The simplest move for the biggest impact

An interview with SPORTS, winners of the 2017 League Prize.

The League Prize, an annual competition that asks young designers to respond to a given theme, has marked an important milestone in many architects’ careers since it was established in 1981. Winners showcase their work through a lecture series and exhibition.

SPORTS, a firm based in Syracuse, New York, was one of the 2017 prize recipients. Cofounders Greg Corso and Molly Hunker discussed their work with the Architectural League’s Akiva Blander and Catarina Flaksman.

Blander: This year’s League Prize theme is “Support.” What does this mean to you?

Corso: We were trying to wrap our heads around how that fit into our practice, and then it occurred to us—we were thinking about support as an ideological proposition. One supports something, whether it’s an idea or a sports team. In architecture, you might support a certain solution out of habit, or because it’s the status quo, or because it’s how you were trained.

We started thinking of our relationship with support as a kind of rejection of that idea. We strive to be more flexible in how we think about design. This can mean learning from a variety of different facets of the discipline, or other disciplines. It also means thinking about projects in a multiplicity of ways, considering a variety of solutions that may or may not align to a certain position in architecture.

Hunker: Continuing the sports analogy, if support is a person who cheers for a team win or lose, we felt like our work was more about just supporting good plays. We were thinking about the spectacle and beauty of the good play, and how that might relate to the idea of multiplicity within different architectural contexts.

