Rekindling a Southern discourse

Architect Jennifer Bonner’s critical and conceptual practice attempts to redirect attention to the American South.

Jennifer Bonner of MALL is a 2019 League Prize winner.

Bonner spoke to the Architectural League’s Katie Rotman and Sarah Wesseler about her work.

*

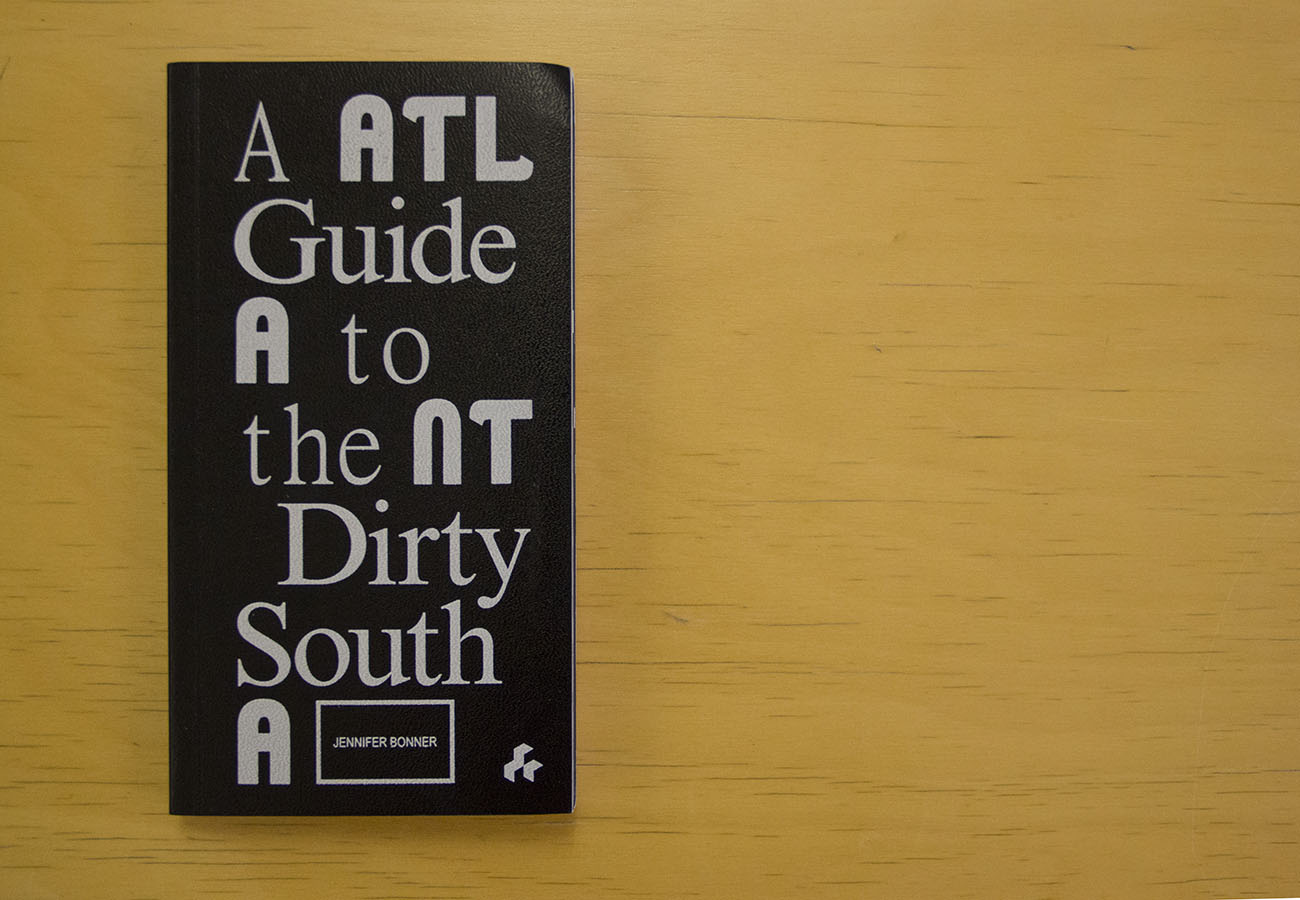

Katie Rotman: Could you talk about A Guide to the Dirty South—Atlanta?

Jennifer Bonner: It’s part guidebook, part architectural manual, part oral history.

