River Valley, Maine

Mill Supply: Making Paper and Maintaining the Technological Sublime

In this two-part feature on Work & Economy, report editor Aaron Cayer and artist Tom Leytham describe the history of industrial mill work and its consequences on the landscape, the community, and the politics of the town.

Part I features Cayer’s essay, “Mill Supply: Making Paper and Maintaining the Technological Sublime,” which examines the architectural history of the Rumford paper mill, once the largest producer of book paper in the world, and the ways in which its “sublime disciplining power” have been maintained and reproduced by books, films, reports, and media. He reveals how this maintenance was and continues to be made possible by a sustained practice of “glossing over” of mill supply. Just as the paper was coated to conceal variation, the concerns of papermakers who offered their labor, and in many cases their lives, were ignored. The gloss remains, and the lure and disciplining power of the mill continue to define the community through new mediums. What might a post-mill future look like, and how might it feel? —Maine’s River Valley report editors

Read part II of the Work & Economy feature here.

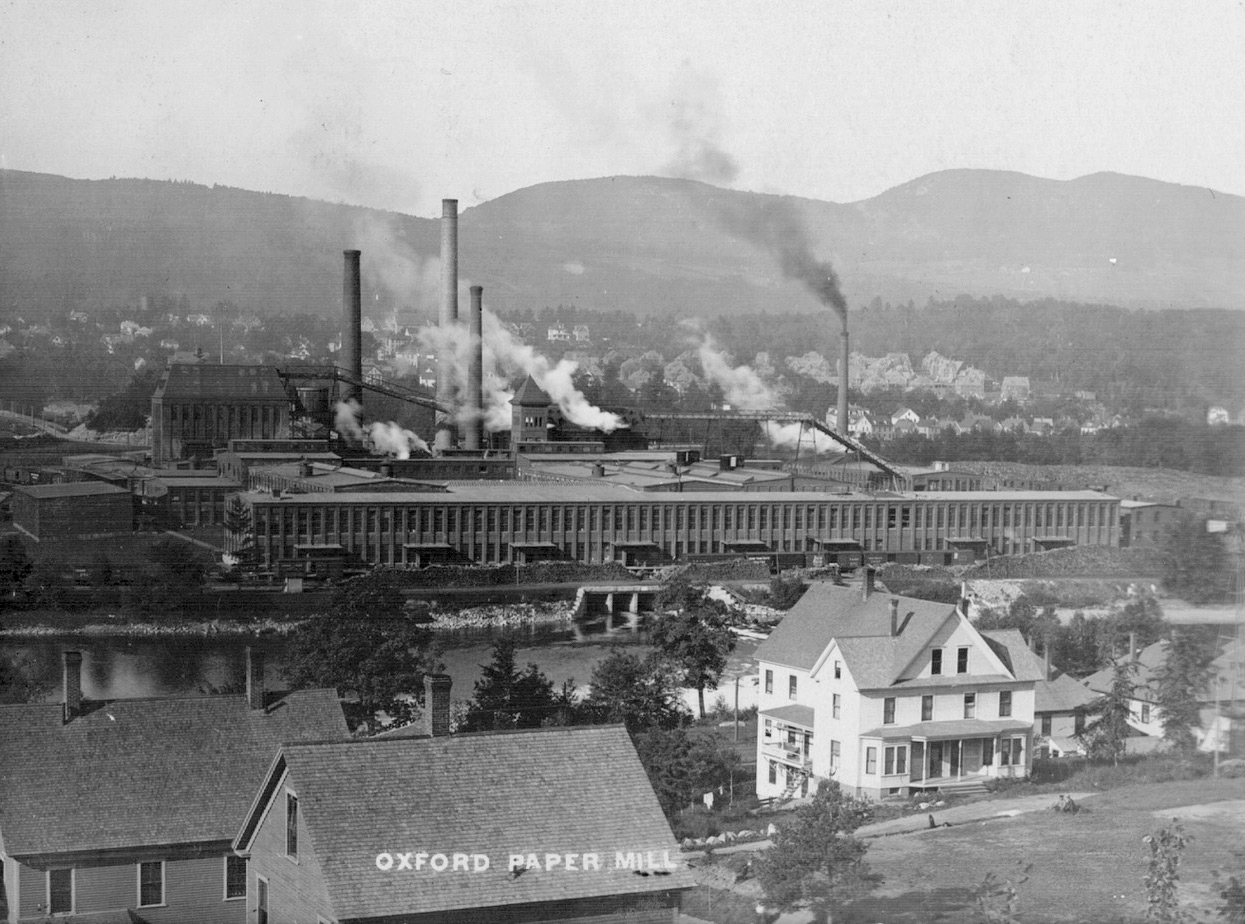

Pulp and paper mills were and continue to be integral parts of New England landscapes, though the labor power and the natural resources that feed them are overshadowed by the spectacles of their production: their tall, polluting smokestacks; their hissing steam vents, clanking cranes, and bulldozers; their sour sulfur stench; the rationalism of their machines and the imposing brick walls that enclose them. The Oxford Paper Company, constructed in Rumford, Maine, in 1901 at the direction of Canadian-American industrialist Hugh J. Chisholm, serves as a fitting example of what historian David Nye has described as the “American technological sublime”—a modern industrial technology that elicited the same reactions of wonder, awe, and terror as those prompted by nature.1Nye, American Technological Sublime. As papermakers, community members, and tourists alike championed the unprecedented size, volumes, and speeds associated with mass paper production, the mill became a fact of the River Valley landscape that continues to impress discipline and identity upon all aspects of the community. While the dominant thrust of capitalist production has radically shifted over the course of the twentieth century, from the production of industrial goods at the turn of the century to the production of experiences by the century’s end, this article reveals how the technological sublime has, over the past several decades, maintained and reproduced itself through the production of consumable experiences of workers in the mill, rather than merely through the production of paper. I argue that this technological sublime is maintained today by a long and continuing practice of “glossing over” of mill supply in its most particular: looking past and denying views of the textured and pungent wood that feed the mill, as well as the health and wellbeing of the worn-down papermakers who offer their labor power and, in many cases, their lives.

