Lower Rio Grande, New Mexico

The Aftermath of the Manhattan Project in Southern New Mexico | Socorro County

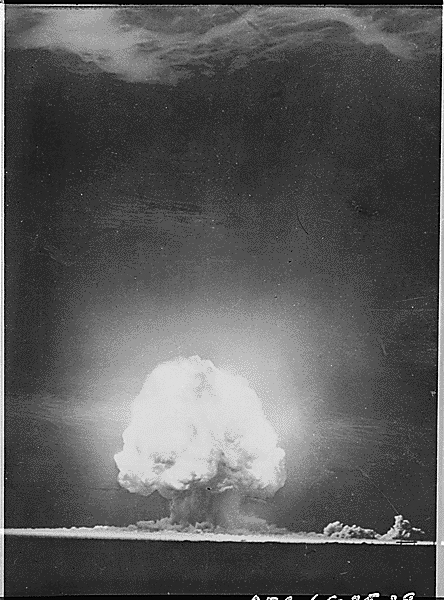

At 5:30 a.m. on July 16, 1945, the world’s first atomic bomb was detonated over what is now known as the Trinity Site, creating a shock wave that radiated 160 miles outward. The site, today located at White Sands National Park in Socorro County, was selected due to its remote location and weather conditions. While the bright light emanating from the explosion could be seen all the way to Albuquerque, 130 miles away, the test remained highly classified, and therefore a secret to the public—and to many of the 130,000 scientists and engineers who worked on it. To avoid instigating panic, the government chose not to evacuate nearby towns. The detonation site remained closed off until 1953 due to its high radioactivity. In 1975, it was designated a National Historic Landmark; today, the site allows visitors access twice a year.

Groups like the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium (TBDC) are working towards the passage of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act Amendments, which would bring healthcare coverage and compensation to the New Mexicans whose health has suffered from the effects of the explosion. According to TBDC’s research, the explosion caused rare forms of cancer for many of the 30,000 people living in the area.1Learn more here.

In this interview, Tina Cordova, the group’s cofounder, discusses the effect that this explosion had on the species, land, and inhabitants of the area and describes the work that TBDC has been doing over the last two decades to raise awareness and provide support for those affected. —Ane González Lara, Diverse Peoples, Arid Landscapes, and the Built Environment report editor

Video portrait of Tina Cordova. Credit: John Acosta

Ane González Lara interviewed Tina Cordova in 2020.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Ane González Lara [AGL]: It would be great if you could start by explaining where the Trinity Site is and give some context to its historical significance.

Tina Cordova [TC]: The Trinity Site is in south central New Mexico, approximately 35 miles west of Carrizozo and about 45 miles north of Tularosa. The closest town is San Antonio, New Mexico. The Trinity Site was established by the Manhattan Project in the nineteen-forties to test the nuclear device that was developed through the Manhattan Project, and July 16th this year has been the 75th anniversary of the Trinity test.

Watch a video of the Trinity Explosion on the Los Alamos National Laboratory YouTube Channel.

The bomb that was developed and tested was a plutonium–based bomb that was detonated at about 5:29 a.m. on July 16th, 1945. The blast produced more light and more heat than the sun. The detonation was an enormous event, and what made it so unique is that it was a top-secret project, so there was no warning given to anybody before or after.

As to what took place, one of the most common things that the people that I’ve spoken to told me is that they thought it was the end of the world. Another common thread about the history that has been told to me is that their mothers, thinking that it was the end of the world, got on their knees and started praying the rosary. It’s hard to imagine, because if an event like that took place today, literally in your backyard or in close proximity to where you live, we would know within minutes what just took place. But people knew nothing of what it was, and they didn’t know anything about what it was for years. After the bombs were dropped in Nagasaki and Hiroshima it was disclosed that it was a nuclear blast, but people didn’t understand what that meant.2“The Trinity Test | Historical Documents,” accessed October 25, 2020. 3“Science Source – Eyewitness Account, Trinity Atomic Test,” accessed October 25, 2020.