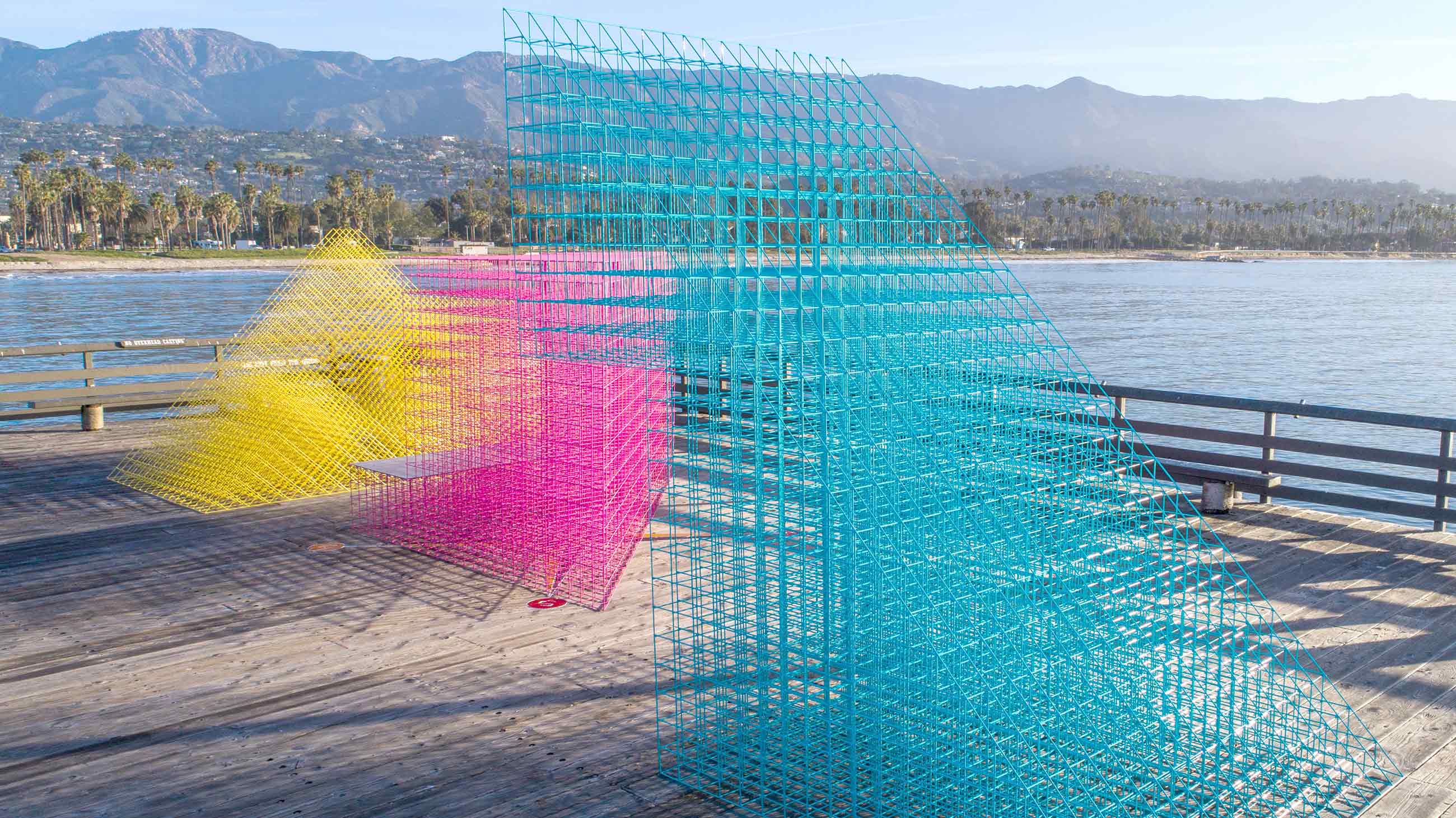

For the League Prize exhibition, SPORTS presented three projects in three ways (line drawing, 3D model, and photograph), aiming to reveal different layers of information in each. Credit: David Sundberg/ESTO

Blander: Many of your projects blur the boundaries between architecture, installation, and public art. How do you see the relationship between these different domains? How does that relate to the way people experience each project?

Corso: That’s just a general way we think about architecture—as blurring with so many other things. For us it’s not intentional, but rather a response to the opportunities we see, just in the same way that our colleagues deal with architecture blurring with politics, environment, aesthetics, whatever. I think that’s just the nature of working today. We graduated from school when there was a serious economic crisis and both found ourselves working for artists. So we were able to learn multiple ways to address a problem.

