Agent Orange in A Luoi Valley

Ylan Vo visits A Luoi Valley to understand the long-term impacts of the United States Army's use of Agent Orange in the region during the Vietnam War.

February 26, 2015

Former A So U.S. Special Forces base overgrown by an abandoned timber plantation. Credit: Ylan Vo

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Ylan Vo received a 2015 award.

A Luoi Valley

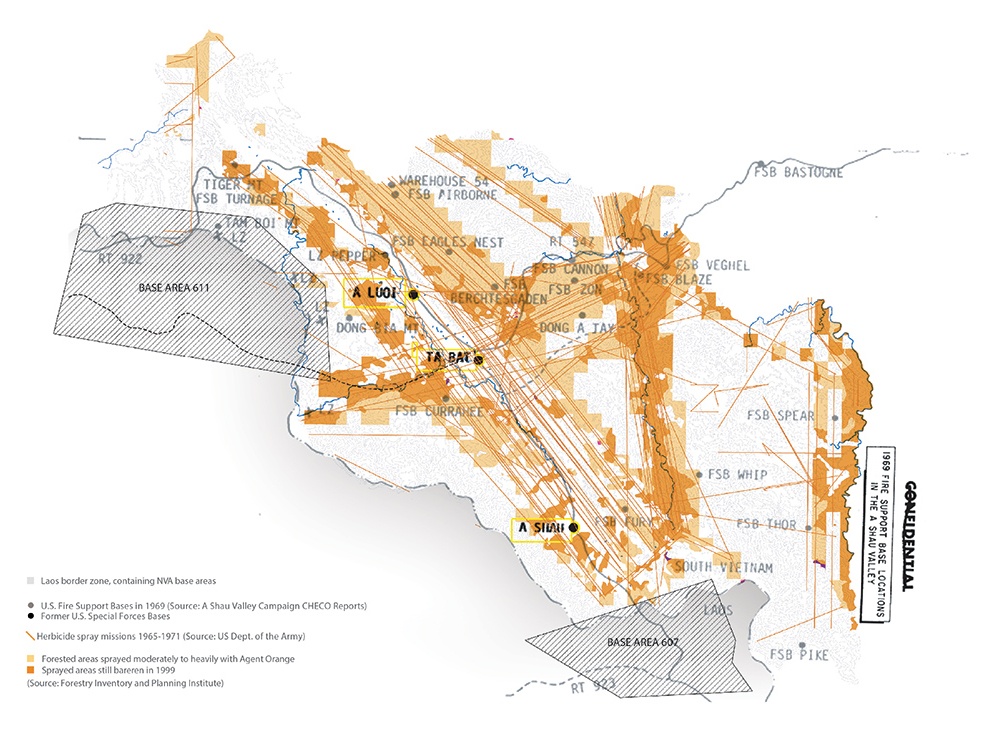

A Luoi is a rural district that was the site of intense conflict during the Vietnam War. Through the two-dimensional abstraction of military planning, the valley’s location not far south from the 17th Parallel (DMZ), just west of the imperial capital of Hue, and right at the VN-Laos border resulted in its strategic role at the center of multiple intersecting forces. A Luoi was part of a critical supply network along the Ho Chi Minh Trail used by the North Vietnamese Army to gain the advantage of interior lines with more efficient access to South Vietnam. The US established outposts and three Special Forces bases, but were forced to evacuate in 1966 and resort to heavy bombing and the use tactical herbicides including Agent Orange to inhibit movement of their enemy under cover of the valley’s dense vegetation.

Since the end of the war, A Luoi valley has been studied as a place where the use and storage of Agent Orange has damaged local ecosystems and left unknown potential “hotpots” with toxic concentrations of the chemical dioxin. The purpose of my travel was to understand long-term impacts and the restoration efforts around the use of Agent Orange from the U.S. war in Vietnam. From asking first about one particular hotspot in A Luoi, I spent my time in Vietnam following the trail of much broader questions about ecological systems and their deep interconnection with social, political, and economic systems in the region. While Agent Orange played a prominent role in emergence of international environmental consciousness during the 20th century, A Luoi valley remains a fascinating place that reflects many of Vietnam’s ongoing post-war challenges at the scale of small rural community.

