Deserted border lands: Mapping surveillance along the Tohono O’odham Nation

Caitlin Blanchfield and Nina Valerie Kolowratnik write about the impact of border surveillance and militarization on the O'odham landscape and culture.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Caitlin Blanchfield and Nina Valerie Kolowratnik received a 2016 award.

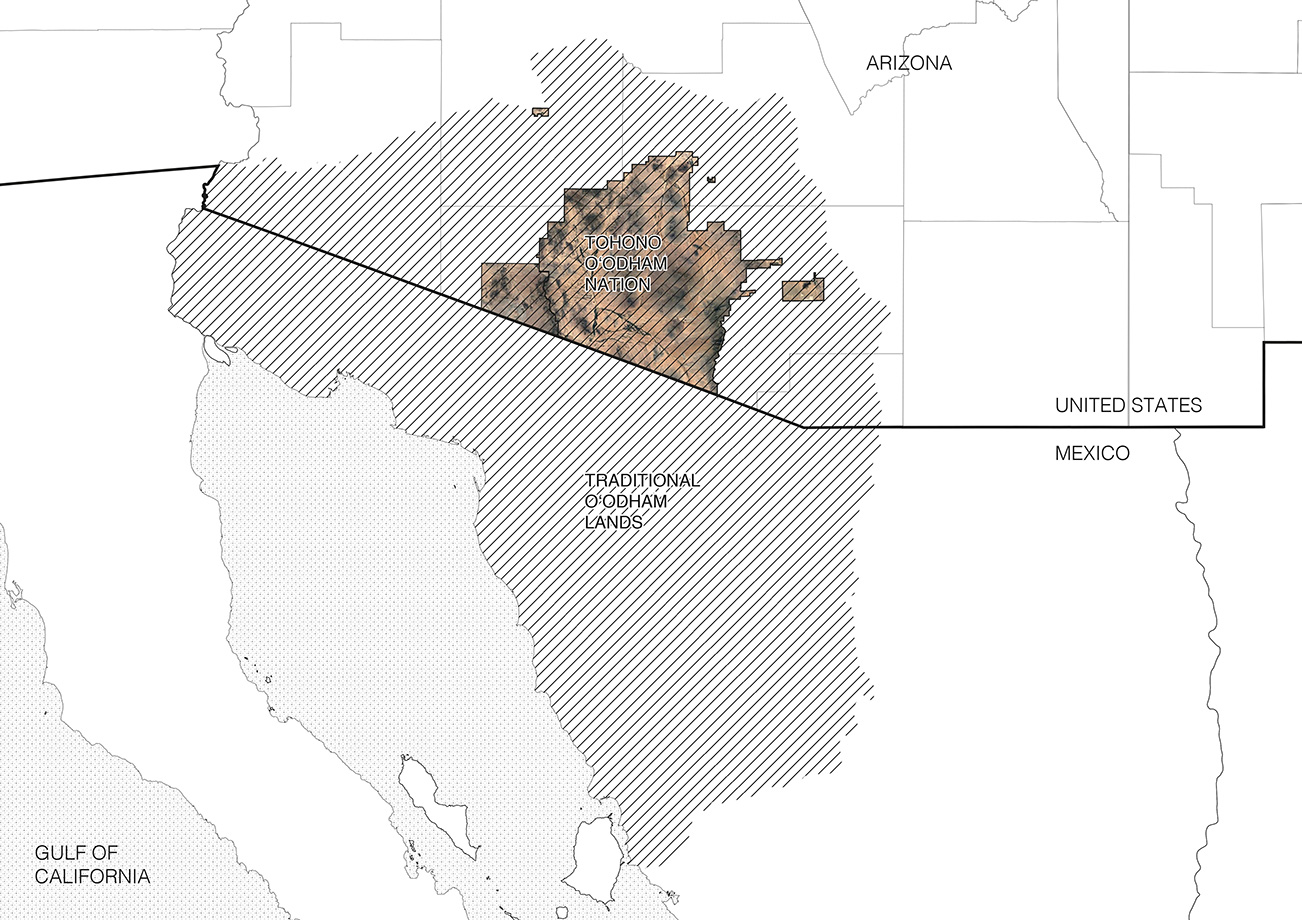

The O’odham traditional lands encompass thousands of square miles of Sonoran Desert in a territory that straddles what is now the border between Arizona in the United States and Sonora, Mexico. Tribal members historically have moved fluidly through this terrain, traveling to seasonal villages, harvesting saguaro cactus, visiting the Sea of Cortez, and performing spiritual walks or runs. The Nation today represents only a tenth of a territory the O’odham inhabited for centuries—a territory systematically reduced through invasion, land purchases, and executive orders that the O’odham, never recognized as a sovereign nation by the United States or Mexico, were not party to. On what was until 1917 O’odham land there is now a United States national park, a United States Air Force base, and a United States border. In short, the United States federal government in one form or another exercises jurisdiction over ninety-one percent of O’odham ancestral lands—lands once understood solely through O’odham traditional knowledge and inhabited through O’odham sovereignty.

Despite the constriction of their land base, crossing the international border has remained a daily activity and was needed to practice religion and traditional way of life, visit family (many of the tribal members have family on both sides), collect traditional food, receive healthcare and education, and partake in a cross-border economy. For this reason, the Tohono O’odham Nation’s constitution determines tribal membership on the basis of a person’s ancestry and not a person’s citizenship. That means someone with sufficient O’odham blood born in Mexico is