Along the Lumbee River, North Carolina

Stories from the Inside: Four Eras of North Carolina Prison History

Along the Lumbee River begins with a set of oral histories compiled by public historian Kimber Heinz that discuss the interconnected histories of North Carolina’s roadway development and carceral system. Both of these state infrastructures have origins in the legacy of slavery, as forced chain gangs were used to build roadways such as Interstate 74. This history still lingers today, not only in the highways that serve as a primary mode of connectivity, but also in the built structures that once incarcerated these chain gangs.

Heinz’s investigation weaves together firsthand accounts of life during the chain gang era with contemporary discussions of the necessity of uncovering and centering shadowed histories in justice work. The methodologies that Heinz presents for developing projects based in public cultural histories provide the foundational theory of this report and are highlighted in the other contributions. Her ideas have played a central role in the development of GrowingChange, a youth-led, North Carolina-based nonprofit social organization whose work informs and connects much of this report. To learn more about GrowingChange, read From Prison to Farm: Lifting Up a New Generation. —Morgan Augillard and Joey Swerdlin, Along the Lumbee River report editors

Download the map. Credit: Research and map by Jonathon Brearley/Group Project

GrowingChange History Project

“No one in these museums looks like me,” one GrowingChange Youth Leader noted. Together, the group’s members came to an understanding that they wanted GrowingChange to share histories from their Black, Indigenous, and people of color communities. They especially wanted to highlight stories from people who were formerly incarcerated at the Wagram Correctional Facility, which is currently being flipped into the GrowingChange Farm.

Visit the GrowingChange History Project for additional stories, regional history, and a more detailed look at its work.

