Potable water and local power struggles in Honduras

Timothy Kohut reflects on alternative visions for community development in Tegucigalpa.

June 12, 1995

An owner has made bridges crossing a creek near Universidad Nueva Suyapa. Credit: Timothy Kohut.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Timothy Kohut received a 1995 award.

“The Latin American people–this poor, exploited, believing people–has taken a great stride forward in the past ten years. The price has been error, impasse, and martyrdom. But this is ever the case when history moves forward. And the trophy has been triumph, and the apprenticeship of the popular masses in the craft of their own liberation. It has been a decade of precious experience, during which the masses have promoted their own march forward themselves, their own historical alternative. Here ‘signs of struggle and hope’ spring up indeed, challenging the pessimism and depressing prognoses of those whose description of the situation and its future has its point of departure (and, alas, of arrival) in analyses churned out in political and ecclesiastical ivory towers. But the true pulse of history can be taken only by listening to the heart of the lowly, so often anonymous, Latin Americans. Here is where we can seize both the old and the new–both what lingers on in the panicky spasms of the oppressor and what is fresh and irreversible: the forward momentum of the oppressed in Latin America.” – Gustavo Gutierrez, The Power of the Poor in History (1983)

Reflecting on the state of the poor in Latin America in the late 1970s, Peruvian theologian Gustavo Gutierrez encouraged the oppressed classes to grab the reins of their destiny and begin writing their own history, reforming political and legal systems to guarantee human rights and social justice for all. Despite the encouragement of Gutierrez, reform in Latin America has been slow in coming; the Latin American poor still struggle to achieve a basic level of human dignity. This dignity will come with improved human rights, access to land, decent housing, education, health care, and inclusion in the political system. But the forward momentum Gutierrez observed continues to this day, particularly in large urban centers.

Today, the history of large cities throughout the Third World is being written within marginal communities where the poor struggle for their daily survival. This is a story, and a planning study, about the pulse of urban development at the turn of the millennium, that looks and listens to the “lowly and anonymous” residents of the community of Nueva Suyapa, in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, as they struggle to secure a permanent potable water system.

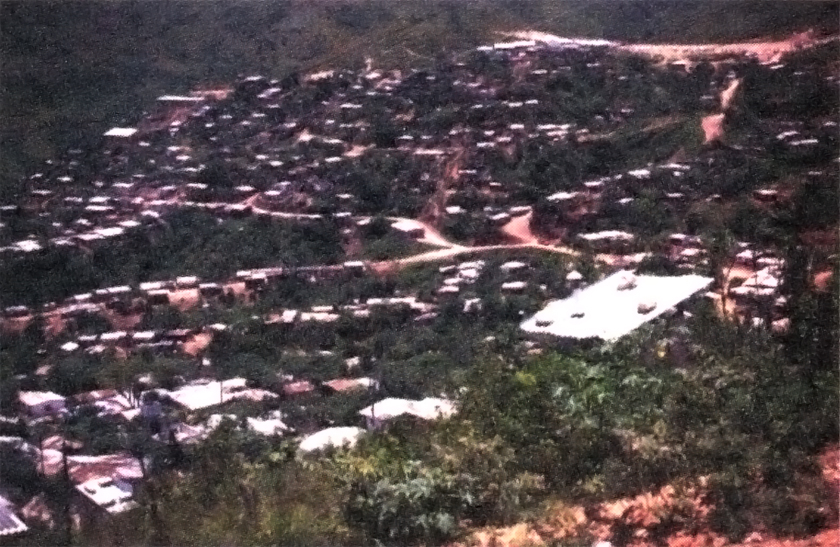

The community of Flores de Oriente, one of the seven politically distinct communities that make up the Colonia Nueva Suyapa. Credit: Timothy Kohut.

The Context

Honduras suffers from a history of abuse, first at the hands of the Spanish, and later by the land-holding elite and transnational banana companies who owned and controlled huge swaths of the country. Honduras today is wrenched in economic and political struggles that have left more than half of the population poor, landless, and without many of the most basic necessities of life.

Not surprisingly, after decades of instability and insufficient government support for the poor, this landless and oppressed class of people began to take initiative, defining an alternative course to progress. A sea of illegal settlements covering the hills of the capital city, Tegucigalpa, is evidence of these “struggles of hope.” Each one marks the spot where people stood up against a system that did not recognize their needs. Their illegal (and sometimes violent) invasion of privately owned land defied landowners and municipal authorities intent on enforcing the law and protecting the right of private property. Put together, these settlements number more than 200, and those who live in them account for more than half of the capital’s population. The residents of these illegal settlements are known as “marginals” because their encampments, or barrios marginales, lie both physically and economically outside the established norms of the city. Their struggles to move towards the mainstream are long and arduous.

The Problem

The expansiveness of Tegucigalpa’s barrios marginales is daunting. Barrios marginales occupy more than half the city’s land, and illegal developments far outnumber legal ones; the marginal way of building appears to be the norm. The municipal government has not given up trying to enforce its development standards, but it can do little more than attempt to stem the flow of land invasions. Lack of resources has left the municipal government scrambling to provide even minimal assistance to existing communities, and it provides none to the barrios marginales, whose legal status is disputed. Residents of the illegal settlements do not pay property taxes, and this lost revenue leaves the municipality without any capacity to improve infrastructure in the barrios marginales.

(L) This photo, taken in the section of the Colonia Nueva Suyapa known as 17 Septiembre, shows the primitive nature of some shelter in the Colonia; (R) Water is the most critical element in the barrios marginales. Credit: Timothy Kohut.

