On the table: Dinner with Chris Baribeau, Josh Siebert, David Seiter, and Jason Wright

A conversation about organic business growth, design advocacy, and the future of landscape architecture.

The League’s annual Emerging Voices program recognizes eight firms with distinct design voices. In March and April, each firm delivers a lecture, then joins prominent architects, critics, and others in the industry for dinner and informal discussion.

In the following, David Seiter of Brooklyn landscape design firm Future Green Studio and Chris Baribeau, Josh Siebert, and Jason Wright of Fayetteville, Arkansas, architecture practice modus studio discuss organic growth, design advocacy, and the future of landscape architecture.

Jing Liu, SO – IL: We started our firm in 2008, the same year as modus and Future Green. For us, that starting point very much framed the practice. When everything is seeming to collapse and disappear, how do you rise from the ashes, in a way? And what comes next?

David Seiter, Future Green Studio: 2008 was a really unique time. One year I bought an apartment. The next year I opened Future Green. The next year I had my daughter… All these worlds were colliding. But there was this opportunity for emerging firms to establish themselves by being younger, hungrier, cheaper.

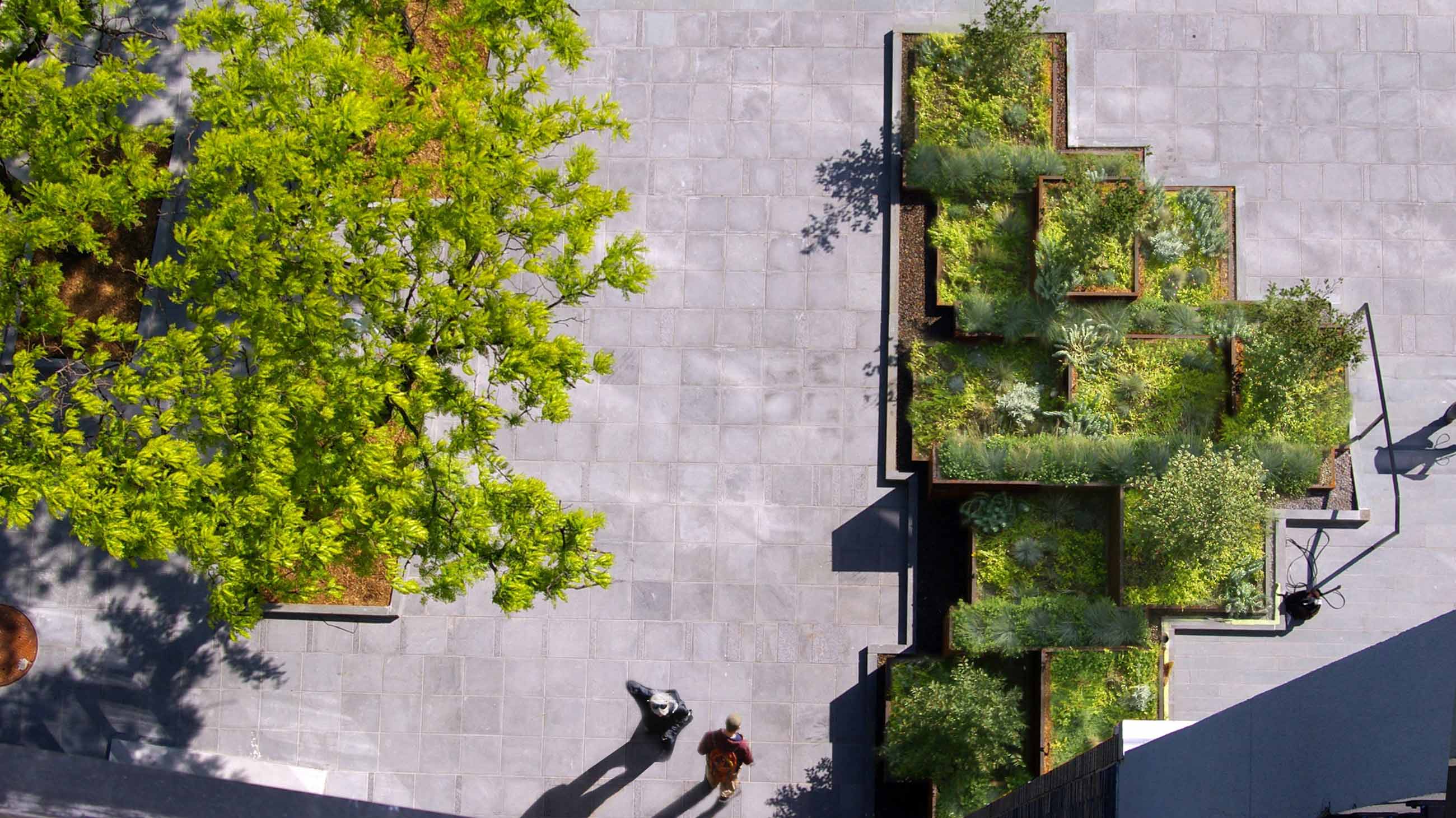

We’ve now reached a point where we’re able to conceptualize what’s next. It wasn’t intentional that we got involved in designing landscape in buildings. I thought I would do parks and gardens: larger spaces.

