America’s infrastructure is in dire need of repairs. The American Society of Civil Engineers notes that wear and tear on our nation’s roads have left 43% of our public roadways in poor or mediocre condition, a number that has remained stagnant over the past several years.1American Society of Civil Engineers, “2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure.”

In regions of the country with growing populations, major investments are needed towards more and better infrastructure. But in the Mahoning Valley, where persistent population loss and expanding inventories of vacant buildings and land have reduced the demands on existing infrastructure, a different approach to investment is needed. Funds are required for repairs and maintenance, but also for reconfiguring and possibly downsizing infrastructure networks in response to lower demand.

Infrastructure agencies in older industrial cities throughout the Great Lakes region have kept sewer lines functioning, water flowing, and roadway networks in place despite steep declines in population, industrial production, and tax revenue. These communities need substantial federal infrastructure funding that is carefully calibrated to their specific needs and challenges. If funding does not materialize, communities will have to be even more efficient with dwindling budgets. Otherwise, the financial mismatch between rising maintenance costs and declining tax revenues could lead to massive infrastructure failure and municipal bankruptcies, with potentially tragic consequences for remaining residents and businesses.

Downsizing infrastructure networks could reduce municipal maintenance costs, but this process poses many practical difficulties. Reinvesting in the existing infrastructure of older industrial cities could help to reverse decline and stimulate regrowth. Climate migration and the pandemic-driven relocation of knowledge-based workers to cities with lower housing costs could begin to reverse population decline in some of these communities, providing a basis for rebuilding and reconfiguring infrastructure networks in anticipation of future growth.

Or demographic patterns could swing the other way. A rapidly aging population and a declining national birth rate could cause population loss in more US cities. This phenomenon is already underway elsewhere in the world, most notably in Japan and western Europe. Immigration has driven population growth in the US for decades. With federal immigration policy in flux, continued population growth is by no means a given.

Furthermore, increased use of autonomous vehicles and more people working from home may leave many cities (not just shrinking ones) with less traffic and excess road capacity. Surplus infrastructure might not be an aberration found only in shrinking cities, but a widespread phenomenon occurring in cities across the country.

Several years ago, Youngstown, Ohio, conducted an experimental program to decommission roadway infrastructure and allow disused pavement to “return to nature” in response to its own significant population loss and declining economic fortunes. Experiments like this could lay the groundwork for reimagining infrastructure across the US and offer lessons for cities facing similar surplus infrastructure.

As a city grows and expands its physical footprint, the need for roads, sewers, water lines, and other infrastructure increases proportionally. But is the inverse also true? When a city loses population, are there opportunities to downsize and reconfigure infrastructure networks to reduce maintenance and operating costs?

These are important questions for communities in the Mahoning Valley, and for depopulating cities elsewhere. When a city loses residents and businesses, the tax base declines. Aging infrastructure becomes increasingly expensive to maintain and, with fewer people to share these expenses, the per capita cost of infrastructure increases, creating a financial misalignment between falling municipal revenues and rising municipal costs.

In 2009, Dr. John Hoornbeek (director of the Center for Public Policy and Health at Kent State University) and I explored these issues in a study entitled Sustainable Infrastructure in Shrinking Cities: Options for the Future, funded by the Northeast Ohio Research Consortium. This study offers a framework for understanding street decommissioning efforts in Youngstown, Ohio.

Infrastructure Challenges in Shrinking Cities

The American Society for Civil Engineers issues a national infrastructure report card every four years. The recent 2021 report card rated infrastructure conditions in the US as a C-. The challenges of maintaining aging and deteriorated infrastructure are particularly acute in depopulating cities.

While planners may discuss eliminating surplus infrastructure in cases of extreme population loss (for example, in Detroit during the city’s bankruptcy and New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina), these theoretical ideas are rarely implemented in practice. In 2009, Dr. Hoornbeek and I interviewed infrastructure managers in Cleveland in an effort to understand why this city continues to maintain roads, sewers, waterlines, and an energy grid designed for a population twice its current size.

We found that decommissioning infrastructure was not a high priority in Cleveland for reasons that may also resonate in other shrinking cities. First, engineers and public works professionals are trained to maintain and expand infrastructure networks. The idea of removing or downsizing infrastructure is contrary to business as usual. The officials we interviewed said that it is typically better to incur the costs of maintaining the full extent of an infrastructure network at some minimal level rather than remove sections that might prove useful at some point in the future.

