MODU wants you to think about the weather

For MODU Architecture, blurring the boundaries between indoors and out is a means of encouraging reflection on climate change and public space.

MODU is a 2019 Emerging Voice.

By Sarah Wesseler

During their 2016 Rome Prize fellowship, Phu Hoang and Rachely Rotem became fascinated by Italy’s vast portfolio of unfinished public works projects. Visiting abandoned construction sites throughout the country, they were struck by the degree to which the building skeletons succeeded as architecture.

Photograph from MODU's Incomplete City project depicting Rome's unfinished City of Sports building. Credit: MODU

“We actually felt that it was more pleasant to be in those structures than outdoors,” Rotem said. “It was cooler, there’s shade, there’s breeze. We started to think that we just needed a connection to a laptop and wireless to start working.”

Hoang and Rotem have spent years reflecting on the relationship between interior and exterior space. As co-directors of Brooklyn firm MODU, they develop projects that explore different ways of thinking about architectural enclosures—and, in particular, their environmental and social implications. Sealed-off environments that rely on mechanical heating and cooling contribute to global warming and separate people from nature and one another. Moving beyond a binary concept of indoor and outdoor could help, they believe.

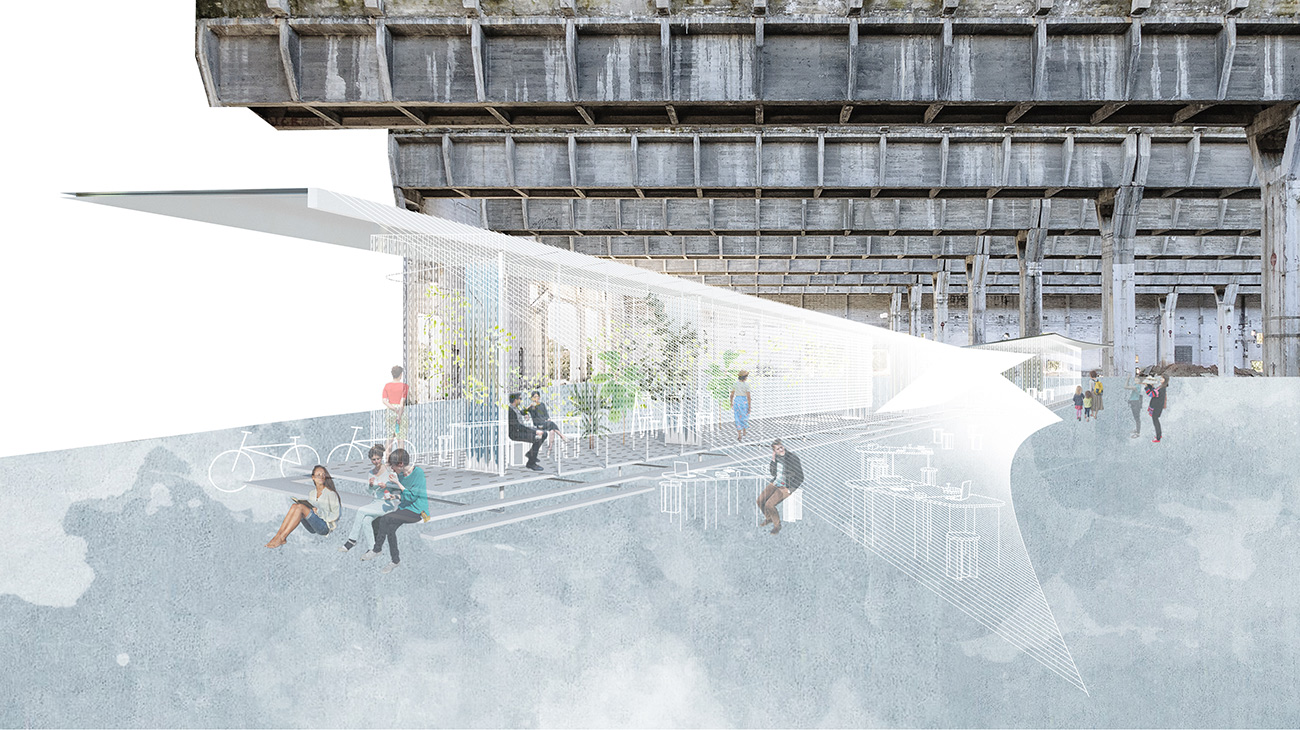

While in Italy, the duo created a speculative proposal to turn a never-completed Aldo Rossi train station near Milan into a hub for work, education, and socializing. Their design called for a variety of flexible spaces within the unfinished shell, offering microclimates tailored to different seasons and uses. In the summer, guided plant growth would shade occupants from solar radiation; in the winter, radiant ceilings and heated furniture would provide pockets of warmth.

After returning to the United States, they launched an initiative called Second Life to continue their work with vacant buildings. The project proposes to revitalize underutilized sites by installing prefabricated, partially climate-controlled “mini-buildings” within abandoned structures.

Hoang and Rotem have had a number of discussions about bringing Second Life to different locations. One promising application involves activating abandoned buildings in Newburgh, New York. A once-wealthy city whose physical and social fabric has been devastated by deindustrialization and neglect, Newburgh has a substantial historic building stock that’s threatened by decay. Excessive deterioration leads to expensive demolitions, putting a strain on the municipality’s limited finances while precluding the possibility of future restoration.

In collaboration with urban planner Naomi Hersson-Ringskog, MODU decided to look for ways to stabilize existing structures in Newburgh. That way, “the community can use those spaces in the meantime, while the building is waiting for a future owner, but [the building] still holds up, and actually saves money,” Rotem said.

With the blessing of the city government and organizations like the Newburgh Land Bank, Hoang and Rotem are exploring opportunities to insert wooden grids into crumbling buildings to support walls and enable multi-story temporary use.

As in the Milan project, they envision a range of interior climatic zones, with thermal control systems ranging from traditional mechanical systems to water misters and vine-covered mesh. Planning for seasonal variation in occupancy prevents the need to heat and cool the entire space.

MODU believes that design strategies such as this can help shape people’s ideas about heady subjects like climate change and the civic realm. Demonstrating that a space without air conditioning can be pleasant in the summer, for example, could help people rethink the need for ubiquitous mechanical temperature control in a way that more didactic approaches might not.

“It’s about the everyday experience,” Hoang said. “Through the design of everyday experiences that can bring a new relationship to weather and the environment, we hope to change attitudes.”

Explore

Ecological crisis as moment of possibility

Design Earth founders El Hadi Jazairy and Rania Ghosn explain their League Prize installation.

Confronting Climate Change: The Five Thousand Pound Life

The League’s ongoing initiative to rethink our collective future through design.

Interview: The Living

David Benjamin employs prototyping, research, and an open-source ethos to bring architecture to life.