The stories that landscapes tell

I began my travels in Hanoi to meet the botanist Phung Tuu Boi, known for his work over the past four decades to reforest Vietnam’s war-torn landscapes and his international activism around the ecological impacts of Agent Orange. Retired from his government post, Boi continues to consult on development in the remote A Luoi valley and realized a green fence project there in 2007 to isolate one area with high dioxin concentrations from access by local residents and livestock. In Hanoi, we visited the Forest Inventory and Planning Institute, where Boi and his colleagues have engaged in research on forest biodiversity as well as the development of a small herbarium, museum, and botanical garden. Though the inventory of species in the garden had been carefully documented and mapped, it falls short of capturing the rich stories of a generation of scientists who brought those specimens back from their travels, and the stories of the bomb craters that now host the garden’s aquatic plant life. I was inspired by this small institution that had already made a “living museum” of its post-war experience, now hoping to do the same at a landscape scale in A Luoi.

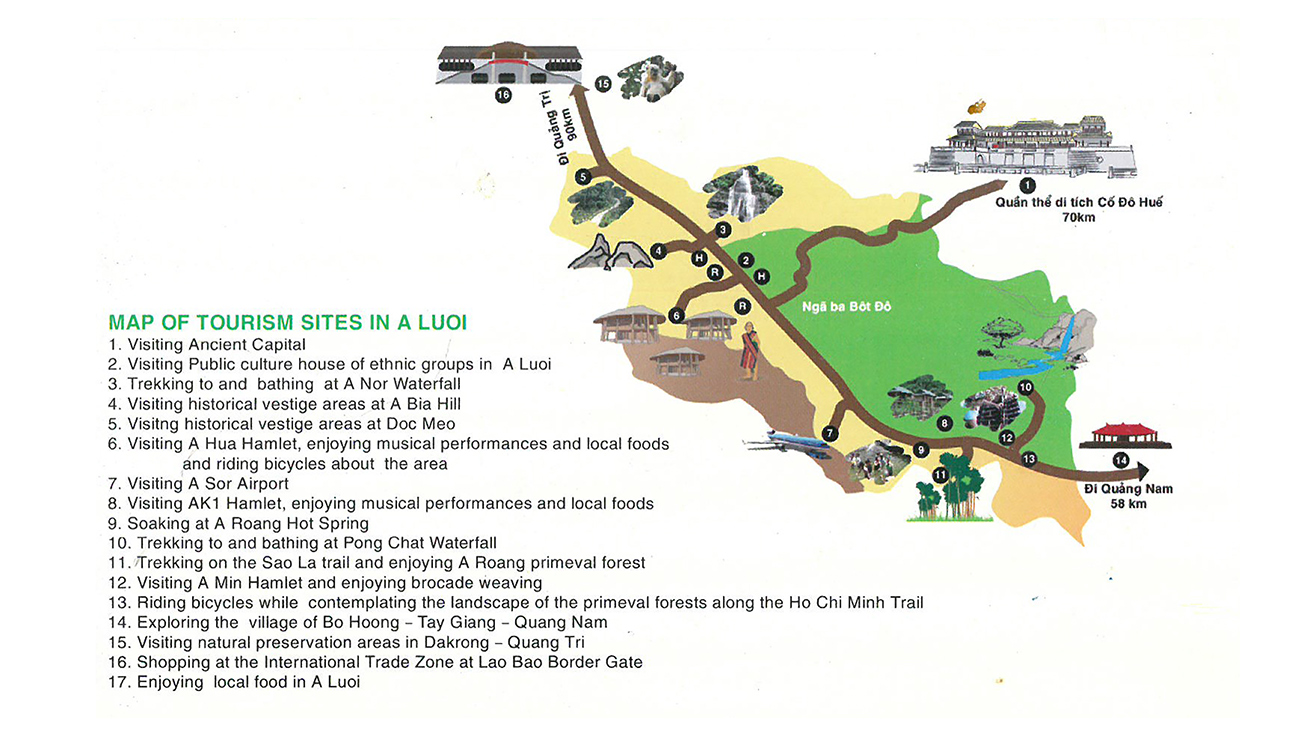

Boi helped me to develop an itinerary for traveling in A Luoi, which included the commune Dong Son, perhaps most affected by Agent Orange where the former U.S. Special Forces base A So still exists as ruins in an abandoned landscape. The other significant military site on my itinerary was A Bia Mountain, known to American veterans as “Hamburger Hill,” the site of a deadly 10-day battle in 1969 when the U.S. attempted to gain control of the valley. Apart from these historic sites, I also explored the region’s growing eco-tourism attractions including the A Nor waterfall, A Roang hot springs, trekking routes, and the Sao La conservation park (named for one of the world’s rarest large mammals that has yet to be spotted within the park). Experiencing this terrain by motorbike along newly built roads—today’s commercial and tourist routes—as well as by foot through dense vegetation, I was reminded of what anthropologist James Scott calls the friction of terrain or altitude. The U.S. military’s documentation and analysis from their terrain report makes clear how those landscape features considered least restrictive from a military/logistics standpoint became sites for airfield construction and later the areas most heavily targeted in bombing and spray missions. In the decades after the war, the same flat terrains that were navigated by vehicles and airplanes also attracted new residents who paved over the trails, repurposed cleared land for agriculture and bomb craters for aquaculture and irrigation.

