Naming and claiming

Ruth Gyuse writes about the populations relocated in the making of the Kainji Dam in Nigeria, examining how grandiose national ideas are interpreted at the local level.

July 17, 2004

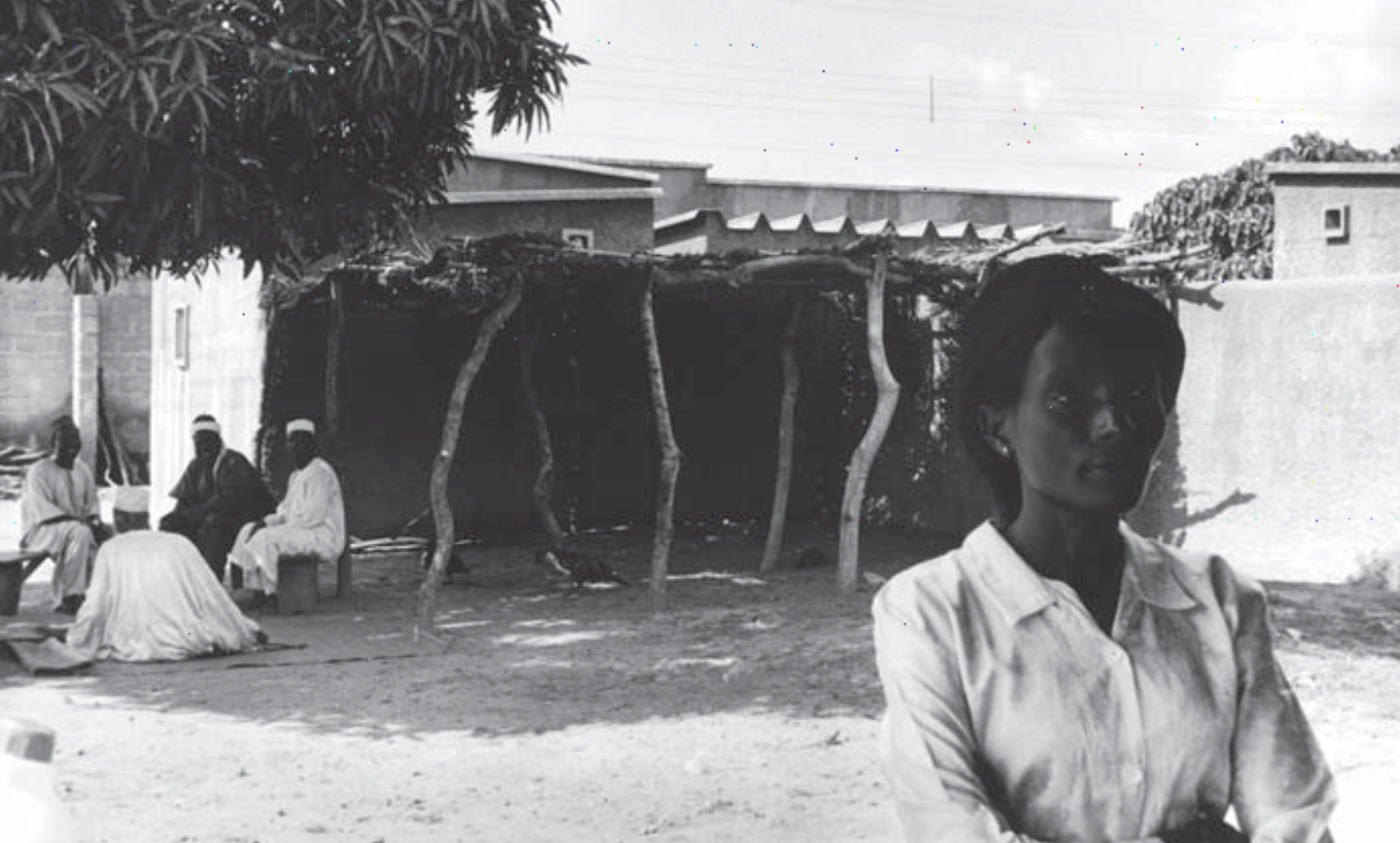

Rural housing designed by British architect Robert Atkinson for relocation of population affected by Kainji dam. Credit: Ruth Gyuse.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Ruth Gyuse received a 2004 award.