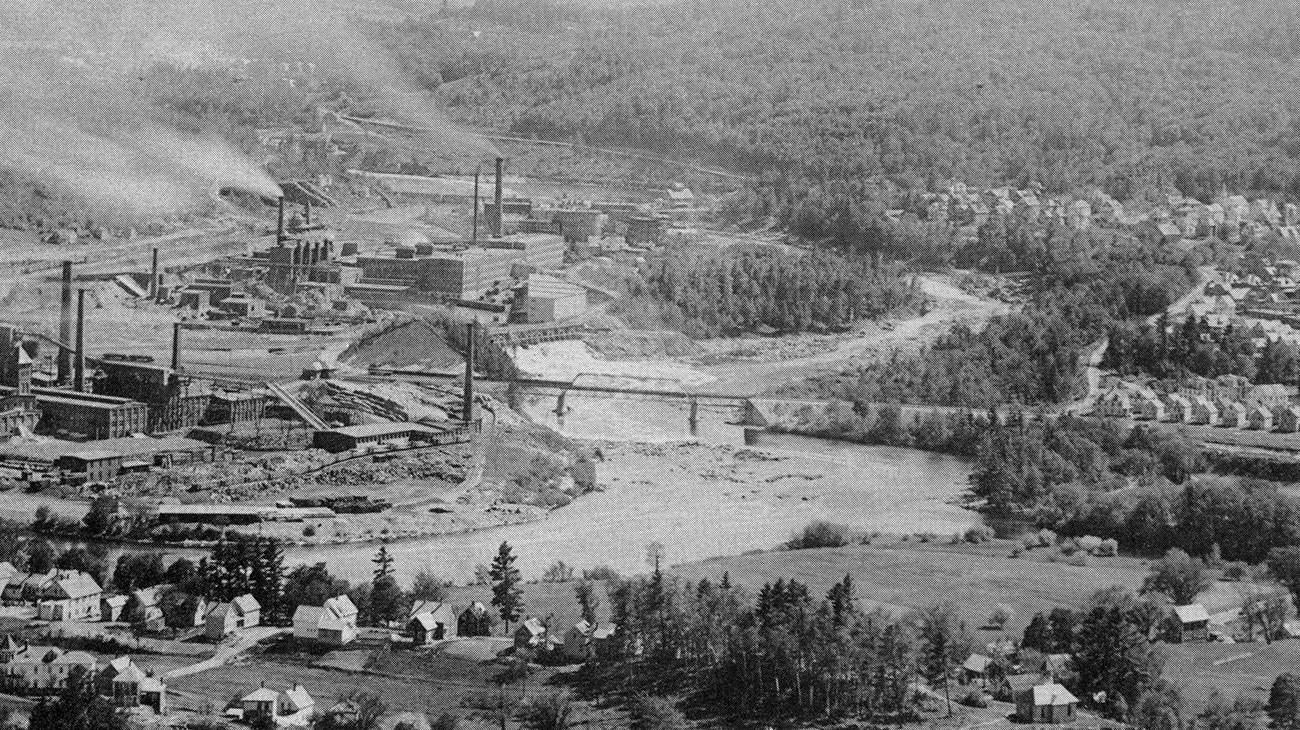

The mill was built within the western foothills of Maine due to the seemingly limitless supply of natural resources for the production of paper. Loggers cut wood from the vast forestlands, and the fast-flowing river with its impressive waterfall powered the mill and helped to circulate and treat the wood. Like elsewhere in New England, the paper industry transformed Rumford’s agricultural community into a pastoral industrial center—one that had less than 900 residents in 1890 and nearly 11,000 in 1940.2The Rumford Comprehensive Plan Committee, “Rumford Comprehensive Plan.”

Within its first five years of operation, the Oxford Paper Company was the sole manufacturer of postcards for the US Postal Service, producing three million cards per day with its four paper machines. By the 1930s, the mill had become known for its specialty and coated papers for books and magazines, and it was the largest producer of book paper in the world under one roof, with a capacity of 350 tons of paper per year.3Burns, Gawtry, and Ha, “For the Love of Paper.” By the end of the twentieth century, the company’s gloss-coated paper was used for magazines such as National Geographic, Vogue, Sports Illustrated, Reader’s Digest, and later O Magazine; by book publishers such as Macmillan; and for envelopes and coated labels for water bottles and soup cans.

This glossing over of the wood, which through chemical treatment obscured variation in texture, density, age, and color in order to produce the smoothest, whitest surface, was not unlike the glossing over of the catastrophic environmental and health impacts experienced by the mill’s laborers. While the water and wood supply has more or less stayed steady over the past 118 years as the number of machines and laborers has decreased, shifts in the nature of economic production have radically transformed the commodifiable outputs of the mill and continue to demonstrate that, despite decades of air and river pollution, labor precarity, exploitation, and loss of life that has helped the sour-smelling region earn the title “Cancer Valley,” the force of the technological sublime is upheld and reproduced—not because the discipline and power is inscribed in the very permanence of the mill’s architecture, but because the experience of the sublime has been recorded, circulated, and commodified on the very paper that the mill produces, and which may live longer than the mill itself.

In 2018, the Rumford mill was purchased by Chinese paper company Nine Dragons. It is telling that the company celebrated the experience of the mill’s local workers, rather than the mill’s volume of production, in its 2019 annual report, confirming the mill’s shift from an industrial to postindustrial actor: “The Group’s specialty papers are inventive and adaptable, with consistent quality, superior customer service and reliability … the Group’s Rumford Division has over 20 years of experience selling into these markets.”4Nine Dragons, “Annual Report 2019/2020.”

By the 2000s, while the company was still committed to the production of paper, it no longer supplied merely the paper to publishing companies and printers—it also offered the content to be printed on its very pages. To extend Marshall McLuhan’s line, the mill contributed both medium and message.5McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 7-21. Just as Nine Dragons boasted about the experience of local workers to its shareholders, mill workers and their families—their experiences—had become the subjects of best-selling books, articles, and documentaries—of their losses, grief, and reconciliation with mill town life.