A guidebook normally consists of tours that direct tourists to places or things like urban life, art, parks, shopping, or landmarks. We decided not to use those traditional categories, but instead to be much more intentional about how we titled each chapter. We’re cataloging moments in the city, but under provocative positions. So—one chapter is called the Average House; other examples are Rap City and Façade Trafficking. Each chapter of the book argues for a big conceptual project that might happen in Atlanta’s near future.

It’s similar, in a way, to the BeltLine, which is a pedestrian ring that’s getting slowly built out around the city—Atlanta’s version of the High Line. That was originally a conceptual idea about how development might happen in the city. It grew out of a thesis project at Georgia Tech by a student who later started working for Perkins+Will, and it’s getting built and changing the city in a very big way.

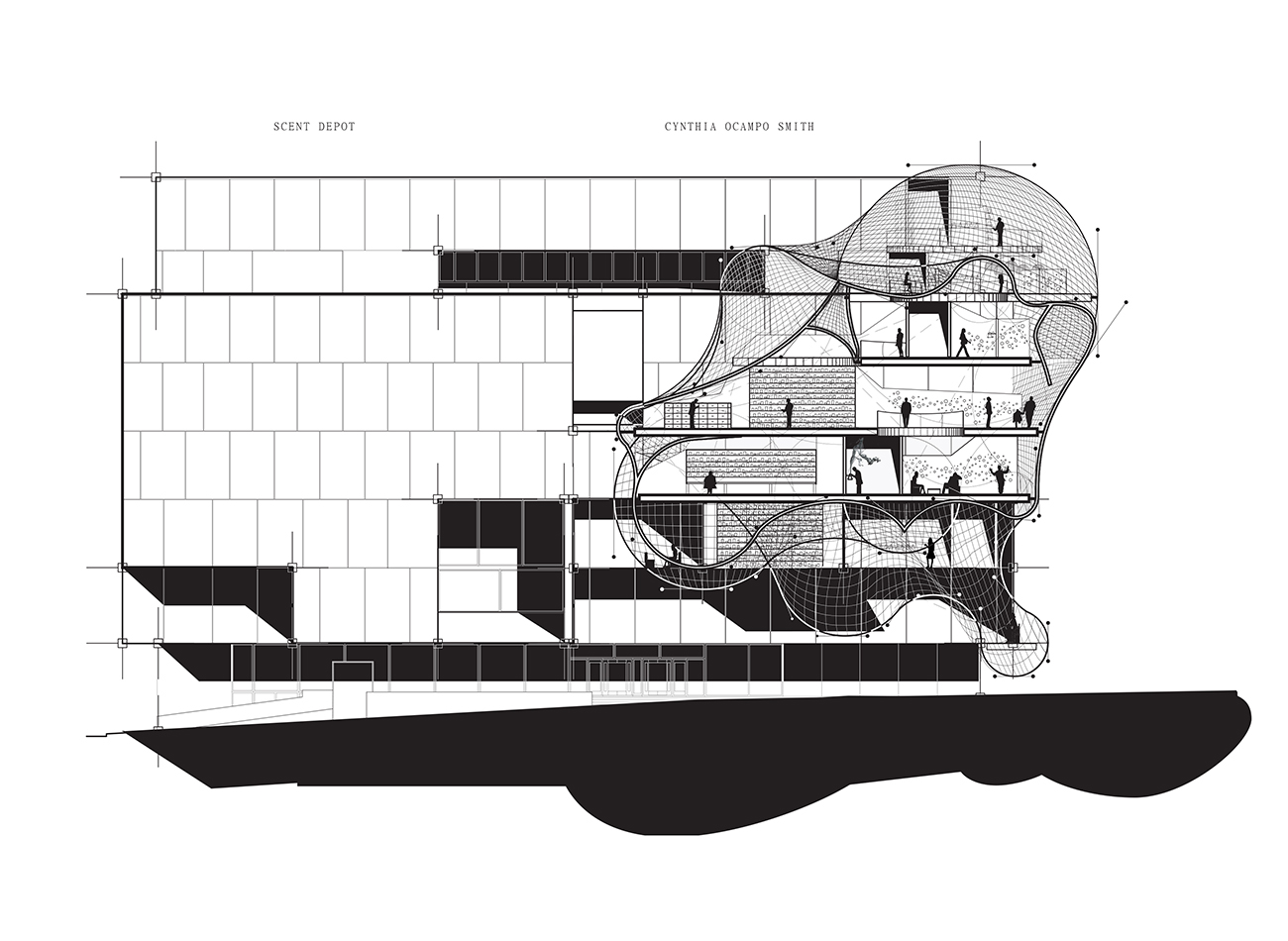

As another example of what might initially seem like a far-fetched idea but could also be considered a real proposal for future development, one chapter in our book is called Geography of Smells. It talks about preserving Atlanta’s historical scents by proposing a large-scale renovation of Marcel Breuer’s Central Library—an architectural icon in downtown Atlanta—to allow for scent storage and public accessibility.