After the example of the High Line, we’re beginning to look more at streets, understanding that these linear parks connect neighborhoods in a way that a different type of edge park—like Hudson River Park or Brooklyn Bridge Park—can’t.

Maybe streets are the foundation of new public space. There’s this huge realm that’s just under-designed.

New York has gotten more open to landscape architecture in the last 10 to 15 years. Before, you had to do everything typical: typical bench, typical paint colors, typical everything. Now things are starting to open up. American parks have been about refuge. Now you’re beginning to see streets more like the Jane Jacobs theater of urban life.

We’re thinking about creating a manual that’s within the DOT’s [New York City Department of Transportation] language that can be a toolkit for better design strategies in the public realm.

Chris Baribeau, modus studio: For us, 2008 was just a lean and mean time. Our motto was, “We will not be outworked.” We were hungrier, younger, more energetic, more enthusiastic. Dumber, for sure.

We’re in an economic bubble in Northwest Arkansas, thankfully, as weird as that sounds—the area is home to three Fortune 500 companies, so there’s a strong underlying economy. So in 2008 we just thought, “Hey, we’re going to ride this thing out.” We did. We steadily grew year by year. Along the way started a fabrication component as well.

We’ve been talking about what’s next a lot in the last few months. I think the answer is maybe, how do we take fabrication or building further? At what point do we fully build our own projects? That’s a conversation we’d like to have—going from the widget to a full construction, like we did with our own office renovation. We managed that completely, but how do we take that to a new building?

We’ve worked with a lot of great contractors and consultants along the way, but at some point, we get tired of the roadblocks.

Liu: Both modus and Future Green are pushing the limits of design in their contexts. But how far can you push? I’m curious when you would say no to a project or an idea.

Baribeau: We’re at a pretty luxurious point where we cherry pick the parts of our work that we want to take on.

I don’t know where to draw the line. Jason?

Jason Wright, modus studio: It’s not a glamorous answer, but the reality is, we’re not going to do a project if we can’t staff it right. We’re not going to staff up for projects so that when the project’s done we just lay people off willy-nilly.

We invest highly in our people so that craft and quality are always going to be there. I’ll say no to a $300,000 fat job if it means that I’m going to have to hire 17 people that I’ve never met before and won’t be able to keep on the staff.

It goes beyond design. There’s that human component that we don’t like to talk about—real, living, breathing folks out there that do the work. Where we draw the line is, we do the stuff that we know we can do well with the help that we have, and we try to organically grow.

In 2008, in Kansas City, when I was there, over 100 architects lost their jobs in firms that specialized in giant stadiums. All of a sudden that all went to shit and they just laid a lot of people off. That’s stuck with us.

Jeffrey Taylor, Taylor and Miller Architecture and Design: We’ve been building since before 2008. I feel like one of the things that limits us in our ability to deliver a project is the shortage of young people who are willing to work with their hands.

I don’t know if that’s something you guys are experiencing, too, but I’m worried about it for the industry, frankly.

Wright: You should start recruiting at the University of Arkansas! I don’t think we have a shortage of talent in the Midwest in general.

Florian Idenburg, SO – IL: Knowing Jing, I think her question about what’s next is not just what’s next for you, but for what’s next for society?

In Arkansas, I can imagine you’re the poster boys for individual entrepreneurship, and that there’s a strong interest from government and society to say, “Hey, what can we do to partner, to get maybe 600 students to learn a skill?”

How can design be part of a larger retooling of certain areas of the country?

Liu: To build on that: I’m from China, and Florian and I actually met in Japan. There’s a really rich architectural tradition in those countries, and it’s passed on by people, right? It’s the villagers: grandparents telling stories to the kids, and then those traditions are lived in daily life.

It’s really difficult to translate that beyond the village. These links are broken down in this globalizing world.

So yes, as a reaction to a lot of the things that have happened in the last few decades, we are regaining this faith in craft, in the passing down of the narrative, in caring for the community. How far can we go?

