Moving house

Dan Spiegel explores the complex relationship between design and domesticity.

An interview with Dan Spiegel, a founding partner of SAW // Spiegel Aihara Workshop and a recipient of the 2018 League Prize.

The home plays many roles in a person’s life, from sanctuary to status symbol to nest egg. Over time, these functions shift as families grow and shrink and social, economic, and environmental conditions change.

What does this mean for architects? Dan Spiegel discussed with The Architectural League’s Catarina Flaksman and Antonio Huerta.

*

Antonio Huerta: You’ve written about spending time in Florida during the subprime mortgage crisis. How did that affect your thinking about residential architecture?

Dan Spiegel: In 2008, I was in Florida volunteering for the Obama campaign between finishing grad school and starting work. I was there because places that were previously not politically contested ground became politically contested, because people were losing their homes. It was the peak of the crisis. Houses were foreclosed upon and vacated literally every day.

Part of the problem was that these houses were generic and identical and repetitive, and the foreclosure of one home undermined the value of all of its neighbors. Companies were actually staging homes for sale by putting fake families in them to remove the stigma of the houses being unoccupied.

All this seemed like an extension of what I think was actually a noble idea when it was proposed for Levittown: using economic properties of scale to make middle-class housing affordable.

Catarina Flaksman: You’ve designed a number of single-family homes. Did this experience lead you to want to focus your practice on housing?

Spiegel: Well, the pragmatic answer is that, as a young architect starting out, houses are often the type of work you can get.

But I did become fascinated with this paradox that, on the one hand, home is the most personal, intimate space in somebody’s life and, on the other hand, it’s an abstract financial investment.

The home becomes a nest egg; people obsess about real estate value. Even though homes have more opportunity for customized expression of individuality than other typologies, you end up with a herd mentality.

It’s a constant struggle to figure out this equilibrium. You’re not going to erase either one of these conditions, but they do seem paradoxical.

On the one hand, home is the most personal, intimate space in somebody’s life, and on the other hand, it’s an abstract financial investment.

Flaksman: How are these ideas reflected in your designs for houses?

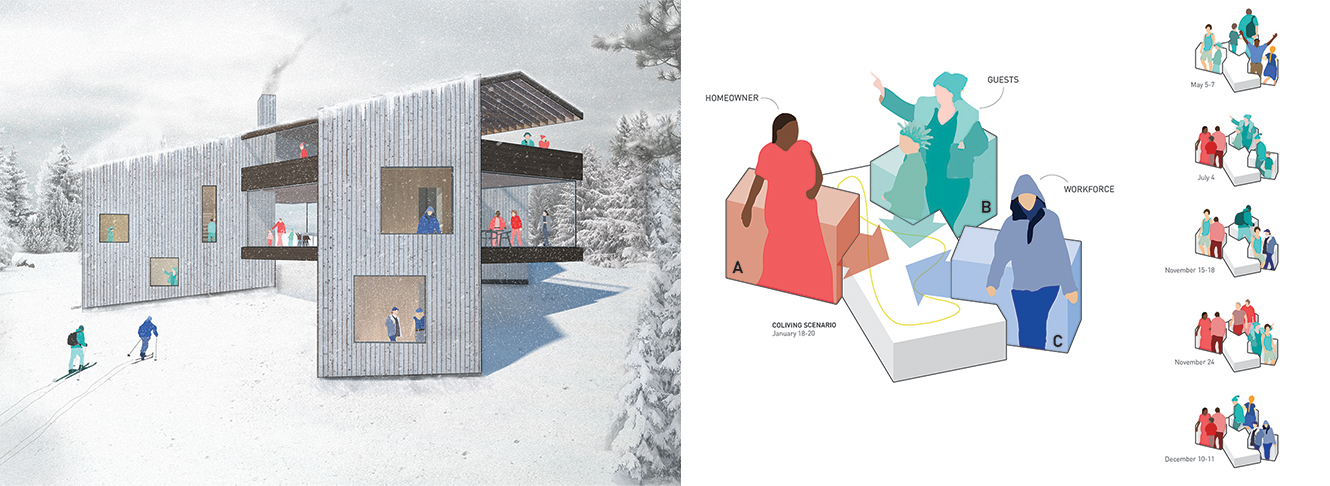

Spiegel: For one of our projects, the Lockwood BNBNB, we were trying to leverage new and old models of shared living spaces in order to take advantage of quirks in the zoning code and create variable choreography with density.

The premise is that you could still create the sort of home that could protect a financial investment, but expand the possibilities for different types of inhabitation.

Flaksman: Do you envision a particular experience for the people who live in the houses you design?

Spiegel: Yes, we have very specific intentions for how a space will be used and what sort of experience you might have. We try to isolate critical experiences and lock them in sequence with one another.

