Re-Envisioning New York’s Branch Libraries, released by the Center for an Urban Future on September 15, 2014, provides a comprehensive blueprint for bringing these vital community institutions into the 21st century. Written by David Giles, Jeanette Estima, and Noelle Francois, the report is the latest in CUF’s ongoing research on branch libraries in New York City. In conjunction with and as a complement to this research, The Architectural League is collaborating with CUF on a design study that will articulate new architectural, financial, and programmatic possibilities for branch libraries, to be presented later this fall.

The report’s introduction is reprinted below. Read the full publication on CUF’s website.

At a time when far too many New Yorkers lack the basic language and technological skills needed to access decent-paying jobs, branch libraries have become a critical part of New York City’s human capital system, the go-to place for upgrading one’s skills and a key platform for economic empowerment. Libraries also have stepped in as critical resources as record numbers of freelancers are looking for a place to do their work, students from pre-k through 12th grade need to supplement their studies with enrichment programs, and neighborhood residents want a “third place” to meet with neighbors and keep up with events. As Superstorm Sandy revealed in 2012, libraries are even an important part of building and maintaining strong social networks necessary for community recovery efforts.

At a time when far too many New Yorkers lack the basic language and technological skills needed to access decent-paying jobs, branch libraries have become a critical part of New York City’s human capital system, the go-to place for upgrading one’s skills and a key platform for economic empowerment. Libraries also have stepped in as critical resources as record numbers of freelancers are looking for a place to do their work, students from pre-k through 12th grade need to supplement their studies with enrichment programs, and neighborhood residents want a “third place” to meet with neighbors and keep up with events. As Superstorm Sandy revealed in 2012, libraries are even an important part of building and maintaining strong social networks necessary for community recovery efforts.

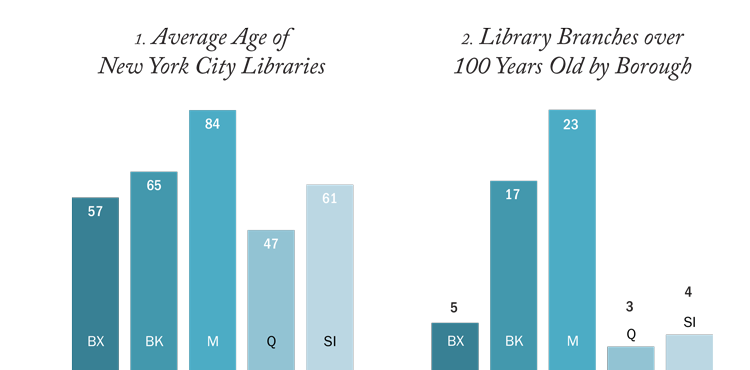

Yet, despite expanding needs and growing circulation and program attendance numbers, New York isn’t coming close to fulfilling the promise of its community libraries. The average branch library in New York City is 61 years old, and a significant share of the branches suffer from major physical defects such as a lack of light and ventilation, water leaks and over-heating due to malfunctioning cooling systems. In addition, the vast majority of branches — including “newer” ones built in the past 40 years — are poorly configured for how New Yorkers are using libraries today, with little space for classes, group work and individuals working on laptop computers. Meanwhile, the libraries have just started to scratch the surface when it comes to taking advantage of new technologies, and they have only begun to design branches in ways that improve how they serve specific populations, such as seniors and teens.

More than half of the city’s 207 library buildings are over 50 years old and a quarter were built at least a century ago. With such an aging building stock, it’s not surprising that the city’s libraries are on the verge of a maintenance crisis. The city’s three library systems have at least $1.1 billion in capital needs, and that’s mainly just to bring the branches into a state of good repair. Bringing them into the 21st century would require an even greater investment.