Trinity Explosion at White Sands, Alamogordo, New Mexico, Source: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/558571 . Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

The fireball that was created by the blast ascended over seven miles, past the atmosphere into the stratosphere, and was visible from hundreds of miles. It was just this huge, amazing explosion that rocked the earth.

The location of the Trinity Site is in an area called the Tularosa Basin a very large flat basin area that lies between two fairly significant mountain ranges to the east of what is called Sierra Blanca. Sierra Blanca is the highest, most southern peak of the Rocky Mountains, and it’s over 12,000 feet. The cloud that ascended went so far up into the stratosphere that the ash that rained down from that blast exceeded Sierra Blanca and dropped into communities on the other side.4Thomas Widner and Joseph John Shonka, “Final Report of the Los Alamos Historical Document Retrieval and Assessment (LAHDRA) Project,” Chapter 10, 2009.

AGL: What is the magnitude of the area affected by the explosion?

TC: The thing that is important to know about this particular bomb is that the government of the United States never repeated a test like this. There were specific reasons why the test produced such massive fallout.

It’s really important to understand the history of this. It was the first time a nuclear device was ever detonated, and they had these very rudimentary Geiger counters to register radiation levels. They placed soldiers in Carrizozo, San Antonio, Socorro, Tularosa, Alamogordo . . . with these Geiger counters. But when the Geiger counters started going off the charts, they called all those soldiers off and asked them to evacuate the area. The Geiger counters didn’t even remain in place for 12 hours.

This bomb was incredibly inefficient. It was the first time a bomb had ever been tested, so they overpacked it with plutonium. They used 13 pounds of weapon-grade plutonium, which has a half-life of 24,000 years. However, only three pounds were actually necessary to cause the fission process. The other ten pounds went into the fireball that I described earlier that went over seven miles into the stratosphere.5Widner and Shonka.

Structures at Trinity Site map, HAER NM,27-ALMOG.V,1A- (sheet 2 of 11) - White Sands Missile Range, Trinity Site, Vicinity of Routes 13 & 20, White Sands, Dona Ana County, NM. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The bomb was on a platform 100 feet off the ground, so the blast had nowhere to go. It intercepted the earth, and then it took up an enormous amount of dirt, sand, and incinerated animal and plant life. Because it melted the earth and sand it created what’s called trinitite, a green glass-like radioactive substance that coated the area where the bomb was detonated. The only place in the world where trinitite exists is in the desert of New Mexico. At some point, I understand that it was in the ‘60s, they bulldozed all of that trinitite, but we don’t even know what they did with it.6Susan K. Hanson et al., “Measurements of Extinct Fission Products in Nuclear Bomb Debris: Determination of the Yield of the Trinity Nuclear Test 70 y Later,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, no. 29 (2016): 8104–8108.

Whatever goes up has to come down. So now you have this ash that, according to the firsthand accounts and some scientists, fell from the sky for days. To understand the effect it had on people, you have to understand the way people lived in rural New Mexico in 1945. We didn’t have running water; we didn’t have a grocery store, because people didn’t have refrigeration. As far as food is concerned, they ate the food they grew from orchards and gardens. It was July, so they would have been at the height of their growing season. They also raised all of the animals that they ate. If they didn’t have animals available, they hunted birds, small mammals, deer, rabbits, and quail. It was also very common to have a milk cow or a goat. All of that was contaminated as the ash fell from the sky.

The source of water for people came from water–collecting cisterns. A cistern is normally an underground pit that was dug into the ground and then oftentimes plastered. During the rainy monsoon season, which we would have been in, water would be collected from people’s roofs and channeled into the systems. The ash that fell from the sky and then got to these roofs would then have been collected into a cistern. That contaminated water was then used for every purpose: drinking, bathing, cooking, cleaning, doing laundry.

A system for collection of water off the roof of a residence on the Black Hills Ranch, formerly the Nalda Ranch, east-northeast of the Trinity Site. The cistern to the left, which was damaged by the Trinity blast and then repaired, is still in use today. Source: Final Report of the Los Alamos Historical Document Retrieval and Assessment (LAHDRA) Project, Chapter 10

As ash fell from the sky, it got all over everything, as I said, including the animals. The government confiscated cows that were grazing in the area. Some of those cows had their hide burned off. I’ve had people tell me stories about how when they went to the cattle sale that year, everybody was astonished at how many cows were white, or half white, and how many cows had what they called eye cancer.