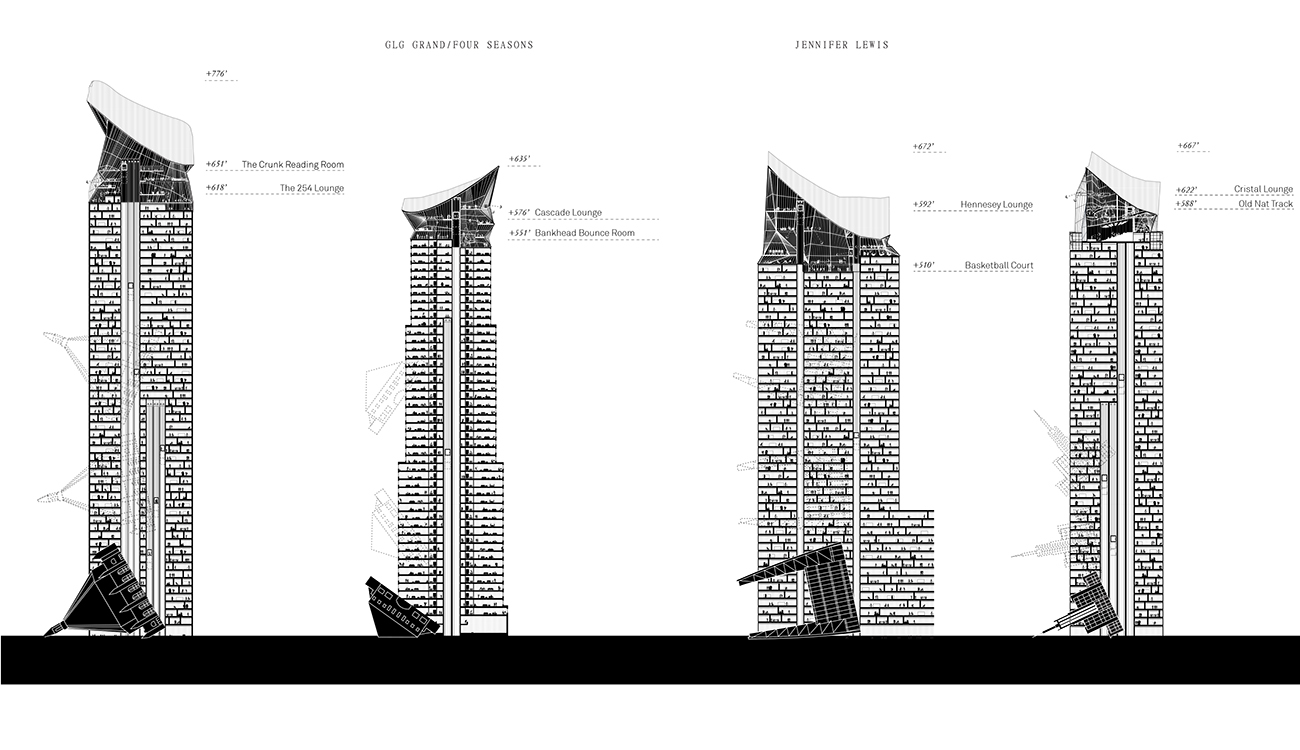

Another chapter, Top Floors, proposed cutting off the top fifty feet of several mid-rise office towers to offer public amenities—ultimately producing a top-floor urbanism in midtown Atlanta. Our idea was that the original tops of buildings would sit at the tower’s base, posing as public art.

A Guide to the Dirty South was produced with graduate students at Georgia Tech, 12 women and 2 men. The last building in each chapter is imagined, not real. We gave each one an address, pointing tourists to proposals for what could be in the city, presented as an architectural drawing. We worked with a graphic designer, Neil Donnelly, to create a series of gatefolds to exhibit them.

In addition to these conceptual proposals, half of the book is filled with interviews with folks in Atlanta, and also with architects who have looked at cities like this in the past. We interviewed Denise Scott Brown; we talked to a local chef, an urban farmer, and a preservationist. We interviewed the founders of Goodie Mob—Big Gipp, Khujo, and T-Mo—who coined the term the Dirty South.

Goodie Mob spoke to us about the very real issues stemming from race-based oppression impacting the city of Atlanta. Before replacing Civil War monuments became a national news story, they were talking about this issue in the book. Atlanta is the birthplace of Dirty South rap. One of the things we asked them is, why aren’t there markers or venues in the city celebrating this explosion of music?

