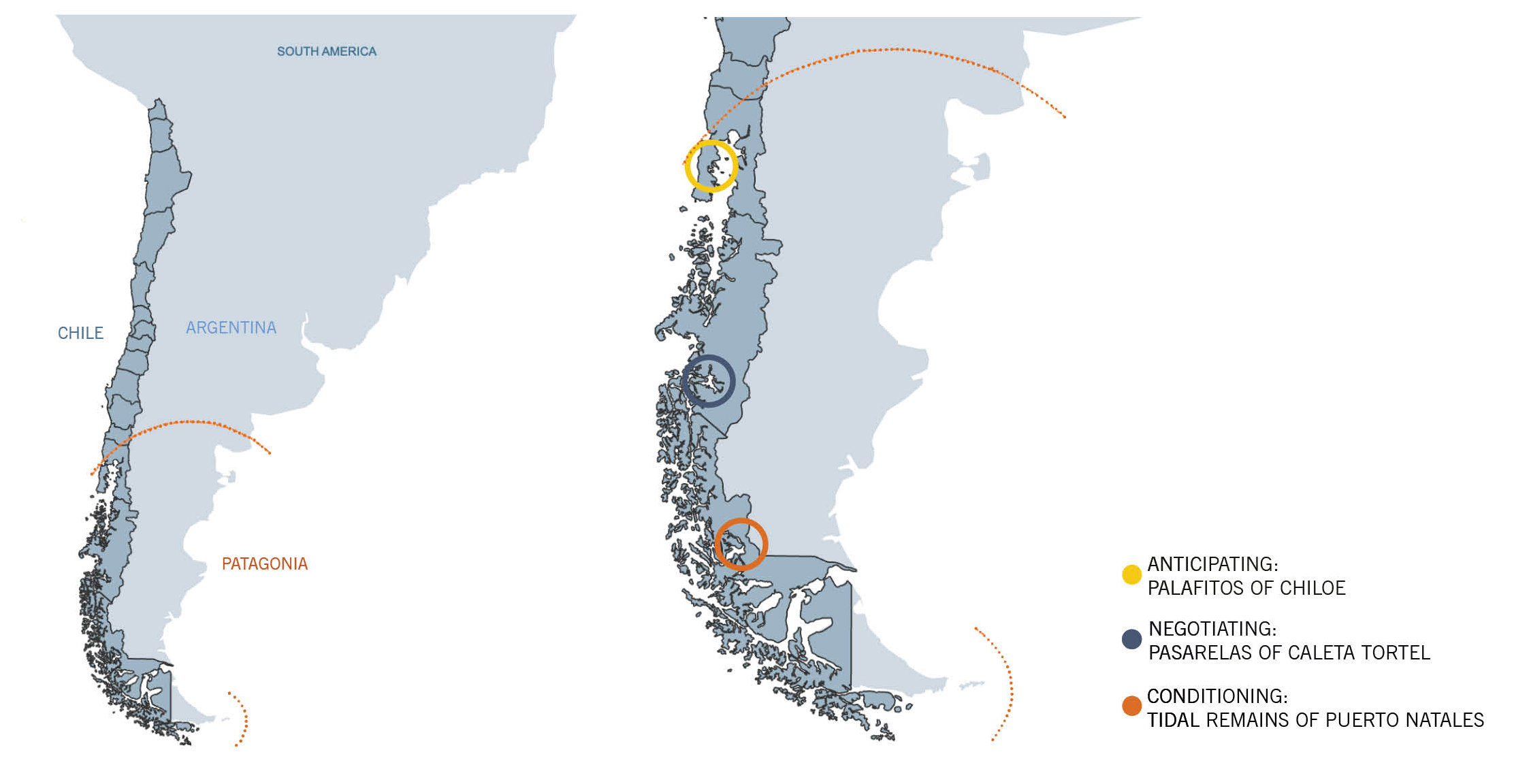

Anticipating, negotiating, conditioning: Tidal infrastructures of Patagonia

Melanie Kaba travels to "the end of the world" to investigate structures in Patagonia’s harsh coastal environments.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Melanie Kaba received a 2011 award.