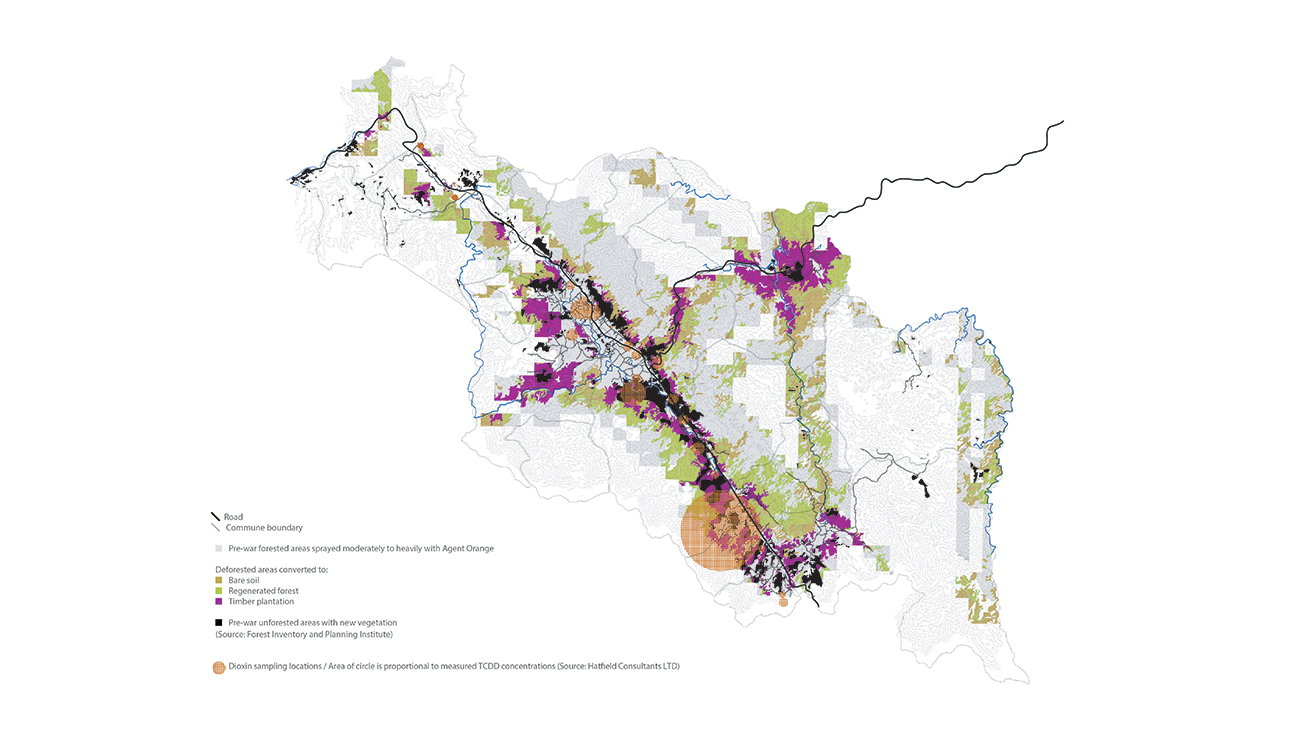

I had been told that recent years had seen a dramatic recovery of the tree canopy in A Luoi, and I arrived to find challenges quite different from the ones I was expecting. No longer an isolated “degraded” mountainside landscape, A Luoi today is green and newly electrified, with a growing town center, markets, guest houses, and even a popular karaoke joint. Along with new transplants from the coastal region, A Luoi’s indigenous ethnic minority populations have transitioned from shifting cultivation and the use of non-timber forest products to new permanent settlements on the valley floor, where they rely on wet rice cultivation and government services. Around half of productive land in A Luoi is owned by forestry companies, so the green “recovery” that I was witnessing is in fact the conversion of forest land to a cash crop monoculture. This economic and political integration was made possible by the militarization of A Luoi’s rural landscape, ultimately bringing a modern standard of living and new markets to once-remote communities, but also threats to biodiversity, cultural diversity, and traditional livelihoods. While Dong Son’s dioxin hotpsot has been contained and remains uninhabited, the most urgent concern of local residents was the stigma that their businesses and products carried from the commune’s association with Agent Orange.