Sarah Wesseler: What’s the relationship between this book and the architectural projects you’ve done since? It seems like the idea of researching vernacular design and culture in particular places runs through a lot of your work.

Bonner: I haven’t thought about it like that, but I like that reading. All 14 chapters in the guide are basically examples of how to read a phenomenon, a pattern, or an oddity within a city, culminating in a projective idea for its future. And that is essentially what I’m doing in Domestic Hats, too. I’m making a connection between socioeconomic differences, neighborhoods, and the formal oddities you see in rooflines, and I’m suggesting the “roof plan” as a way of organizing and spatializing domestic interiors.

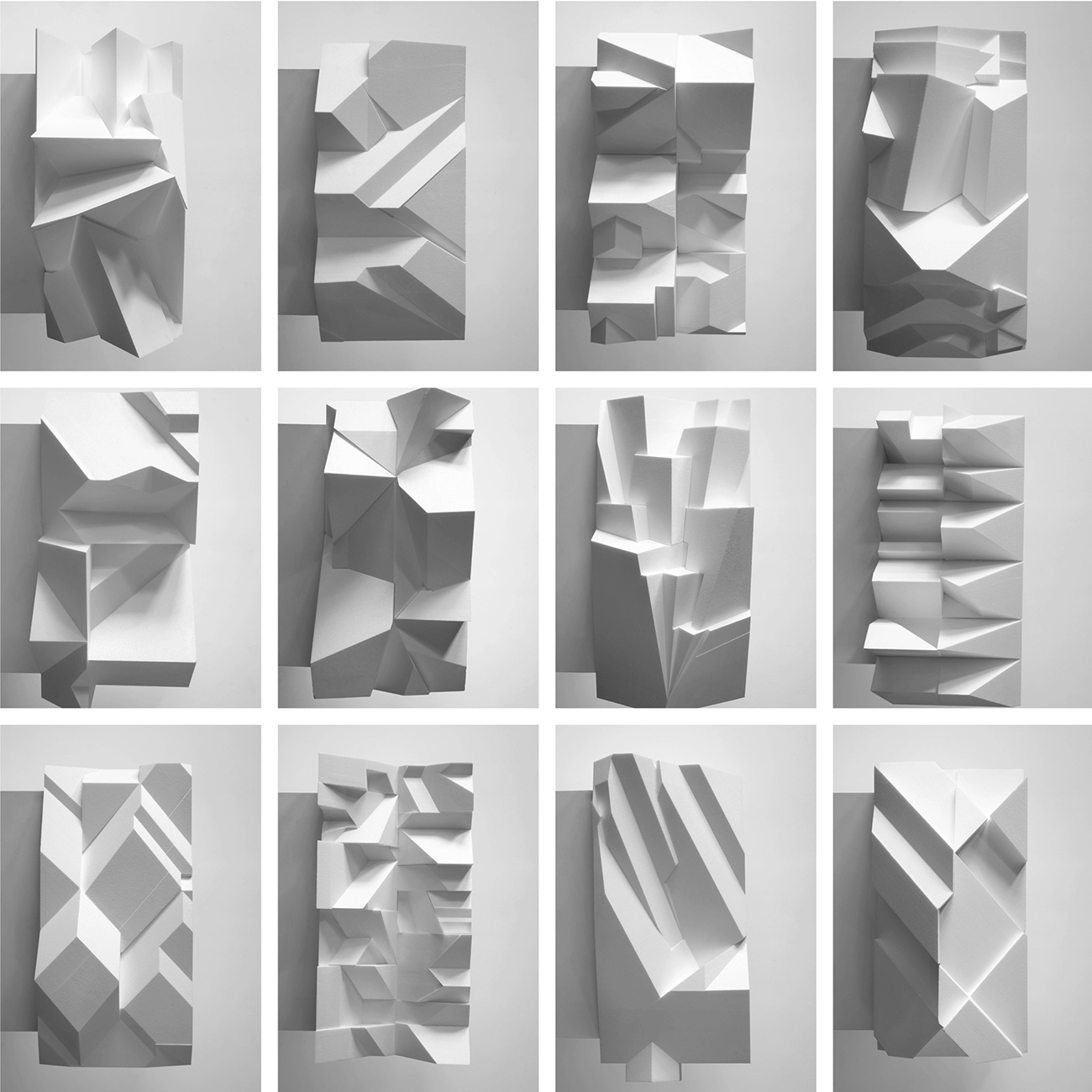

And then in Best Sandwiches, I’m exhaustively looking at how things stack and imagining how facades might differ depending on what level you’re inhabiting within what I refer to as a “BLT” mid-rise office tower.