These include Maine native and novelist Monica Wood’s 2012 book When We Were the Kennedys, which depicts her experiences growing up in the working-class town of Mexico—the sister town to Rumford—including the loss of her father, who worked in the mill, and her family’s struggle to outline a path forward.6Wood, When We Were the Kennedys. She describes the mill as an omnipotent, God-like structure with the power to both give and take as it pleased. Her best-selling book was featured in O, The Oprah Magazine and adapted into a play, Papermaker.7Bolton-Fasman, “7 Tales.”

Another example: Former Rumford-based writer Tom Fallon worked, read, and wrote while on the job in the Rumford paper mill, and claimed to produce the “only twentieth-century Maine paper mill short stories based on experience,” including his “Holding” and Uncensored Paper Mill.8Fallon, “Holding,” 160-173.

In 2010, Smithsonian documentary film The Rivals highlighted class struggle by celebrating the learned lessons of “discipline” and “victory” through stories of competing football teams: one from the blue-collar mill town of Rumford and the other from white-collar Cape Elizabeth—a town with “so much money and drive that they are already threatening Mountain Valley’s [Rumford] dynasty.”9Wolfinger, The Rivals.

And finally, Mexico native Kerri Arsenault (and co-editor of this report) begins to challenge the mill’s subliminality in her 2020 Mill Town: Reckoning With What Remains, in which she describes her upbringing in the town and her continued, yet circuitous search for answers in the face of silenced community advocates. In the book, she searches for explanations for the catastrophic environmental offenses caused by the mill that have been and continue to be glossed over; for the statistically higher rates of cancer in the region that are repeatedly dismissed or proven “inconclusive”; and for the ways in which ambiguity defines the lives of the townspeople when the mill is threatened.10Arsenault, Mill Town: A Reckoning with What Remains. In her book, published by St. Martin’s Publishing Group, Macmillan Publishers, Arsenault writes that the text is printed on paper bleached without chlorine gas, chlorine dioxide, or any other chlorine-based bleaching agent.

The attention to the industrial volumes of production and the awe-inspiring scale of the mill has, like the coating added to the paper that is made inside the mill’s walls, forced a historical glossing-over of workers’ struggles, their efforts to resist, and the destruction of the idyllic landscape and waterways for which the region was once known—all in the name of smooth and seamless lines of production, an ideal form of order, and capital returns. I suggest that these new experiential products of the mill are fundamentally tied to the parallel histories of postindustrialization and the rise of an economy that values commodifiable experiences over lived realities. While the medium of the technological sublime has been modified, the message of the mill’s power is maintained.

Prior to the mid-nineteenth century, paper was produced primarily by extracting fibers from recycled cloth rags; however, during the middle of the nineteenth century, America’s rapid industrialization presented a demand for paper that could not be met by the supply of rags alone. Investors turned to wood, and mills were constructed throughout New England. The western foothills region of Maine was home to the idyllic and meandering Androscoggin River. In the town of Rumford, the river plunged over a ledge of nearly 176 vertical feet which has been described as a “little Niagara” or “the grandest cataract in New England.”11George J. Varney, A Gazetteer of the State of Maine (Boston: B. B. Russell, 1881), p. 483. The Anasagunticook people of the Abenaki tribe once gathered to fish in the large thirteen-acre pool below the falls, where they traded furs from the lakes region of Maine and valued fresh spring water that flowed in tune with phases of the moon.12Bennett, The Mount Zircon Moon Tide Spring: An Illustrated History. By the nineteenth century, small sawmills and gristmills populated the river’s edge, though the economy remained agricultural until the 1880s.

In 1882, Hugh J. Chisholm viewed the waterfall and the pastoral landscape as prime for the production of paper, and he acquired 1,200 acres of land from private landowners. As equal parts industrialist and businessman, he purchased controlling stock in and directed the construction of the Portland and Rumford Falls Railway, which connected Rumford to a national rail network. He established the Rumford Falls Power Company in 1890 and the Rumford Falls Paper Company in 1891; by 1906, he had formed both the International Paper Company and the Oxford Paper Company.13In 1898, Hugh J. Chisholm formed International Paper, which combined twenty different pulp and paper mills in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Northern New York. Oxford Paper Company, presently named ND Paper, continues to dominate Rumford’s economy.14The Oxford Paper Company was purchased by the Ethyl Corporation in 1967; the Boise Cascade Paper Company in 1976; the Mead Corporation in 1996, NewPage in 2005; Catalyst Paper in 2015, and Nine Dragons in 2019.

Oxford was strategically situated at the base of the Rumford (Penacook) Falls, deep within a valley of surrounding mountains, and the river split and defined much of the mill’s perimeter (see image above). The mill was designed by Holyoke, Massachusetts-based architect and engineer Ashley B. Tower, who worked with and later succeeded his brother at their firm D.H. & A.B. Tower, Architects and Civil and Mechanical Engineers.15Toomey, et. al, Massachusetts of Today: A Memorial of the State, 404. After apprenticing as a builder for three years and then studying business, Tower was elected city engineer in 1881 before joining his brother in 1878. By the end of the twentieth century, the firm was the largest designer of paper mills in the country, with mills and factories constructed in states from Maine to California, and in countries including Canada, Mexico, Germany, Brazil, India, Japan, and Australia.16Toomey, et. al, Massachusetts of Today: A Memorial of the State, 404. By the 1890s, the firm listed mills in the US as: the Kimberly and Clark mills at Kimberly, Wisconsin, the Telulah Mill in Appleton, Wisconsin, the Glens Falls Paper Mill at Fort Edward, NY, the Ticonderoga Mill in Ticonderoga, NY, Denver Paper Mills in Denver, CO, the Shattuck and Babcock Paper Pill at De Pere, Wisconsin, the Linden Paper Mill and the Riverside Paper Mills in Holyoke, MA, and the Niagara Falls Paper Company Mills at Niagara Falls, NY. The firm’s 1887 design of the Fábrica de Papel de Salto, owned by the company Melchert & Cia, in São Paulo, Brazil was situated on the banks of the Tietê River and powered by hydroelectric energy. The mill was one of the earliest industrial paper mills in South America and it continues to produce specialty paper as well as paper for money. See: Brazilian Pulp and Paper Association, “The History of Paper in Brazil,” 2007. The firm focused on the ways in which landscapes with especially difficult terrain and powerful rivers with waterfalls—features that historically defined sublime landscapes—could inform the architecture and power the mills. No two mills were designed or built alike, the brothers argued, due to the uniqueness of site constraints, as well as the volumes of production that varied by request.17Warner, Picturesque Hamden Part 1- East, 133.

