Mi Casita program coordinator at come dream. come build. in Brownsville, Texas, where he has served since 2019. Ramirez guides participating families in the colonias and rural communities of Cameron, Hidalgo, and Willacy counties through the homeownership process. He graduated from the University of Texas at Austin with a degree in Mexican American Studies with a focus on public policy. He is a multidisciplinary artist working through visual art, installation, crafts, and performance. His artwork has been exhibited in the MexicArte Museum, Art League Houston, the Brownsville Museum of Fine Arts, as well in publications like Remezcla and Pitchfork. Ramirez serves as the Director of Raw Creativity for Trucha RGV, a media collective and online platform focused on the region’s arts, culture, and social movements. He is a founding member and is responsible for creative/cultural programming.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.