A number of people lived as close as 13 miles to the test site, and tens of thousands of people lived in a 50-mile radius. When the test was done, Colonel Stafford L. Warren, the Chief of the Medical Section of the Manhattan Project, wrote a letter to General Groves. General Groves was the man that was given full authority to conduct the Manhattan Project by the president, and he was adamant that this project was going to be pulled off in secrecy and the bomb was going to be tested, regardless of the harm that could be done to human health. The doctor [Warren] said afterwards a couple of really profound statements: “It is this officer’s opinion that this site is too small for a repetition of a similar test of this magnitude except under very special conditions. It is recommended that the site be expanded or a larger one, preferably with a radius of at least 150 miles.”7“Atomic Bomb: Decision — Trinity Test, July 16, 1945,” accessed October 25, 2020.

Later, Louis Hempelmann, the Health Group Leader of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, acknowledged in an interview, “A few people were probably overexposed, but they couldn’t prove it and we couldn’t prove it. So we just assumed we got away with it.”8“Opinion | When America Tested Nuclear Weapons on Itself – The New York Times,” accessed October 25, 2020.

Site Instrumentation: Camera Bunker At 10,000 West, Looking Southwest, White Sands Missile Range, Trinity Site, Vicinity of Routes 13 & 20, White Sands, Dona Ana County, NM. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/nm0139.photos.113961p/

If you draw a 150-mile radius around the Trinity Site, it encompasses Albuquerque to the north, El Paso and parts of Mexico to the south, past Silver City to the west, and past Artesia and Roswell to the east. It’s essentially our whole state. So the fallout actually damaged a very wide swath of the countryside. When the cloud went up, it got divided into different sections, depending on where it was in altitude and what was happening with the wind patterns at those different altitudes. So it spread all over in different forms, but they followed the main part of the plume all the way to the Atlantic Ocean.

Not surprisingly, there has been no abatement to the damage that was done. Without a doubt, there is still plutonium with a half-life of 24,000 years in the desert in New Mexico. What is also so sad about this history is the government’s egregious lack of concern for human health. They even allowed people to go in and out of the Trinity Site until they closed it, during the sixties, I believe. Before that, people would take children out there on field trips.9Trinity site remained closed to the public until 1953. Today, it can only be visited twice a year, the first Saturday in April and October.

The consequences of this event also had a big impact on my own family. My dad died after having three different cancers that he didn’t have risk factors for. After my father passed away, my dad’s oldest brother called me up and told me about their life when they were kids. He said that my father used to drink a lot of cow’s milk. They would go in search of cow’s milk for my dad on a daily basis. According to my uncle, my father didn’t drink glasses of milk, he drank gallons. Since my grandmother didn’t have a cow, they would get milk from local dairies.

It is well known that milk is one of the most significant pathways that people get radiation exposure from. A health physicist once told me that the radiation settles in all the glands of your neck. My dad got oral cancer and he wasn’t a smoker, he wasn’t a drinker, he didn’t have viruses. Then he had cancer at the back of his tongue and then at the front of his tongue, two distinctly different cancers that weren’t metastatic. The second one is eight years after the first one. My uncle told me that he remembers that my grandmother would take them to the Trinity Site on picnics, and according to my uncle, everybody did that. I’ve heard from many sources that people would go out there and packed their pockets “of that green glass,” trinitite, and they brought it home. It was something unique; you played with it. It was like, we had a collection of marbles and this was just something else we could add to our collection.

The way the government handled the access to the Trinity Site afterwards, to me, is unconscionable. They allowed people to go out there freely knowing that it was not safe. But there was this push, and I know about it because I grew up inside of it, of our government to influence all these local communities into believing that they had participated in something very significant and they needed to take pride. Part of it was also associated with the fact that many people worked at Holloman Air Force Base and White Sands Missile Range. You don’t bite the hand that feeds you.