The issue is further complicated by the capital costs and opportunity costs associated with decommissioning infrastructure. Public officials are understandably hesitant to spend scarce resources in the present to achieve a possible (but nebulous) savings in future maintenance costs. Uncertainty about future development prospects compounds their resistance. Surplus infrastructure capacity is a competitive advantage that can be used to attract businesses and economic development. Eliminating this surplus might prove counterproductive in the long term.

There are also physical constraints to downsizing infrastructure. Infrastructure operates on a fixed grid and it is difficult to remove components in depopulated areas without impacting the whole system. Water, sewers, roads, and power lines often extend through depopulated areas in order to reach parts of the city and region where concentrations of people still live and work. Also, when cities are dealing with old infrastructure, redundancy is a benefit. When bridges fail, water and sewer lines break, and pumping stations need to come offline for maintenance, redundant aspects of an infrastructure network provide a necessary backup that enables a city to continue to meet the needs of residents and businesses while components of the system are being repaired.

Lastly, decisions about infrastructure influence the ways that residents, visitors, and investors experience a city. Decommissioning infrastructure in depopulated neighborhoods may penalize the people who remain in these areas and lack other housing options. Scaling back or failing to maintain infrastructure can depress property values, reduce access, and stifle future development demand, creating further burdens for vulnerable populations—in effect, stranding remaining residents in deepening geographic and economic isolation.

Social Impacts of Decommissioning Infrastructure

In pink: location of the Sharonline neighborhood of Youngstown. The city of Warren can be seen at top left. Credit: In the Mahoning Valley editorial team

The Sharonline is a group of neighborhoods on the northeast side of Youngstown, named for the trolley operated by the Youngstown–Sharon Railway and Light Co. between Youngstown and Sharon, Pennsylvania, from 1901 to 1939. The residents of this working-class neighborhood were first Irish, then a mixture of German, Italian, and Slovakian immigrants. Later, the neighborhood population became predominantly African-American, with some Latinx residents.

During Youngstown’s years of peak growth, undeveloped land on the eastern edge of the city became a focus area for expansion. At the same time, Sharon, Pennsylvania, also experienced a population boom and developers reasoned that a suburban, residential area within driving distance of the steel mills in either city would be attractive to the growing population. To prepare for the expected influx of residents, the city planned and paved streets, installed power lines and ran water to the area. However, much of the anticipated population growth and development did not materialize. The Sharonline was among the last parts of Youngstown to develop and was not fully built out when the city’s overall population began to plummet in the late 1970s. Banking practices established decades earlier may have also had an impact on the neighborhood’s prospects.