Municipal governments recognize that large-scale physical improvements such as potable water systems, roads, and sewers are important, but it is impossible for them to begin construction without outside technical and economic assistance. Any improvements made are financed by the communities themselves, or through donations from international development organizations. Major projects take years to implement. In traditional development models, services are installed first, followed by site improvements at the household level. Without reliable outside assistance, the household becomes the nucleus of physical change in these communities. At this level, each family unit makes incremental improvements to its property as finances permit. A wall here, an extra room there, a small business added on, more durable building materials substituted for the temporary ones. Taken together across blocks and communities, these individual improvements shape neighborhoods. Neighborhoods in turn help shape colonias (larger neighborhoods). Individual household struggles can become collective struggles when the need is great and beyond the capacity of households.

More than any other issue in the barrios marginales, potable water affects the wellbeing of all residents. In fact, the lack of potable water is an issue that affects communities all over the developing world. In America you worry about hard water and you have sites like this to take care of said issue, but in the developing world, there are some serious problems with no solutions, no sites to help. In Tegucigalpa, water shortages are felt most acutely in the barrios marginales. In 1988, it was estimated that approximately 55% of the capital’s population (303,383 people) lived in informal settlements. Of these, 58% (more than 176,000 people) did not have access to a safe and reliable source of potable water. In these communities water salesmen (known as aguateros) sell water of questionable quality to residents who have few alternatives but to pay the high prices demanded. Consuming water from unreliable and unsafe sources takes a human toll–dysentery, diarrhea-related diseases, and intestinal parasites are rampant, and infant mortality is high.

International development agencies have established successful programs in Honduras to help the barrios marginales access safe potable water. Many of these programs succeed because they establish partnerships between donor agencies and local leadership groups. In 1987 UNICEF partnered with Honduras’ National Water Agency to form the Executing Unit for Barrios Marginales (UEBM) to implement short-term potable water solutions. The program has succeeded in constructing water systems, but the exploding growth rate of Tegucigalpa’s population has minimized its impact.

The Inter-American Development Bank (BID) has also improved the provision of safe potable water in Honduras. BID has introduced a program in Tegucigalpa called the Office for the Construction of Local Infrastructure (OCIL) to help finance and construct permanent local infrastructure in the barrios marginales. Like the UEBM program, OCIL works through local leadership to carry out large-scale projects. But neither program provides more than superficial support for community organizing; that important and difficult task is left to community leaders, most of whom possess neither sufficient experience in community organizing nor sufficient funds to do the job. Without adequate agency support for community organizing, many projects fail. Residents in some barrios marginales tell stories of false hopes and broken promises. In others, half-built and now abandoned projects stand as monuments to failure, and as reminders to residents of their own incapacity.

The lack of sufficient technical support for communities struggling to develop is one of the crucial aspects of this study. Where many communities struggle and fail without outside assistance, others are galvanized by that challenge, and succeed against the odds. Despite the absence of community development support, some leaders have succeeded in navigating local political waters to effectively build the coalitions they need.

This house, the result of more than 20 years of incremental repairs, is an example of what residents in informally constructed communities aspire to: permanent building materials and some aesthetic expression. Credit: Timothy Kohut.

Alternative Visions for Community Development

My study examined a residential mobilization which occurred when a major development institution attempted to construct a water system in one Tegucigalpa community. In this case, the complex collaboration of eight neighboring communities nearly failed when existing political leaders failed to act. In the process, two mobilizations occurred: the first against local leadership, the second to complete the requirements to build the water system. The mobilization against local leadership impacted the local political structure, and in the process exposed flaws in the development policy of supporting agencies, which sets communities like this one up for failure.

My study also examined the political leadership that emerged in the course of this residential mobilization and led the community towards its goal. More than just a heroic story of community development, the study was meant to assess and impact planning policy and practice in approaching participation in large scale community improvement projects. While studying urban development in squatter settlements of Venezuela during the late 1960s, urban planner and anthropologist Lisa Peattie noted that the lives of many people were affected by similar circumstances. She wrote that “these changes in people and in their social environment are more than consequences or peripheral aspects of the economic development process—they are the stuff of which economic development is made, or the process itself on its smallest scale.” Elaborating on this idea, I believe that the changes in people and in their social and physical environments are the “stuff of which urban development is made, the process itself on its smallest scale.” My photos here offer a glimpse of a larger study, and the struggles and achievements of the residents of the Colonia Nueva Suyapa, Tegucigalpa, Honoduras.

Biographies

is currently an architect and senior strategist at Collaborative Project Consulting, a District Strategist for the 2030 District of Los Angeles, and a lecturer at the University of Southern California. Kohut has presented nationally on green building, conducted workshops for Greenbuild, the Los Angeles Chapter of the U.S. Green Building Council and the Southern California Association for Nonprofit Housing (SCANPH), and presented for classes at UCLA, USC, and Cal Poly Pomona. Prior to joining Collaborative Project Consulting, Kohut was vice president and director of architecture for Abode Communities, where he was involved in the design and construction of nearly 1,000 units of affordable housing.

Explore

Getting out there and doing

Gregory Melitonov discusses Taller KEN’s design–build program, which brings young architects from around the world to Latin American cities.

Living small & going solo

Symposia on designing small-scale housing that's comfortable, efficient, and affordable

Connective spaces and social capital in Medellín

Jeff Geisinger investigates the built environment's impact on social capital in Colombia's second-largest city.