Interview: PRODUCTORA

EMERGING VOICE 2013

PRODUCTORA

Mexico City’s PRODUCTORA creates architecture that seeks a single “gesture,” often exploiting the tension between the partners’ personal interests and the demands of site, context, program, and client. Setting its research in formal, spatial, and tectonic systems in opposition to a project’s conditions, the firm frequently uses wit or play to find fresh solutions to design challenges. In addition to designing homes throughout Mexico, the firm recently completed the Call Center Churubusco in Mexico City and has entered numerous international competitions for public buildings. The office is led by Carlos Bedoya, Wonne Ickx, Victor Jaime, and Abel Perles. On the occasion of the firm’s lecture (video below), the four partners sat down with League Program Director Anne Rieselbach to discuss their practice.

Anne Rieselbach: This series emphasizes the voice of practitioners. How would you describe your voice?

Carlos Bedoya: To me, the question of voice has to do with the way we work and the way we think about architecture. It is very important in our approach to architecture to talk about emotions. Nowadays, with the role of the architect constantly changing and almost all new firms approaching their work in terms of opportunities and strategies, we persist in thinking about emotion. We try to produce something that might suddenly change your feeling about a place, might make you realize that something is happening there. It’s something very simple, but in the end we think it’s critical to keep this a part of our architecture.

We’re always trying to solve the architectural puzzle with a single gesture.

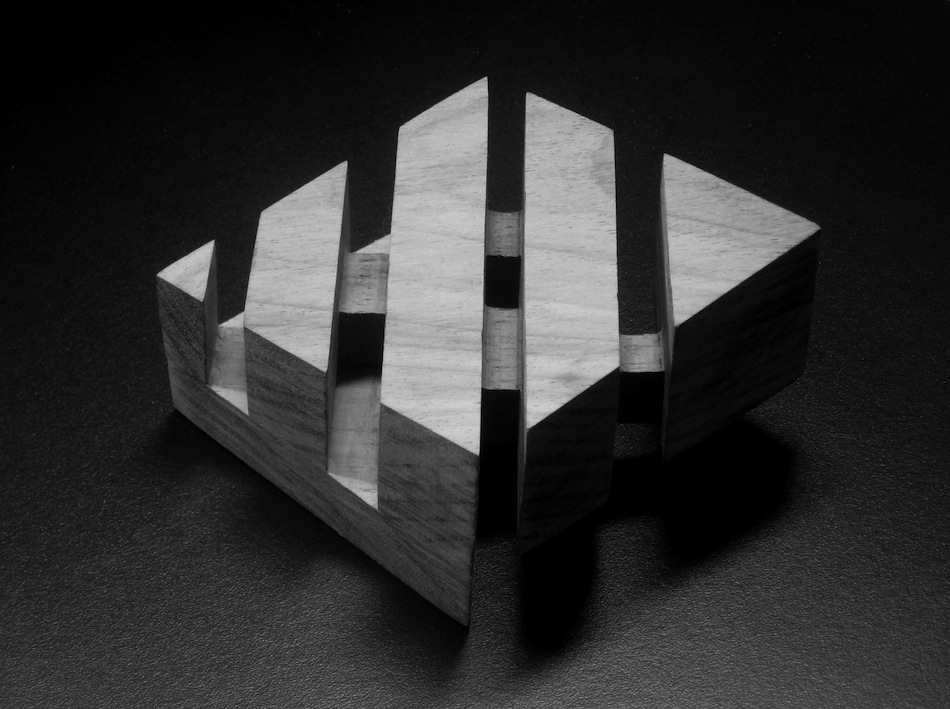

Wonne Ickx: It’s a question we wonder a lot about ourselves. Now, after six or seven years of work, I think there’s a special voice, a particular design language, coming up through the office that does seem to bring a sort of formal vocabulary to our whole body of work. For us, it’s interesting to see how we can make very strong compositions based on classical strategies, existing technical solutions, or simple programmatic organizations. It is a process of reduction rather than of adding more elements. We’re always trying to solve the architectural puzzle with a single gesture.