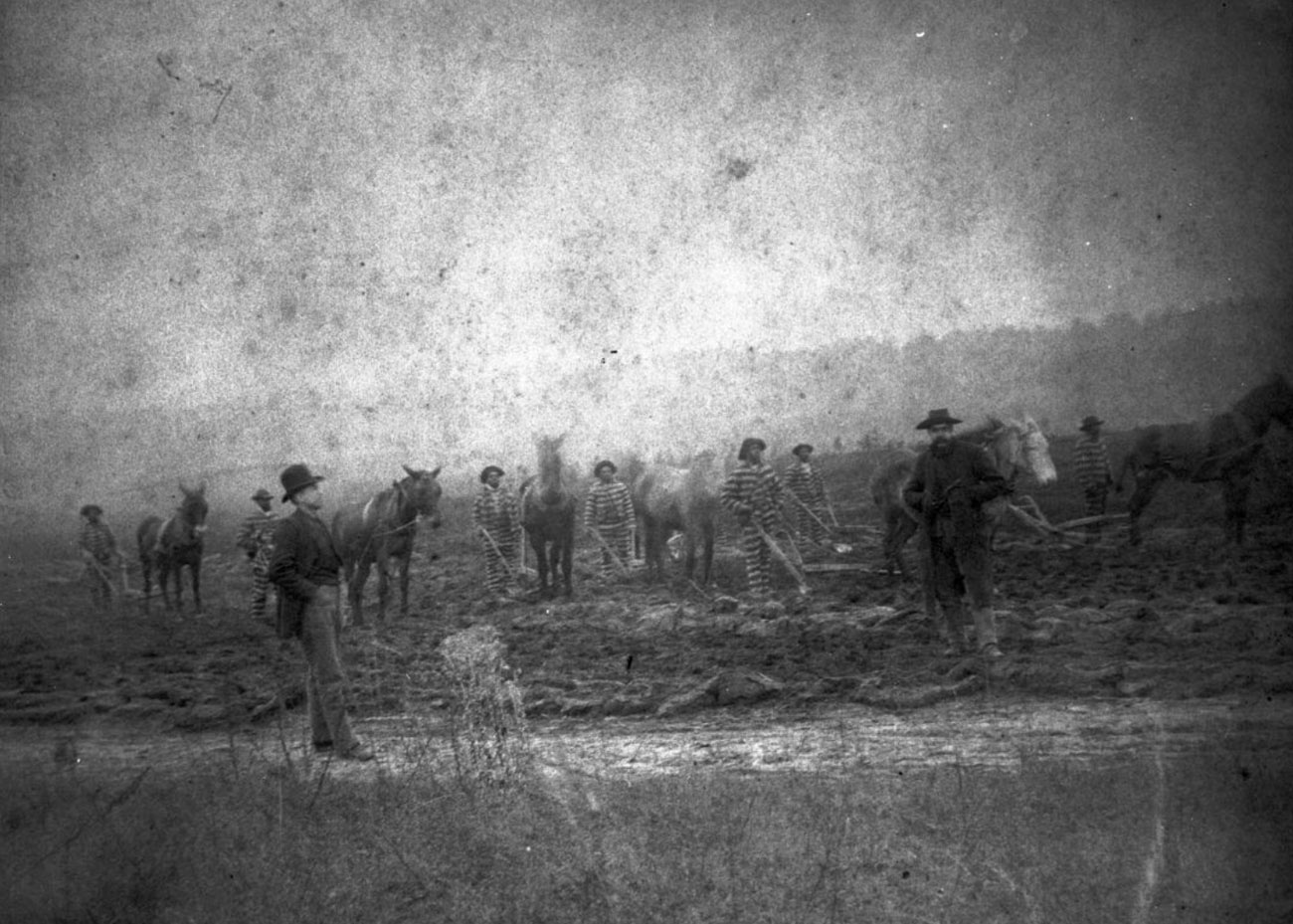

A 1930s road camp-era prison1Alex Lichtenstein, “Good Roads and Chain Gangs in the Progressive South: “The Negro Convict Is a Slave,” The Journal of Southern History 59, no. 1 (1993): 85-110.2Amanda Hughett, “Silencing the Cell Block: The Making of Modern Prison Policy in North Carolina and the Nation,” (PhD Diss., Duke University, 2017)., the Wagram Correctional Facility became the focus of the GrowingChange History Project’s ongoing research. The work draws on the writings of historians such as Alex Lichtenstein and Douglas Blackmon to deepen the collective understanding of the role of prison labor in reinventing the economy of the South after the close of the Civil War.3Alex Lichtenstein, Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South (New York: Verso, 1996).4Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by another name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Doubleday, 2008). This was a time when landowners relied on paying low wages to mostly Black farm workers through the sharecropping system, and the government forced mostly Black prisoners to build roads to transport the crops they grew across the region. GrowingChange’s original research into the history of the North Carolina road camp prison offers insight into how it was used as a means to reinstate forced labor after the emancipation of enslaved peoples.

The GrowingChange History Project believes that understanding more about the origins of a modern-day prison system can tell us a lot about the root causes of the crisis of mass incarceration today. It is grounded in the core idea that sharing silenced histories can invite community reflection and participation. This is one reason why it continues to draw in local community members as participants in the process of sharing Wagram prison history, as well as its significance and legacy.

Below are voices from GrowingChange History Project’s research on four eras of prison history in North Carolina, from after the legal end of chattel slavery through today’s modern system of mass incarceration.

“No one in these museums looks like me.” – GrowingChange Youth Leader

“You have to tell your story—otherwise someone might tell it for you—and get it wrong.” – Noran Sanford, Founder and Executive Director, GrowingChange

North Carolina’s First Prisons

The first prisons in North Carolina were built soon after the legal end of chattel slavery and the end of the Civil War.5Jesse Frederick Steiner and Roy Melton Brown, The North Carolina Chain Gang: A Study of County Convict Road Work, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina press, 1927).6North Carolina Department of Public Safety, History of North Carolina’s Corrections System, Accessed February 26, 2021. For many formerly enslaved Black people, imprisonment meant a return to chains and a new form of enslavement. The US constitution had outlawed slavery, but allowed forced labor “as punishment for a crime.” Taking advantage of this, white elites supported new laws that targeted Black people in North Carolina. In doing so, they created legal mechanisms to imprison the recently freed and put them to work. This was one strategy among many they used to maintain power.