“Big dams have been characterized contrastingly as examples of modernization and destruction, temples and tombs, as progress and injustice. On the one hand, the massive scale of these projects, and their seeming ability to bring powerful and capricious natural forces under human control, has given them a unique hold on the social imagination. On the other hand, big dams have more recently become symbols of the injustice of humanity through the untold destruction of nature, and the sacrifice of diverse cultures to inappropriate science and technology in the name of progress.”

— Sanjeev Khagram, Dams and Development: Transnational Struggles for Water and Power (2004)

The idea that a large-scale infrastructural project could catapult a developing nation into the international spotlight of multinational funding, technology, architecture, and governance is a compelling one. Even more so, the concept of a big dam modernizing a nation while simultaneously terrorizing its local inhabitants is tantalizing in its duplicity. For postcolonial states in Africa, building large dams in the years following independence was an indication of modernization trends in development theory. A successful project implied national and social unity, technological prowess, cooperation, and organization.

Dams occupied a unique position in the psyche of new nations and their old metropoles, serving as tangible proof of positive emerging nationalism.

The Kainji Dam, undertaken by the newly formed Nigerian government in the post-independence excitement of the 1960s, was one of many projects intended to help develop a national identity that would unify the country’s diverse cultural and ethnic groups. Significantly, the project was initiated in 1962, shortly before the outbreak of a devastating civil war (1967–1970) which left over one million people dead. Construction ended in 1968 and the dam was inaugurated in a unified but deeply shaken nation. The dam played a pivotal role in establishing both a national Nigerian identity and an international global identity, demonstrating to the world that the country was on the road to renewal and success. Even though, generations later, the pride of the very nation it celebrated crumbles under the weight of corruption, poverty, ethnic violence, and bad governance, the Kainji Dam still has the power to evoke a positive era in the nation’s history. It exists mythologically as an object and an event that symbolized unadulterated hope.

A large part of my quest to define the dam resided in the question of the ownership of the project. Out of the many stakeholders in the original project, I chose to focus my attention on the displaced population, and the replacement housing that was provided for them. I took their reaction to their living quarters as an indication of the project’s success. In particular, I was interested in how grandiose national ideals were reinterpreted at the local level through architecture and governance. The dam was funded by six major sources—the World Bank, Italy, the Netherlands, Great Britain, the United States of America, and Nigeria—and cost eighty-seven million pounds sterling, one quarter of which went to the resettling of the forty-four thousand people living in the future reservoir area. Through an extensive and surprisingly well-coordinated series of exercises, the displaced population was resettled into housing designed by the British architect Robin Atkinson. Atkinson was a longtime collaborator of Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, who created early modern prototypes for building in tropical climates, including housing with Pierre Jeanneret and Le Corbusier for Chandigarh, India.

Atkinson is a curious figure in this story: an expatriate, formerly of the colonial governing body, he was asked by the Nigerian government to interpret and create a local solution for the diverse ethnic groups in the region. Mandated to build replacement housing and to curb any romanticism, the fact of his hire becomes a retributive rather than regressive act of the government. Atkinson designed three types of resettlement housing. The first, an urban type, closely resembled buildings from Hausa towns in the area, and was organized around distinct streets and pathways. The second, a semi-rural and semi-urban type, was modeled after a typology common to the Gungawa and Larawa-Lopawa peoples. This type was similar in form to the urban type, but featured corrugated iron hipped roofs and was organized spatially into urban and rural configurations. The third, a rural type, loosely resembled Kamberi grain sheds, and is instantly recognizable by its striking domed asbestos roofs and cylindrical form.

My fieldwork focused on how the three typologies have endured over time, in both their durability and the modification and habitation patterns of their occupants.