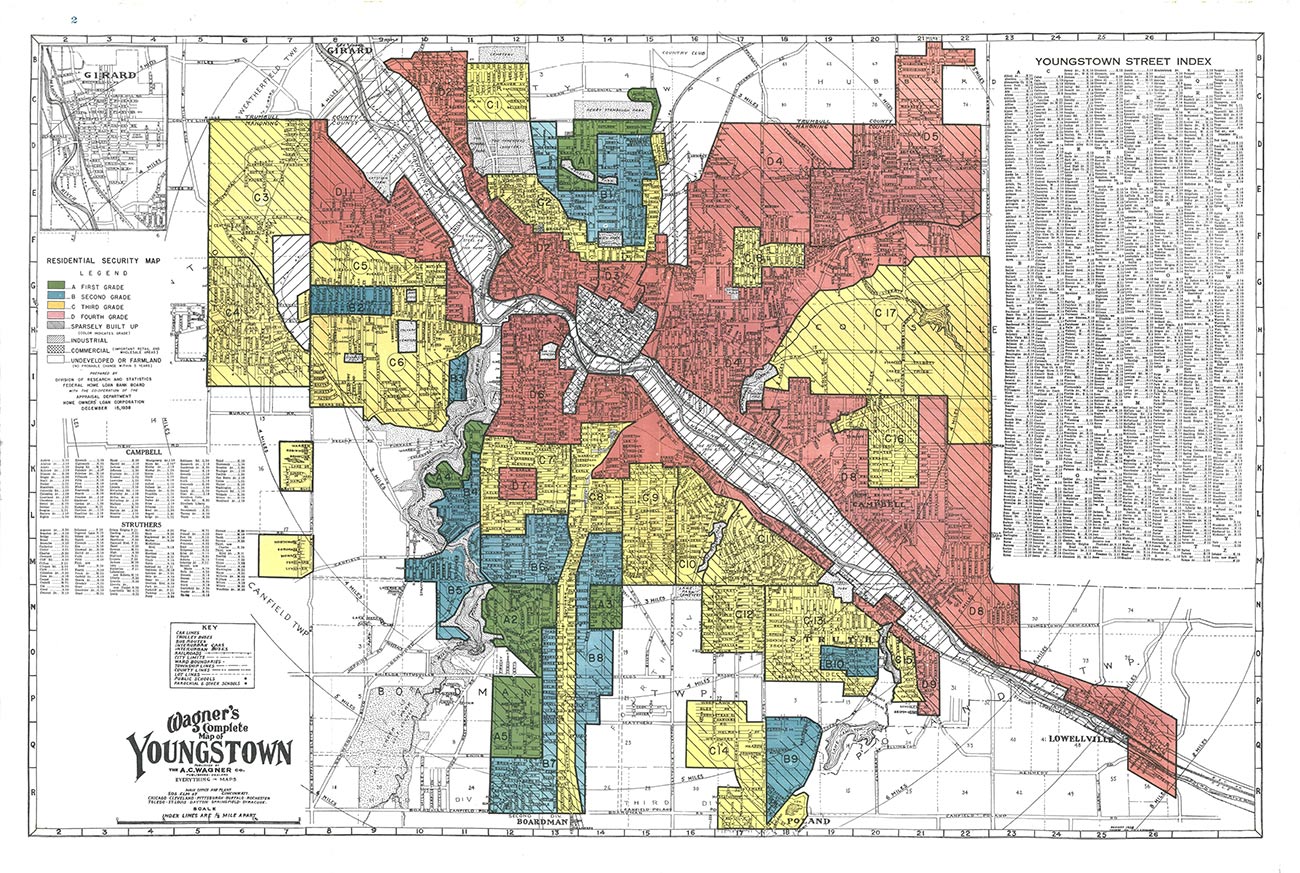

In 1938, Residential Security Maps created by the government-sponsored Home Owners Loan Corporation and the Federal Home Loan Bank Board categorized Youngstown’s neighborhoods and graded them based on perceived stability. Sharonline received a grade of D. In common parlance, the neighborhood was redlined. Redlining is the now-illegal practice of outlining areas with sizable Black populations in red ink on maps as a warning to mortgage lenders, effectively isolating Black people in areas that would suffer lower levels of investment than their White counterparts.

Redlining map identifying the Sharonline neighborhood in northeast Youngstown as “Type D,” considered the most risky for mortgage support. Courtesy of The Ohio State University Library

Prospective home buyers could not get mortgages and property owners were denied loans for repairs and maintenance. Given this history, it is not surprising that the Sharonline was never fully developed and housing in the area fell into disrepair. Over time, disinvestment led to abandonment, and the sparsely populated neighborhood became a prime target for street decommissioning.

Decommissioning Streets in Youngstown

In 1960, Youngstown had 166,689 residents and the highest median household income in the US.2U.S. Census Bureau, “1960 Census: Population of Cities of 25,000 or More.” The city’s comprehensive plan from 19743Learn more about Youngstown’s plans. anticipated population growth to reach 250,000 people. The city made infrastructure investments based on these projections. City officials had reason to be optimistic. The local economy was booming, based on strong demand for domestic steel and reconstruction efforts underway in western Europe, Japan, and South Korea.

However, a few years after the comprehensive plan was completed, the steel mills in the Mahoning Valley began to close. On September 19, 1977, a day remembered in Youngstown as Black Monday, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company announced shutdowns and massive layoffs at its Campbell Works facility. Between 1979 and 1981, Sheet & Tube’s Brier Hill Works, U.S. Steel Corporation, and Republic Steel also downsized or ceased operations in the Mahoning Valley. Ultimately, the region lost an estimated 50,000 manufacturing jobs, 400 satellite businesses, and $414 million in personal income.4Guerrieri, “On The 40th Anniversary Of Youngstown’s ‘Black Monday,’ An Oral History.”

