Taking humor seriously

An interview with Mustafa Faruki, winner of the 2017 League Prize.

The League Prize, an annual competition that asks young designers to respond to a given theme, has marked an important milestone in many architects’ careers since it was established in 1981. Winners showcase their work through a lecture series and exhibition.

Mustafa Faruki was one of the 2017 prize recipients. He discussed his work with the Architectural League’s Catarina Flaksman and Matt Ragazzo.

Flaksman: This year’s theme for the League Prize competition is “Support.” What does it mean to you and to your work?

Faruki: There are two meanings for support in the context of architecture. One of them would be the things that architects design and deliver—such as housing, which is supportive because it shelters people. Or a bridge that gets people from one side of the East River to the other. Or train stations that support travel.

But I also think of support as what architects do day to day. We’re constantly coming up with ideas—sometimes pie-in-the-sky ideas—and we have to use words and images to support these ideas, to convince people that they can be real.

Ragazzo: Can you talk about your installation for the League Prize exhibition?

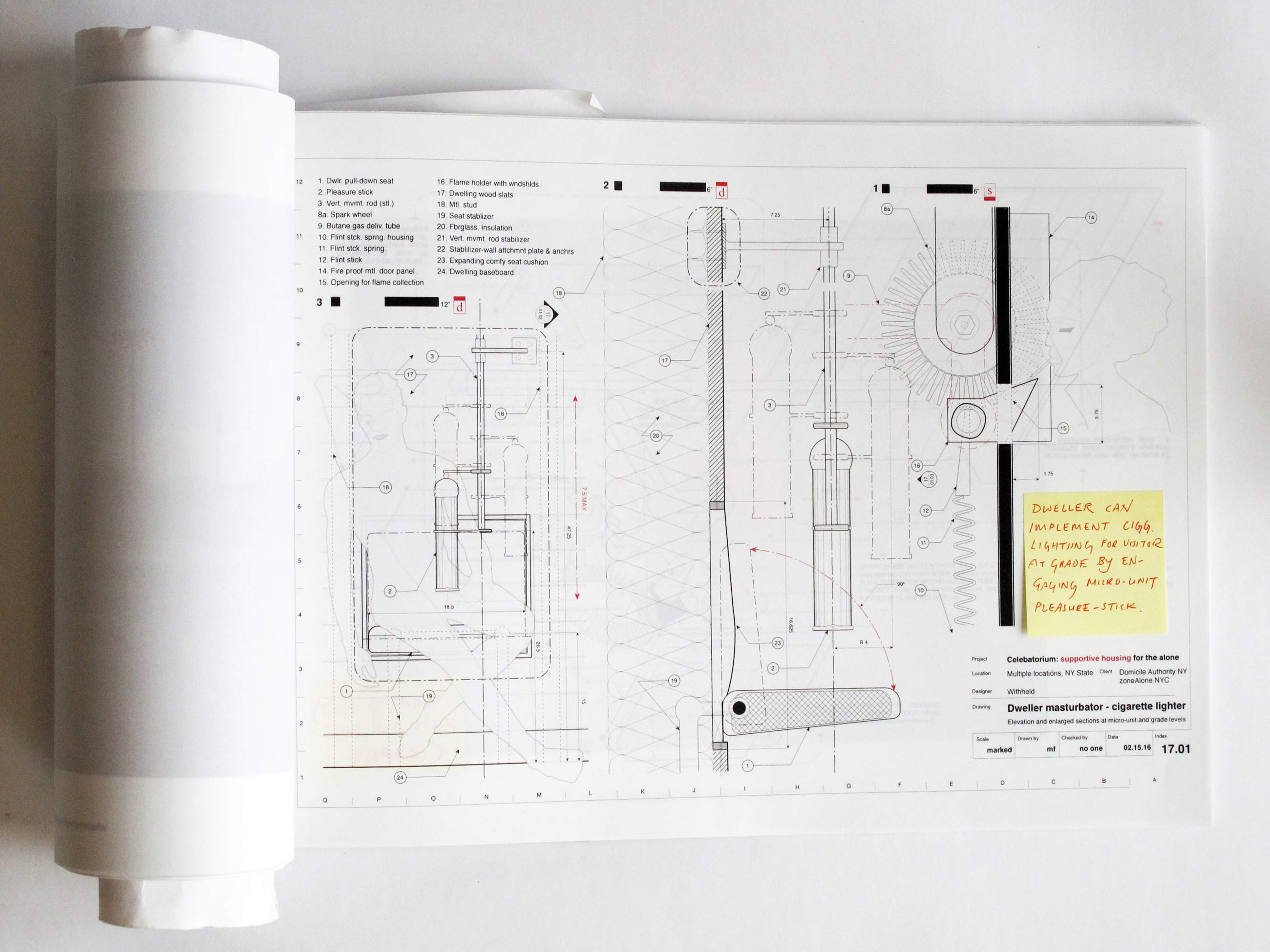

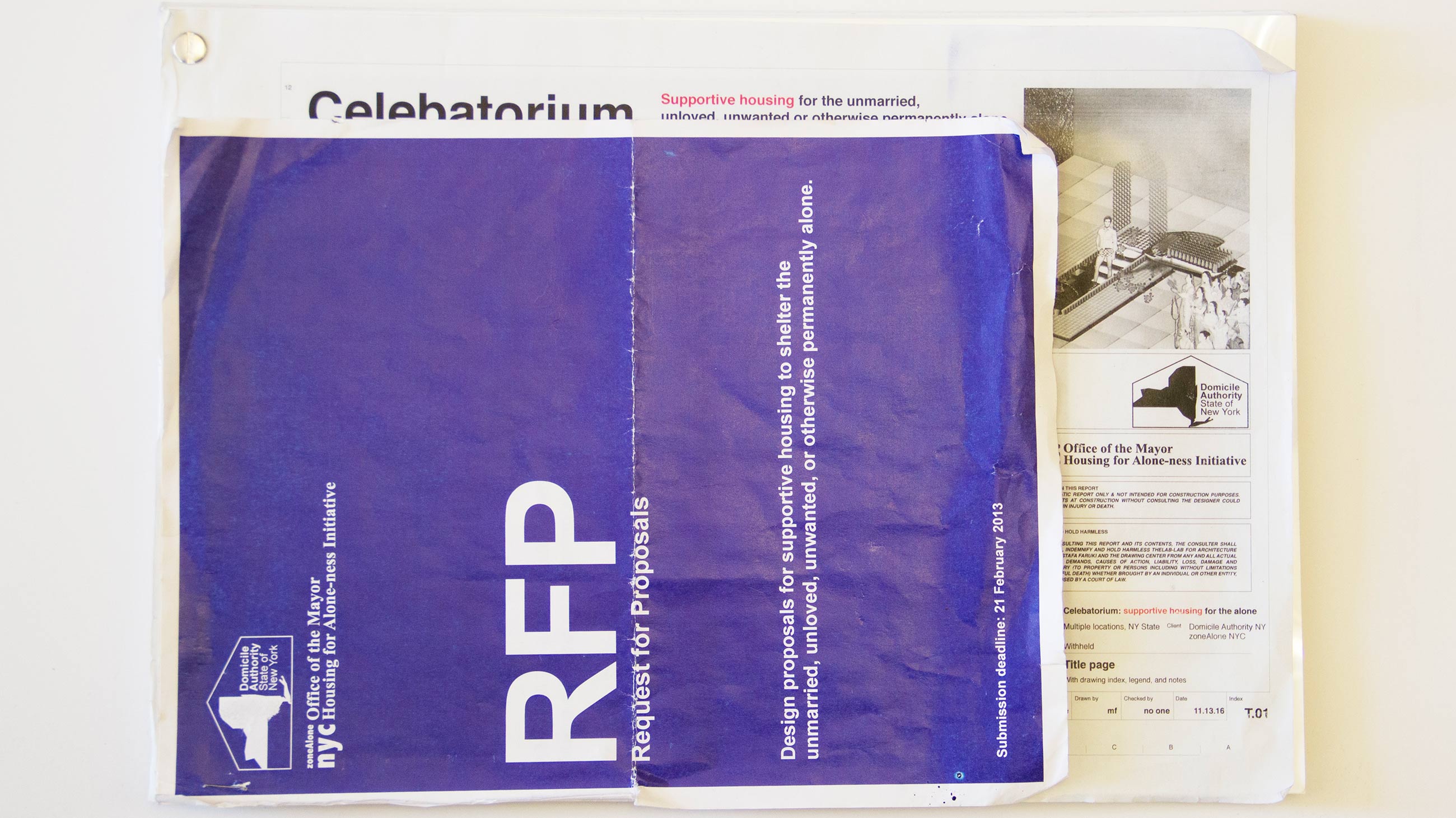

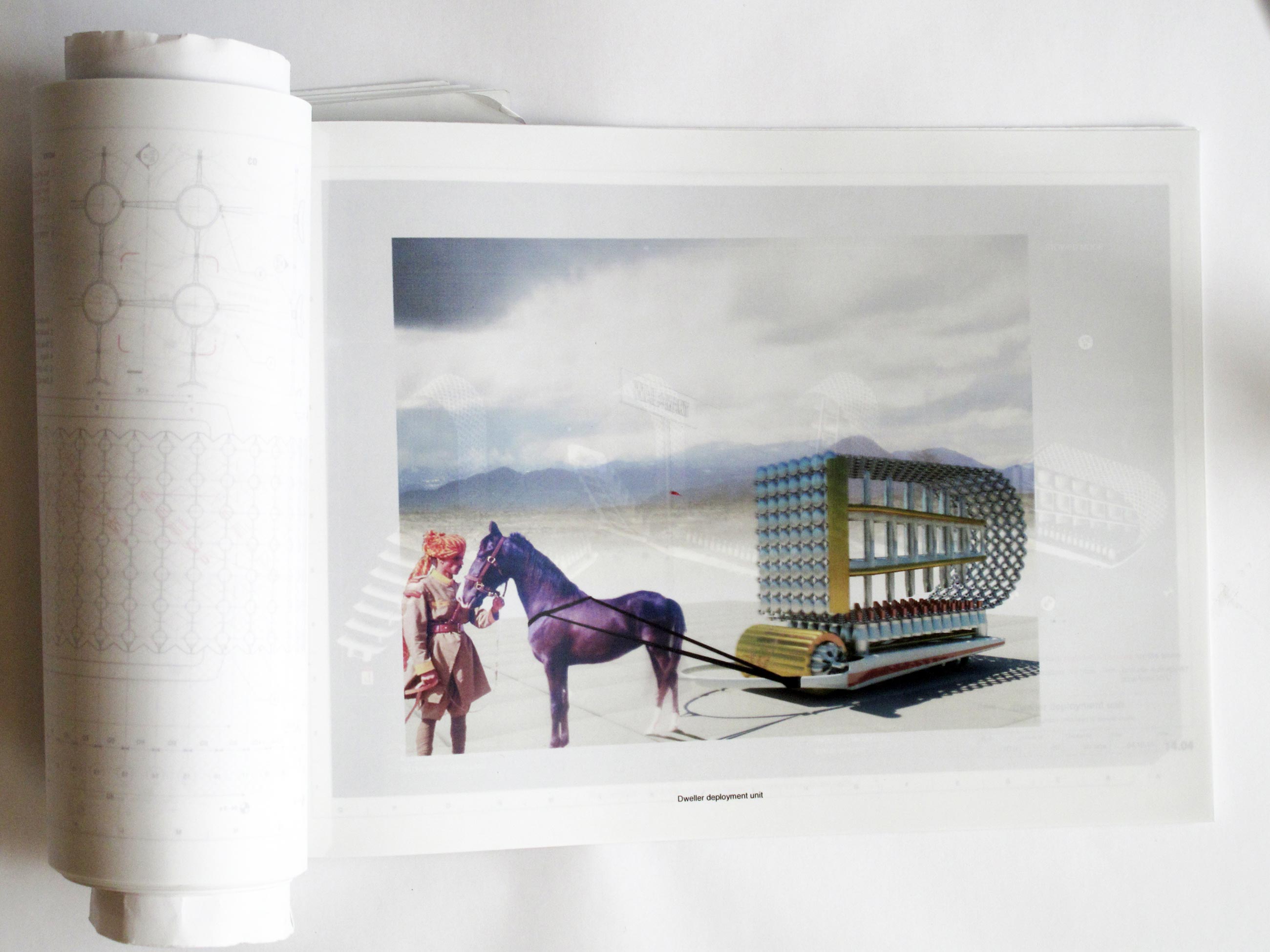

Faruki: The installation is a project called Celebatorium: Supportive Housing for the Unmarried, Unloved, Unwanted, or Otherwise Permanently Alone. It’s a micro-housing prototype for the involuntarily solitary, which also doubles as a final resting place.

Apparently dormitories of Jesuit priests in Africa and Latin America were called celebatoriums. It is ironic, because obviously they were supposed to be celibate, but I think there was a lot of sex going on in those dormitories. That’s where the title comes from.