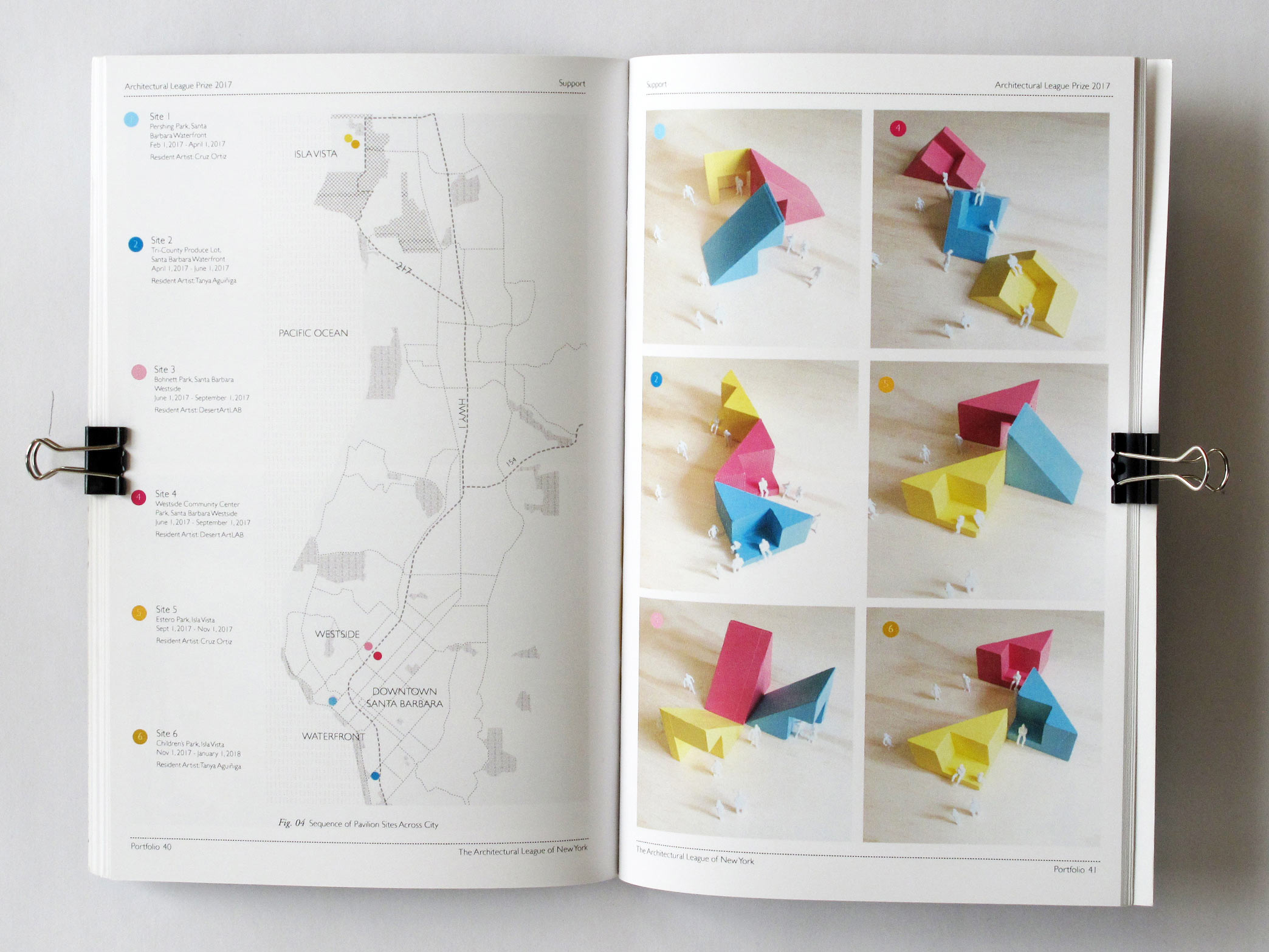

Pages from the SPORTS League Prize competition entry. The project featured, "Runaway," won a pavilion competition organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara.

Hunker: Also, it’s a result of the scale at which we’re working, which has been determined thus far by things that we can build ourselves. We graduated and, despite the recession, wanted to build something right away; we wanted to get our stuff into the world. That’s mostly been small-scale work—installations, pavilions, etc., which I think inherently combine ideas of art and architecture.

Blander: Your projects present a playful approach to architecture; even the titles are playful. Do you think about this in terms of serving audiences of different ages?

Hunker: There’s definitely a lightheartedness to the way we think about architecture. We like to think about how our projects can produce delight, particularly in these times, when delight is somewhat hard to come by. We’re interested in broadening our audience beyond one that might typically engage with capital-A architecture. So we are thinking about how accessible projects are visually, and in terms of use and function.

Corso: A lot of the project titles come from music references. We tend to think about matching a project’s sensibility with other artifacts rather than being super explicit and didactic about what the project is. It allows us to have a little more fun and paint a larger picture.

I don’t think there’s any intentional relationship in terms of the age of the person who would access the project, though.

Hunker: Maybe the opposite, actually. Thinking about the delight of a kid and the associated playfulness—why is that just for a child? How can we broaden that? We take our work incredibly seriously, but how can we bring a kind of light-hearted feeling into the world, changing the way the space feels for someone of any age, of any background?

With the titles, there’s a relationship with sources of inspiration. We look at architecture, of course, but we find ourselves referencing non-architects more often than architects—artists, musicians. With the music references, there’s often a resonance with a particular artist: the way they work, the way they construct lyrics.