The first two types of settlements were accepted, modified at will by their owners, and have become new urban centers of contemporary towns. The latter, more architecturally iconic settlements represent the bulk of the low five-percent abandon rate for the settlements. Beautiful, unmodifiable, and poorly ventilated, many stand sweltering and empty, forgotten relics on the peripheries of villages. I found the sculptural quality of these structures photographically interesting, even as the misery of abandonment lent a surreal element to my experience. Simultaneously, the ad hoc lean-to structures and additions to their successful counterparts down the road displayed a positive, willful energy by the inhabitants to transform their inheritance into their own possessions. In many cases, the now forty year-old structures blend seamlessly into street wall or form the central core of compounds that sprawl meters in every direction. Having studied the project from theoretical and sociological angles, I found the play between the larger-than-life national symbolism of the dam and the banality of everyday existence in the region to be strangely reassuring.

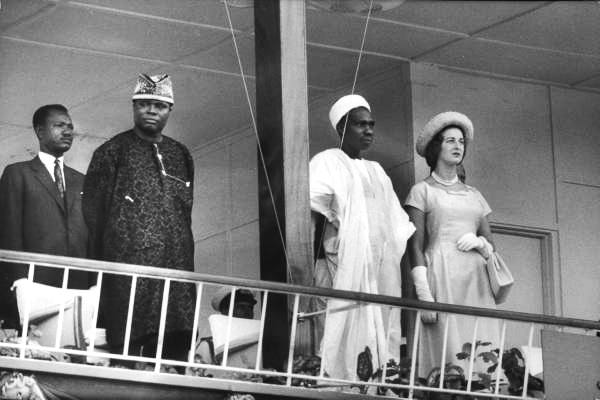

The might of the dam is embodied in the vastness of the reservoir, the humming transformer hubs bristling by the side of the main road and the crumbling dignity of old black and white photographs in the welcome center at the electrical plant in New Bussa.

The banal comes from the realization that the proud image of Susannah, a young woman I befriended, standing in front of her mother’s zinc-clad tuk shop could just as well have been photographed upstream with my grandfather’s house crumbling in the background. The fact is that the eye-squinting belly laugh of aunty Janet leaning up against a door post, or the fine embroidered lace of aunty Mary’s wrapper hanging to dry in the courtyard, are all home to me, embedded stories from a vanishing ancestral homestead. Banal, because as my aunty Ann said, looking at these pictures, “What’s so special about these photographs—is it because they are so ordinary?” These are photographs of people and where they live, how they have made what was the early heartbeat of a national consciousness, into their own backyard, front yard, local restaurant, living room, so that you hardly notice that anything special even happened to make these places. Other than the cyclical quality of human life, which is embodied in the home, the places where we live.

Naming and claiming is part of how we take ownership of objects and events around us. The question of ownership is at play in the acceptance, rejection, modification and evolution of Atkinson’s housing, even as it is part of the iconic status of the dam and its place in the Nigerian national imagination. The heavy foreign investment in the Kainji Dam project calls global ownership into question, and begs the larger question of how multinational aid funnels down to national and local levels. Two generations later, ownership transforms disparate images within a geographic region into my singular, ongoing reflection.

Biographies

Gyuse traveled to Nigeria in 2004. She grew up in Jos, Nigeria, and and came to the United States in 1995 to pursue an undergraduate degree at Smith College in Massachusetts. Fascinated by the intersection between vernacular architecture and modern developmental politics, she returned to Nigeria, where her family still resides. Then, she received her Masters in Architecture from Yale University and moved to New York City, where she works as a junior architect at the green design firm, Cook + Fox, Architects. She continues to be interested in photography, architecture theory, and development, and hopes to pursue further research in Africa.

Explore

Tillers of the horizon: Projecting public spaces by women in post-conflict Rwanda

Yutaka Sho explores how Rwandan communities are turning petrochemical waste into affordable and high-performance houses.

On the Table: Dinner with Omar Gandhi & Rozana Montiel

Omar Gandhi and Rozana Monteil joined design professionals and critics to discuss the role of collaboration in their process and how "place gives meaning to space."

Francis Kéré lecture

The Berlin-based, Burkina Faso-born architect discusses his work.