In anticipation of change

According to the scientific community, global climate change is accelerating and sea level is on the rise due to higher temperatures and glacial melting. The effect of these changes on coastal infrastructure and communities is overwhelmingly negative, as sea level rise leads to severe flooding, evident in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Additionally, rises in ocean surface temperatures lead to a greater frequency of storm surges and tsunamis, such as the recent devastating events in Japan and Thailand. The relevance of this subject to the architectural profession has become more pressing in recent years as we learn about the effects of climate change on the built environment, in particular where it interfaces with the rising tides of the sea.

Certainly, projective design research is imperative; competitions and visionary architectural projects produce a new architectural conversation. This allows the discipline to question how to mitigate these changing territories and consider new ways to design with responsive flexibility in mind. But alongside this projective ideation, it is valuable to document how this issue is being dealt with on a local scale in already-existing extreme terrains. There is still a lot of work to be done in the field, as there are many existing examples of vernacular responses to tidal conditions from which to mine and extract information.

A natural reaction: “Soft infrastructures”

Often vernacular architecture gets marginalized as simplistic, obvious responses to design. And as Anthony Reid notes, “It may be that the notion of tradition leaves people feeling uneasy, with associations to a world of convention and constraint; they feel that traditions belong to a place in the past…” But if one researches how current and traditional vernacular building systems develop to adapt to specific climate conditions, a rich design resource gets reclaimed and brought back into contemporary practice. Certainly, learning from the masters of design is important. However, as Paul Oliver tells us, over 80% of the built works on Earth are vernacular architecture, built by “the people.” Researching vernacular bioclimactic architecture gives us a fundamental understanding of how built form can respond to extreme environments.

Studying vernacular typologies is important not only from a materials standpoint, but also in terms of understanding how they were built to respond to different scales of economy. They engage with site not only at the scale of shelter, but also at the level of community and neighborhood infrastructure. As a community, their formal response to climactic conditions then impacts and changes the landscape they inhabit. Often they become an ecology of their own—a built ecology that reciprocates with the natural one in which it resides. This vernacular response is what Guy Nordenson calls “soft infrastructures.” They are reflexive and responsive to the situation, allowing for more change or growth within the system. Frequently, vernacular architectures allow for weatherization processes to take part in the design of the form. Just as wind takes on the role of co-architect in the Scottish black house, snow in the Japanese minka house, and sun/water combination in the Indian stepwell, this allowance for partial “un-authorship” creates part of the flexibility in the system in terms of adaptation and anticipation. The architecture becomes participatory, not purely reactionary.

How does vernacular architecture participate and respond to tidal forces at the water’s edge? Where does one find an “extreme” location to research these conditions?

Dwelling at "the end of the world"

In June 2012, the Norden Fund allowed me the unique opportunity to study these concepts at three points along the windswept Chilean coastal region of Patagonia. Chile itself is a proportionally unusual territory. Both thin and long, it is only 110 miles east to west, but stretches 2,600 miles from north to south. The elongated Chilean coast touches the Pacific Ocean, the Atlantic Ocean, and also Cape Horn, the southernmost point in the Americas.

As a territory, Patagonia is rife with extremes, a “battleground for the (natural) elements.” Its precise boundaries aren’t clear. Often referred to as “the end of the world,” it occupies the southern parts of both Chile and Argentina and contains highly variegated, extreme landscapes. At times stark, with its seemingly endless fjords, glaciers, and pampas grasslands, it is simultaneously rich with its variety of ecosystems. Its notoriously severe winds that originate in the Andes are referred to as “the broom of God,” and the harsh coastal waters are something Patagonians have been handling since the beginning. The intensities that nature serves here are vast and uncompromising.