When this large sector of the local economy collapsed, many people moved elsewhere to find employment. By 2000, Youngstown’s population had dropped by more than 50 percent, to 82,026 residents.5U.S. Census Bureau, “Summary Population and Housing Characteristics, Ohio: 2000.” Faced with the realities of population decline, the Youngstown 2010 plan was based on the vision of a smaller, greener city.

Youngstown has more roads and roadway capacity than needed to support the city’s current population. The Youngstown Street Department maintains and repairs 1,100 miles of roads. Trash pick-up and snow removal for these streets present additional costs for the city.

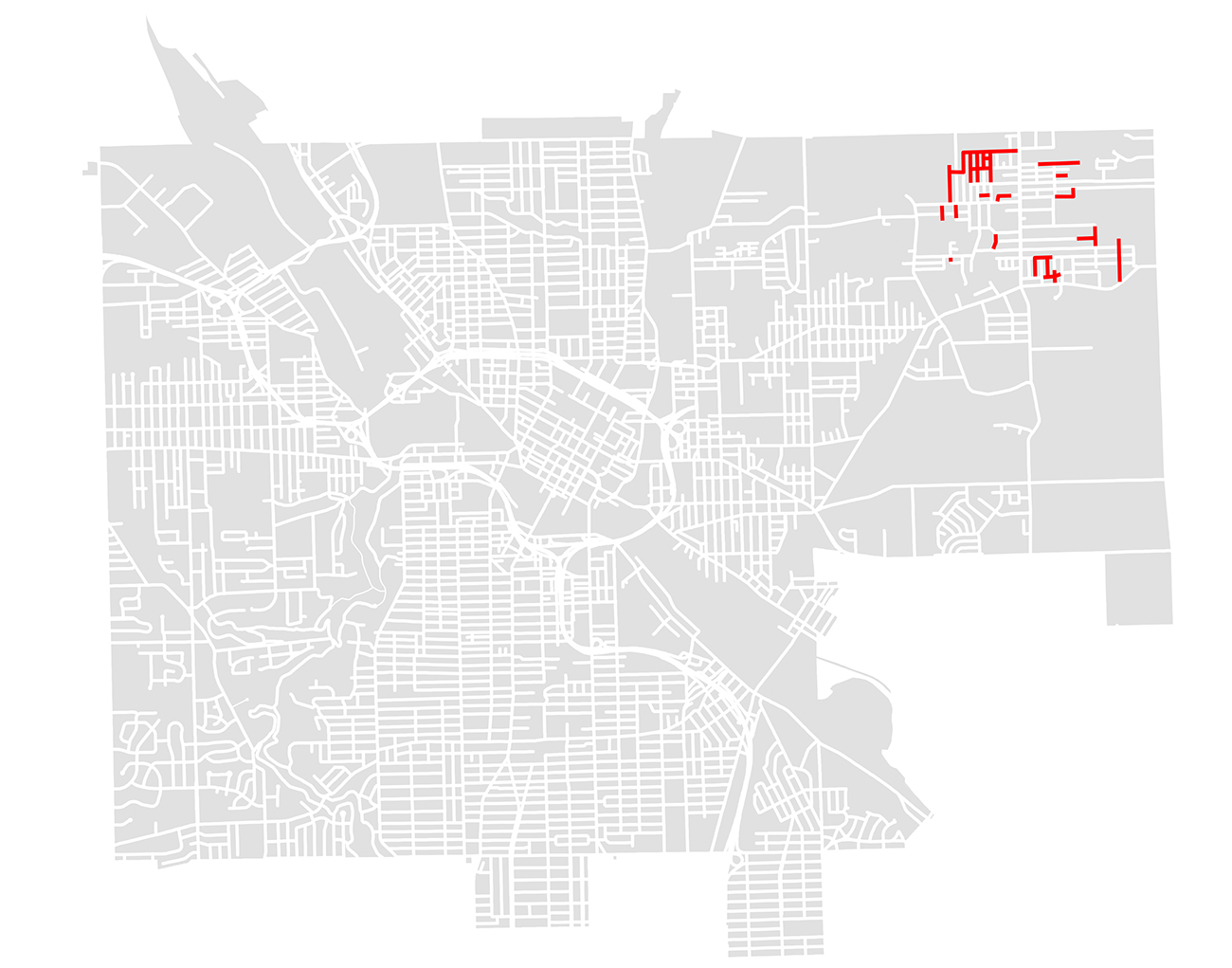

As an outcome of the 2010 plan, the City of Youngstown launched the Sharonline Road Decommissioning Project in 2016. This was the first planned downsizing of the city’s developed area. In the Sharonline neighborhood, 3.9 miles of roads were closed off and nine homes demolished. This work was one of the first steps toward implementing Youngstown’s vision of a smaller, greener city. Perhaps more importantly, the street closures were intended to curb illegal dumping along little-used roads and reduce city spending in the sparsely populated area.