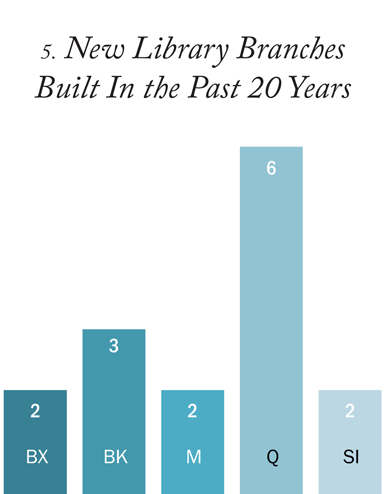

Cities from Seattle and San Francisco to Chicago and Columbus have recently undertaken multi-year campaigns to rebuild or renovate a significant share of their libraries. But New York City has made barely any headway in addressing its libraries’ infrastructure needs. Each year only a tiny fraction of the branches that need to be renovated — much less replaced — receive any funding to do so, and the few that do receive support can take years to be repaired because of the city’s time-consuming approvals and contracting process. Only 15 new libraries have been built in the past 20 years.

Over the past decade, the Bloomberg administration’s major capital investments in new parks, schools and cultural institutions have had a transformative impact on the city. It’s now time to make a similar game-changing investment to repair, modernize and expand the city’s public libraries. This first-of-its-kind blueprint for re-envisioning New York’s branch libraries provides a number of achievable options and ideas for doing so.

Nearly two years ago, the Center for an Urban Future published Branches of Opportunity, a report documenting that New York City’s public libraries have become more vital than ever, and are serving more New Yorkers in more ways than ever before. In this new report, we provide an exhaustive analysis of the libraries’ capital needs and offer a comprehensive blueprint detailing more than 20 actionable steps that city government and the libraries themselves could take to address these needs.

Among other things, we propose reforms to the capital funding and contracting process and detail specific approaches for realizing efficiencies across the libraries’ physical plants. In addition to outlining strategies for new branch buildings and renovations, we describe how the libraries could better engage communities in the planning of new libraries and how the city could tie library investments to broader community development and affordable housing goals. With these tools, we believe the de Blasio administration has a golden opportunity to not only transform libraries across the five boroughs, but to put them on a more sustainable path for the growing number of residents who depend on them.

In the course of our research, we visited 50 libraries across all five boroughs and surveyed over 300 librarians about the conditions in their branches. We analyzed branch-by-branch performance data as well as key metrics about their size, layouts, amenities and capital needs. We interviewed library administrators and experts in more than 25 cities across the nation and around the world, which helped us understand funding and design strategies that have worked and could serve as models for New York. We also spoke with more than 50 New York-based library staff members and experts in a wide variety of fields, including library science, community development, education and government finance. In partnership with The Architectural League of New York, we also held two focus groups composed of 15 prominent designers and architects.

The set of programmatic demands placed on New York City’s public libraries is immense and growing all the time: In addition to providing books and other learning materials, libraries are called upon to serve as a place where neighbors can gather and talk, hold meetings about community issues and engage in clubs and other group activities. They’re an increasingly important information resource for anyone looking to find out about government services and requirements. And in an era when English and digital literacy are essential for job seekers, and the need to pick up new skills has never been greater, libraries are the city’s only free and open lifelong learning resource. As such they need to provide sufficient space for adult learners and after-school programs.

In fiscal year 2013, the city’s 207 branch buildings greeted nearly 36 million visitors, or approximately 160,000 every day they were open. Libraries circulated 61 million materials citywide and enrolled over 2.4 million people in their public programs, including everything from story time for elementary school kids, to English language classes for immigrants, to film editing workshops for teenagers. And despite dwindling budgets, these performance numbers have been growing rapidly over the last decade. Between fiscal years 2003 and 2013, circulation increased by 46 percent and program attendance by 62 percent.