But beyond hundreds of paper mills peppering the globe, the Towers also designed civic structures, including penitentiary systems such as the Hampden County Jail and House of Correction in Springfield, Massachusetts, which was built in 1886. While the mills and the jails differed programmatically and geographically, they both represented institutions predicated on discipline.

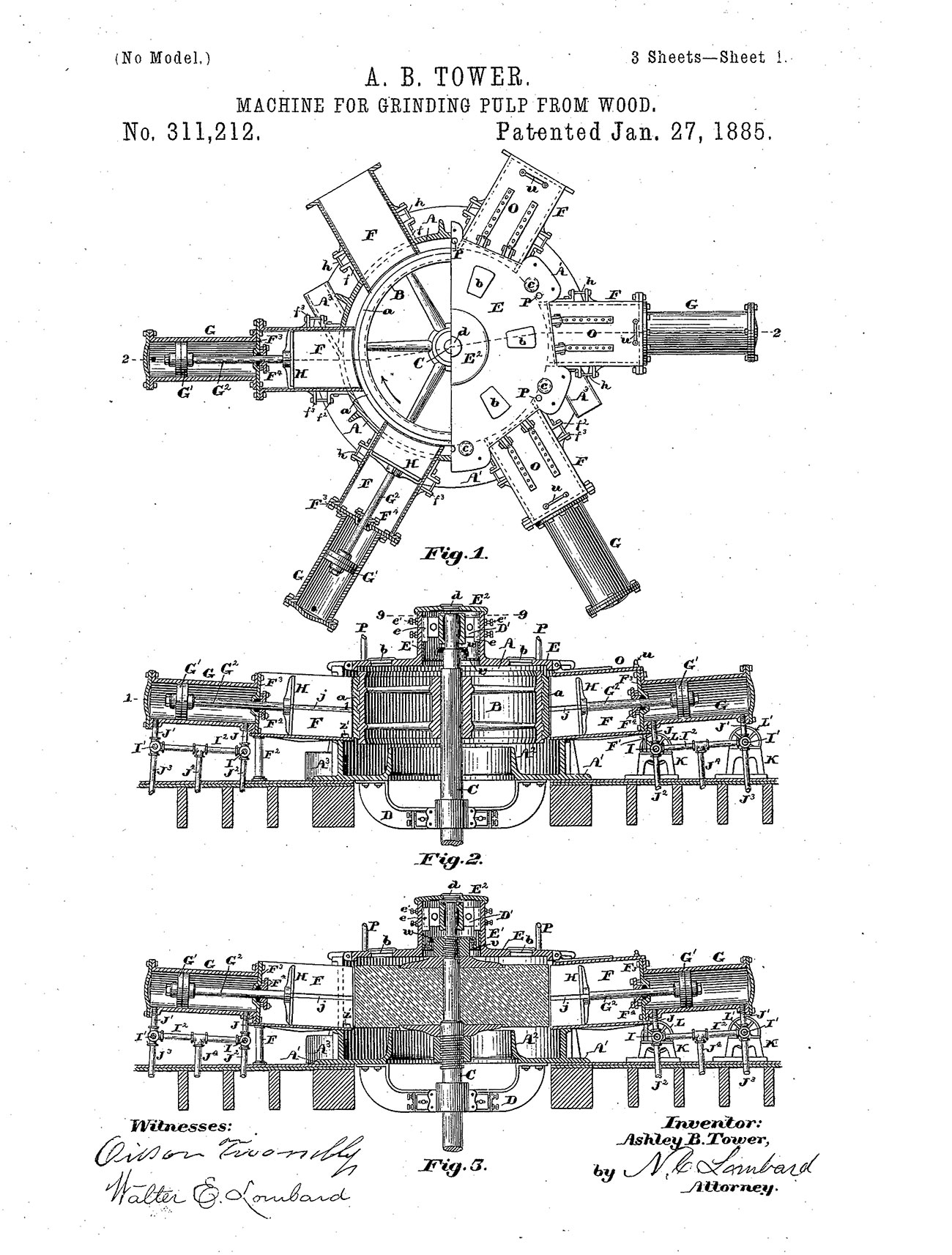

By the 1880s, Ashley Tower had become famous as an inventor. His patented machines were dedicated to improving the paper production process in order to maximize output and minimize labor input, and thus the landscape, the machine, and the architecture were designed at once. In 1885, he was granted a patent for a machine that ground pulp from wood; in 1899, for a driving connection for paper machinery.

In his patent application for the pulp grinder, he wrote: “My invention relates to that class of machines for producing wood pulp, in which a series of wood-holding chambers or hoppers are arranged around a common grinding-wheel mounted upon and revolving about a vertical axis; and it consists in certain novel constructions, arrangements, and combinations of devices…”18A. B. Tower. Machine for Grinding Pulp from Wood. US Patent 311,212, issued January 27, 1885. The machine received wood through feed-boxes or hoppers that fed the central grinding wheel, and the pulp was deposited at the bottom of the central cylinder as it was ground (see image below).

Ashley B. Tower, Plan and Section of a “Machine for Grinding Pulp from Wood,” 1885. Image courtesy of Aaron Cayer

While the machine provides a historical metaphor for the wearing-down of workers that continues to be used by community members to describe the paper mill—“the grind”—it also represents a mechanism of discipline that scales up from machine to mill, and from mill to town. The machine served to grind the wood by stone, to draw it inward through troughs into a centralized chamber, and to pulverize the wood into uniform pieces ready for the treatment phase of the papermaking process. Like the machine, the mill itself functioned as a mechanism through which workers were organized, disciplined, and marshalled into order to ensure that the paper machines ran efficiently.