a member of the tribe—a tribe recognized by the United States government. But post-9/11 Patriot Act legislation has changed this historically open terrain and restricted the mobility of its inhabitants. With the Patriot Act, crossing the US–Mexico border along the Tohono O’odham nation was restricted to three “tribal gates”—Customs and Border Patrol-managed checkpoints, where sufficient documentation is needed to cross. Crossing along traditional, unguarded paths was made illegal. This has produced an incredibly complex and increasingly tight condition of border militarization, where divergent understandings of property, connectivity, and permanence have created an impasse in which indigenous rights to the land are seen as incompatible with the perceived demands of national security.

US Customs and Border Protection mobile surveillance tower in Gu-Vo district, Tohono O’odham Nation, 2017. Credit: Caitlin Blanchfield and Nina Valerie Kolowratnik

In March of 2014, United States Customs and Border Protection (CPB) awarded Elbit Systems of America and International Towers, Inc. (ITI) a contract to design, construct, and deploy Integrated Fixed Towers at an unspecified number of sites in unspecified locations along the Southwestern Border of the United States. ITI and Elbit’s responsibilities extended beyond mere construction and monitoring to in situ testing, ensuring customer satisfaction with their product’s ability “to detect, track, identify, and classify movement on the border.” While sites and numbers remained obscure, the objective of the towers was certainly made clear: They were to be integral nodes in what was becoming an increasingly robust border surveillance apparatus. Supporting agents in the field with “long-range, 360-degree, all-weather, and persistent surveillance capabilities,” the towers would assist CBP in “identifying and classifying ‘items of interest’” near the border. Moreover, the towers were touted as a “technology solution for the distinct terrain within USBP Tucson Sector.”