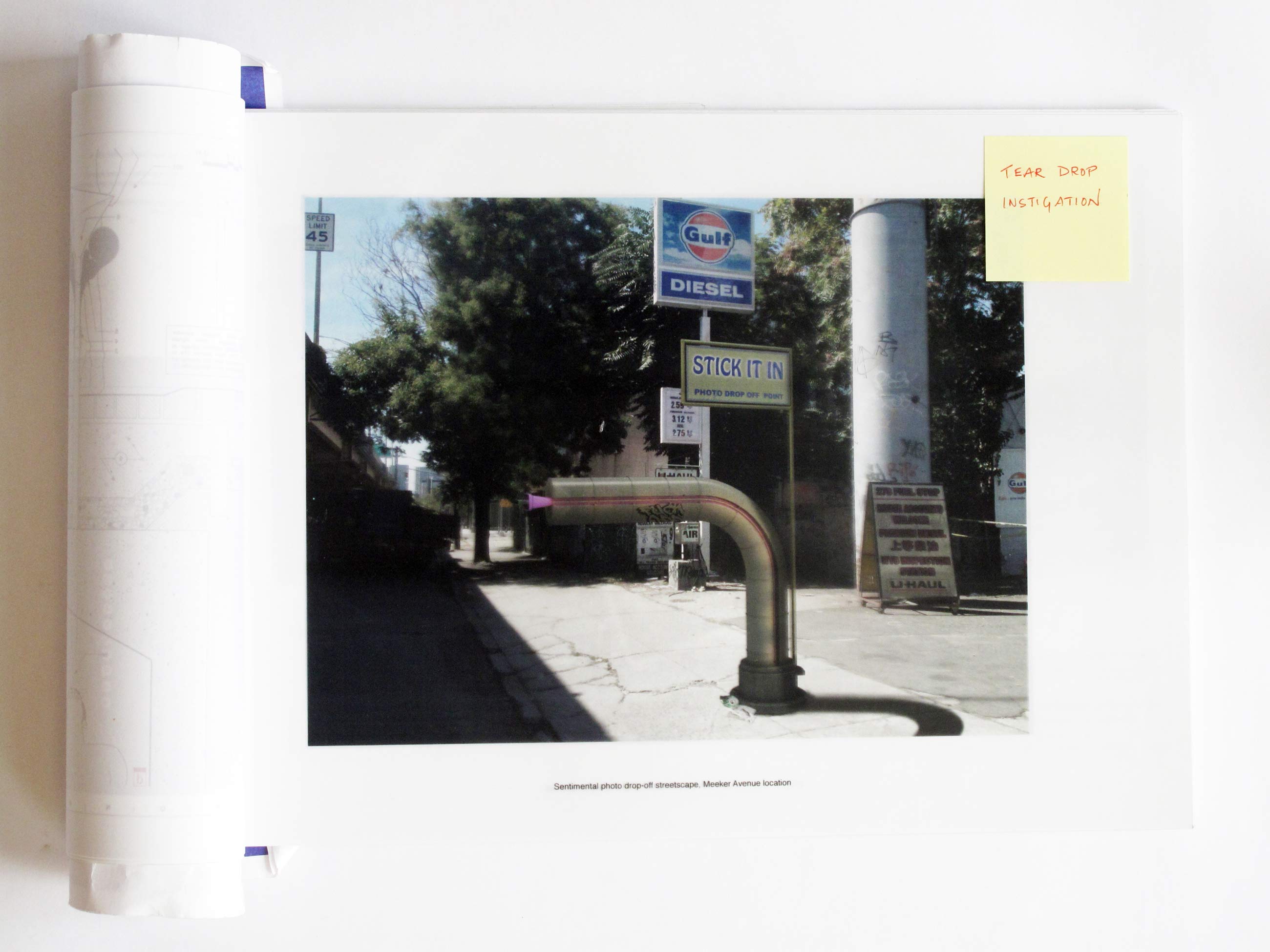

The project is responding to an RFP [also written by Faruki] that’s looking for ways to remove the permanently alone from view—but not completely. In fact, the RFP solicits “schemes that function as a vitrine”… where unrequited love, loneliness, and woe might be put on display, or even engaged with. So the project supports not just the housing needs of the alone, but also the rubbernecking needs of everyone else.

Celebatorium allows the rubbernecking, but without the traffic jam. The alone are housed in subterranean units, but their grief can still be observed. And the byproducts of their grief are extracted, harvested, and sold or used for different things.

Flaksman: What role does drawing play in your practice?

Faruki: Drawing is the work of architecture. It’s the primary rhetorical device that moves an idea forward, and it’s how we convince first ourselves and then everyone around us that our ideas are possible and true.

Ragazzo: Many of your projects can be seen as studies or fantastical architectural propositions. What is the role of these projects in your work as a whole? Do you see applications for them beyond the conceptual realm?

Faruki: I wouldn’t describe the work as studies or fantastical, but as propositions. That’s exactly what the projects are.

Look, this building that we’re sitting in, when somebody first drew it, it was a fantasy. It was just conceptual. Incidentally, conceptual design is a typical phase in most design projects. It’s a milestone, and has an associated deliverable that’s very real.

So I don’t characterize my work as conceptual architecture or fantastical architecture or anything like that. It’s architecture, full stop.

Ragazzo: So does drawing become an end unto itself? Representing something on paper versus passing the papers along to someone who then constructs the design?

Faruki: A drawing is an architectural deliverable. If the project does go into construction, then I’m happy to administer that—actually, I’d be obligated to—and that would be a separate deliverable.

I want to be clear about this: architects get paid for drawings. Drawings constitute our labor, and its fruit. And that’s absolutely how it should be. It’s incumbent on us to show our ideas with clarity and precision. Anyone can blather on about their big designs. But to pin these ideas down to paper, to demonstrate their possibility: that is the substance of our work. Whether we stand or fall as architects, financially or otherwise, depends on the efficacy of our drawings.

Flaksman: What is the importance of humor to your practice? It seems to be one of your tools to challenge architecture’s professional constraints and idealism.

Faruki: We inhabit architecture. We live inside of it. It’s stained by our sweat and the air we exhale and our piss and shit. There are fragments of all of this stuff in buildings. It also has to, then, be stained by all kinds of other things that are coming off of us, like emotion, humor, irony, lust.

In my first year of architecture school I was doing work similar to this, and I still remember one of the things my professor, Mark Wasiuta, said. I was showing him my work and he was starting to get frustrated, and he said: “You can be as funny as you want, but you have to take your humor seriously.”