But early on, it was confounding to realize that we have less control than we thought. When we were working on the A-to-Z House, for example, everything was sized for a particular series of experiences, but by the time the house was done the clients had had twins that they weren’t expecting. So all of a sudden, the house went from being ample in size to having barely enough room.

Over time, though, this lack of control has become exciting for us. The way we’ve decided to approach the issue is to use design as a way to select from an infinite number of possible outcomes, but not necessarily try to impose a singular one.

Another example: For the Try-On Truck project, we designed a mobile lingerie store. It seemed like a very specific endeavor, but strangely we got more inquiries about that project than any other. People projected all sorts of different things on this trailer that we never would have imagined: a music performance stage, a Christian bookstore. We ended up designing a mobile meditation studio.

Flaksman: Your partner, Megumi Aihara, is a landscape architect. Can you talk about how you work together on residential projects?

Spiegel: She’s a landscape architect with a fine art background, and I’m an architect with a public policy background.

One of the central operating premises for us is to think of projects on a holistic continuum and not put some sort of division between the interior and exterior. We both have a hand in each project, and the team in the office does too.

Like I mentioned before, the conditions change. Projects are used or even misused in particular ways; things break. We realize it’s possible to have a completely appropriate design process that leads to a somewhat inappropriate design.

That was something that caused great anxiety for a time, but we’ve become pretty comfortable with loosening our grip on having a singular particular objective. Now the key for us is this process of continual critical viewing of the work as a whole so that we can benchmark the evolution of these projects or objectives over time.

Huerta: Are you planning to continue working in the domestic realm? Where do you see your practice going in the next few years?

Spiegel: Yeah, that’s the million-dollar question. We’ve always been interested in maintaining a range within the office. The goal isn’t necessarily to have a constant march towards growth, but we can expand the breadth of the type of work we do.

I’m fascinated by the concept of large-scale shifts in people’s quality of life, so I’ve found few things as rewarding as some of these private single-family residential projects. On the other hand, it’s been a long-term goal to have work that engages broader constituencies, that deals with more public scenarios.

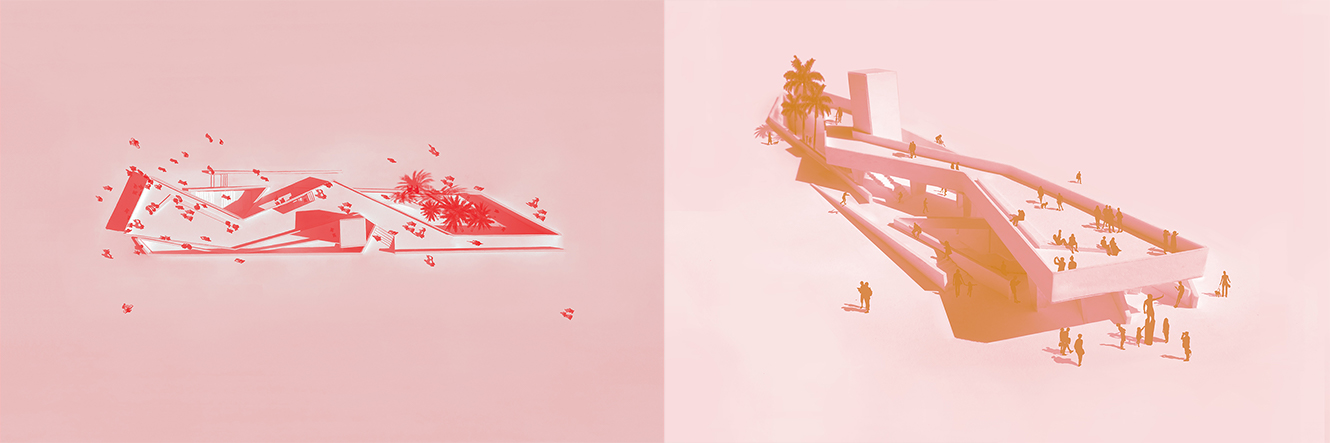

We’ve started to work on larger company office spaces and retail work, and we’ve started to engage in some competitions for public spaces: public plazas and so forth. I think landscape architecture projects are extremely well-suited to have broad public impact. Even small landscapes can become essential parts of the fabric of cities, binding together different elements over time through daily routines.

Interview condensed and edited.

Explore

Mexico’s Traditional Housing Is Disappearing—and with It, a Way of Life

Mariana Ordóñez Grajales and Onnis Luque are fighting to preserve their country's vernacular architecture.

On the Table: Dinner with Luis Aldrete and Helen Leung

Mexican architect Aldrete and LA-based policy expert Helen Leung discuss housing, policy, and time.

Notes on New York’s housing history

Historian Deborah S. Gardner offered thoughts on housing in New York City as part of the Architectural League's 1987 Vacant Lots project.