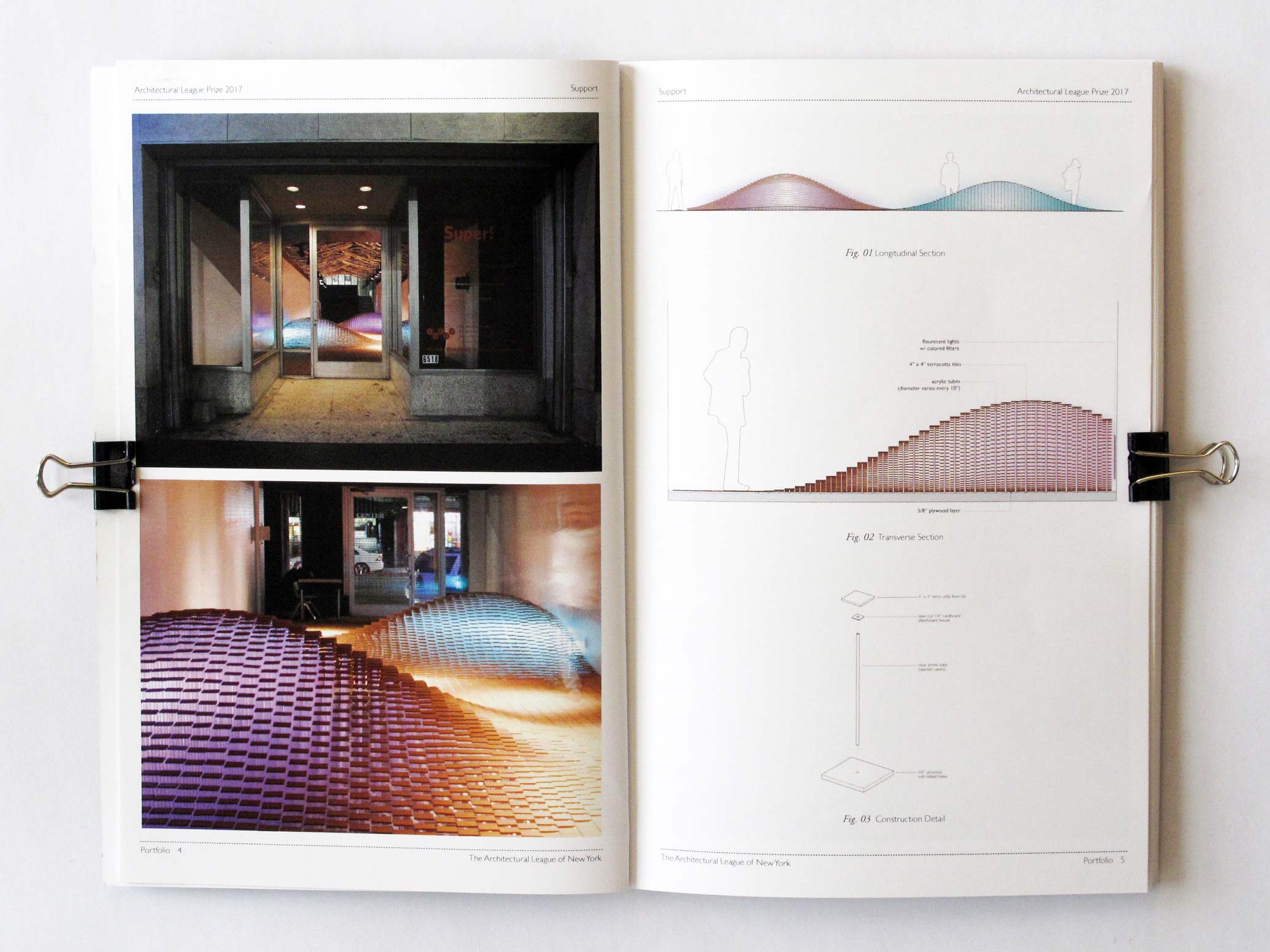

Pages from SPORTS League Prize competition entry. The project featured is "Stay Down, Champion, Stay Down," a temporary installation in a Hollywood storefront gallery.