I think an architectural project is kind of like a book. Part of it might be sad, and then five pages later you might be cracking up and falling out of your seat. And that’s what makes it really good. It has to include the gamut of human emotion that allows us to relate to it.

So yes: humor is definitely there, alongside grief and doubt and regret. And I suppose that, to your question, this sense of human-ness and its dynamic, imperfect, and gritty realness acts as a kind of counterbalance to the hyper-rational, sometimes overly quantifiable nature of professional practice.

Flaksman: Several of your projects deal with the theme of loneliness. Do you see loneliness as a consequence of urban life, and does the city affect your practice somehow?

Faruki: Loneliness—or actually, alone-ness—is a recurring theme mainly because it’s so ubiquitous. We’ve all felt it at one point or another. And yet it manifests itself in so many different, sometimes completely oppositional ways.

I’ll tell you the story behind one of my projects, Desert of Alone-ness. I was doing an artists’ residency in a tiny village on the west coast of Norway called Dale. The other artists were from fairly big, cosmopolitan cities—Copenhagen, Malmo, Warsaw—whereas I’m from a small town in the Adirondacks, in upstate New York. And our reactions to Dale were so different.

This sense of human-ness and its dynamic, imperfect, and gritty realness acts as a kind of counterbalance to the hyper-rational, sometimes overly quantifiable nature of professional practice.

For example, I didn’t have access to a car, so I had to walk everywhere. The others were like, “How do you walk alone in the forest like that? And at night? It’s so scary!” I explained that it was something I was used to, and that I thought nighttime walks in the city had the potential to be much scarier. Of course, they found this ridiculous!

I was really intrigued by this idea: that alone-ness could be interpreted as liberating or terrifying or just nothing special at all.

Ragazzo: Who or what are your main influences?

Faruki: In terms of designers or architects, a lot of my influences are my teachers. I love Michael Webb, who was my professor as an undergraduate. The holy trinity of intelligence, humor, and beauty that characterizes his projects continues to be an inspiration for me. And to be honest, I didn’t even appreciate his work at the time—a common college student situation, where you take things for granted, and then you realize years later that it was a wasted opportunity.

Another inspiration is Douglas Darden. He also created these intricate, very detailed architecture projects, all positioned as allegories. One of them is a house for somebody who is dying of cancer. Another one is a library dedicated to Herman Melville, built on the site of Melville’s former apartment in Greenwich Village. His projects are always asking questions—sometimes defiantly. And they are all beautifully drawn by hand, with a pencil; but so convincing, so real. His architecture takes you on this trip, and you can’t help but believe it. I aspire to that.

I also really admire James Wines, in particular the way that he articulates his practice and where it sits in relation to architectural discourse.

Poetry is another inspiration—or actually, a provocation. My mother is a poet in two languages; my grandfather is a poet in three. Most of the drawings in Celebatorium incorporate some idea or cliché that I’ve loosely adapted from a poem.

Along the same lines, I love hip hop and rap. Kanye West, Talib Kweli, Lauryn Hill, India Arie: people who play with the power of words.

I’m also inspired by whatever I happen to be reading. I’m reading Philip Roth right now, Portnoy’s Complaint. Almost the entire book is about masturbation. And religion. And family. One minute it’s so vulgar and funny and then, a few pages later, very sad and heavy. I’m influenced by that kind of narrative, how dynamic it is, and all the loops it throws you through.

Flaksman: How do you see your practice developing in the next few years? What would you like to happen?

Faruki: Well, of course I have to find some way to support myself, and I imagine that this practice becomes something that I’m able to support myself with.

Right now it’s almost like the practice is a small child. I’m holding its hand as it’s walking down the street. I have to leave it alone for many, many hours, like a latchkey child, while I go to other people to try to get their support in different ways. But I’m hoping that the practice will be able to support me one day. If you have a child, you know that one day you’re going to get really old and that child is going to be changing your diapers.

So that’s what I want this practice to do for me in a few years: change my diapers.