How does one mitigate all these factors to inhabit land and create space along this intense coastline? How does the connection between land and water produce a vernacular architectonic response here? Chilean Patagonia’s rugged terrain threads with the Pacific Ocean to produce a variety of unique inhabited environments. I visited three differentiated and anomalous sites along this coast, from the most northern boundary to the southernmost part of Chilean Patagonia, observing a different scale at each location to see how people have responded to tidal forces at play and to understand how these interventions create their own infrastructures.

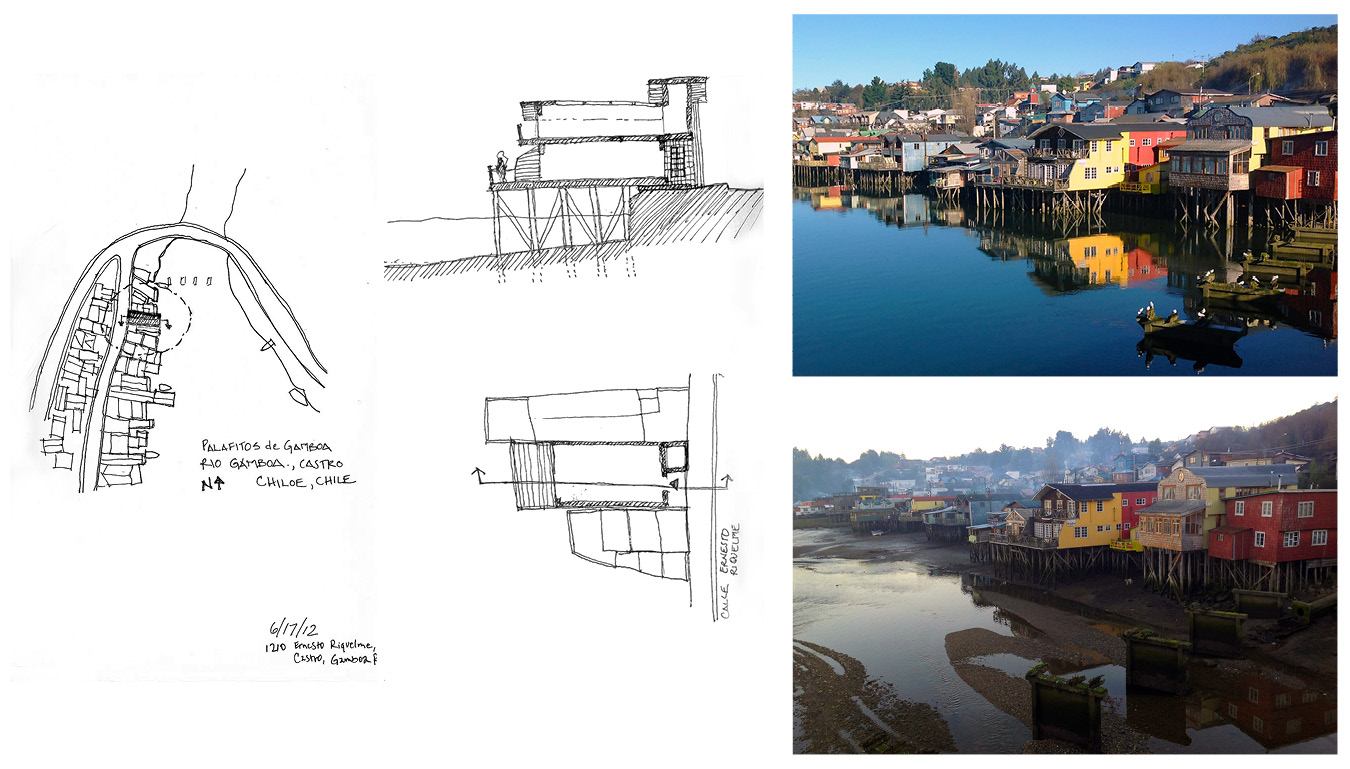

Anticipating: Palafitos de Chiloe

Chiloe is Chile’s largest island. At 111 miles long and 31 miles wide, it sits between the gulfs of Corcovado and Ancud in the Los Lagos region, just at the northernmost tip of Patagonia. The city of Castro is the capital of Chiloe and contains the country’s most concentrated population of palafitos, or vernacular stilt houses. Built along the shoreline, these structures intertwine sea with land. Built upon columns embedded in the floor of the bay, these wooden structures anticipate the shifting landscape of 6-hour tides. The most notable palafitos in Castro are in the fishing neighborhoods of Gamboa and Pedro Montt.