The plan of Tower’s grinding machine also served as a diagram for the kind of discipline embedded in the architecture of the mill. The drawing reveals a design not unlike Jeremy Bentham’s 18th-century Panopticon, later theorized by Michel Foucault as the ultimate realization of a modern disciplining institution, and thus it may be no surprise that the Towers were designing a prison just as they were designing a paper mill.

Left: Elwood Kidder working at the chip conveyer, Oxford Paper Company, n.d.; Right: Machine workers at the Oxford Paper Company, n.d. No shoes were worn, since leather soles were often more slippery on the machine floor than bare feet. Credit: Rumford Historical Society. Images courtesy of Aaron Cayer

The Rumford mill opened in 1901, and by 1902 there were four paper machines producing 44 tons of paper per day.19Burns, Gawtry, and Ha, “For the Love of Paper.” Chisholm lured workers to Maine by offering above-average wages, housing, and retirement benefits, though they were still largely stratified by salary and immigrant status: salary vs. hourly, immigrant worker vs. non-immigrant, skilled vs. unskilled.

By 1904, Chisholm had formed a Rumford realty company and developed over 250 dwelling units for workers. The social hierarchies of the mill informed the layout of the hillside community. Larger homes for mill managers and owners were located on Franklin Street, near the top of the hill. Middle management and most salary workers lived midway down in an early planned worker-housing community, the Strathglass Park, designed by New York architect Cass Gilbert between 1901 and 1902. While mill owners, managers, and salaried workers owned their homes, multi-story rental homes and apartments for many hourly workers were located at the bottom of the hill closest to the river and train tracks, an area known as the “Flats” (see first image).20Leane, The Oxford Story, 16.

In addition to housing, Chisholm invested in a community recreation center known as the Mechanics Institute (presently the Greater Rumford Community Center), along with schools, hospitals, and churches for the mill workers, in accordance with the logic of other all-encompassing industrial towns. He referred to the town as a “City in the Wilderness.”

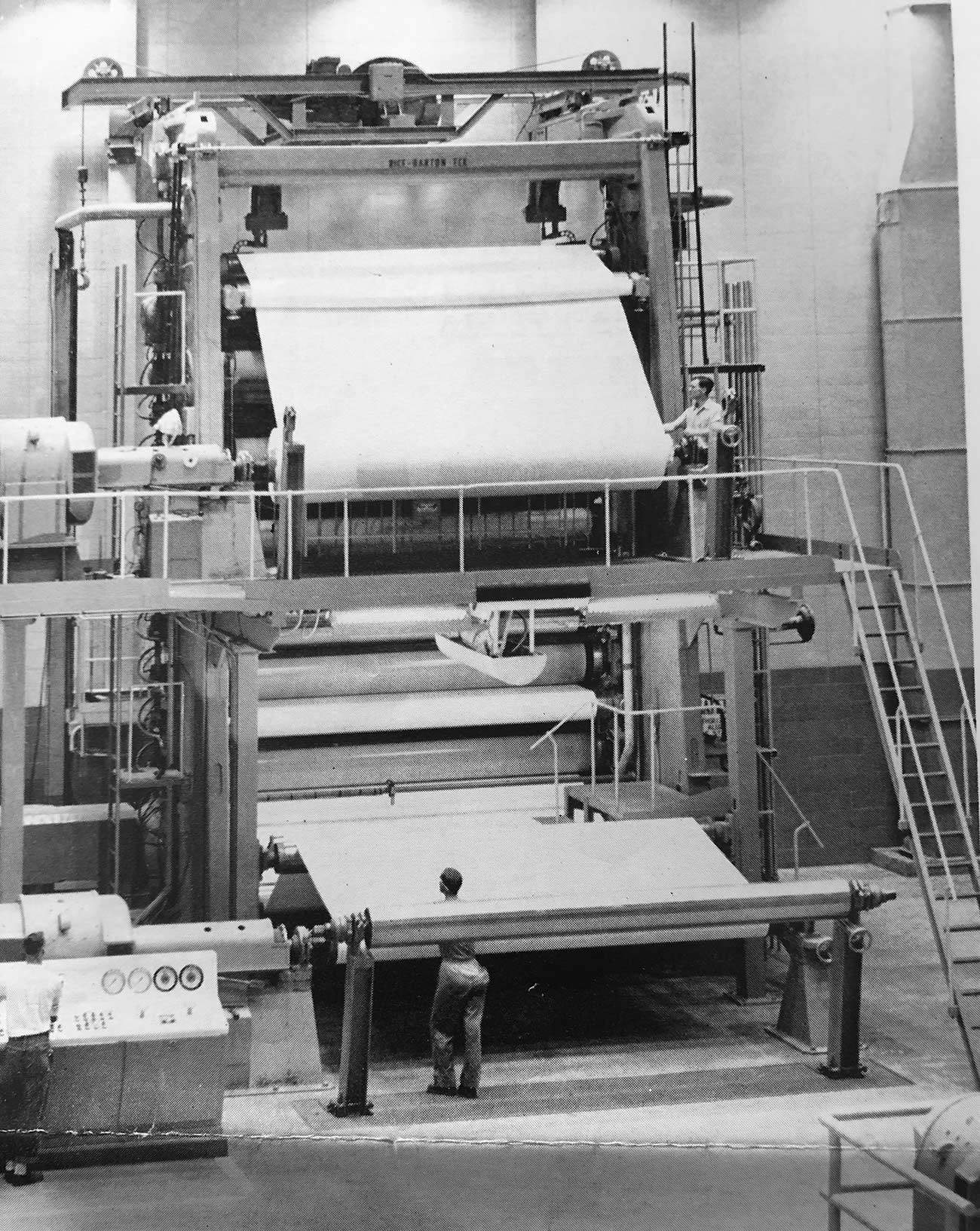

In 1912, Chisholm stepped down as president of Oxford, and his son, also Hugh Chisholm, who had studied the arts at Yale and law at Harvard, oversaw the mill’s next phase of development. The younger Chisholm was committed to expanding the mill, and he determined, through in-house market studies and consumer research, that it could become a leading producer of high-quality book and specialty papers. At the same time, he observed a growing demand for high-gloss papers, and the Maine Coated Paper Company was established in 1913 with six single coating machines. Initially, the Maine Coated Paper company purchased paper from the Oxford Paper Company to coat, cut, package and ship, and it expanded to twelve coaters by the 1930s. However, in 1922, Oxford acquired the company and consolidated the efforts.21Burns, Gawtry, and Ha, “For the Love of Paper.”