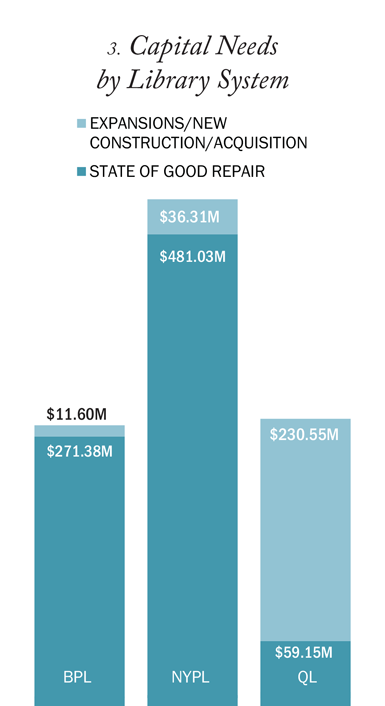

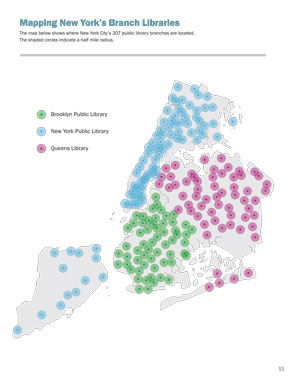

At the same time, however, the city’s three library systems — including the New York Public Library (serving the Bronx, Manhattan, and Staten Island), the Brooklyn Public Library and the Queens Library — have struggled to keep many of their older branches in a state of good repair, much less current in meeting the space and technology needs of today’s users. The three library systems have prioritized nearly $1.1 billion in capital needs, spread across 178 branches, or 86 percent of their buildings. Of that, approximately $812 million is for state of good repair and interior renovation projects, and $278 million is for site acquisition and new construction.

Excluding cost estimates for expansions and replacement buildings, 59 different branches across the city each have $5 million or more in needs, including 18 in Manhattan, 16 in Brooklyn, 16 in the Bronx, five in Staten Island and four in Queens. The average age of these buildings is 81 years old.

According to Roof Top Services, the most common state of good repair problems involve malfunctioning mechanical equipment, leaky roofs, overburdened electrical distribution systems, and a lack of accessibility for the elderly and physically disabled, though many more haven’t been renovated in decades and suffer from missing or deteriorating ceiling panels, old carpeting and a lack of ventilation and light as well. In all, 64 branches across the city need HVAC repairs or replacements, 55 need roof repairs, 55 need to be made ADA compliant, 35 need boiler repairs or replacements, 32 need electrical system upgrades, and 23 need new elevators.

In many cases, these basic infrastructure shortcomings cause serious service disruptions. At the Brighton Beach branch in southern Brooklyn, for example, staff members have to move a bank of computers in the adult collection every time it rains because of a leak in the ceiling. And at Brooklyn Heights, the doors are often closed early because the HVAC system can’t keep the interior temperature at a comfortable level. “Extreme temperature imbalances exist all year long,” says assistant business librarian Paul Otto, “and frequently trigger customer complaints [even when we don’t have to close].”

While service disruptions like these happen in all five boroughs, Brooklyn has undoubtedly lost the most service hours from extreme temperatures and other serious infrastructure emergencies. In 2013, Brooklyn branches experienced 140 unplanned closures, adding up to approximately 540 service hours. Eleven branches were forced to close for two or more days. Most recently, the New Lots branch in East New York lost nearly two weeks in January and February when its 57-year-old boiler finally stopped working.

Meanwhile, over two dozen branch buildings, particularly in Manhattan and the Bronx, are warehousing large rooms — or even entire floors in some cases — that could be used for patron services if they had the funds to modernize the core infrastructure in these spaces. At least 14 branches — 11 in Manhattan alone — have empty custodial apartments averaging 1,000 square feet on their top floors, and over a dozen have empty or underutilized basements or third floors that could be reactivated if they were brought back up to code. “These are ideal spaces for after-school programming,” says George Mihaltses, NYPL’s vice president of community and government affairs, “but unless they have walls replaced and other capital needs addressed we can’t use them.”

Reconfiguring layouts and adding basic service amenities to meet modern usage patterns and needs is another widespread problem. Far too many branches struggle to provide enough space for people to sit down and plug in their laptops and other mobile devices, for example. Out of the 45 branches we visited for our site surveys, 58 percent (or 26 locations) had plugs for ten devices or fewer, and 18 percent (or eight locations) had plugs for just one or none at all. In some cases, even very popular branches had a dearth of electrical outlets for patrons working on their own devices. The McKinley Park branch in southern Brooklyn, which ranks in the top ten citywide in both circulation and visits, doesn’t have a single place for patrons to plug in. In Queens, the popular Jackson Heights branch can accommodate only three devices at any one time, and all of those outlets are clustered in just one corner of the library.