Because the stilt houses are situated both on an urban street and a maritime “backyard,” they have dual facades and take on different functions at both faces. The concept is that one can return home from fishing by boat through the back door and then leave home through the front door, at street level. The palafitos anticipate the tides, allowing the water to move underneath and fundamentally change the atmosphere of the home. The piers the houses sit upon are embedded deep in the ocean floor; this support structure is visible only at low tide. At high tide, from the back facade, the houses appear as though they are floating above the water like boats. The form provides shelter from humidity due to the double height of the stilts.

Because Chilotan stilt houses are found in informal flocks, not as singular entities, they depend on one another for infrastructure and structural support.

Palafitos were historically wooden single-story structures built by the owner. Today, however, the palafitos of Castro can be many stories and are all on public land, and therefore homeowners can’t hold title deeds.

Palafitos can be moved, and the act of moving a home on Chiloe is a community event known as a minga. If a household needs to move due to weather or tides, the neighbors all work collectively to make the move of the structure a ceremonial event. The use of tidal forces facilitates the choreography of the move, and buoys attached to the underside of the structure facilitate the moving process.

Castro has seen its share of natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods, and fires. These wooden palafitos have survived natural disasters and are some of the last remaining structures of their breed in the country. They are in political turmoil, as the local government has deemed them unsanitary and is contemplating tearing them down to make way for more “modern” structures. However, the palafitos have engendered a strong cultural (as well as formal) identity within this community, and the stilted neighborhoods will most likely remain a Chilotan vernacular for many years to come.

Top: Informally emergent vernacular: Los palafitos de Pedro Montt, Castro. Bottom: Map of Caleta Tortel, Tortel, Aysen Region, Chile. Credit: Melanie Kaba