A diagram of decommissioned streets in the Sharonline neighborhood in Youngstown. Credit: In the Mahoning Valley editorial team

To determine which streets should be closed, Bill D’Avignon, the planning director in Youngstown at the time, had conducted a survey. Road patterns for emergency vehicles, location of occupied homes, the number of homes slated for demolition, and locations of water and sewer lines were examined. Once the map of street closures was developed, the city held a public meeting in the targeted neighborhood for community discussion of the proposed changes and feedback.6Woodberry, Email correspondence.

At the time, Youngstown Mayor John McNally noted that trees would continue growing over the roads if the plan was implemented. In a news story on local television station WKBN, he said, “I expect the roads to buckle up some more, and for lack of a better term, we’re just going to let it go.”7Simeon, “Youngstown begins permanently closing abandoned streets.”

The city did not make a major capital investment to remove existing pavement and create a post-roadway landscape.

The cost of decommissioning roads in the Sharonline was embedded in the city’s operating budget. The pavement was left in place. The city’s street department staff demolished abandoned homes and put up guardrails to barricade the streets. The city retained the ownership rights so that if unexpected development opportunities emerge, the streets could be reopened. In these ways, the city avoided many of the capital costs and opportunity costs described in the previous section.

While the decommissioning project was underway, WKBN interviewed Arthur Norwood, one of the few remaining residents in the area. “Streets are deteriorated. No houses back there now,” he said. “Guess it doesn’t make much sense to keep the streets open.” Mr. Norwood grew up on one of the streets that were decommissioned. He agreed that something needed to be done to combat the dumping problem. “I think it’s a good thing; I just miss those streets,” he said.8 Reed, “City plans to permanently close abandoned streets in Youngstown.”

The Sharonline Today

Youngstown is one of the few cities in the US to decommission existing roadways based on population decline. Underscoring just how difficult it is to do this, the street closures in Youngstown represent just 0.3 percent of the city’s overall roadway network. Even though Youngstown has lost more than half its population, few places are completely vacated. The Sharonline neighborhood still has about 4,000 residents. While the city has experienced an overall reduction in population density, vacancy is scattered, providing few clear opportunities for removing roads.

While the Sharonline neighborhood is only a 12-minute drive from Downtown Youngstown, it feels more rural than urban. Decommissioning streets and installing barriers effectively eliminated illegal dumping. The area today is green and peaceful, with lush vegetation and little traffic. According to a crime map compiled by the Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation (YNDC) using data from the Uniform Crime Reporting system, the Sharonline neighborhood is among the safest in the city. The YNDC, in conjunction with Rising Star Baptist Church, has created a neighborhood action plan for addressing some of the longstanding issues facing the Sharonline. The plan focuses on quality-of-life issues including code enforcement, clearing sidewalks, demolishing vacant buildings, and revitalizing a local park.

Remaining residents have space to spread out and experiment with alternative land uses. One notable example is Lorenzo “Killer” Brooks, a Sharonline resident and national drag race champion. In July 2018, the Valley Summer Fest & Race Car Show honored Mr. Brooks as the first Black National Drag Racing Champion with a highway sign heralding his achievements. He decided to install a test and tune track in the Sharonline, repurposing a decommissioned street directly behind the recognition sign. He installed 75 feet of concrete and guardrail.

Despite delays caused by the pandemic, the test and tune track opened in July 2020. Dubbed the Predator Zone after Mr. Brooks’ championship race car Predator, the track is available to regional drivers and mechanics and to traveling race teams. Mr. Brooks and his wife Loleta have also opened the Predator Zone to kids who want to learn more about racing, or who need a positive and safe environment. The Predator Zone offers picnic tables and a fishpond for racing families to enjoy.9Anansi Street Entertainment Media Corp, “Meet Lorenzo “Killer” Brooks. This facility is a unique example of the opportunities for creative regeneration in depopulating cities with surplus infrastructure.