Prisoners and guards at Hinton Plantation prison farm, Wake County, NC, ca. 1900. Credit: Courtesy State Archives of North Carolina

Charlie P. McMillan and Lonnie McPhatter

Mr. McMillan and Mr. McPhatter, who grew up near Wagram in the 1940s, remember what life was like for Black sharecropping families and workers during Jim Crow. They recall the cycle of debt to white elites.

McMillan: Wagram was a prejudiced town at that time, and a Black man really had a hard time in Wagram … whether he was in prison or not, he had a hard time. And there were some good people that, although they knew they were in charge, but they treat you like you were human. There was some that treated you like, you know, if you got a pet and he belong to you, so you do him like you want to do him. To me, it was like we were practically almost still in slavery.

McPhatter: We lived on Steel’s place, John Steel. And we lived there until my daddy saved up enough money to buy some land up in the Sandhills there. We used to bring cotton from up there down the road to the gin down there. The gin was called W.G. Buie. He owned the gin, and he owned the store across from the gin. And you would come down there, and you would bring the cotton … they had a little office over there at W.G. Buie’s store where you would scale your weights in there, and they added them up or whatever … And my daddy used to come down there—you would have to borrow money at the first of the year to get your farm, but we’d wind up always finding out at the end, we were still in debt. We would, my daddy, would sell the seeds from the cotton. He would take the seeds, what he got out of the seeds, and we would buy groceries with it. The rest would go towards the debt. But we never got out of debt. And that’s how they consumed a lot of the land that the people already had. People would buy some land, and they would get to the point of debt, and then they would consume it.

McMillan: W.G. Buie owned all of Wagram just about. Buie owned the gin. He owned … the mule, the land. Everything was his. And you sharecropping, you paying for your part, and you never get out of debt. As time passed and things got a little better, they would come and say—like, my daddy’s name was C.P.—and they would say, “C.P., you just got out of debt this year. You just made it out of debt. You didn’t have nothing in the hole.”

McPhatter: So you got to go back into debt.

McMillan: So you go back into debt at next year’s crop. But you did make it out of debt. Of course, you used to didn’t even get out of debt. I didn’t go off to the city. Wasn’t anything here to do but pick cotton and pull corn. Top cotton in line. You work all day for three dollars a day, and that was an up-pay then. I mean, we never was given the opportunity to do nothing but what we were doing. Had they given us the opportunity to do something, we might have done better.

The Chain Gang Era

Imprisoned people built North Carolina’s roads. People incarcerated in the state’s prisons worked on railroads, farms, and factory floors, but most dug and graded roads. It was dangerous work; conditions were bad and prisoners worked “under the gun” of law enforcement without adequate food or medical care.

In 1930, North Carolina’s highway department took over its prisons. It built dozens of new prisons, including Wagram’s—each one a road labor hub. Consider that: The State’s transportation department constructed road camp prisons and oversaw forced labor of prisoners. Within a few years, most of North Carolina’s 100 counties housed a road camp prison. Until the 1990s, North Carolina had the highest number of prisons in the country.

Sarah Blue, ca. 1940. Blue cared for Wagram prison superintendent Archibald Thames’s children and lived near the prison with her family. Courtesy Betty Blue Gholston

Betty Blue Gholston

Ms. Gholston, Scotland County Commissioner, who grew up in Wagram in the 1950s, reflects on her father, Lacy Blue, who many remember as the first Black employee of the North Carolina highway department. Her mother, Sarah Blue, cared for the Wagram prison superintendent’s children.

