Forms of aid: Architectures of humanitarian space in Nairobi, Kenya

Benedict Clouette and Marlisa Wise write about urban and architectural consequences of international humanitarian operations.

August 7, 2019

The entrance to the Médecins Sans Frontières health clinic in Kibera, Nairobi. Credit: Benedict Clouette & Marlisa Wise.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Benedict Clouette and Marlisa Wise received a 2012 award.

In theorizing the operational arena of international relief organizations in the early 1990s, Rony Brauman, the former director of Médecins Sans Frontières, proposed a new term, the concept of “humanitarian space”. Humanitarian space, as articulated by Brauman, is a nonpartisan arena of operations, decision-making, access, and movement for relief organizations, where they are “free to evaluate needs, free to monitor the delivery and use of assistance, free to have dialogue with the people.” The concept of humanitarian space asserts the relative autonomy of a moral sphere that, in invoking a universal humanity and political neutrality, attempts to transcend national boundaries and local politics, and yet must nonetheless embed itself within particular spatial–political relationships. Despite its claims to universality, humanitarianism produces highly specific spatial consequences in the cities and regions that it temporarily incorporates. In responding to disasters and conflicts in the name of humanity, contemporary humanitarianism has engendered new urban forms, often through the convergence of nongovernmental actors with economic, military/security, and national interests. As architects, it is these forms, the spaces of humanitarian space, that are our concern, in that they suggest the contours of international humanitarianism as it is practiced and as it reorders cities around the world.