I spoke to some Hispanic men about a year and a half ago; one of them is gone now, because he was literally dying at the time of the interview. He and his colleagues told me the stories about how they used to work on a film crew out there after the Trinity test, filming all the explosions that they conducted out there subsequently. These weren’t nuclear explosions, but some of them were more powerful than the Trinity test, and they said that it literally created a crater that was 10 to 12 stories deep, and they sprung water. That’s also part of the history of this, because that basin was so contaminated that every time they would detonate something it would disperse particulate matter into the environment again. It was, again, in the air we would breathe; it would come over our homes again and become part of our adjacent environment again and again and again.

What was profound to me about speaking to them is that the company that they worked for, which before going out of business robbed their retirement accounts, made them sign releases saying that they would never discuss any of this with anybody. These men fully believed that even though this took place so long ago and the company they worked for didn’t exist anymore, they couldn’t talk about it. “We swore to secrecy,” they said. So what happens is they instill in you this idea that you have to take pride in all these things. This contributed greatly to the fact that people didn’t speak up about what they were going through.

AGL: After the population started to learn more about the explosion and its radiation, was there any change in how people lived or ate? Did the most-affected populations ever consider leaving the area?

TC: People had to be able to feed themselves, take care of themselves, and make a living. So those people who farmed and ranched continued to do those things. Some people were kicked off their land to establish the Manhattan Project, and afterwards many ranchers were displaced because they realized that the land was so damaged. [The government] knew it wasn’t safe for people to continue to live 13 miles away, but people continued to do what they always did, and part of it is because people didn’t understand what radiation exposure meant.

There’s a story about a rancher that lived very close to the Trinity Site; I think his last name was Raitliff. The government had tried to map out all the ranchos in the vicinity in order to know where everybody was and they could check on them afterwards. But they discovered this one family after the explosion. I think that they lived about 13 miles from the Trinity Site. So one day, they showed up in some protective gear at Raitliff‘s ranch with Geiger counters. Mr. Raitliff asked, “What are you all doing here?” and they said, “We are checking for radiation.” Mr. Raitliff replied, “You won’t find it here, because we don’t own a radio.”

Some people laugh when I tell that story, and it is fairly funny when you think about it. But the government depended on the fact that people were unable to understand the process and stick up for themselves in this huge mess. The idea of radiation exposure didn’t really become people’s realities for many, many years.

Most people tell me now that the government will never come back to acknowledge what happened. “Why would they come back? They got away with it and they haven’t come back in all these years,” they tell me. So I don’t think people have changed their lifestyles very much around this. But people are very much aware of it. I mean, I still know people who garden in Tularosa and who have orchards. Some of those orchards are over 100 years old. Lots of people have fruit trees that are really old in Tularosa. I’ll be honest with you, I still make jams and canned fruit and vegetables. I don’t necessarily get them from there, but what I can tell you is that it is hard to just disconnect yourself from your culture.

I’ve had people ask me, “Why don’t you guys just move away?” That is so interestingly naïve, because people become very rooted in place, especially Hispanic and Native people. The church in Tularosa is 150 years old. The settlers that came up from Mexico found this place that had its own water running through the creek and they built the largest ditch system that exists in New Mexico. They established these 49 blocks with ditch access. There was a ditch blowing in front of our home that we used to water our orchard and garden.

So for people to think that it's just so easy to take yourself out of a place that you are so rooted to . . . It just doesn't happen. Furthermore, people didn't have the resources to just pick up and go. Where do you pick up and go to?

One time, when my mom was in the middle of an interview, she said, “If you think that my husband and I would have raised our children in a nuclear wasteland, you are completely wrong.” She continued, “If we had known and understood what had happened to our environment, we would have done everything to gather up resources to move away, as hard as that would have been. Because we loved our families.” So even though the government admitted that it was a radioactive-producing bomb, people didn’t know what that meant. They had no clue. They had no clue how to take care of themselves, because nobody ever talked to them about taking some minimal precautions.