My connection to the Wagram prison site was my daddy, Lacy Blue, who worked there at the highway department, which was a part of the prison. The superintendent was over the prison as well as the highway department. So my daddy worked for the highway department and therefore he worked somewhat with the prisoners, also. And he was called Road Drag because a lot of his work was dragging the roads, and we had a lot of dirt roads at the time. And so they drug the roads to make them passable, and people would maybe use them…

Lacy Blue, North Carolina Highway Department employee, ca. 1940. Known as “Road Drag,” he oversaw prisoner road work. Courtesy Betty Blue Gholston

My grandmother must have kept me while my mother was working because you know we lived in that prison home out there by the house—out there by the Spring Hill Middle School … went to Spring Hill Middle School. There’s a white house sitting back there in the woods, and that’s where apparently we lived—that’s where I was born. And apparently my grandmother kept me while my mother worked because my mother walked from that house to cross over to the house that was on the prison ground. But she went there … she worked there every day, and she was taking care of Johnny’s daddy, and his aunt—Bobby and Betty. And in fact, how my mother ended up there was Mr. Thames came and found my daddy and said, “Lacy, if you let Sarah work helping my wife out in raising my two kids, Bobby and Betty, I will give Lacy a job working on the highway department.”

Well, I mean, that was something to think about—no Black man had ever worked for the highway department, or for the State. So therefore my daddy said yes. So therefore my mama got the job, and at some point I guess they moved into that white house. My mother walked back and forth from that little house across the highway and to the white house where the Thames’s lived, and I understand she did most of the cleaning and taking care of the kids, and a cook from the prison would go over there and cook the meals.

But my daddy, in a way, was a role model for the Black youth and Black people, period. Because they’d say, “There’d go Mr. Lacy Blue, Road Drag.” But he was a role model for people because they didn’t see Black men working for the state. Now the only Black men that would work for the state would have been Black school teachers. And Black school teachers were not mostly men. The principal was a man, and the only other person that was sort of independent was the preacher, the minister. But other than that, people were sharecropping, they were working on the farm, and that’s just the way things were.