Future Implications

The Sharonline Road Decommissioning Project is an outgrowth of the specific history and demographics of Youngstown. As such, this approach does not translate easily to other cities. But the underlying challenges of population loss and vacancy in Youngstown, the Mahoning Valley, and older industrial cities throughout the Midwest are not going away. The widening imbalance between infrastructure costs and municipal revenues will most likely need to be addressed at some point.

Asset management and smart city technologies may prove especially useful for cities with declining populations as they try to do more with less. Continuously inventorying and assessing the condition of roadways using remote sensing and precise geographic information systems could help cities set priorities and distribute transportation resources more efficiently and equitably.

If downsizing an infrastructure network is not physically feasible or politically possible, a city could look at ways in which changing practices in one infrastructure management sector may result in cost savings or efficiency improvements in other sectors. For example, decommissioning roads in flood-prone areas could reduce stormwater management costs, building a case for these kinds of interventions.10Hoornbeek and Schwarz, “Sustainable Infrastructure in Shrinking Cities: Options for the Future.”

Although there are no plans to decommission additional streets in Youngstown, the project effectively curbed illegal dumping along the streets that were closed by making them inaccessible to vehicles. The decommissioning effort also opened up new possibilities for reusing the former right-of-way, as demonstrated by the Predator Zone project.

Since urgent needs can lead to creative problem-solving, experiments in infrastructure management in Youngstown could have implications for other cities with surplus capacity.

Biographies

is the director of Kent State University’s Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative. Her work at the CUDC includes neighborhood and campus planning, commercial and residential design guidelines, and ecological strategies for vacant land reuse. Schwarz launched the CUDC’s Shrinking Cities Institute in 2005 in an effort to understand and address the implications of population decline and large-scale urban vacancy in Northeast Ohio. As an outgrowth of the Shrinking Cities Institute, she established Pop Up City, a temporary use initiative for vacant and underutilized sites in Cleveland. She teaches in the graduate program for the KSU College of Architecture and Environmental Design.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.

Select Bibliography

American Society of Civil Engineers. “2019 Report Card for Northeast Ohio’s Infrastructure.” Accessed April 2, 2021. https://www.infrastructurereportcard.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/FullReport-NEO_2019_web.pdf.

Anansi Street Entertainment Media Corp. “Meet Lorenzo “Killer” Brooks.” Accessed April 2, 2021. https://www.anansistreet.com/lorenzo-killer-brooks.

Beckman, Ben. “The Wholesale Decommissioning of Vacant Urban Neighborhoods: Smart Decline, Public-Purpose Takings, and the Legality of Shrinking Cities.” Cleveland State Law Review 58, no.2 (2010).

Federal Home Loan Bank Board, Division of Research and Statistics. “Summary of Economic Real Estate and Mortgage Survey and Security Area Descriptions of Youngstown Ohio.” Accessed April 2, 2021. https://library.osu.edu/documents/redlining-maps-ohio/area-descriptions/Youngstown_Area_Description.pdf.

Graziosi, Graig. “The Sharonline receives new attention from YNDC.” The Vindicator, October 15, 2017. https://vindyarchives.com/news/2017/oct/15/sharonline-receives-new-attention-yndc/?print.

Guerrieri, Vince. “On The 40th Anniversary Of Youngstown’s ‘Black Monday,’ An Oral History.” Belt Magazine, September 19, 2017. https://beltmag.com/40th-anniversary-youngstowns-black-monday-oral-history/.

Hoornbeek, John and Terry Schwarz. “Sustainable Infrastructure in Shrinking Cities: Options for the Future.” Center for Public Policy and Public Administration and Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative, Kent State University, 2009. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2016933.

Reed, Molly. “City plans to permanently close abandoned streets in Youngstown.” WKBN News, July 21, 2016. https://www.wkbn.com/news/city-plans-to-permanently-close-abandoned-streets-in-youngstown/.

Simeon, Chelsea. “Youngstown begins permanently closing abandoned streets.” WKBN News, August 26, 2016. https://www.wkbn.com/news/youngstown-begins-permanently-closing-abandoned-streets/.

Woodberry, T. Sharon. Email correspondence, July 9, 2020.