Architectural questions are the very center of my projects, and that’s also how the guidebook is framed, in a way. So, yes, I could see how it’s influenced a methodology for my work.

Rotman: What are you working on now? What are your plans looking ahead?

Bonner: My first move outside of a gallery—not as a temporary installation, but as capital A-architecture—is my project Haus Gables. It was a very liberating experience to build while at the same time pushing an innovative wood product like cross laminated timber, and it became really interesting to me as a mode of practice. I self-developed and self-funded the project, which allowed me to experiment with faux finishes and materiality without the major pushback I would have likely had from a traditional client.

I’m certainly not the first architect to act as a developer, of course. The immediate example in Atlanta that I always reference is John Portman. And it fairly common for architects in the generation before me to have family members commission their first work. But that’s not typically the case anymore, so we have to invent new ways of getting things done.

I have two projects on the very near horizon. The first explores building not just one, but several single-family houses with cross laminated timber on a small plot of land in Atlanta. I want to focus on the idea of collectivity in a tight urban site. It also becomes a more interesting model in terms of affordability.

I’ve always had one foot in academia, one foot in practice; I’m constantly conceptualizing, exhibiting, lecturing, writing about my projects. They stay conceptual for a lengthy amount of time, and there’s a strategy to build at least one of each as proof of concept.

So the second project on the horizon is Best Sandwiches, where, as I’ve done before, I start high-concept and work with a gallery, and write and lecture—in this case, about how architecture might stack. I’ve turned that series of nine conceptual models into a real building called Office Stack. It’s a mid-rise tower currently on the boards, located in Huntsville, Alabama.

Rotman: You recently returned to Harvard to teach. Has being back in the northeast had an effect on your practice?

Bonner: When I started teaching at Georgia Tech in Atlanta, it was kind of a homecoming to the South for me, being from Alabama. It was very exciting. I was trained on the East Coast, I had been teaching on the West Coast, and had lived in London and Istanbul in practice.

When I was hired to teach at the GSD, I wanted to find a way to stay invested in Atlanta. I wanted to figure out how to not totally be an East Coast academic, but somehow continue to push a Southern discourse.

There really is a lack of attention on the South within the discipline of architecture. I believe there’s opportunity to redirect people’s attention, to show them that there has been a radicality in Atlanta. The guidebook was a way of doing that.

It’s definitely something I think about in my practice, too. Haus Gables is located in Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward neighborhood, near a lot of the places the guide talks about.

Wesseler: Why do you think the South gets overlooked within the design field?

Bonner: In the late ’80s, there was a very strong conversation amongst architects in Atlanta. The members of Architecture Society of Atlanta were really trying to center a discussion. Merrill Elam of Mack Scogin Merrill Elam was a guest editor of Art Papers, and she and this society turned the magazine into a grab bag of sorts rather than a traditional contemporary arts magazine, and stuffed all these contributions from architects into it. At the same time, the members of the society were building their first buildings—they were going for it, there was momentum behind it. And then there was the conversation around Critical Regionalism also happening in the ’80s.

But there was a lull after that. It was almost like people pushed back against the awful label of being a “Southern architect”. They were also trying to be global architects.

Besides editing the guidebook, I don’t have any interest in creating a band or a society around contemporary architects in the South. It’s really just about, how can my work be situated there, while also pointing the field to other unnoticed experiments from the recent past?

Although, having said that, I am interested in starting a new school of architecture in Atlanta. It seems like the right time for a new model to emerge.

Rotman: How did you first develop this idea of creating a new institution?

Bonner: It’s something I’ve been thinking about since I began teaching. I kept feeling bogged down in the political machine of state and Ivy League institutions. For example, when I was teaching at Georgia Tech, there were 33 faculty, three of whom were women.

Instead of trying to change a backward system that probably can’t be fixed, why not just reinvent it, then show everyone how to do it? I think students would be more interested in that model. Nobody wants to go to the white guy school anymore.

Interview condensed and edited.

Explore

BLDGS lecture

The founders of Atlanta firm BLDGS present their work.

In conversation: Marlon Blackwell and Rick Joy

Blackwell and Joy reflect on first meeting 15 years ago, approaches to teaching, and a shared sensitivity to place while "transgressing the vernacular" in their work.

Flipping things upside down

In her Not White Walls project, Mira Hasson Henry explores issues of personal expression, cultural identity, and architectural value systems.