Rethinking public space

Design consultancy PORT helps cities across the United States create innovative community spaces.

March 2, 2020

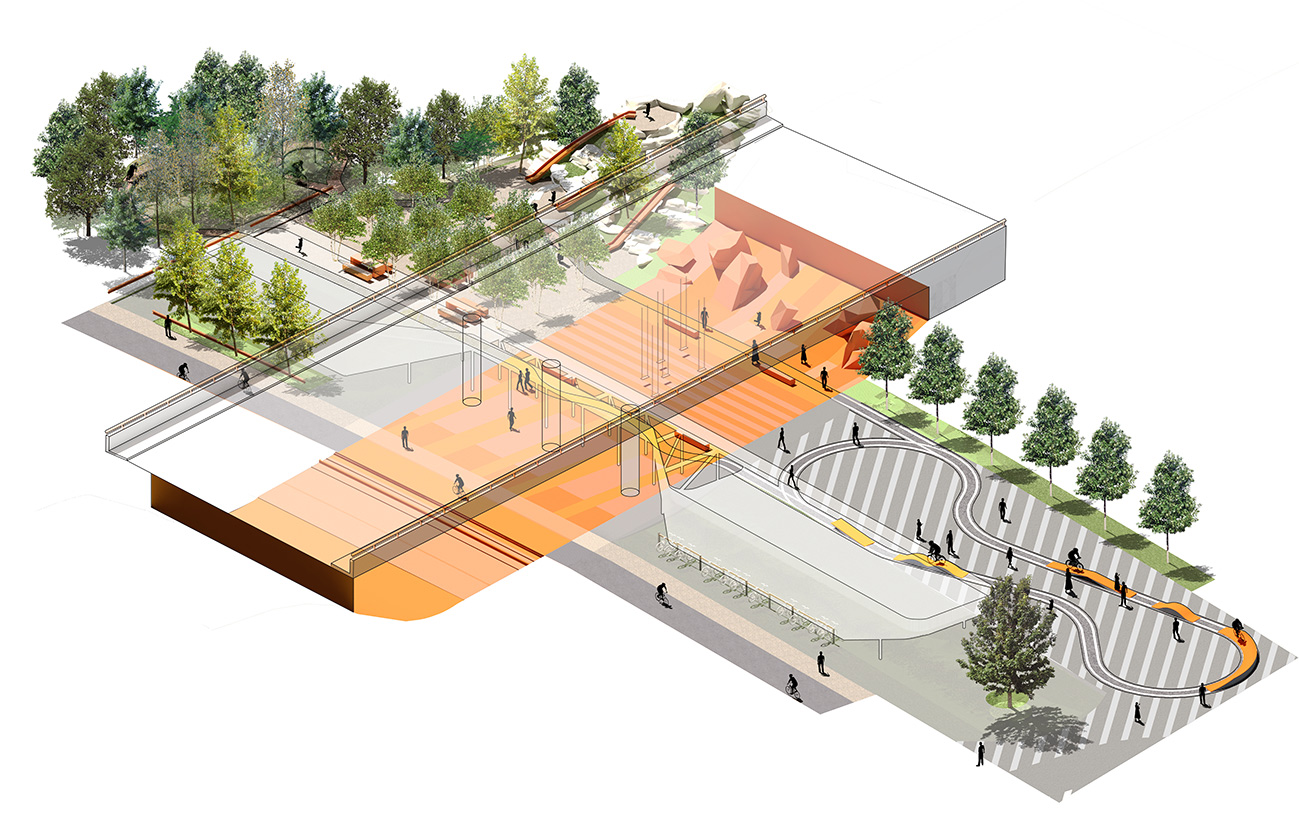

PORT's design for the Urban Wilderness Gateway in Knoxville, Tennessee, is transforming a highway underpass into a formal entry to a park. Credit: PORT

PORT is a 2020 Emerging Voice.

By Sarah Wesseler

In the early 1980s, the Tennessee Department of Transportation began construction on a four-lane highway designed to link downtown Knoxville to a larger freeway network. But the project stalled before the first two miles were built, and for decades the James White Parkway languished as a rarely used stump dead-ending in the heart of South Knoxville.

Over the years, some of the land set aside for the unfinished portion became popular with outdoors enthusiasts. These and adjacent properties gradually coalesced into a 1,000-acre recreation area known as Knoxville’s Urban Wilderness. When plans to finish the parkway were announced in 2013, then-mayor Madeline Rogero helped defeat them, largely in order to preserve this unique public space.

But while the Urban Wilderness had become an important amenity for Knoxville, the municipality recognized that it lacked a coherent structure because of its history of ad hoc development. To address this concern, it commissioned design firm PORT to turn the underpass where the James White Parkway dead-ended into a formal gateway to the park.

PORT’s design, now in construction, transforms the underpass into a multigenerational play space featuring an event plaza, children’s bike circuit, swings, and a climbing wall, all tied together with playful surface treatments inspired by transportation infrastructure. On the other side of the highway, the design eases visitors into the “wild” setting with leafy picnic grounds and play features that emerge from an existing embankment.