Blander: Your projects are characterized by repetition of a certain form, pattern, or material within a project—a simple 3D grid in Runaway, or those tiles in Stay Down, Champion, Stay Down. Can you talk about the design process and how it relates to the construction and finished product?

Corso: It’s influenced by a number of factors, from buildability to budget to an interest in working through some high-economy moves, or something very small that has a lot of variation.

A simple gesture can actually be quite robust as a design proposition. We can build some complexity into the project in a very controlled way without it being a complicated mess. We use simple language, and hopefully potent phrases and words, to create a sentence that we think is much greater than the sum of its parts.

Hunker: It’s about doing the simplest thing we can that will have the biggest impact in the particular context, for the particular audience, given the particular goals of the project.

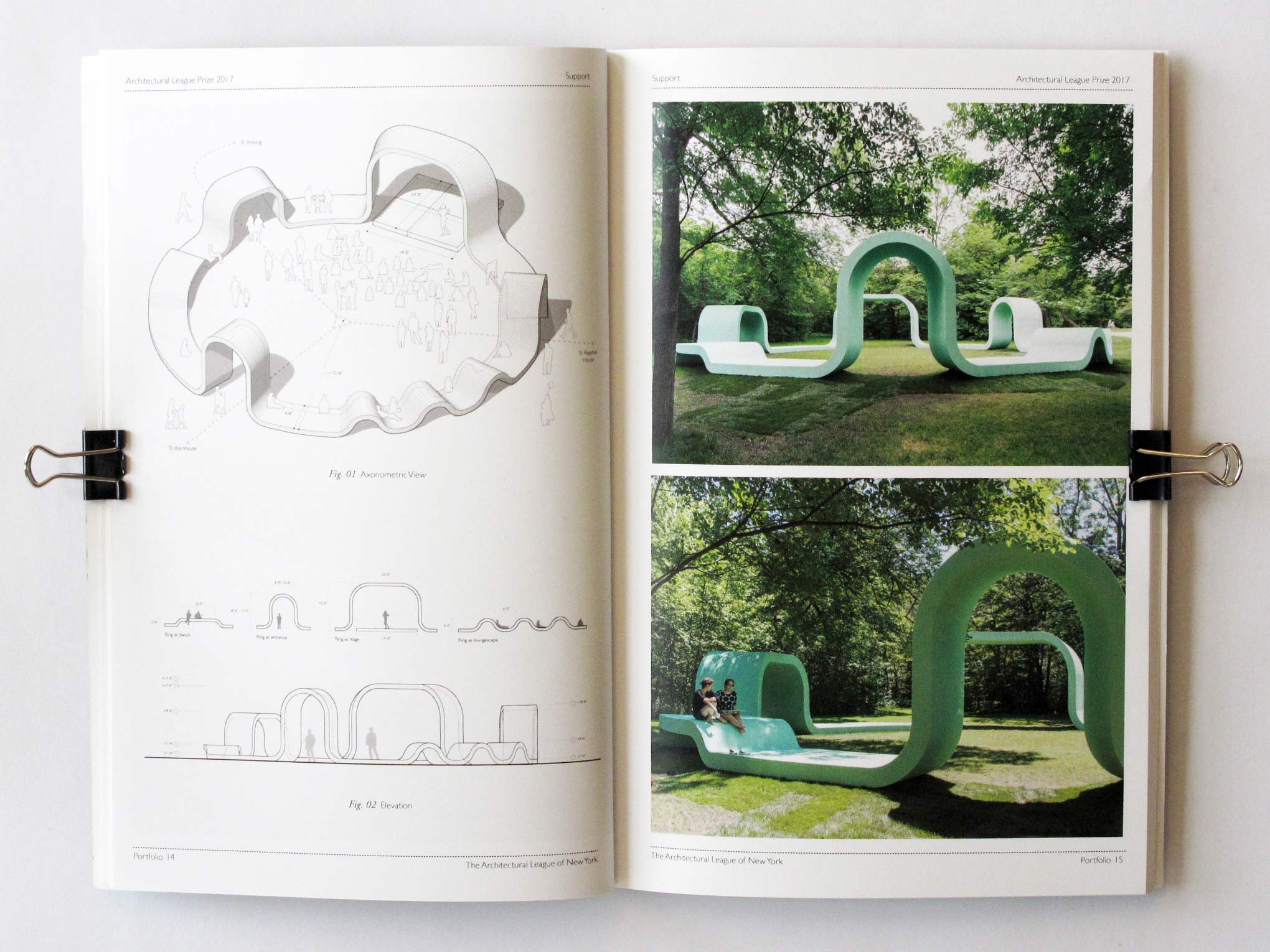

"Rounds," a temporary structure in Lake Forest, Illinois. The design won the 2016 Ragdale Ring Competition. Credit: Nick Zukauskas

We look at a lot of Japanese architecture for this exact purpose—these insanely simple moves that are just so powerful. How can we take a single system and just do that one thing to a point where it satisfies the many, many layers of requirements of the project?

Corso: We also look at Nirvana or the Beatles, where you have four chords and you make some song that changes the course of music. We’re inspired by people that build something up from such small pieces.

Blander: You have very ambitious intentions, yet you’re clearly very concerned with the pragmatic constraints of working with monetary and material restrictions.

Hunker: Part of that is that we really want to build the work. With each project we’re thinking, “We have this idea, how do we actually get this into the real world? How would we make this? What materials would be coolest here? What color would this be?”

Corso: Part of it is also because material has long been of interest to us. We’re super interested in the details that come along with that scale.

There's definitely a lightheartedness to the way we think about architecture.

Blander: The use of bright colors is a common feature in your work. Could you speak a about how color relates to the context of each project?