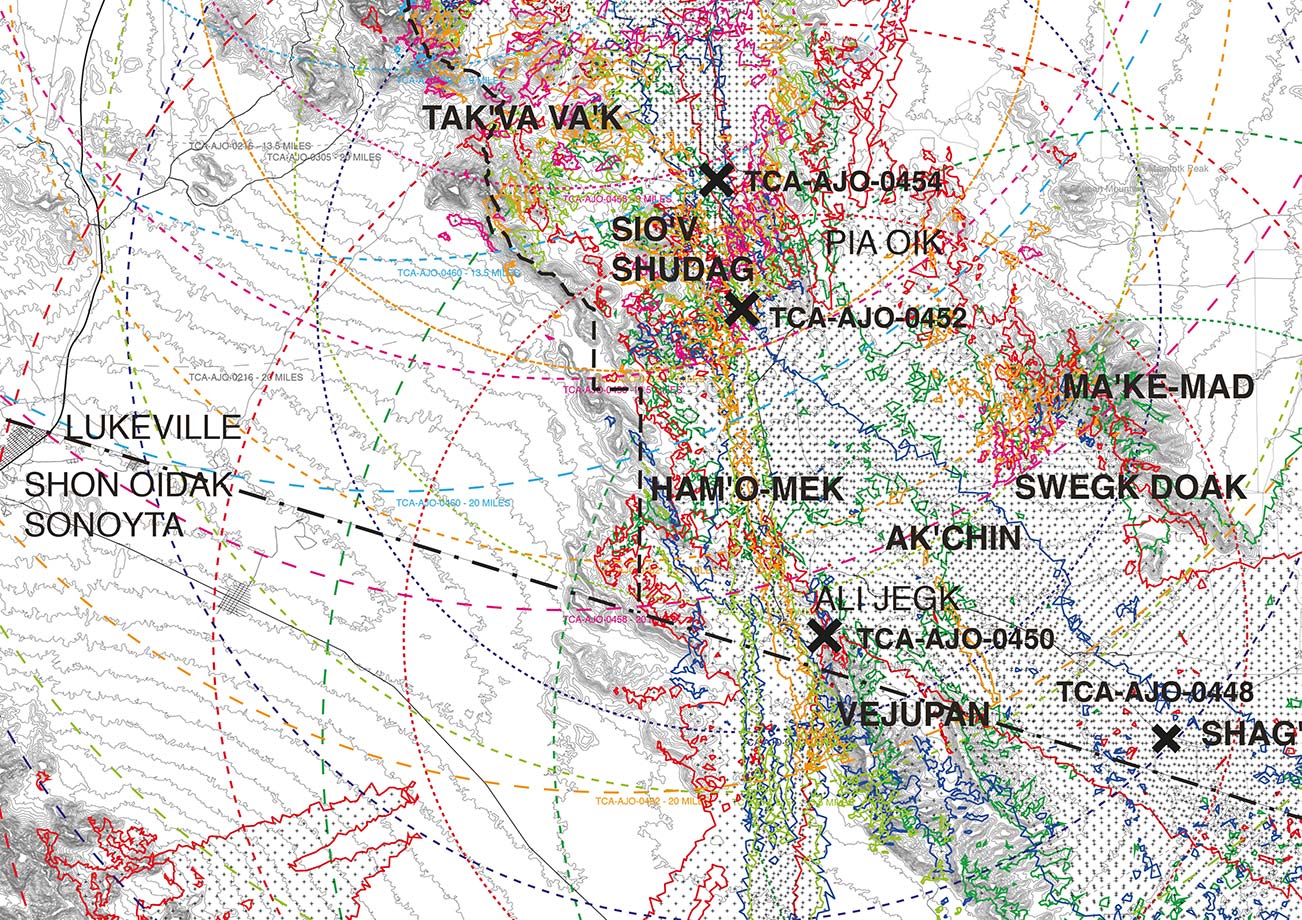

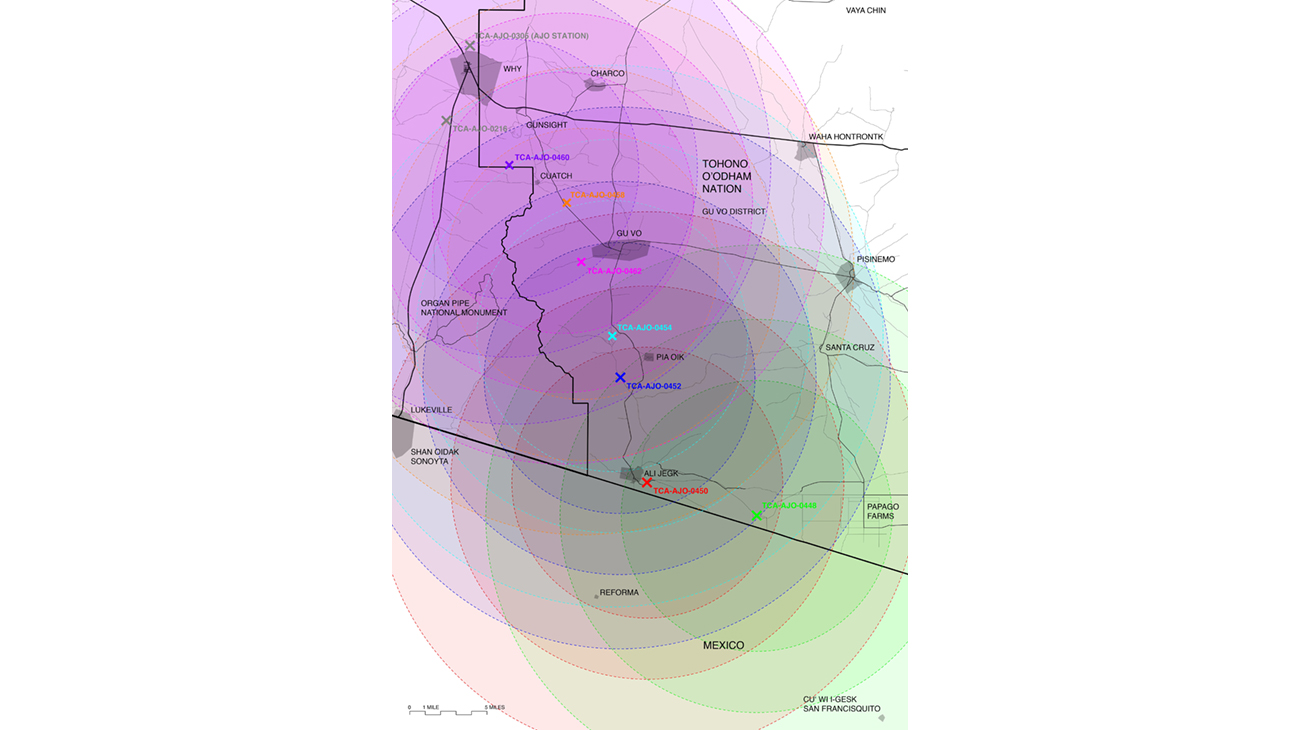

Currently, CBP has proposed to build sixteen Integrated Fixed Surveillance Towers in the O’odham Nation along its southern border with Mexico and its western border with the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. The proposed towers are laid out in a curved line following the US–Mexico border and then turning at its juncture with the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument to extend along the Tohono O’odham border into the interior of the United States.