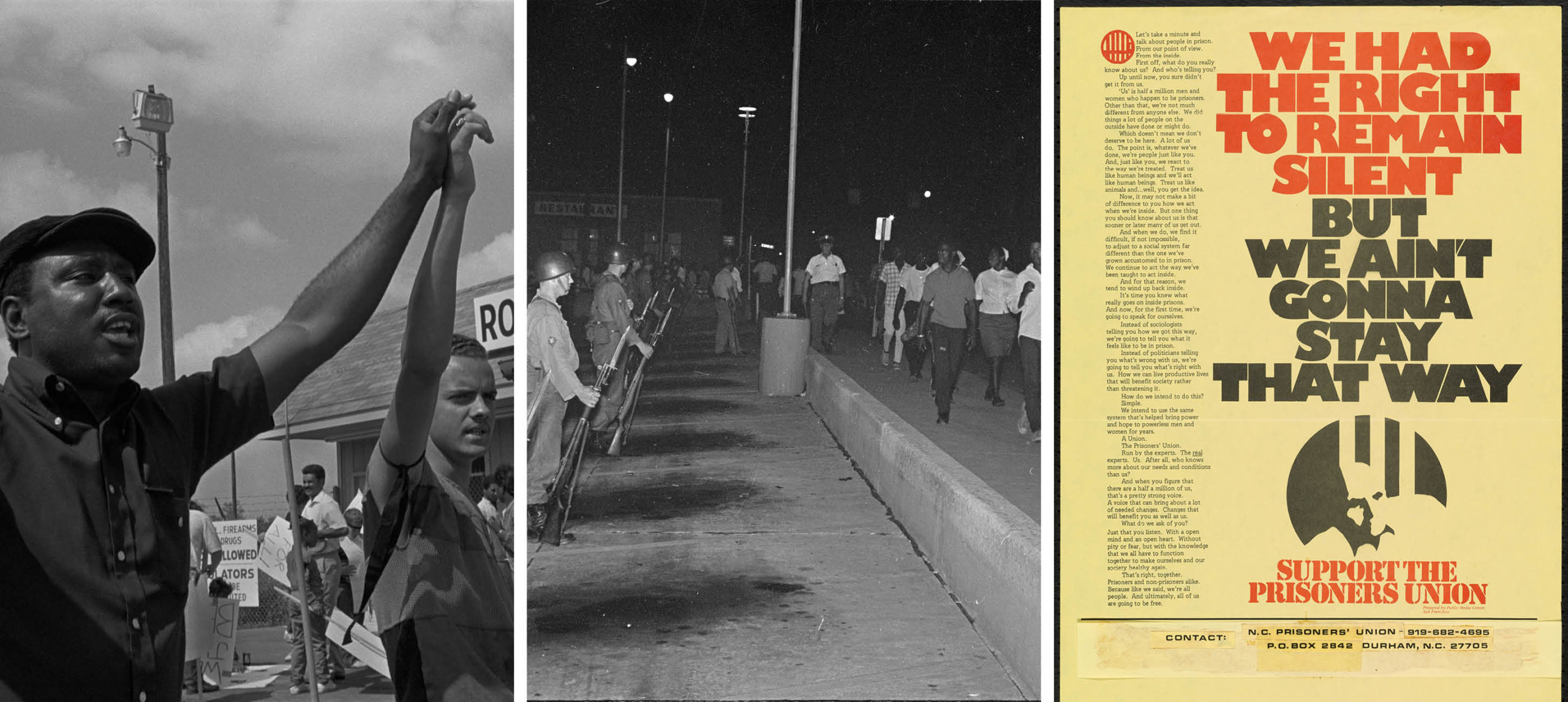

The Rise of Mass Incarceration

By the late 1960s, while the Civil Rights Movement had led to numerous achievements, society was still far from reaching true equality. Mass uprisings in many US cities including Newark, New Jersey and Detroit, Michigan with echoes in smaller cities like Durham, North Carolina erupted in response to lack of money and opportunity. Instead of ending racism and poverty, the US sent thousands more people to prison. The war on crime initiated under President Nixon and amplified by the Reagan administration dropped like a bomb on families and neighborhoods, and it hit Black communities the hardest. Through these federal policies and government initiatives, the number of prisoners working for North Carolina continued to rise.

Billy Austin

Billy Austin, who was incarcerated at the Scotland Correctional Facility in the 1970s and early ’80s, remembers daily life for people locked up at Wagram prison and the work some prisoners had to do nearly every day on the road squad.

Back then it was kind of tough. I didn’t graduate and my father wasn’t around much. It was my mom. She did all the work as far as taking care of four children. And I quit school in the ninth grade. I got my GED right there where you at now, in Wagram. But it was kind of tough, especially when you ain’t in school. But I did work.

After that, that’s when life took a terrible turn for me. I started getting in trouble—back-to-back in jail, back-to-back in prison—but I had a tough time. You know, because basically I was living on the street young, just like a lot of these young kids around here doing these days here. I was down about probably three or four different times, and I think the last time was at Wagram …

Road squad first thing in the morning. I’m out on the road squad ‘til about 2:30, 3:00 … The population—Black overpopulated then. I don’t know about now … It wasn’t no joyful ride, no matter how much good advice you get about what you going to do when you get out or how you gonna survive through this here stuff. It still wasn’t no good days. In other words, you gotta be a man—a strong person anyway—to survive.

Fifteen to thirty days in the hole for disobeying a direct order. I done that twice. And you might get two hours, you might get an hour out, maybe twice every two weeks.

The hardest part for me was the road squad. You know, because you got to go out there, and you may be picking up paper beside the road that day or whatever. You may be cutting right-of-ways. Like when I got both of my eyes swollen from wasps, that was about the hardest time for me right there. You know, was going out there and working on that road squad and coming in every day, and that’s something you got to do. If you not down there when they call your name at that fence to go out to the road squad that day, you get a major write-up and get sent straight to the hole. We even had, up here in Laurel Hill, they had a ditch out there that they would dig, and then it’s like one man here, one man there, one man all the way at the bottom—and the ditch was deep enough to drive the bus down into it, and you couldn’t even see the top of it. That’s how deep the ditch was.

It was overcrowded then. I mean really overcrowded. Most in there were Scotland County, and the most in there were Black, back then.

Creating Change in North Carolina

At the beginning of the new millennium, the overcrowding of prisons in North Carolina reached a boiling point. Instead of reducing incarceration, the State built bigger prisons. While North Carolina closed many of the small road camp prisons like the one in Wagram, the total prison population continued to grow, aided by the increased capacity of the new facilities.