Corso: Color is just another layer to explore in the work. It’s completely collapsed with the idea of material, obviously, and ideas of the atmospheric elements or iconicity.

We also think… Everything is a design decision. We’re always telling our students, “Your white project is a conscious decision. That’s not a default.” If you look at our early project tests, they go from white to black to all these different palettes of colors and patterns, and then we end up with something that is integral to the project.

Rounds has a language of green on green, artificial and natural. And that’s a physical pigment, versus Stay Down, Champion, which has to do with the color of light of Hollywood Boulevard—neon bright.

Hunker: We considered many, many colors and patterns for Rounds, for example. This is where we spend a lot of fun time in designing: rendering every color and patterns of splatter paint, dots, stripes, other graphics.

Ultimately, we drew the decision out to the last second. We brought all our samples to the site and actually started building the project before we chose that final color, because it’s a historical site and we felt that we needed to get a sense of the place and the people there. It’s in this amazing protected area of untouched Illinois prairie. The natural landscape became a more robust part of the project than we had been thinking when we were in the computer. That contrasting relationship became of great interest to us.

Corso: We were going between high contrast and low contrast. Once we figured out what we were interested in we had all of our students there building it with us, and we still had nine mint greens out for everyone to talk about.

Blander: How do you see SPORTS evolving in the next few years?

Corso: I don’t know if this is intentional or not, but our projects have increased in scale. We are going from installations to something that might be more programmatic to proposals for buildings. We haven’t changed our approach, but we are interested in the larger scale, and in the idea of permanence.

Hunker: Yeah, this goes back to the art / architecture question. We see ourselves very much as an architecture practice, even though the work could be characterized as art or public art or installation. We’re deeply interested in buildings and how the projects we’ve done have tested ideas that could operate at a variety of scales. How they might reposition themselves in the larger-scale project is yet to be tested, but that’s definitely our hope.