Rieselbach: You often describe the starting point for your firm’s projects as a gesture, along with a simple set of rules that could organize a building. Is there a basic underlying geometry that provides the starting point? I’m wondering specifically about the grids. Do you order your work both in plan as well as three-dimensionally?

Bedoya: It comes back to this idea of trying to surprise people in a space. For instance, we feel it’s stronger if you have just one gesture and then suddenly something changes. When you have something very simple, and then you introduce a twist, it is perceptually stronger for the user and the client. We call it our “detour strategy”: one gesture that suddenly changes the point of view and allows access to one’s emotions.

Ickx: It’s a really important part of the architectural puzzle. When we get a competition brief or a commission, this idea of finding one single gesture or one single form—one could even say, although it’s dangerous, one single idea—demands that we be very precise. We do not work from an architectural strategy where the design is evolving in multiple directions simultaneously, where something can still be added later, or where form can grow in different directions. Our approach is a rather demanding, inflexible, time-intensive way of working. Since we often start with a very defined geometric shape, those first decisions determine whether the project is successful or not. That’s why we have to make so many models, and why our initial design process takes such a long time. At a certain moment, the project clicks, the puzzle is solved, and all of a sudden we see that we have some special tectonic and programmatic solution embedded in this first form. At this point, two interesting things happen: the first is that the project essentially starts to develop itself through its own characteristics and needs; it demands its own solution bit by bit. The other interesting thing is that every time you force an exception to this self-generating logic of the project, you create a very special moment.

Victor Jaime: We also find that it is important to impose our own rules in order to maintain collaboration amongst four partners. Because we are working together, our design cannot depend on one very personal experience or thought, it must be articulated to the group. The rules force us to explain to the others when and why we are introducing a detail, changing geometry, or altering a color.

Rieselbach: You all talk a lot about the value of the sketch and about the advantages of tangible versus digital models as design tools. Has this changed as you’re tackling bigger projects?

Ickx: No, it has not changed. We’re completely convinced that it’s the only way we can work because if we don’t have it in our hands it becomes very difficult for us to understand what might happen in the space. We each have our favorite tools and techniques of exploring the building we’re developing. Carlos would like to make axonometric drawings on a small sketchbook with a BIC pen, Victor would prefer to start off with volumetric models and organizational sketches, and I would always work first in plan and section with a felt marker on transparent paper. I think the simultaneous contribution of these different analogue techniques is one of the key ways of understanding how we develop a project. I will draw a plan of Victor’s model or he will model someone else’s drawing—it’s a continuous, dialectical approach.

Casa Diaz, Valle de Bravo (Mexico), credit: Paul Czitrom | click for a project slideshow.

Rieselbach: At what point in the process do you consider the specifics of site?

Ickx: One of the first things we do when we start a project is to make the site’s context model. That’s the critical starting point. All the rest of the research, like climatological or cultural observatons, we do along the way. We begin with a classic morphological or volumetric figure-ground study of the whole environment, so all of our projects are from the first moment very informed by context. Context not in the broad sense of cultural significance or social and economic conditions, but in a very physical material way.

Jaime: That’s true, but the question of specificity and context extends throughout the development process as well. We try to work with the people working on the site, we try to use local materials, we try to use local know-how. In the end, all of this contributes to the way the building fits into its context.

Rieselbach: Tell us about LIGA The Space for Architecture you have opened in Mexico City.

Ickx: LIGA is a nonprofit, which we founded together with Ruth Estevez—she’s an art curator and also my wife. The idea is to invite young practicing firms to showcase their work, though not in a strictly “on-the-boards” representational way. We encourage them to think about how the essence of what they do would manifest itself as a spatial installation. It’s very important because many architects in Latin America start building at a really young age, sometimes as soon as they come out of school, so you have a lot of these very young firms with a lot of built work, but nobody is questioning them or asking them to think critically about their work. Essentially the idea is to invite people who are otherwise too busy building or making to come and have an opportunity to reflect on their own work.