Josh Siebert, modus studio: I think some of that answer is education. For instance, in the rural school districts where we work, they may not have had a new building on the campus for 30-plus years, so they typically will come into the conversation with, “How much can I do for as little as possible?”

Fair enough. Everybody has a budget. But we are plagued by the fact that our state funds projects on an assessment of the county value. They may only budget, and get, $160 a square foot. The school districts, they don’t make money. They don’t have other assets to parlay into doing more.

So you’ve got to educate the school districts about how to raise funds to provide good design within the budget they have, or challenge them to go a step further.

You get one shot. In Green Forest, the middle school we designed was the first AIA award in the state that we know of for a K-12 education facility. Since then, the community as a whole—2,200 people—is asking us to do more projects. They’re doing a city hall. They want to do a community center. It’s starting to change the face of what design means to the community.

So it’s just being out there and talking about what design really means and how it impacts your daily life—that’s we’re trying to do.

I think the next step for us is: How do we get involved in the politics side of helping people understand that the budgets are misallocated to begin with? How can we change that? Are there other income sources?

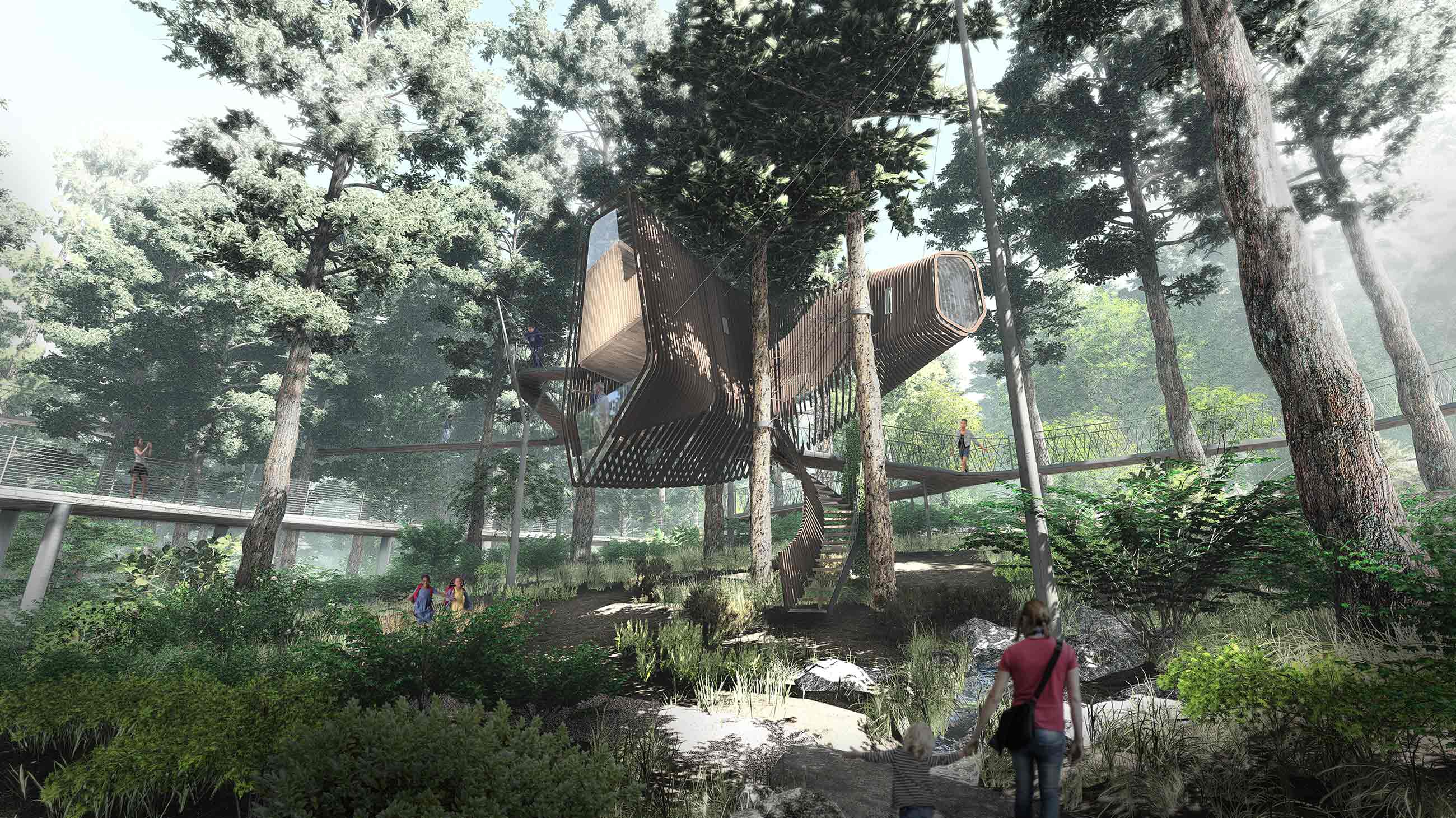

modus studio | Garvan Woodland Gardens Children's Educational Treehouse, Hot Springs, Arkansas. Credit: modus studio

Seiter: At Future Green, we’ve seen a real interest in young people returning to a tactile workplace where they have a connection to plants and site and material.