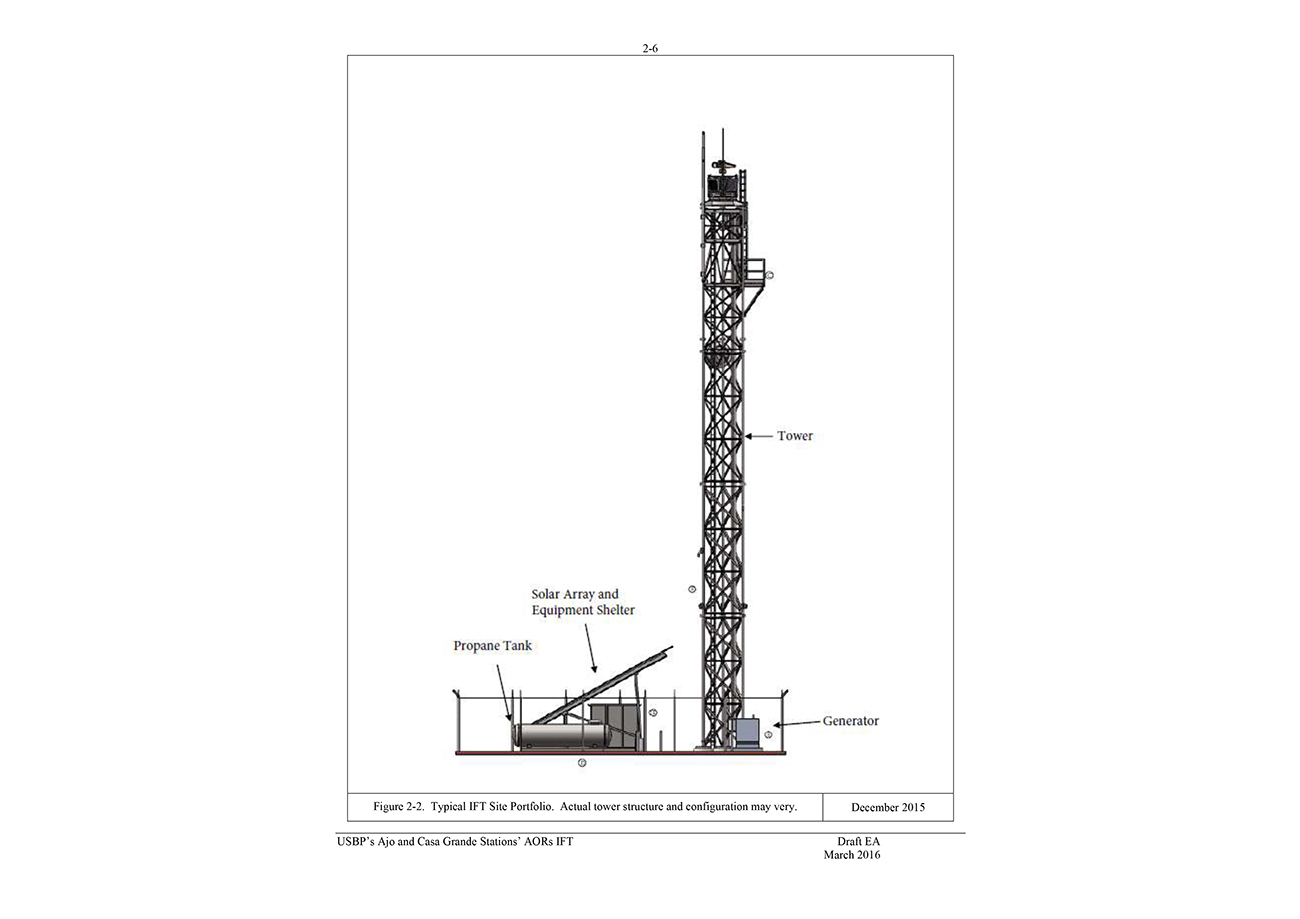

Structurally, these towers are pretty straightforward. One hundred twenty to one hundred eighty feet high, they include a base with a propane tank, generator, solar panels, and equipment shelter. Their footprint is anywhere from 50×50 to 160×160 feet wide and includes parking area. They are surrounded by a fence that would enclose up to 10,000 square feet. A 30-foot-wide fire buffer extends beyond that. Tower access will also include 70 miles of new road (including entirely new access roads), the widening of existing roadways, and drainage ditches. Towers are then hooked up to the grid where possible, necessitating new power lines and fiber optic cables.

But the footprint of these towers extends beyond the perimeter of the fence, and even beyond the roadways that connect to it. The towers will be equipped with a range of surveillance equipment: radio-frequency radars that can detect moving a person within a 9.3-mile radius, long-range video cameras that will capture everything within a range of 13.5 miles, radio-frequency radar that can detect moving vehicle within a 18.6-mile radius, and microwave communication receivers that transmit up to 40 miles. In addition, they hold spotlights and laser illuminators.

Map indicating radii of proposed surveillance towers in Gu-Vo district area, Tohono O’odham Nation. Credit: Caitlin Blanchfield and Nina Valerie Kolowratnik

Site surveying in preparation for the Integrated Fixed Towers has already begun to have an impact on the land and daily life in the Tohono O’odham Nation, and it’s no coincidence, then, that along with the construction of towers come detention facilities for people apprehended crossing the border. It also requires little stretch of the imagination to understand that the infrastructure apparently needed to support construction and maintenance of towers is also quite useful in the pursuit of “items of interest”—be those local residents, US citizens, or migrants entering the country legally or illegally—and the persistent, low-grade harassment of permanent population in the borderlands.