This contemporary crisis of mass incarceration is the result of a highly designed process rooted in slavery. It continues to harm our communities; we must find new alternatives to prisons. GrowingChange is offering one model to do this through repurposing a prison to beneficially serve community needs.

Left: Black and Native solidarity protest against racism and police violence, Lumberton, NC, just outside Scotland County, ca. 1988. Credit: Rob Amberg, robamberg.com Middle: Durham, North Carolina, residents march against local government decisions keeping Black people in poverty, 1967. Image 1-03-26-315, Durham Herald Co. Newspaper Photograph Collection #P0105, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Right: The North Carolina Prisoners’ Union organized for better conditions, ca. 1975. Credit: Special Collections & University Archives, J. Murrey Atkins Library, University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Terrence Smith

Terrence Smith, who has been a Youth Leader with GrowingChange since its founding in 2015, remembers the early days of GrowingChange and when he first saw the old Wagram prison site. He reflects on the injustice of mass incarceration and the power of the GrowingChange model.

I always lived in Scotland County. The home that I live in now, my grandparents built. Well, actually the whole family built it, so, like, the family house, and I’m responsible for it now. And my grandfather always gardened and farmed and did agricultural stuff in our area. He always tended to a lot of different fields outside of his own. That’s how he put food on the table. And he still had his own garden and stuff going on. He grew vegetables, fruits, raised hogs, chickens, eggs, things like that.

I was 11, 12. I got in trouble in school, and that’s how I got involved in the court system. One of the conditions of my juvenile probation was that I had to be in school and not get suspended. And I didn’t comply, so I got a violation, and they sent me to wilderness camp. And while I was in the wilderness camp, Mr. Sanford, he came to check on me from time to time … Before he took me home, he was like, “Hey man, do you mind if we swing by the garden, I want you to see something real quick.” And so I figured he knew about my family and stuff that I knew, and I figured maybe he needed some pointers or some help with something real quick. So, we stopped by the garden; it was an empty plot. He says, “I’m thinking about putting a group together, young men your age, and we’re going to grow food and give it away to needy families.” And I was like, “Well, you know, I won’t be doing nothing else better in the summertime, so I might as well come out and see what you’re talking about.” So that’s when GrowingChange began.

We started out as a community garden down behind a church in Laurinburg, the Presbyterian Church. And then we went on a field trip out to the prison site. We had been doing a whole lot of different other stuff, like gardening techniques, growing techniques, and all this urban agriculture stuff. So we went out there and met Eddie Poole, who was a [North Carolina department of public safety] steward over at that site at the time, and he told us about the bigger plan. We kind of thought he was trippin’ a little bit, and then as we began to work through the different avenues and figure out the different avenues and things that we had to do to make it possible, then it became more realistic. Or it seemed to be more realistic.

A lot of different projects. The community garden, where we started at, we built the greenhouse, and that was a very elaborate project, because we had to dig into the ground and run water out there. We had to do plumbing, construction work, all kinds of work.

I’m a firm believer that everybody can change, but they just have to see themselves being differently. That’s kind of like kids in the neighborhood. You have them in this neighborhood; there’s all this bad stuff going on around them. They’re absorbing it. They’re soaking it all up … The work that we’re doing with GrowingChange, we’re trying to figure that out, and trying to frame up the reformation of how we deal with troubled youth and how we see troubled youth and things like that. I’m an advocate for young troubled people, because I was once one.

The prison system, I would say it’s a joke, but I mean, 20 years in the box is not no joke. For the majority of people who go to prison and get out, they do not do good, because it’s not designed for you to do good. You know, most people that are incarcerated look like me, or they are people of color. It’s not designed for us. It’s designed to keep the people on the top at the top and the people at the bottom on the bottom … When you get in the system, it’s hard to get out.

Biographies

is a public historian and exhibit developer based in Mebane, North Carolina. Founder of Scaffold Exhibits & Consulting, she is an experienced curator, oral historian, and researcher whose roots are in community organizing.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.