When I came out of grad school, I worked at Hargreaves Associates, which was an amazing education, but I also felt like I didn’t really have those connections. For me that was essential to create.

Now we have a lot of staff that come out of great landscape architecture schools like Harvard and Penn and Berkeley and UVA. A lot of those schools focus on extremely large-scale sites—20-plus acres. There’s no planting design. There’s no constructability class. There are no small-scale sites.

A lot of people are really hungry for applied design. They come to Future Green excited about the opportunity to see things being made, to interact with laborers, with woodworkers. That informs their design sensibility to the point where they can carry that hands-on knowledge back to a larger site.

That play of scale is really essential to a designer’s education. You’ve got to think about systems and city-wide research, but you’ve also got to be able to dial it down to site specificity. Each site is unique. The architecture plays a big role, but also the social, historical, environmental layers. How can we unearth all that and bring it to the forefront?

I’d say for the future visioning stuff, one thing is that whether you’re in Japan or Moscow or New York, the same plants are emerging. There’s 85% to 90% consistency of plant types in urban environments around the world. It’s not about, like, “Climate change is driving the types of plants that are emerging”—it’s our human degraded condition. It’s the same thing that happens with animals. These plants coexist alongside of humans, taking advantage of the opportunities that humans offer.

Siebert: Like rats.

Seiter: Like rats, or pigeons, or squirrels. How can we give the rats a voice? [laughs]

No, but authentically, for emerging cities… for me, it’s not about taking landscape too far, it’s about looking at places in the global south where there’s this huge densification, but it’s completely devoid of nature. There are no trees. There’s nothing. What’s the inversion of that, and how can we present that as an alternative reality?

Diana Darling, The Architect’s Newspaper: In modus’s projects, there’s a lot of landscape involved. Is that something you do internally?

Siebert: We search for landscape architects to work with, and we fight for that part of the project. That’s one of the biggest battles on the K-12 market, because they’ll say, “Well, we’ve never had that. Why do we need it?” We really push it and say, “You’ve got to think much broader than, ‘Oh, it’s a bunch of plants.’ It’s much more.”

Darling: I grew up in Texas, and I go back probably every other month. There’s a shift in many of these towns in the South. They have these incredible projects going on. They’re nicely designed, and they’re big in scale. It’s interesting to see how it’s affecting the community. They get one project, it looks great and everybody loves it, so they’re hungry to do more.

Peter MacKeith, Dean at the Fay Jones School of Architecture, University of Arkansas: To connect this to the longer history of Emerging Voices, about 1982, the year Emerging Voices was first awarded, you have to think where architecture culture was: rather obsessed with surfaces and a form of historical thinking in representation, and also in the stage of an economy with large-scale complexes such as Battery Park City.

I recall making a proposal at that time for the Yale School of Architecture journal, asking to focus on Alvar Aalto, Mario Botta, Steven Holl—all known as lesser architects at that point, regional in character—and being told that these were unnecessary practices to focus on because they were far too materially focused.

Interestingly, if you think on the 30+ history of Emerging Voices, if you did a word-cloud analysis of every presentation, you would probably come up with an emphasis on specificity, attentiveness to site, craft, material, techniques of construction, scale, proportion. They’re not entirely all regional practices, but nonetheless very, very specific practices.

This is increasingly the kind of design that young people at our schools want. They want to have their hands on materials. They want to be speaking and working in the interests of specific communities, and they’re very concerned about ecology, both local and global.

I think we’re all advocates, knowingly or unknowingly, for this particular frame of thinking.

Conversation edited and condensed.

Explore

A walk through the University of Arkansas School of Architecture

A tour of the University of Arkansas architecture building with Marlon Blackwell and Tom Phifer.

Material flows, ecosystem growth, and urban landscape renewal

Paul Mankiewicz explores ways to improve the environmental, infrastructural, and economic health of cities.

On the table: Dinner with Manuel Cervantes Cespedes, Ben Aranda & Chris Lasch

Emerging Voices winners discuss constraint, minimalism, and how to "client-proof" a building.