Dumpster divers of the digital age

An interview with Kevin Hirth, winner of the 2017 League Prize.

The League Prize, an annual competition that asks young designers to respond to a given theme, has marked an important milestone in many architects’ careers since it was established in 1981. Winners showcase their work through a lecture series and exhibition.

Denver-based Kevin Hirth was one of the 2017 prize recipients. He discussed his work with the Architectural League’s Akiva Blander and Catarina Flaksman.

Flaksman: This year’s theme for the League Prize competition is “Support.” What does this mean to you and your work?

Hirth: I really loved the part of the competition prompt that asks what props us up and how we remain upright. It’s a really relevant question for me, especially being out in Colorado. How do you engage with the discipline and the discourse of architecture when you’re somewhat removed?

For me, support is all about building a personal history. It’s like constructing a cast of characters around yourself that becomes your scene. Whether alive or not, they’re the people who I see as my family tree, or the people that help me be who I am today.

Looking back at history is really key when you’re formulating your own support. We’re surrounded by the ghosts of all of the different things our work draws from.

Pages from Hirth’s League Prize competition entry showing Hirth's House on a Fence Line and "Monument to Direct Democracy in Colorado" with precedents.

And that’s particularly relevant right now. When you look back at the postwar period, you had these heroic figures whose shadow you could perch under—Le Corbusier, [Walter] Gropius, and Mies [van der Rohe]. There was a definite scene that you could associate yourself with.

Today is different. It’s much more disparate, dispersed. There isn’t the desire, or maybe the ability, to associate yourself with one scene and be a part of that support network.

So for me, support is about creating that sense of history and association with other things that help strengthen the work. And that isn’t just architecture—it’s art, it’s history, writing, music.

Flaksman: Can you talk about your installation for the exhibition?

Hirth: I wanted to go big. I decided to make a whole project out of it and really take it as a moment to further consider that prompt of support, but also try to figure out what the context of my work really is.

Knowing that I had the restriction of having to fly to New York and wasn’t able to ship things in big packages, I tried to find a very efficient way of working.

The collage was an important step in the firm’s growth as a way of making a leap from a digital world, where a lot of my work is constructed in images. It allowed me to transpose this analog method, which has always been really important to me.

The work within the collage really sits surrounded by itself; all the projects are together in one space that is very flat and self-referential. To me, it was about trying to construct that context from the work, to allow the work to become a part of the background and have the background come out of the work.

And then with the models, I wanted to imply that those projects were ripped off the page and draped over the table. It’s almost like a messy meal that’s been laid out for dinner guests to dive into.

Flaksman: You mentioned appropriation as a form of support, and that’s very clear in the portfolio you submitted for the competition. Can you talk about particular influences and how they appear in your work?

Hirth: Assembling these references or influences is just a part of my daily life. I spend a lot of time searching for things that influence me. I see it as similar to looking through old family photo albums and seeing how relatives look similar: “Oh, I look a lot like my great uncle!”

I draw a lot on conceptual art from the ’60s and ’70s. I’m taken by the intent of artists from that period to capture everything, all at one time, and package it together, pushing different mediums past representation and bringing them into the conversation of what the art is about.

Pages from Hirth’s League Prize competition entry showing two of Hirth's projects, "Monument to Direct Democracy in Colorado" and Bacon House, with precedents.

Lately, I’ve also been looking at a lot of lithography from the 19th century. That’s also one of those moments where a craft was being pushed to its outer limit. Printing presses were developing to the edge of what they could do, and artists were pushing the medium past what it was capable of doing.

That’s the underlying theme of everything I look for: pushing past the late moment in a practice. Because I think we’re there right now. People have pushed digital methods, construction methods, all these things. We’re pushing them to their limit and trying to find a way to get past thinking about the medium as the driving force, but instead about the work itself as using that as a weapon of some sort.

My portfolio is peppered with quotes; my brain is peppered with quotes, constantly. I read a lot. Lately, I’ve been reading some of [Kenneth] Michael Hays’ writing and enjoying the way he reads Aldo Rossi.