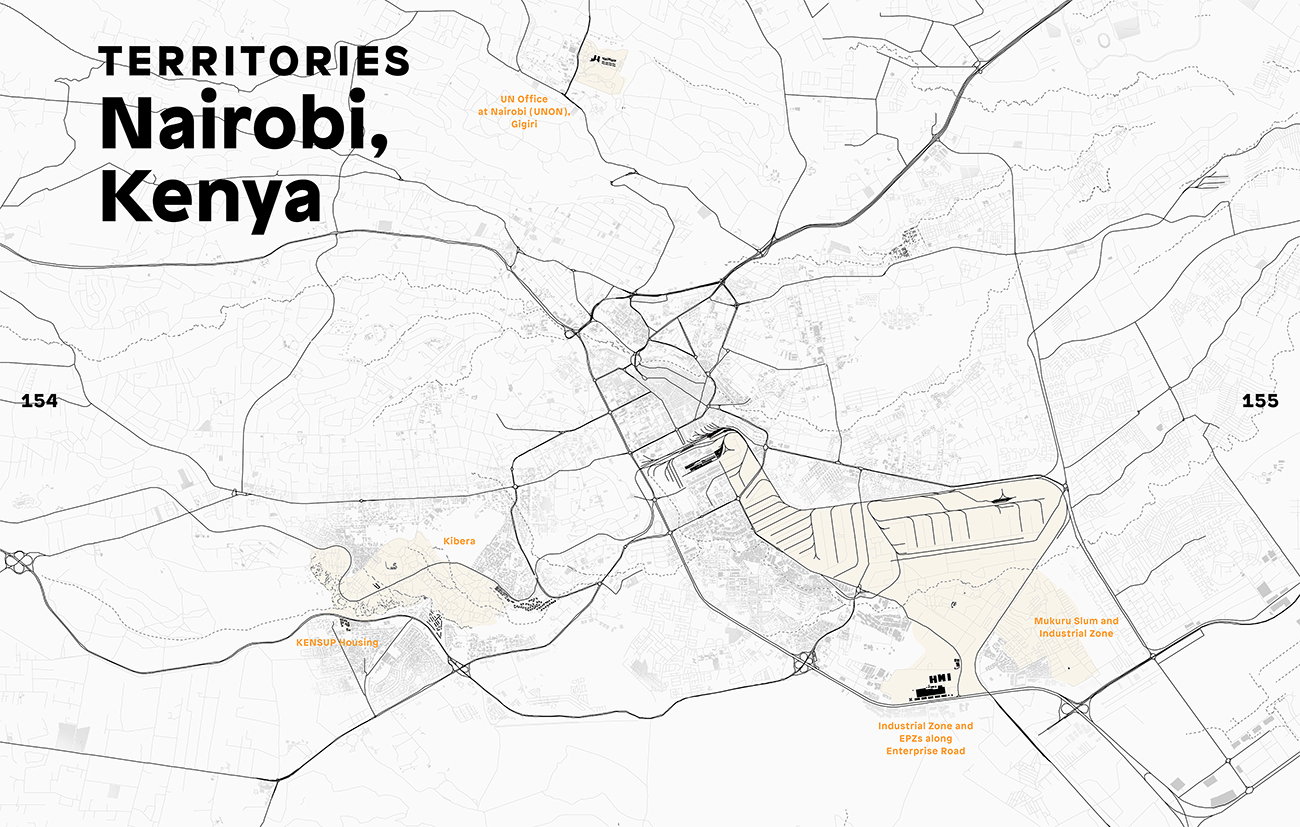

The grant from the Deborah Norden Fund supported research on the urban and architectural consequences of international humanitarian operations in the context of the city of Nairobi, Kenya, which we undertook in 2013. We documented a series of sites throughout the city that describe the complex relations between international aid and processes of urbanization. The research focused on a “slum upgrading project” in the settlement of Kibera, called KENSUP, undertaken by the government of Kenya in cooperation with UN-Habitat, and situated that project in relation to other sites across the city, including the UN’s African headquarters in the suburb of Gigiri and an industrial processing zone that houses the distribution centers of international aid organizations and relief supply manufacturers.

The research suggested an alternative to the image of Nairobi as a city of isolated extremes, where wealthy estates abut slums, divided only by the walls of private compounds. The urbanism of Nairobi’s humanitarian bureaucracy suggests instead the interdependencies between “informal” settlements, globalized markets, international institutions, and urban politics.

The city of Nairobi and the humanitarian operations it hosts comprised one of three sites of research that we developed in the book Forms of Aid: Architectures of Humanitarian Space (Birkhäuser, 2017).

Forms of Aid describes the spatial products of international aid at the scale of the building and the city, drawing attention to the responsibility that architects bear for the production of humanitarian space. The book provides a glimpse into the lesser-known spatial manifestations of aid: not just schools and clinics, but also free-trade zones, highways, checkpoints, nature preserves, cruise ships, factories, and surveillance technologies.

Architecture pressed into service of an idea of a universal humanity often obscures more complicated attachments or complicities between the altruistic mission of relief organizations and the machinations of political and economic actors. These include international NGOs, national governments acting as donors of development aid, private foundations and philanthropies, corporate social responsibility programs, and supranational organizations like the UN, WHO, and the World Bank—not humanity as such, but a very particular set of organizations, infrastructures, legal codes, and technologies. Much of what we wanted to pursue in the research for the book concerned this series of entanglements that take cover under the name of humanitarianism—and the ways in which the humanitarian project is enlisted, often knowingly, in the interests of national or international security and economic globalization.