ECK Supercalender for North Star Coated papers, Oxford Paper Company, 1959. Credit: Rumford Historical Society. Image courtesy of Aaron Cayer

The Technological Sublime

Historian David Nye has argued that mills dotting the pastoral landscapes of New England were impressive, though their subliminality was less a result of the architecture and more the outcome of their massive volumes of production and mechanistic disciplining of workers who were marshaled into an “ideal order”—a form of order that extended outward and defined all aspects of the town.22Drawing on Irvin Goffman’s concept of a “total institution,” the order applies not only to the mill, but the entire town as a social system, including churches, housing, schools, leisure spaces, and moral supervision of the workers. By subjecting the workers and their families to the rationality of production that characterized pulp grinding and millwork, the company could, in its earliest days, control nearly every aspect of its workers’ lives. Nye argued:

The industrial sublime combined the abstraction of man-made landscape with the dynamism of moving machinery and powerful forces. The factory district, typically viewed from a high place or from a moving train, thus combined the dynamic and geometrical sublimes. The synthesis evoked fear tinged with wonder. It threatened the individual with its sheer scale, its noise, its complexity, and the superhuman power of the forces at work … these landscapes forced onlookers to respect the power of the corporation and the intelligence of its engineers.23Nye, American Technological Sublime,126.

Drawing on the works of Immanuel Kant and Edmund Burke, Nye suggests that the emergence of pastoral mills in the US offered a new relationship to seeing, and the mill was understood as a particularly American industrial spectacle. The mill slipped into the logic of tourism as a fact of nature—a fundamental part of the landscape—because of its designed subliminality: its power, vastness, obscurity, and complexity that, not unlike the thunderous waterfall, could inspire awe. Paintings, photographs, and depictions of the mills and the mill yard looked past the rawness and the messiness of the sites from high above. Imagined at the turn of the twentieth century, they dehumanized and looked past the workers in order to bolster the economic triumphs of the Gilded Age.

An 1890 watercolor of the planned paper mill and community was used as a promotional and planning tool in the development of Rumford. Its qualities resemble those described by Nye, as well as those imagined by Ashley Tower. The sweeping aerial view is enhanced by a long and exaggerated perspective that produces a flattening effect on the otherwise tall and imposing mountains surrounding the valley. The river is a vibrant blue and the mill is painted in a soft pink tone that forces a compromise between nature and architecture, since its hue reflects an agreeable middle ground between the deep red brick mill buildings and the light brown wood piles adjacent to them. The landscape softens as it furthers from the mill, and the scene is devoid of people; the ground appears as clinical as the Towers’ office: smoke billows from the stacks without any trace of the dirt, grit, or sweat of the laborers within. Drawing on Burke’s notion of sublime and the awe associated with the all-encompassing gaze, the mill was rendered appealing due to the complexity of the totalizing system it represented, its massive scale, and its promise of capital.

Glossing Over

The coating of the paper, for which the Rumford mill became known within the industry, is also connected to the historiography of the sublime, since it is based on visuality and seeing. Unlike views of the mill, however, the paper’s glossy coating addresses capitalist consumption and commodification: surface effects, fetishistic adherence, glamor and spectacle, as well as durability. By the 1930s, the prints or papers most likely to be preserved were regarded as luxury products, including glossy illustrated magazines, or “slicks.”24See, among others, David Reed, “’Rise and Shine: The Birth of the Glossy Magazine,” The British Library Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Fall 1998), 256-268; and Kevin J.H. Dettmar and Stephen Watt, eds., Marketing Modernisms: Self-Promotion, Canonization, Rereading (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997). In the 1960s, a Chicago newspaper referred to the Rumford Mill and similar mills in New England as the Tiffany of the industry due to the coated finishes they produced and the “high-quality” label that came with paper that could be sold at higher prices.25Francis, “Pulp and Paper Mills,” B14.

In his description of the American technological sublime, Nye notes that the concept of the sublime applied more to onlookers of the mill than to the workers on the mill floor. Drawing on studies of a paper mill in Lowell, Massachusetts, he argued that many workers had varicose veins from standing for 13 hours per day; others suffered from respiratory problems due to poor ventilation; some went deaf due to the rumbling and clanking. As one physician who studied Lowell’s Merrimack Company in 1849 found, factories were unhealthy and “less cared for than our prisons.”26Nye, American Technological Sublime,117.

Yet as Edmund Burke wrote during the eighteenth century, the experience of the sublime was predicated on a feeling of relative safety. The terror-inducing and overwhelming threats of the sublime stem from a position of conscious physical security; otherwise, the sublime would be horrifying and undermined. “Having considered terror as producing an unnatural tension and certain violent emotions of the nerves,” Burke writes, “it easily follows, from what we have just said, that whatever is fitted to produce such a tension must be productive of a passion similar to terror, and consequently must be a source of the sublime, though it should have no idea of danger connected with it.”27Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry, 193, (emphasis added).

Chlorine gas processing for bleaching paper, Oxford Paper Company. n.d. Credit: Rumford Historical Society. Image courtesy of Aaron Cayer

In the River Valley, the smoke from the mill stacks and the stench from the clarifier pools of the mill festered in the valley, while the fumes, heat, and steam emitted from the pulping, treating, coating, and drying process stung the eyes of millworkers, dehydrated and exhausted them, and toxified their bodies. Stories of cancer, death, and illness colonized family gatherings and shaped the town’s public identity. In 1991, an article published in the Los Angeles Times featured four people diagnosed with rare non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, all who lived in “Cancer Valley,” though not all medical experts were convinced that the mill was to blame.