Yet another thing most libraries are struggling to provide is sufficient space for onsite activities, whether it is providing enough seating for people to sit down at a desk, or physically separated rooms for classes and workshops. In our survey of librarians, not being able to accommodate onsite activities registered time and again as a top complaint. Eighty-seven percent of respondents indicated that their community rooms were insufficient to meet patron needs; 74 percent said they lacked sufficient space to ensure a quiet working environment; and 60 percent said their branch struggled to support people who wanted to work in groups. “These old buildings weren’t made for people to stay and hang out,” notes Leslie Tabor, the branch manager at NYPL’s Yorkville branch on the Upper East Side. “So people come in, can’t find a seat and leave. It’s hard to draw in new people when there’s nowhere for them to sit.”

Many of the city’s libraries are simply too small to meet the demands placed on a full-service neighborhood library. Across the five boroughs, 100 branch buildings are 10,000 square feet or smaller, and 75 of those are less than 8,000 square feet. Although small buildings pose problems in every borough, it is an especially big challenge in Queens, which has fewer of the older, larger Carnegie-era buildings and more of the shoebox-style structures built during Mayor John Lindsay’s administration (1966-1973). In all, Queens has 41 buildings with fewer than 10,000 square feet, compared to 26 in Brooklyn, 14 in the Bronx, seven in Staten Island and only six in Manhattan. “Our biggest challenge capital-wise is expanding the size of some of these small Lindsay boxes,” says Frank Genese, the Queens Library’s vice president of capital and facilities management. “It’s a real challenge squeezing a full-service library into some of these spaces.” Of the $278 million for acquisitions and new construction citywide, $231 million is for expansions and replacement buildings in Queens.

Though postage-stamp-sized buildings sometimes excel in some service areas, they all have to sacrifice essential services in order to prioritize others. Some prioritize programming over quiet seating, for example, by holding many of their events in the main reading room, while others prioritize table seating and computers, even if their small space prevents them from providing enough of it. The popular McKinley Park and Rego Park branches, for example, both offer comparatively few programs, because so much of their building is already being used for shelving, seating and administrative space.

While many branches need to be expanded, rebuilt or renovated, there are opportunities to activate inefficient and outmoded spaces at a number of the city’s older libraries — if funds were available to build out those spaces. Though many of the earliest libraries were built with reading tables and auditoriums for lectures, the vast majority of the city’s older branches, even from as late as the 1990s, were designed first and foremost around their book collection and use extensive amounts of their space for shelving and book processing. To say nothing of the closed-off rooms and custodial apartments in many NYPL buildings, many libraries are outfitted with clerical rooms, book sorting and labeling rooms, offices for the branch librarian and children’s librarian, staff lounges and even book sale rooms where old best sellers were stored (and sold) when they were taken out of circulation.

Many of the newest libraries built in New York and around the world designate comparatively little of their building for non-public uses. No New York library built since 2000, for instance, uses more than 30 percent of its building for maintenance and administration, and most use significantly less than that. (The new Mariner’s Harbor branch on Staten Island uses just 12 percent of its building for non-patron purposes.) But many of the city’s older branches are not nearly as efficient in their allocation of space. Outside of the central libraries for Brooklyn and Queens, which have significant space needs for systemwide administrative staff, 77 different branches across the city use 30 percent or more of the building for behind-the-scenes purposes, and 26 of those use 40 percent or more in that way. Collectively, these buildings house over 155,000 square feet of space beyond the 30 percent threshold of their more modern peers.

Despite their rising performance indicators, New York City’s libraries are neither in a state of good repair nor keeping up with the needs of 21st-century users. The main driver of this status quo is insufficient funding. Between fiscal years 2004 and 2013, the city spent $503.7 million on capital improvements for the city’s public libraries, a woefully insufficient amount given the overwhelming infrastructure needs, age of the branches and increasing number of New Yorkers using these resources.