Humanitarianism between the universal and the particular

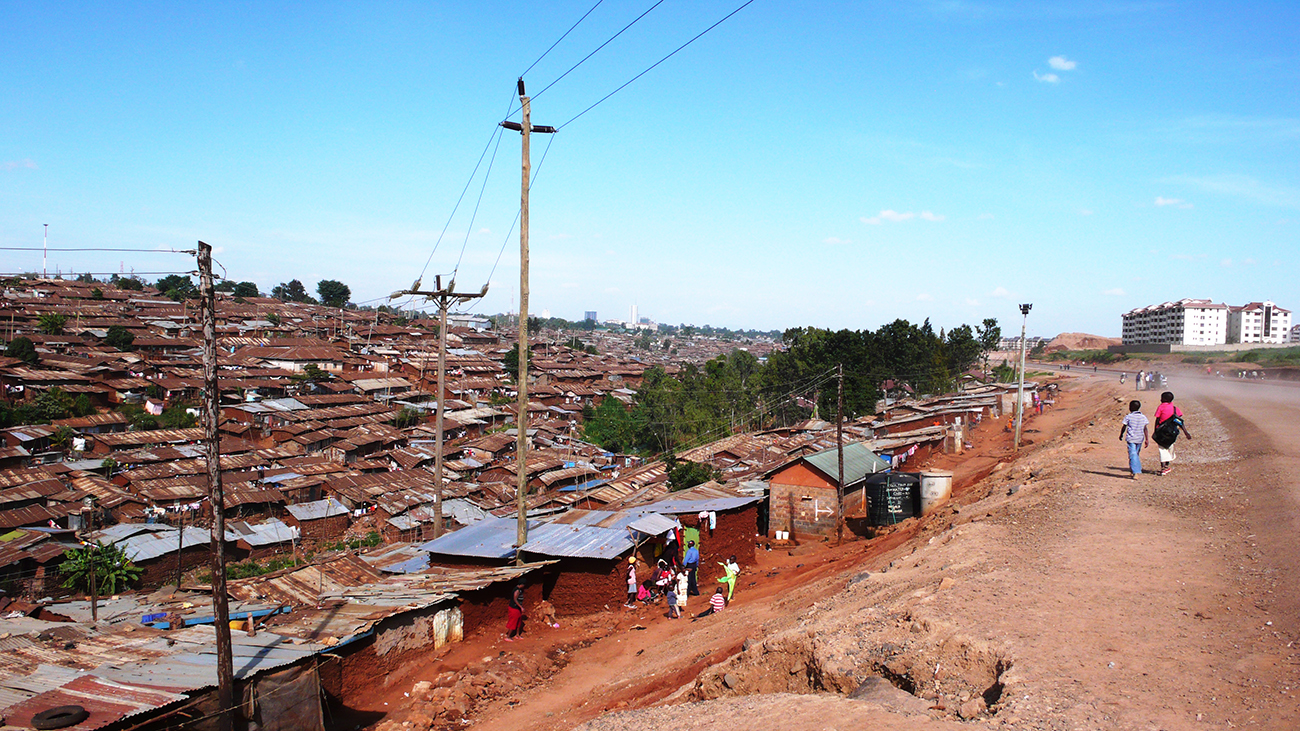

In Nairobi, we examined the urbanism that results from the imbrication of international humanitarian operations with local and national interests, considering the slum upgrading program in Kibera as a project of “humanitarian government,” to use an expression developed by anthropologist Didier Fassin. As Fassin has described, humanitarian government works not only across national borders, but on the very boundaries between state and non-state formations, between universal moral imperatives and particular political conflicts. The result is a form of international humanitarian order that is sustained through the coordinated activities of NGOs with national and local governments, supranational organizations like the UN, military operations, and multinational corporations.

The main assembly building of the UN Office at Nairobi (UNON) in the Gigiri suburb. Credit: Benedict Clouette & Marlisa Wise.

In Nairobi, we considered the forms of humanitarian government that have been organized around the construction of a large housing estate under construction in the Kibera settlement. The project, which is a joint effort of the UN and the national government of Kenya, is intended to resettle thousands of residents of the settlement, replacing several acres of self-built single-story houses that were demolished to clear the ground for the future project.

Humanitarianism and extraterritoriality

Another aspect of the research concerns the extraterritorial status of humanitarian spaces. The best-known example of the extraterritoriality of humanitarian space are the land parcels on which the UN’s four headquarters are built, which are geographically located in New York, Geneva, Vienna, and Nairobi, but legally hold extraterritorial status, governed by international law rather than the local jurisdiction.