A couple of summers ago I met a woman, probably in her nineties, that lives on a ranch near Carrizozo. She still uses a cistern for water, and she told me, “I fully know the reason I lost all my relatives is that we were exposed to radiation.” I firmly believe that if I could find the resources, go back and open up some of these cisterns, we would find plutonium still existing inside.

I remember the first time I went back to Tularosa and did the presentation that I do now. I looked to the room and saw mothers, fathers, sisters, and brothers to people I grew up within my community. I’m telling them this story, and I can just see the look in their eyes that they’re getting it. That explains everything about why everybody they know is sick and dying. It explains why in our communities, instead of wondering if we are going to get cancer, we wonder when we are going to get it, because everybody has had it.

People in New Mexico turn hardship into kinship. We learned how to take a very hard life and make it work, and so it’s not that we’re averse to that. It’s just that this whole invasion of our environment, and the destruction of our environment, has made that process much harder for us. If it wasn’t for the faith that people have, I don’t know how we would have been able to sustain ourselves.

AGL: Yes, especially with all the data and oral histories that prove the massive effects of this horrendous event. Can you talk a little bit about the mission of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium and the work that you’ve been doing with them since 2005?

TC: Originally, we just wanted to hold the government accountable. We wanted the government to come back, apologize to the people, and acknowledge that we were enlisted into the service of our country without knowledge or consent. But we then found out that there was a fund set up in 1990 called the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) to offer compensation to downwinders of the Nevada test site, and we were devastated. I truly couldn’t believe that the story could get worse. But for me it became very much worse when I found that out, because I thought: “How in the world have they been taking care of other people?” We were relegated to nothingness, counted for zero in that equation. So we have been working ever since in documenting as much of the history as we can, because people are dying all the time. We have documented oral histories, cancer cases . . . Meanwhile, the government has never come back to do that. A full epidemiological study should have been done many, many, years ago: 10 years after the explosion, 20 years after the explosion. But since none of that has been done, we developed a health survey, and we have collected thousands of these health surveys. We are trying to build a case for why we should be included in the RECA.10Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium and M. Gómez, Unknowing, Unwilling, and Uncompensated: The Effects of the Trinity Test on New Mexicans and the Potential Benefits of Radiation Compensation Act (RECA) Amendments (Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, 2017).

A number of researchers are still looking at the aftermath of the explosion. I have collaborated with a scientist, Dr. Joseph Shonka, who is a nuclear engineer and a health physicist. He worked in the CDC’s Los Alamos Historical Document Retrieval and Assessment (LAHDRA) Project, and he has extrapolated some information based on the LAHDRA report and the work of other scientists on this matter.11Widner and Shonka. One of his findings relates to exposure. He has been able to show that the people from New Mexico were exposed to 100 times more radiation than the Nevada Downwinders. And that’s profound, because it has never been acknowledged by the government. We have never been given any kind of assistance in dealing with this. The other thing that we learned this summer, which is very important, is that after they took the testing to Nevada, they put monitors in place all over the Southwest, including New Mexico. These monitors showed that we consistently received radiation doses from the Nevada test site through the summer of 1962.

Exposure to radiation is cumulative. The way it has been described to me by experts is that we received this very high dose from Trinity, and then we would consistently receive cycles of lower doses from the Nevada test site. If you look at a map of where people are compensated and where they are not through RECA, the compensation ends right at the New Mexico–Arizona border. So if you lived five feet into Arizona and developed cancer, you were compensated and taken care of. If you lived within five feet into New Mexico, you were not. [But] it’s not like there’s a lead curtain that exists right there, protecting us somehow.

That is absolutely not acceptable. Our work is about educating people, making sure everybody understands that while the government said for 75 years that the area around Trinity was remote and uninhabited, that is not true. Educating people about the fact that tens of thousands of people live adjacent to the Trinity Site, within a 50-mile radius. I truly believe that we can no longer allow our government to look the other way.

AGL: What would it take to be incorporated in the RECA amendment? And how can people reading this interview support this effort?