The proposed towers are a great incursion on the sovereignty of the O’odham—the most recent in a chain of systemic rights violations that date back centuries. Not only do the towers’ impact extend far beyond their physical footprint, the area of their right-of-way—a considerable 6,428 acres—and the border patrol they bring with them are just one more instance in a very long history of the United States government militarizing and occupying Native American land.

An infrastructure of surveillance—which includes patrolling bodies—and its attendant culture of fear has changed the tribal relationship to the land, with significant cultural consequences. The towers, like the border fence, become agents of indoctrination, material mechanisms used to assimilate tribal members into Western culture, with divisive consequences. The increased presence of border patrol agents, for instance, has caused young O’odham to spend more and more time at home instead of out on the land. By claiming the tribal “common” land of the reservation as the space of surveillance and militarization—as property of the federal government and within its sovereign territory—border patrol forces tribal members into a space that they can easily define as private property of their own: the house.

By forcing tribal members into a lifestyle centered around private property, border surveillance not only has immediate consequences in terms physical and psychological well-being, it also ruptures intergenerational ties and spiritual knowledge and results in cultural disconnection to the land for its inhabitants.

In April 2017, CBP published an environmental assessment, as the final step of the National Environmental Policy Act process they followed, stating that the Integrated Fixed Tower project will have no considerable impacts on the ecosystem or the tribe. As the widespread opposition to these towers by many tribal members and several traditional leaders shows, this is not the case. Because of their strong connection to the land, a connection border militarization is already eroding, residents of the tribal districts affected by the towers feel the towers’ presence would be catastrophically disruptive to spiritual practices and daily life, as well as irreversibly destructive to a landscape they hold as sacred. According to O’odham beliefs, ceremonial pottery and human remains should not leave their place of entombment. Uprooting them at all is extremely offensive—let alone expatriating them to a conservation center in Tucson where the tribe must petition to have them returned. Road clearing and surveying has already uncovered countless pieces of pottery and of bodies. It has also stunted the growth of mountain grasses and displaced deer, tortoises, sheep, and jaguars from their migration routes and habitats, impacting the O’odham hunting rituals that are integral part of the O’odham traditional calendar.

How, then, can the expertise and resources of architects and scholars be used to help advocate against these towers? With support from the Norden travel fund, we visited the Tohono O’odham Nation to meet with tribal elders, youth activists, and the tribal government to learn about the effects of surveillance infrastructure and the nature of their opposition to the integrated fixed towers. We traveled the land to survey the proposed locations of these towers and learn about the significance of these sites to the O’odham people. In collaboration with tribal elder and activist Ophelia Rivas, we discussed how new forms of architectural representation and language could be used in the effort to advocate against the Integrated Fixed Towers locally and to a broader public, and developed strategies to do so.

Through representations of current and proposed border enforcement infrastructure and their different techniques of surveillance, our project works towards an understanding of how this infrastructure operates in different administrative zones and its impact on existing cultural and ecological systems. The analytical mappings and visualizations and oral history-based writings that have come out of our research and experiences on the Tohono O’odham Nation will be used as an activist tool to help community members rally opposition to the proposed towers.

Though absolutely politically urgent, the terms of border debate in the US can often silence the voice of indigenous communities who live in the borderlands. In the rub marks of such acts of erasure, we propose new forms of representation that more accurately reflect indigenous understandings of land and sovereignty, and therefore the full extent of border militarization. To this end, our project for the Norden Fund, in collaboration with Ophelia Rivas, developed a framework for an alternative environmental assessment that, through maps and text, will articulate the wide-reaching political and social impact of the proposed towers, and that can be used as an informational tool to advocate against them.

Explore

Mexico’s Traditional Housing Is Disappearing—and with It, a Way of Life

Mariana Ordóñez Grajales and Onnis Luque are fighting to preserve their country's vernacular architecture.

Potable water and local power struggles in Honduras

Timothy Kohut reflects on alternative visions for community development in Tegucigalpa.

AGENCY lecture

Ersela Kripa and Stephen Mueller, founders of AGENCY, discuss their work.