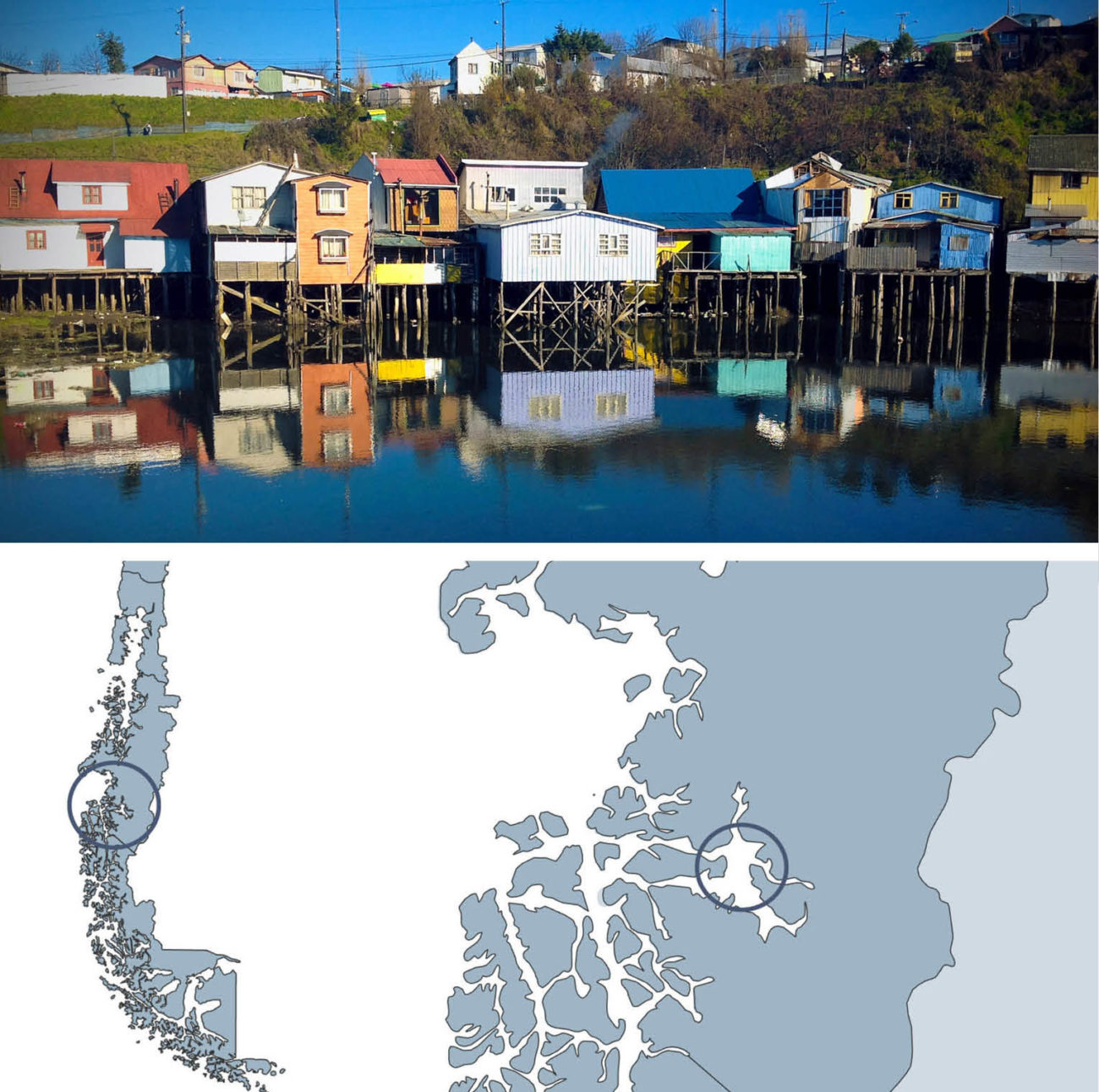

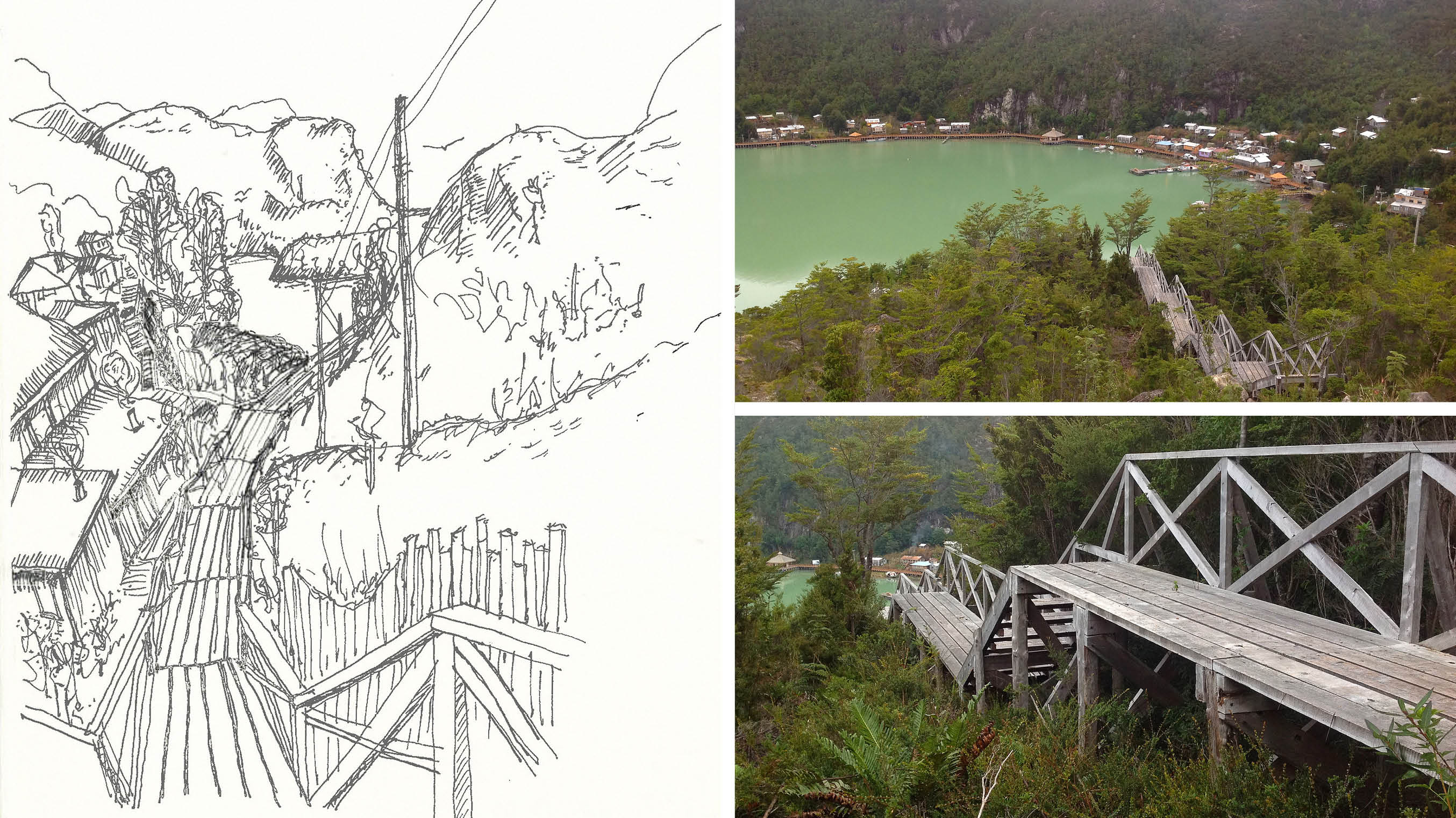

Negotiating: Pasarelas de Caleta Tortel

Further to the south, in the remote Aysen region of Patagonia, lies a fantastical wooden pedestrian infrastructure. Caleta Tortel is a village located between ice fields at the mouth of the Baker River delta, an estuary composed of ice fields, fjords, and a web of channels. This area became inhabited in 1955, not as a fishing village, as would be typical, but rather due to lumber harvesting of the immense cypress forests in nearby Guaitecas. It was only accessible by boat and plane, making it difficult for anyone who wasn’t directly involved in the lumber economy to stumble upon. The road that now reaches this nearly mythic city, the Carretera Austral, was built in 2003. It is not fully paved, and because of weather it is often difficult to traverse. Caleta Tortel is still a workout to reach, and one would not accidentally arrive here.