PORT co-founders Christopher Marcinkoski and Andrew Moddrell were trained as architects, but gravitated over time toward the design of collective and public spaces. “As we got deeper into our careers, we discovered that the public realm of the city is one of those places where you can have enormous impact and touch a very broad audience in a variety of different ways,” said Marcinkoski.

Today, their firm works across the US, helping rethink everything from exurban regions in the New York metropolitan area to the forlorn underside of a Chicago transit corridor.

There’s a growing need for this type of expertise, they say, as more people begin to understand the importance of accessible places where communities of all kinds can gather. “I think the fact that we’re building a 400-acre, highly innovative urban park in a town of 15,000 people in the Smoky Mountains suggests that we’re in a pretty amazing moment in time,” Marcinkoski said. “Cities large and small are recognizing the enormous value of meaningful investment in these kinds of public spaces and amenities.”

But although the will to create public space has increased, many of the municipal agencies and other organizations that initiate such projects (nonprofits and community groups, for instance) have little experience in this realm, and aren’t always sure what steps to take.

“I don’t think we’ve ever gotten a program for any project that we’ve started,” said Marcinkoski. For example, “it might be a project that’s about trying to navigate the underside of a piece of transportation infrastructure, and it’s a place that has fallen into disrepair and is full of garbage and ignored. The question is, what to do with it? How do you start to invite people to feel comfortable occupying it, or at the very least passing through? What is possible there?”

To flesh out a project’s vision, PORT spends the early phases examining the site and its context, searching for opportunities that may have been overlooked in the past. The designs that emerge from this stage often draw out particular aspects of the physical environment, aiming to help visitors see them in new ways.

For a series of summer installations in Philadelphia’s Eakins Oval, for example, the firm emphasized the scale of a football field-sized stretch of pavement that’s typically used as a parking lot.

Brightly colored graphics demarcated distinct zones where visitors could visit a Ribbon Room, cool off in a misting pavilion, or (the most popular option) hang out on a multi-tiered Big Seat, among other activities—encouraging thoughts about the site’s potential to host different uses on a more permanent basis.

PORT also frequently plays up historical or cultural references that may not typically be viewed as worthy of celebration. For the Urban Wilderness Gateway entrance, for example, “rather than trying to change that overpass into something that it’s not, we’re painting many things bright orange and calling up the legacy of the Tennessee Department of Transportation and this abandoned roadway from 40 years ago,” said Moddrell. “Our projects are not just about beautification, but inviting people to reflect on what is there.”

The Knoxville project encompasses two challenges that PORT frequently addresses: underutilized urban sites and large, complex territories with uncertain futures. The practice was originally engaged to work only on the underpass site, but soon realized that the strip of land once intended to host the parkway could be used to improve connections between the city center and the outdoor recreation zone, as well as between different sections of the sprawling Wilderness.

The city government responded enthusiastically to this vision, and PORT helped it work through the practical steps required to make it a reality. “The funding and Tennessee Department of Transportation approval process is pretty cumbersome to unpack, but we’ve managed, and the project is well on its way,” said Moddrell. The project’s first phase, which includes areas near the overpass that were originally intended to host the unbuilt highway, is now in construction. A second phase would build a greenway linking the Urban Wilderness Gateway to downtown Knoxville.

The need to help clients find political and financial backing for projects is a common theme in PORT’s work. “In a lot of cases, it’s about momentum-building,” said Marcinkoski. “It’s about trying to build a larger constituency of institutions, agencies, and the public that can begin to support and pull the resources together for the project as it develops.”

This process can be complicated by the fact that public space initiatives don’t always have a natural home within municipal departments or nonprofit budgets. For another project in Philadelphia, questions arose about who should fund a series of interventions linking the Fishtown neighborhood to the Delaware River waterfront, since the work didn’t fit neatly within recognized categories like wayfinding, public art, or streetscape improvement.

“That creation of an alternative typology can be more challenging from an implementation point of view. But rather than falling into the bucket of the familiar, we like to let things emerge,” Marcinkoski said. “And if they happen to emerge as something that is difficult to categorize, that’s on us as designers and consultants to help our clients navigate how to support it.”

Another issue that complicates efforts to build support for public space is the growing popularity of pop-up installations and events, which many cities now view as a relatively low-cost, high-impact way to bring communities together. For PORT, this trend is worrisome. Marcinkoski and Moddrell believe that temporary projects can be an effective way to test ideas and build momentum for longer-term initiatives, but that public space ultimately requires capital investment.

“We are adamant believers in the value of physical design,” Marcinkoski said.

Explore

Connective spaces and social capital in Medellín

Jeff Geisinger investigates the built environment's impact on social capital in Colombia's second-largest city.

Material flows, ecosystem growth, and urban landscape renewal

Paul Mankiewicz explores ways to improve the environmental, infrastructural, and economic health of cities.

Re-envisioning New York’s branch libraries

The Center for an Urban Future's latest policy report provides a comprehensive blueprint for bringing these vital community institutions into the 21st century.