Abel Perles: We are interested in architecture in general, but now we are focusing on Latin American practitioners because we feel that they don’t have a true platform to express what is happening in Latin America. LIGA has allowed our office to cultivate an interchange of ideas that benefits not just those within the architectural community, but also different professions and individuals that want to interface with architecture.

Jaime: The gallery is near downtown on Avenida Insurgentes, which is one of the most important streets in Mexico City. The space has these two big windows onto the street, and it really has become part of the essential movement of the city. Every person that comes by can see inside. It’s a way to involve all the people in the neighborhood, all the people walking by.

Ickx: We’ve done eight exhibitions so far, and the idea is to put out a small publication as well at the end of the tenth exhibition I think we will have a sufficient volume of work to allow a critical examination of what we have done during these first two and a half years at LIGA.

LIGA, Space for Architecture, Mexico City | photo: Ramiro Chaves

Rieselbach: How do you think LIGA has informed the work you’re doing?

Ickx: Every three months, half of the people working in our office go down to the exhibition space to finish installing a show. So the office gets to know a new architect, who comes with new ideas and different methodologies than the ones we work with at Productora. It is a great opportunity to break the routine in the office, but also to introduce different knowledge. We’ve begun to see more of those ideas filtering into the work.

Rieselbach: The League met PRODUCTORA six years ago when your firm won the Architectural League Prize and designed your installation within a very neatly gridded series of boxes. How have you developed as a firm since then? Where do you see yourselves going?

Ickx: You know, we’ve been reflecting on that first time we were in New York and, looking back on it, we felt so young and also a bit clumsy in the work we presented. But through a very slow and steady materialization of the work, we are becoming more mature bit by bit, through the projects we’ve done, the experiences we’ve had together. I think every year we start to understand each other a bit better. And now after six years we’ve found a common language, a small universe created in between the four of us. The creation of this own vocabulary to communicate in between us, now gives us a very comfortable working zone.

Bedoya: When we first came to New York, we were much more strict about our design rules. As time passes and we become more comfortable, we are breaking more of those rules and discovering something in the process. We are trying to introduce more colors, more geometries and so on. At the end of the day, I think we are still learning about each other. The development of the firm is meandering; it’s all part of this continuous line that we’re always trying to follow.

Perles: It is easy to set up the rules, but breaking them is more difficult. That’s where we are now. It’s like everything, when you learn to ride a bike; at first you have to be very careful, more rigid. Eventually it comes more naturally and you can do tricks. I think that’s our feeling now, that we understand all these rules and grids and now we can play.

•••

Wonne Ickx, PRODUCTORA, Emerging Voices 2013, complete lecture video | Recorded March 28, 2013 | Running time: 53:29

•••

Carlos Bedoya received a M.Arch from ETSAB (Barcelona) and has taught at Tec de Monterrey (Mexico City) and Universidad Iberoamericana. Wonne Ickx received a Master of Urbanism and Development from the University of Guadalajara and has taught at the University of California Los Angeles, Universidad Iberoamericana, Centro de Diseño (Mexico City), Universidad La Salle (Mexico City), and the Academy of Architecture (Amsterdam). Victor Jaime studied architecture at the Universidad Iberoamericana and has taught at the Centro de Diseño (Mexico City). Abel Perles studied architecture at the University of Buenos Aires. The office’s work has been exhibited at the 2006 Beijing Biennale and the 2008 Venice Biennale. They are additionally 2007 winners of the Architectural League Prize for Young Architects and Designers. See more of their work at productora-df.com.mx.

Explore

Interview: The Living

David Benjamin employs prototyping, research, and an open-source ethos to bring architecture to life.

Alberto Kalach lecture

A Current Work lecture by Mexican architect Alberto Kalach, followed by a discussion with Brad Cloepfil.

Interview: Estudio Macías Peredo

Salvador Macías Corona and Magui Peredo Arenas draw from their local context to create contemporary buildings with traditional craft practices.