The report led to a seven-year, 8.8-million-dollar study of paper workers’ health at 52 pulp and paper mills, led by Johns Hopkins University epidemiologist Genevieve Matanoski and funded by the American Paper Institute. The study proved inclusive. “The project has examined the mortality of workers in the pulp and paper industry and found that their overall mortality and their mortality for most specific diseases are low compared with the US population as well as state and county standards. However, examination of subgroups of workers suggests that their mortality may differ depending on different pulping processes and work areas in the industry … Therefore, these findings raise questions that must be answered with more in-depth studies of processes, work histories, and exposures in the industry.”28Genevieve M. Matanoski, et al. “Industry-Wide Study of Mortality of Pulp and Paper Mill Workers,” American Journal of Industrial Medicine 33 (April 1998), 364.

This lack of clarity built on a long history of dismissal, denial, and inconclusion. One local doctor, Dr. Edward Martin, attempted to publicize what he thought was happening to workers and their families. “One day in 1981, a small package landed on Doc Martin’s desk,” Kerri Arsenault writes in Mill Town. She continues:

The package contained a four-year study conducted by the American College of Surgeons using data from over 700 hospitals in the US representing over 1.5 million cancer cases from 1972 to 1986 on cancer rates in the United States. Prostate and colon cancer were almost double the national per capita average. Cancers of the uterus, cervix, pancreas, and rectum were also significantly higher than the rest of the nation. Doc Martin brought the report to the board of directors at Rumford’s hospital. “They said the report was bullshit,” Terry [Dr. Martin’s widow] says. “After they saw it, the report disappeared.” Subsequently, the Maine Department of Health conducted a Chronic and Sentinel Disease Surveillance from 1984 to 1986, which showed a high incidence of lung disease, aplastic anemia, and cancer in our community. The state epidemiologist said those findings were just preliminary and inconclusive.29Arsenault, Mill Town: A Reckoning with What Remains, 34.

Even further, in the mid 1980s, the EPA found high levels of dioxin—a known and harmful by-product of the bleaching and waste incineration processes at paper mills—in fish from Maine’s rivers. Those from the local Androscoggin River were ranked among the highest. But the Maine Department of Environmental Protection argued that the levels were “not very severe at all,”30Arsenault, Mill Town: A Reckoning with What Remains, 34. Arsenault writes in her book, even though dioxin was known to be toxic. Dr. Martin wrote letters to the then-Governor Angus King, and his claims were dismissed. He was reported to the IRS, the State Board of Medicine, the State Medicaid program, the Medicare program, and he was even denied access to the hospital. “My husband, he tried to speak up about what was happening,” Dr. Martin’s widow explained to Arsenault. “When he stumbled on what he thought was causing all the cancer in town, they did everything to destroy us.”31Arsenault, Mill Town: A Reckoning with What Remains, 30.

While the mill’s owners have made changes to processes and waste protocols, limits on the consumption of Androscoggin fish remain in place, as Maine toxicology studies continue to reveal that fish dioxin levels are still higher in Rumford sampling points than elsewhere in the state—still at cancerous levels32Andrew Smith and Eric Frohmberg, “Evaluation of the Health”, iii.—while local officials continue to downplay the need for attention.33For example, in 2020, the Director of Economic Development for Rumford, George O’Keefe, who began his new position in 2018, argued that the “Cancer Valley era of the 1980s” did not represent Rumford’s “present or future.” See: Routhier, “Going home to a papermaking past.” As of 2018, lung cancers in the county were still “significantly higher” than elsewhere in the state, and cancer rates in Maine, as a whole, were markedly higher than US rates for nearly the fiftieth year in a row.34Maine Annual Cancer Report, 54.

Conclusion: Re-humanizing

When the mill formed during the Gilded Age, the rise of industries was linked to growth, expansion, and rebirth in the US, while individual aspirations, such as those by Hugh Chisholm, were defined as power. Workers were told that they could achieve anything if only they put their minds to it, and in places like the Rumford paper mill, inspirational quotes that flattened perceived hierarchies between workers and managers peppered company newsletters. Media scholar Janice Peck has argued that this conception of the empowered individual has again come to typify the neoliberal present, characterized by the commodification of doctrines based on personal responsibility and the belief in the power of individual will to overcome material obstacle and social injustice.35Peck, The Age of Oprah: Cultural Icon for the Neoliberal Era, 62.

It is not surprising, then, that the books and films about the River Valley sprang to best-selling success, including Monica Wood’s engaging book about the mill town that was spotlighted by Oprah Winfrey as part of her summer reading list. The narratives upheld by Winfrey are appealing, Nicole Aschoff argues, “because they hide the role of political, economic and social structures. Instead of examining the interplay of biography and history, they eliminate it, making structure and agency indistinguishable. In doing so, they make the American Dream seem attainable. If we just fix ourselves, we can achieve our goals.”36Aschoff, The New Prophets of Capital.

In these narratives, the paper mill maintains a central role as a modern structuring and disciplining institution for everyday life, and the experiences of workers submitting to and attempting to cope with the mill’s established parameters are now printed and sold on the very paper it produces. Without the modern master narrative, what else might structure everyday life in the town? Mill work is required by individuals, these texts explain, in order to produce themselves and to produce their families.

Wood writes: “Mum wondered later whether those heedless men hastened his end; heedless men, and long hours, and poisons that found a way into his big pumping heart. Sulphur dioxide. Calcium bisulphate. Hydrogen sulphide. Methyl mericaptan. Dimethyl sulphide. ‘The man lived in that place,’ she often said, which meant that he’d also died in that place, bit by bit, no matter how much joy he took from the work…37Wood, When We Were the Kennedys, 107. You proved yourself not by losing your temper, not losing your focus, not losing your life. Dad proved himself quick. Your father wasn’t afraid of work, Mum always said … Don’t go in there, Dad, I shout at his straight, long-gone back, that work will kill you, but of course he goes in there. He has to. He wants to. And if he doesn’t, there’s no work at all, no settling here, no Mum, no us. So he goes in. Before Local 900. Before “air-quality index.”38Wood, When We Were the Kennedys, 104.