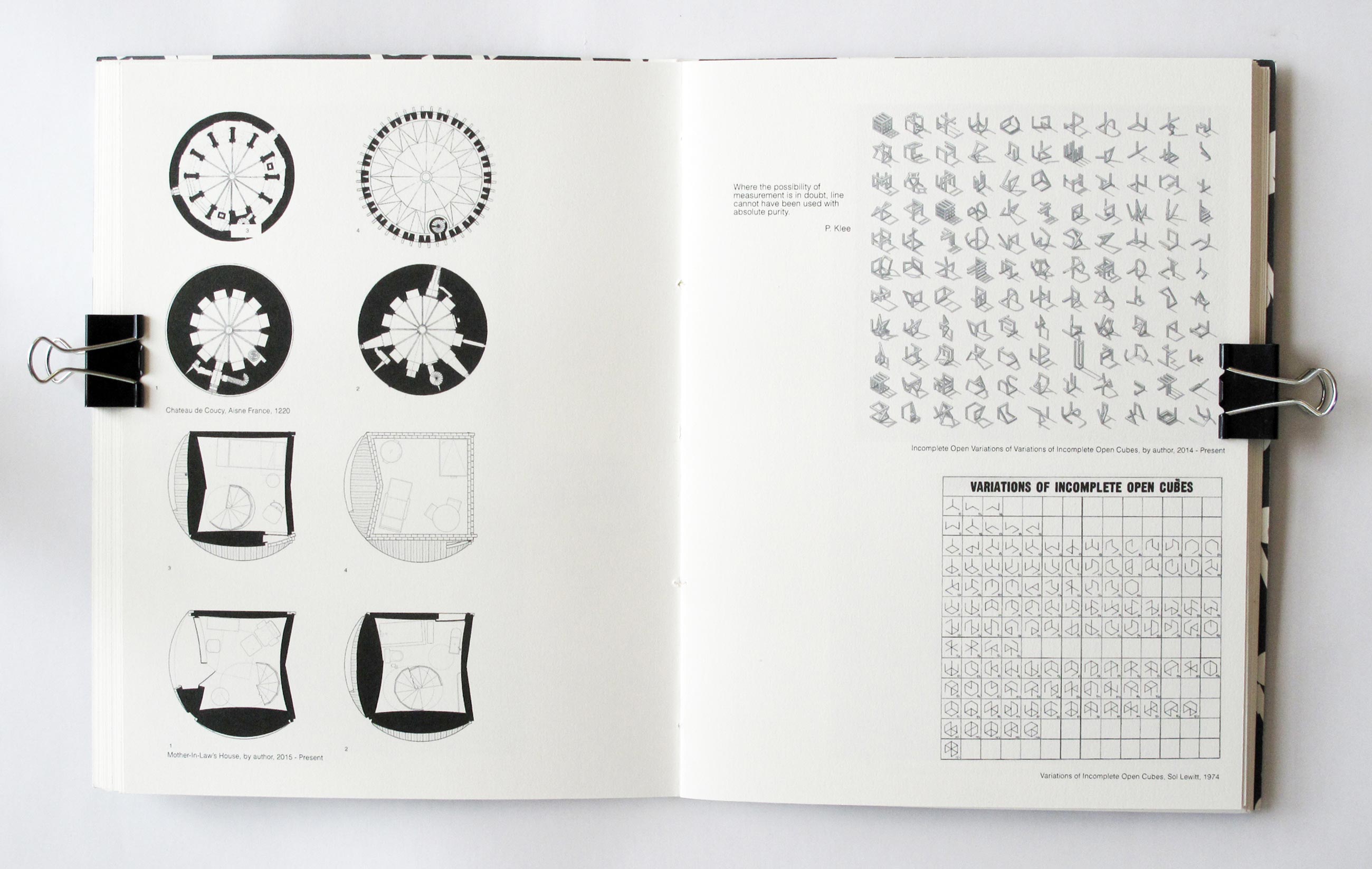

Pages from Hirth’s League Prize competition entry showing Hirth's projects "Variations of Variations" and Mother-in-Law's House alongside precedents.

Blander: In the introduction to your portfolio, you speak about this contemporary condition and say that we’re like “dumpster divers of the digital age, bargain-bin online shoppers.” And you quote Sam Jacob’s essay “Faster, but Slower,” in which he states that “everything is deflated and collapsed into an indistinguishable pool.” Do you see this as a positive or negative feature of contemporary society? And how do you view your relationship to this condition?