The story of Agent Orange

While I witnessed some of the indirect consequences of Agent Orange on the ground in A Luoi’s ecological landscape, I was also eager to understand at a high level how the “story” of Agent Orange has continued to impact its social and political landscape. I was fortunate to attend the 2016 International Scientific Seminar on Agent Orange/Dioxin and learned that it was at the international dioxin conference in 1986 that many foreign scientists first became interested in studying Agent Orange in Vietnam. While the Russians were studying mangrove forests in south Vietnam, a team of Canadian researchers identified A Luoi as a potential research site since steep topography concentrated the effects of sedimentation and there was no industry or modern agriculture in the remote region. This provided the ideal living laboratory, isolating and preserving the impacts of war even decades later. In addition to being an area with high spray concentration and remaining evidence of chemical warfare, the entire A Luoi district was selected in 2010 to be the first official “evidence landscape” for Agent Orange, following a number of criteria including impacts on people, the environment, and potential alignment with a regional development plan.

According to Boi, this plan is a significant step towards offering a place for the entire nation to encounter the legacy of Agent Orange and preserve important lessons for future generations in the same spirit as Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park, which draws over one million visitors annually. Framing a critical design challenge, he hopes that the district will go beyond memorializing victims to establishing living institutions dedicated to research, education, and economic development. The 2010 master plan consists of three integrated components. The first is a visitor center in the central town square that includes museum exhibitions and educational facilities. The second component, centered around A So airbase in the southern part of the valley, is an environmental research center that will monitor existing patterns of ecological recovery and test new planting techniques. The third component would be a medical unit dedicated to treatment and research on the devastating human consequences of Agent Orange.

Exhibition of evidence from the chemical warfare perpetrated by American forces at A So airbase. Credit: Ylan Vo.

The implementation of a visionary development plan for A Luoi faces enormous technical and political challenges, from the need to build a predictive scientific model for the distribution of dioxin throughout the district to problems with management and coordination among various government agencies. While the U.S. government committed $41 million to clean up Agent Orange at Danang International Airport and has plans for the other urban sites at Bien Hoa and Phu Cat, A Luoi is in a remote location of low priority for resources and development aid. All that exists today to tell the story of Agent Orange is a small repurposed building in Dong Son displaying an exhibition that was put together within 10 short days—just before my visit in 2016, in time for the 50th anniversary of the defeat of American forces in A So. Along with a collection of military artifacts found and donated by local residents, the exhibition includes haunting photographs and data about the health impacts of Agent Orange in the district.

Within my limited role and time as a researcher, I had the privilege of being among the few foreign tourists who have spent time in A Luoi Valley. While domestic tourism is growing in the region, I found that A Luoi in its transitional state reflects the challenges faced by rural communities as well as an opportunity to consider landscape design and planning within a low-resource and culturally sensitive approach. In A Luoi today, there are increasingly negative environmental impacts that come with the ubiquitous infrastructure development of hydropower, road construction, and gold mining, and yet the district also carries unique legacies of warfare and rich traditions of the indigenous highland peoples. Werner Heisenberg (whose uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics states that in observing the world, we inevitably disturb it) described the registration of nature by an observer as “a transition from the possible to the ‘actual’,” and therefore merely that which forces one of many possibilities into existence. What remains with me as a designer is the understanding of design as both preservation and change—I learned about the landscape as an imagined scale for the museum and the laboratory to work as synergistic programs within this rural district.

Natural waterfalls are attracting visitors to A Luoi and offer promise of growing eco-tourism development. Credit: Ylan Vo.

My deepest gratitude goes to Phung Tuu Boi and the many incredible people I met working on the difficult challenge of Agent Orange in Vietnam. They have been in the trenches for many decades, choosing pain in the face of forgetfulness, action despite uncertainty, hope over despair.

Biographies

is a designer and researcher focused on strategies that integrate social and economic development with sustainable natural systems management. She currently works as a landscape designer at BatesForum in St. Louis, and is continuing research in central Vietnam through Site and Space in Southeast Asia, a collaborative project funded primarily through the Getty Foundation’s Connecting Art Histories initiative. Ylan earned her Master of Architecture and Master of Landscape Architecture degrees from Washington University in St. Louis, and BA in History of Art and Architecture from Brown University.

Explore

Deserted border lands: Mapping surveillance along the Tohono O’odham Nation

Studying the impact of border surveillance and militarization at the US–Mexico border on O'odham landscape and culture.

Anna Heringer: Sustainability=Beauty

The German architect speaks about her love of mud as a building material.

Tillers of the horizon: Projecting public spaces by women in post-conflict Rwanda

Yutaka Sho explores how Rwandan communities are turning petrochemical waste into affordable and high-performance houses.