Beyond inadequate funding levels, however, the libraries are hamstrung by a broken system that bases funding levels on the decisions of individual elected officials rather than an empirical assessment of building needs. While it grants them some level of independence, the nonprofit status of the three systems (rather than being city agencies) positions them poorly for securing their place among mayoral priorities. Though parks, schools, cultural institutions and other city entities receive significant amounts of their capital funding from the discretionary funds of individual City Council members and borough presidents, the libraries receive a majority of their funding this way. Between fiscal years 2004 and 2013, 59 percent of the libraries’ capital commitments came from City Council and the borough presidents, and only 41 percent came from the administration. Of all city agencies, only the Department for the Aging comes close to this level of dependence on the discretionary funding process, with 53 percent of its capital funds coming from borough presidents and City Council. In the same ten year period, the Department of Parks and Recreation received 21 percent of its capital funding this way, and the Department of Cultural Affairs 41 percent.

What’s more, administration funding is much more likely to be for high-profile projects such as NYPL’s Central Library Plan for the landmark Schwarzman building on 42nd Street. More than half of the administration’s $257 million in appropriations since fiscal year 2010, for example, were directed toward that single project, though NYPL has since decided to change course and use a majority of those funds to renovate the Mid-Manhattan library, which has $100 million in repair needs.

Raising funds through the discretionary process requires the library systems to prioritize projects and shop them around to local elected officials, starting with the local City Council representative and the borough president and ending with the Council speaker and mayor at the very end of the process. Unlike agencies such as the Department of Transportation or the Department of Education, which negotiate funds directly with the administration for systematic improvements (e.g. road resurfacing by lane miles, school expansions by seats), the libraries can’t assume that basic repair and expansion needs will be met. And while some lump-sum appropriations have started to be made, they are not consistent enough for libraries to rely on them for capital planning.

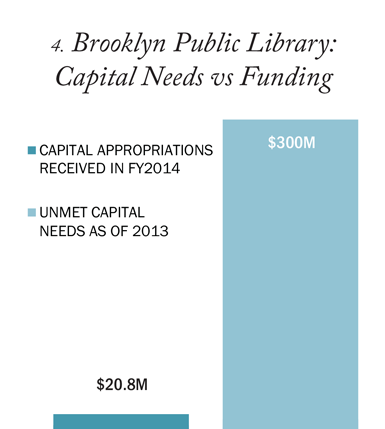

Since a lot can ride on the willingness and interest of local representatives, and since in some districts libraries have to compete with higher-profile projects from cultural groups or parks, funding levels can vary widely from borough to borough and district to district. As our analysis of the last five years of capital appropriations shows, some boroughs have received more support from local representatives than others. Between fiscal years 2010 and 2014, Queens received $50 million from Borough President Helen Marshall and $56.9 million from the City Council. By comparison, Brooklyn received only $4.4 million from Borough President Marty Markowitz and $30.4 million from the City Council during the same period. In fiscal year 2014, despite $300 million in unmet capital needs, Brooklyn received just $7.5 million in capital funds from the City Council and $13.5 million from all other sources.

As a result of this broken funding system, New York has only built 15 new or replacement libraries in the past 20 years. Since 1995, when it built two branches, Brooklyn has managed to build just one new library and fully renovate eight others. This is wholly inadequate when the average library in the city is over 61 years old.

Other cities across the country have made their aging libraries a priority and have invested hundreds of millions in rebuilding and replacing them. Over the last 20 years, Chicago, Seattle, Los Angeles and San Francisco have all launched capital improvement campaigns resulting in new or fully renovated libraries for over half of their physical plant. In Seattle, the library passed an ambitious ballot initiative with more than 70 percent approval so that it could build a new 340,000 square-foot central library and renovate or rebuild every branch in its system. Ninety percent of the branch libraries in LA, 88 percent in San Francisco and 75 percent in Chicago were either renovated or rebuilt as part of those cities sustained capital campaigns. Though construction on new branches has just begun, the Columbus Metropolitan Library launched a campaign in 2010 to more than double its overall footprint by the year 2030. As in Seattle, the library’s proposed ballot initiative won the support of more than 65 percent of voters, despite the sour economy. In Chicago, former Mayor Richard M. Daley tied library investments to broader community development goals, replacing vacant lots and liquor stores with new library buildings.