TC: There has to be political will. I believe that political will is sometimes driven by a movement, and there is always a tipping point with every movement. I truly believe that we are getting closer to that tipping point; I can feel the difference now. Over the last ten years, two bills have been introduced, one in the House, H.R.3783, and one in the Senate, S.947, to add us to RECA. The very sad thing is that they’ve been entered for ten years now, and all we’ve ever received is two hearings in the Senate, and never has there been a vote, which is totally unacceptable. We are now up against a deadline. The bill will sunset in 2022, and if these bills are not passed, or if that sunset clause is not extended, the heavy lift that we’ve been pushing for 15 years will become almost an impossibility.

Everybody that wants to support us needs to do outreach to their particular congressional delegates and ask them to support H.R.3783 and S.947 bills to add the Downwinders of New Mexico to the compensation.12Report From Santa Fe, Produced by KENW | Tina Cordova | Season 2020 | Episode 22, accessed October 25, 2020.

Our work is about education and documenting cancer history so that when we get the amendments passed we can reach out to people and suggest that they apply. It is also about making sure that people understand that there is hope and that we will continue this fight. I say this regularly: “I will continue doing this work until the time that the government is held accountable and does the right thing, or the time that they put me in the ground.”

I have done a lot of other things in my life that have prepared me to do this work. I was a huge advocate on the highest levels for minority-owned businesses and women-owned businesses. I was the chair of the board of the United States Hispanic Chamber of Commerce and the legislative chair for five years. Back then, I interacted with government officials at the highest level, including the President of the United States at the time. I learned all about advocacy, and it prepared me to do this work. I really do believe that I was meant to do this work.

AGL: What do you think that the compensation could mean for New Mexico and your community in Tularosa?

TC: What happens now is that people end up spending all they have to take care of their health. When you are diagnosed with cancer in Carrizozo, Socorro, San Antonio, or Tularosa, you are not diagnosed where you live, and you are not treated where you live, because there are no medical facilities. You have to travel, and sometimes you travel great distances.

I know a family from Tularosa—it is hard for me to actually think about it, but there was this wonderful, beautiful woman from Tularosa, and she got leukemia. When they told her in El Paso that there was nothing else they could do for her, her family decided to take her to MD Anderson in Houston, Texas. Her husband and she didn’t have a lot of resources, although luckily she had health insurance. So her husband hooked up their camper trailer, drove to Houston, parked it in a campground, left her there, and drove back to Tularosa to go to work. That was the only way they could pay their electric bill. So she remained there by herself; her children would take turns and spend a few days with her while she was going to treatment. She had to make her way from the campground to MD Anderson by herself. She had to go through the agonizing uncertainty by herself. She ended up dying. I always think about what that must have been for her. It is just so hard for me to think about it.

So what happens with people in New Mexico is that we spend all we have to take care of our health. People end up taking out all the equity in their house, maxing out credit cards, borrowing money everyplace they can find it. Then we don’t get to develop generational wealth that might help a child go to college or buy a home. If all of a sudden there was this infusion of resources that allowed you to take care of health and not go into this deep debt, it would transform our lives, and the ones of future generations. When there is this infusion of money that is in that level and scope, it actually creates its own economy.

We know that with RECA lots of people could apply on behalf of a deceased loved one and receive compensation. Their family members are gone now, and there’s nothing that can ever fully compensate you for losing somebody, but at least it would give some of these families an opportunity to maybe change the course of what happened financially to them.

We were enlisted in service and we have given all we have. We bury our loved ones on a regular basis, and I don’t know what else they want, or can take from us. So that’s why this has become my life’s work.

Biographies

is the cofounder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium (TBDC). She is a sixth-generation native New Mexican, born and raised in the small town of Tularosa in south central New Mexico. In 2005, Cordova cofounded TBDC with the late Fred Tyler. Its mission is to bring attention to the negative health effects suffered by the unknowing, unwilling, uncompensated, innocent victims of the first nuclear blast on earth that took place at the Trinity Site in south central New Mexico. Cordova is a cancer survivor, having been diagnosed with thyroid cancer when she was 39 years old.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.