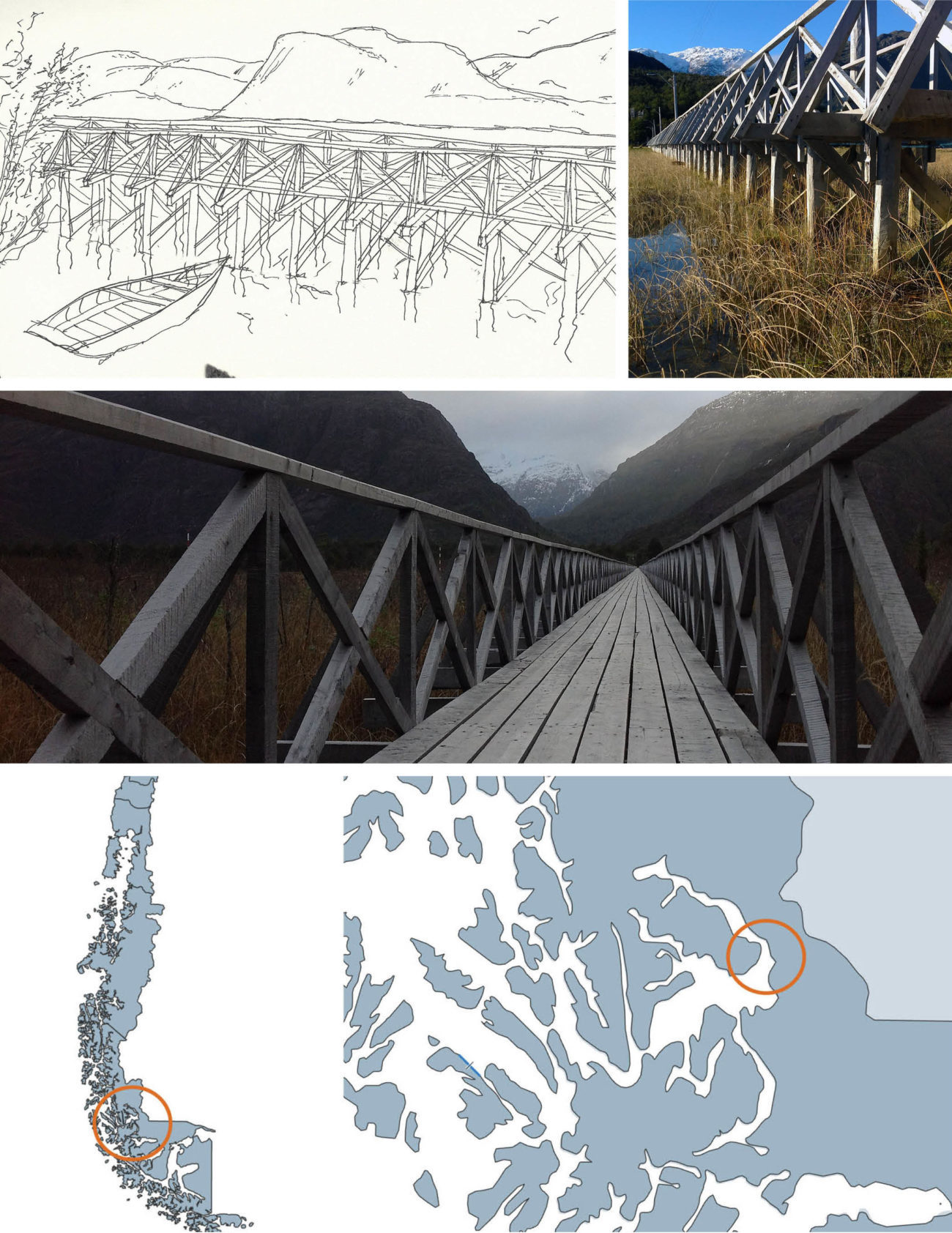

Left: Descending into Caleta Tortel, sketch. Right: Tortel Cove and pasarela construction. Credit: Melanie Kaba

Also a challenge to inhabit, Tortel is home to only 525 inhabitants. Here the palafitos are all connected by a complex web of wooden pasarelas (footpaths) and bridges that are the only connective tissue, as there are no conventional sidewalks or roads due to the tides and the rocky terrain that one must negotiate here. This car-free network of walkways, bridges, and stairs connects the stilt homes to the piers, and one can only enter the settlement through bridged gateways that serve as the town’s thresholds. This complex network weaves together an intrepid pedestrian and landscape-lover’s paradise.