Yet as the mill continues to provide a modern structuring narrative for so many, might it be possible to push against the forces of the technological sublime? How might the community reshape and redefine itself after the mill is no longer? How might the written text function as a way to challenge the reproduction of the mill worker?

Kerri Arsenault’s text brings us closer, since it begins to dig into the politics of the town, the history of loss and corruption, and the damaging environmental and health consequences brought on by the mill. She concludes by suggesting that the various data that reveal material, social, and environmental truths produce ambiguous lives: “And it is the overall ambiguity—when the arbitrary overshadows the reasonable—that leaves people helpless, paranoid, confused, angry, incredulous, psychologically adrift, as I was starting to feel myself.”39Arsenault, Mill Town: A Reckoning with What Remains, 57.

In other words, Arsenault argues that ambiguity follows when the structuring narrative—the omnipresent mill, its sublime lure, and the gloss necessary to maintain it—is stripped away or gone. However, this loss of a totalizing narrative is one of the fundamental challenges presented by postmodernity, and it is one the community has yet to confront, since the community members and workers produce themselves as “whole” through the mill—“our” mill. Feelings of deprivation, disappointment, and confusion naturally follow, geographer Frederic Jameson argues, when the pieces of our individual experience do not fully fit together as part of a whole.40Jameson, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act.

Without the mill, the ambiguity of self without the mill-as-structuring agent and the seemingly vulnerable status of the individual may, however, encourage a shift away from a focus on individuality and instead toward new collectives; individuals may seek to identify with new communities beyond the River Valley, or perhaps the River Valley could devise a new structuring narrative altogether.

Biographies

PhD, is an architectural historian and assistant professor of architecture history at the University of New Mexico. He was raised and educated in the town of Rumford, Maine—the largest of those within the River Valley. He left Rumford for college after graduating from Mountain Valley High School. Cayer studied architecture at Norwich University in Vermont, where he earned undergraduate and graduate degrees, as well as at UCLA, where he received his PhD in architecture history.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.

Bibliography

Arsenault, Kerri. Mill Town: A Reckoning with What Remains. New York: St. Martin’s, 2020.

Aschoff, Nicole. The New Prophets of Capital. London: Verso, 2015.

Bennett, Randall H. The Mount Zircon Moon Tide Spring: An Illustrated History. Bethel: R.H. Bennett, 1997.

Bolton-Fasman, Judy. “7 Tales That Will Transport You to Another Time and Place.” Oprah. Last modified 06/25/2012. https://www.oprah.com/book/when-we-were-the-kennedys?editors_pick_id=38221.

Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful [1757]. London: Thomas M’lean, Haymarket, 1823.

Burns, Elliott E. “Bud”, David Gawtry, and Nghia Ha. “For the Love of Paper.” Maine Memory Network: Western Maine Foothills Region. Accessed July 2, 2020. http://foothills.mainememory.net/page/3838/print.html.

Dettmar, Kevin J.H. and Stephen Watt, eds. Marketing Modernisms: Self-Promotion, Canonization, Rereading. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997.

Fallon, Tom. “Holding.” In Salt and Pines: Tales from Bygone Maine, edited by Jeanne Mason and D. L. Soucy, 160-173. Charleston: The History Press, 2011.

Francis, David R. “Pulp and Paper Mills: Industry ‘Tiffany’.” The Christian Science Monitor, (January 1961): B14.

Jameson, Fredric. The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1981.

Leane, John J. The Oxford Story: A History of the Oxford Paper Company 1847- 1958. Rumford: Oxford Paper Company, 1958.

Maine Department of Health and Human Services. “The Maine 2018 Annual Report of Cancer.” Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/public-health-systems/data-research/vital-records/mcr/reports/documents/ACR-Maine-2018-Annual-Report-of-Cancer-081219.pdf

Matanoski, Genevieve M. et al. “Industry-Wide Study of Mortality of Pulp and Paper Mill Workers,” American Journal of Industrial Medicine 33, no.4 (April 1998): 354-365.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964.

Nine Dragons Paper (Holdings) Limited. “Annual Report 2019/2020.” Accessed January 27, 2021. https://doc.irasia.com/listco/hk/ndpaper/annual/2020/ar2020.pdf.

Nye, David E. American Technological Sublime. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994.

Reed, David. “’Rise and Shine: The Birth of the Glossy Magazine.” The British Library Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Fall 1998).

Smith, Andrew and Eric Frohmberg. “Evaluation of the Health Implications of Levels of Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-Dioxins (dioxins) and Polychlorinated Dibenzofurans (furans) in Fish from Maine Rivers.” Maine Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/environmental-health/eohp/fish/documents/finaldraft-eval-of-pcdd.pdf

The Rumford Comprehensive Plan Committee and Androscoggin Valley Council of Governments. “Rumford Comprehensive Plan: Section I Inventory & Analysis.” Accessed January 27, 2021. https://rumfordme.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/rumford-comp-plan-ia-sm.pdf.

Toomey, Daniel P. Thomas Charles Quinn, and Massachusetts Board of Managers, World’s Fair, 1893. Massachusetts of Today: A Memorial of the State, Historical and Biographical, Issued for the World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago. Boston: Columbia Publishing Company, 1892.

Tower, A.B. Machine for Grinding Pulp from Wood. US Patent 311,212, issued January 27, 1885. Wolfinger, Kirk, dir. The Rivals. Aired September 11, 2010, on Smithsonian Channel. https://www.smithsonianchannel.com/shows/the-rivals/0/135757

Varney, George J. A Gazetteer of the State of Maine (Boston: B. B. Russell, 1881), p. 483

Wood, Monica. When We Were the Kennedys: A Memoir from Mexico, Maine. New York: Mariner Books, 2012.