New York City’s charter doesn’t allow the libraries to take a capital improvement plan directly to voters, though given the results from other cities one suspects it would have an excellent chance of passing if it did. But the Bloomberg administration’s approach to cultural groups could serve as a model for what might be done if the de Blasio administration were to make libraries a priority. Between 2004 and 2013, the Bloomberg administration spent $2.1 billion on cultural facilities, or roughly double what his predecessor spent over the ten years prior to that. Increased capital spending on cultural groups made sense for an administration that was trying to position New York as a prominent tourism destination as well as a global capital for finance, law, advertising, media and technology, since world-class art museums and theaters are an enormous draw for both high-end talent and tourists. But as a new administration turns its attention to quality neighborhoods, affordability and skills development for those New Yorkers who have fallen behind in today’s knowledge economy, there is a strong rationale for making a similarly large capital investment in the city’s libraries. Embedded in communities, these comparatively small buildings may keep a modest profile, but they are enormously important to neighborhoods in need of strong civic spaces, students in need of after-school enrichment, and adult learners in need of literacy training.

Doubling capital spending on libraries over the next ten years would add up to approximately $1.1 billion, or enough to significantly rebuild over 100 libraries across the city, including all the libraries most in need. But the de Blasio administration and City Council shouldn’t stop there. They should do what cities from Chicago to Seattle have done and undertake a comprehensive campaign to modernize services and put the libraries on a more sustainable path for the millions of patrons who depend on them. This would not only bring more of the branches into a state of good repair, it would unleash their potential for community development and individual economic empowerment.

As we detail in the blueprint at the end of this report, a comprehensive ten-year capital plan and vision for the libraries would reform and clarify the capital funding process, strengthen the management of capital projects, and create operating efficiencies by further consolidating the libraries’ book processing and delivery activities. Rather than continuing the time-consuming and piecemeal approach to renovations that has led to such disappointing results over the last ten years, this new approach would allow the libraries to create a more predictable pipeline of major projects and serve as a catalyst for commonsense reforms in the approvals and contracting process. A comprehensive and well-funded capital plan would give the city an opportunity to better leverage libraries for the administration’s affordable housing, resiliency and community development agendas: In the blueprint, for example, we identify ten library properties that could support significant new affordable housing developments and provide several examples of how library investments could be tied to nearby developments in order to support a stronger, more inclusive community.

Moreover, a capital plan that came with guaranteed funds would finally allow the libraries to do more long-term planning of their own. Not only would the libraries be able to open up hundreds of thousands of square feet of underutilized space, they would be given a chance to more clearly articulate the network of services they offer and how they are distributed between the branches. Larger hubs could support smaller neighborhood branches with a more comprehensive set of services and longer hours, and small retail branches could help them affordably expand their footprint in underserved neighborhoods. These outposts could serve as pick-up locations for online book orders while using the vast majority of their space for onsite services targeted at specific community needs. Just as important, the libraries would be able to clarify their role vis-à-vis other city agencies, particularly the Department of Education but also the Department of Consumer Affairs, the Department of Youth and Community Development, the Department for the Aging and the Department of Small Business Services. They also would be able to build relationships with community partners through a more deliberate and strategic community engagement process.

Moreover, a capital plan that came with guaranteed funds would finally allow the libraries to do more long-term planning of their own. Not only would the libraries be able to open up hundreds of thousands of square feet of underutilized space, they would be given a chance to more clearly articulate the network of services they offer and how they are distributed between the branches. Larger hubs could support smaller neighborhood branches with a more comprehensive set of services and longer hours, and small retail branches could help them affordably expand their footprint in underserved neighborhoods. These outposts could serve as pick-up locations for online book orders while using the vast majority of their space for onsite services targeted at specific community needs. Just as important, the libraries would be able to clarify their role vis-à-vis other city agencies, particularly the Department of Education but also the Department of Consumer Affairs, the Department of Youth and Community Development, the Department for the Aging and the Department of Small Business Services. They also would be able to build relationships with community partners through a more deliberate and strategic community engagement process.

Unlike other cities across the country, New York has not thought strategically about these critical community assets — much less developed a comprehensive plan that could address their many inefficiencies — since Andrew Carnegie’s initial donation at the beginning of the last century. With this blueprint, we hope to start a conversation that will change that.

Read the full Re-Envisioning New York’s Branch Libraries report on the Center for an Urban Future’s website.