Top left: Ascending Caleta Tortel. Top right: Elevational intersection sketch. Bottom: Pasarelas, a vernacular connection of land and sea. Credit: Melanie Kaba

The wooden buildings here are simultaneously sewn into the landscape, to the other buildings, and into the community by these threads of footbridges. Traversing these is not just a horizontal activity, but sectional as well, as some of the stairwells are steep and seemingly never ending. This gives the town an appearance of wooden structures being piled atop one another and strung precariously together by a maze of connective boardwalks situated in the mouth of an estuary that forms around a cove. The cove waters are a milky aquamarine, having been fed by glacier water for thousands of years.

The pasarelas and buildings are built using the Guaitecas Cypress that is harvested in the region. There are many parts of the pasarelas that are in state of rebuild. This constant reconstruction gives the town a temporal sense; this adds an element of ephemerality to the wooden Patagonian vernacular.

Top left: Wooden Guaitecas cypress construction sketch. Top right: Guaitecas photo. Middle: Pasarela crossing through valley. Bottom: Puerto Natales, Natales, Magallanes and Antartica Chilena Region, Chile. Credit: Melanie Kaba

Conditioning: Corredor alargado de Puerto Natales

Situated at the southernmost part of Patagonia is the quaint town of Puerto Natales. This idyllic harbor city, which sits on the shores of Seno Última Esperanza (Last Hope Sound), has taken on many roles through the years as a connection hub. As a passenger port of call for the main tourist water transportation systems, the “beginning of the end” marks the way for people heading further south into the Strait of Magellan and down to the southernmost points of Tierra del Fuego. Today, Puerto Natales marks the primary entry point to Torres del Paine, arguably Chile’s most iconic national park. Because of this, it is a busy hub for international tourism, and unlike the previous two locations it has a large influx of daily visitors. This modernized destination has many contemporary structures that make a strong reference to the Chilean vernacular of stilt homes and farmhouses through the use of form and materiality.

Along the Última Esperanza Sound, everything is viewed as if through an elongated corridor, or corredor alargo. The decaying docks, the history, the sunsets, the fjords, and the inlet’s glacial destination are all seemingly endless and immeasurable. Here the many remains of historic piers and remnants of decayed infrastructure tell another vernacular story, one that Bruno Munari illustrates in his book, Sea as Craftsman.

Field studies

This three-part study of humble coastal environs at “the end of the world” has provided a platform to frame vernacular architecture. Visiting these acute natural conditions of the formidable Patagonian landscape and examining these vernacular architectural interventions gives insight on how to negotiate and interact with extreme terrains. In order to develop flexible, “soft” infrastructures and built systems that reciprocate with surrounding ecologies and anticipate the inevitability of change, we will need to continue studying severe situations as they become more commonplace. While continually documenting similar evidence that shows us how humans have successfully woven built conditions into extreme terrains (natural, political, or otherwise), we can begin to curate successful methods that people have developed for connecting form to systemic natural processes. Perhaps this can then inform architectural solutions that respond to rising tides and extreme weather conditions resulting from climate change.

Nordenson writes, “Interconnected infrastructures and landscapes rethink the current thresholds of water, land, and city.” These Patagonian field studies have led me to further this research—a lifelong field study I am engaged in as an architect and educator, continually examining the thresholds where land and water intertwine.

Biographies

is an architect and educator. She has taught in the architecture departments of the University of California, Berkeley; California College of the Arts; and the University of Michigan. Originally from Kansas, Melanie earned her BS in design and environmental analysis from Cornell University and her MArch from the University of Michigan. She currently practices architecture in San Francisco and is engaged in several projects where land meets the sea.

Explore

Arverne rebuilds: Water’s Edge, Arverne-by-the-Sea, and Arverne View

Emily Nathan covers the recent history of Arverne's development and its impact on those who call it home.

Case Study: The Great Lakes

The Great Lakes session of The Five Thousand Pound Life: Water brought together five experts to discuss and debate the problems and solutions facing North America’s primary source of fresh water.

The Plecnik projects: Public experience and the section of water

Kerry O’Connor writes about infrastructural public works by architect Jože Plečnik along two rivers in Ljubljana, Slovenia.