Hirth: I think that gets at the heart of some of the tension that I’m trying to mine in my work. I see it as both a positive and a negative. In the reality that we live in, where people are doing a lot of looking back and searching, the internet has allowed us to find things that would have been really difficult to find even five or 10 years ago. There’s this profusion of content that’s everywhere around us, whether it’s seeing a journal article that your friend posts on Facebook or going onto Tumblr and seeing forgotten Latvian op art.

My take is that it’s an opportunity to find work that actually meets you where you are, as opposed to opening up the 20th century architecture textbook and saying, “Well, that Kahn project looks kind of good, but it’s the only one here.”

This constant reinvention of communication is something we haven’t really come up with a response to, especially in architecture.

Flaksman: The projects in your portfolio are presented through these beautifully rendered images. What’s the role of representation in your practice, and can you describe how you developed this particular style?

Hirth: I spend a lot of my life in Photoshop. Similar to the example of 19th century lithography, I think Photoshop has been pushed really far in terms of capturing realism.

It’s a conversation that a lot of people are having right now as part of this discourse about a “post-digital” concept. I never really questioned a pre- or post-digital idea because I’ve never been much for super-realistic rendering in general. Honestly, I think one of my greatest joys is trying to invent a new way to do something, even if it takes 10,000 hours to do one little thing that’s different.

That goes back to the connection between art and architecture, where the medium is as much the content as the content itself. I’m constantly trying to push into new terrain through drawing. When you’re young, you have the luxury of being able to just draw things, and I’m trying to take advantage of that. I’m starting to get more into building, but for this first phase of my career, it’s been about finding that voice. That’s what made the collage so fun—though my fingers are numb from cutting around 300 square feet of paper. But I think that practice is what helps me grow.

The thing that probably distinguishes my work is just this love of doing things over and over and over again. Not worrying about whether it’s going to take two weeks or a day, and just doing it.

One of my greatest joys is trying to invent a new way to do something, even if it takes 10,000 hours to do one little thing that’s different.

Flaksman: You’ve written that your projects are “focused on the rural and urban conditions of the American West.” How do you approach this context and what are its main challenges?

Hirth: Context is something that you can never really escape. For a while architects tried, but in the end we’re talking about putting things into places.

I’m not from Colorado. There actually aren’t that many people who are, seemingly. It’s a big place full of immigrants. It’s a place that I have enjoyed and grappled with understanding because it’s so immense and remote and empty. Once you go somewhere in Colorado you’ll find yourself in the middle of nowhere and you don’t know how you got there. It’s this immense, beautiful place, so trying to find a way to work within that has been an interesting challenge.

The collage tries to show how the formal language that I’ve been developing for my work in Colorado tries to respond to it without negating that complex and grand scale of landscape.

Flaksman: Is there an intention in your projects to incorporate monumentality as a contrast to this open landscape?

Hirth: Absolutely. Monumentality is something that architecture constantly grapples with. I think Reyner Banham once said that if left in a vacuum, Americans won’t ever really build architecture, they’ll just build. But then you also find people like [Louis] Kahn saying that you can’t intentionally grow monumentality; it exists in a world and becomes itself.

So monumentality is not something that you can design. You can try to create it through scale and different things, but it’s ever-present in the Colorado landscape. When you’re driving into Denver, you think you’re seeing this tiny toy city because it’s dwarfed by the mountains behind it. How do you construct a monument in a context that constantly overwhelms the built environment in some respects?

Flaksman: How do you see your practice developing in the next years?

Hirth: That’s a difficult question. For me, winning the League Prize is an incredible benchmark. I see it as an opportunity to double down in my practice through building more. I’ve built a lot for other people in the past and completed some small projects, but I’m ready to make the step into actually making physical marks in the landscape, as opposed to these implied marks.

Blander: Could you talk about what some of these physical marks might look like and how they differ from your implied ones?

Hirth: I spend a lot of time working on housing and houses. That’s purely through opportunity, but it’s also something I’ve grown really fascinated with. The average American has a lot more flexibility in what they can live in than they think. I want to continue to challenge those issues of domesticity and domestic scale. There’s a lot more to invent there than people realize.