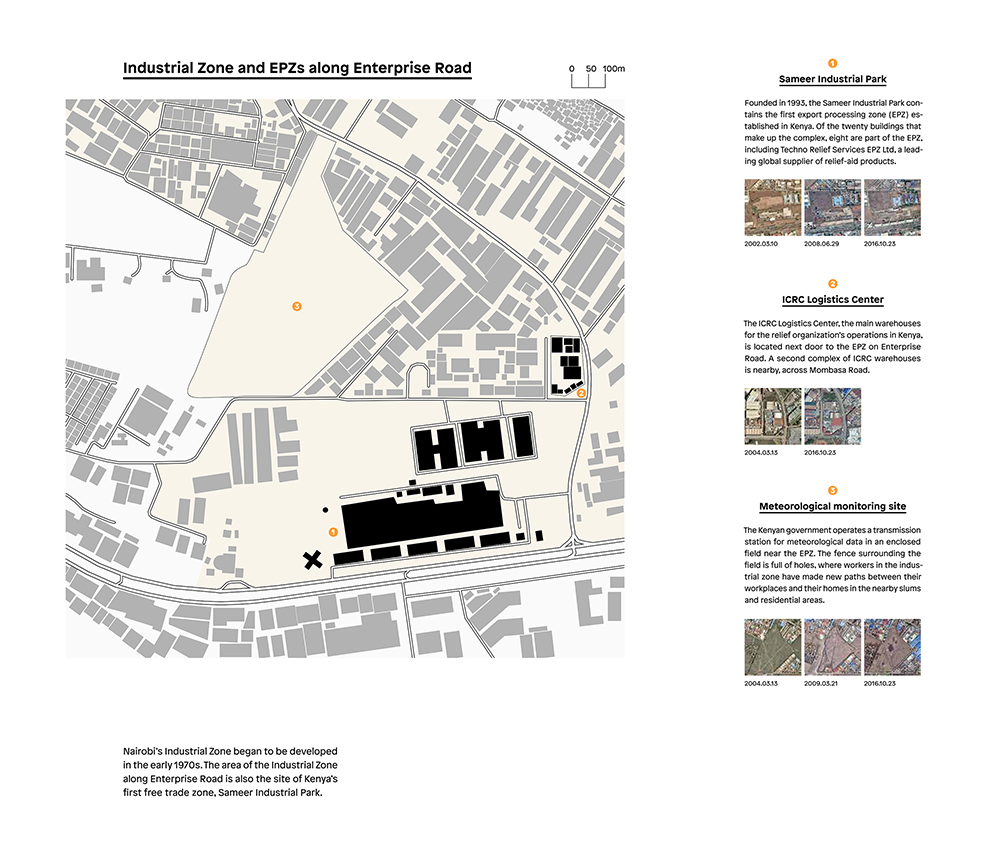

But the extraterritoriality of humanitarianism is not limited to the land parcels occupied by international diplomatic organizations. The growth of the Mukuru settlement in Nairobi, now one of the city’s largest, was driven in part by the Kenyan government’s development of an industrial zone, and later the tax-free Sameer Industrial Park EPZ, on the edge of the city, near the airport.

Mukuru’s earliest residents were workers who voluntarily resettled in areas adjacent to the zone to be closer to the factories and the possibilities of employment they offer. Perhaps ironically, the park currently houses the Kenyan warehouses of Médicins Sans Frontières, and its EPZ leases space to several companies that are international manufacturers and distributors of relief supplies, contracted by the UN and NGOs for their work in Kenya’s settlements and around the world.

Humanitarianism beyond the state

Lastly—and this perhaps represents the best possibility that we see for directing architectural practice—the research suggests a reconsideration of the spaces of humanitarianism as representing the possibility of a politics beyond the nation-state. Humanitarianism claims a moral purpose, in that it acts not in the interests of any parties, but for the good of humanity itself. In this sense, humanitarianism is sometimes seen as opposed to or transcending political life. But humanitarian operations and their effects on cities are perhaps opposed not to the political, but to the state; or, more precisely, to the spatial ordering of state territory through the institutions of private land ownership and national boundaries.

Humanitarian spaces might point toward new spatial and political formations: governance structures, property laws, and models of land tenure that respect the complex forms of ownership seen in refugee camps and other communities where no land titles exist, or where land has never been formally divided into parcels, or that lack a legal distinction between public and private space. The refugee camp is therefore not outside the realm of politics, but rather points toward a political community beyond the nation-state, and beyond property and territory, the spatial extensions of the state.

Seen in this light, humanitarian spaces, like camps and settlements, might not be outside the polis; rather they are emerging sites of another politics. The architecture of these humanitarian spaces would be designed not for a universal humanity reduced to its basic needs, but for the human of a political life yet to come.

Biographies

is a founding partner of Interval Projects, a design practice based in New York.

is a founding partner of Interval Projects, a design practice based in New York.

Explore

A conversation with Mark Willis

An interview with the former Deputy Commissioner for Development at NYC Housing Preservation and Development, who was instrumental in organizing Vacant Lots.

Interview: MASS Design Group

An interview with Michael Murphy of MASS Design Group.

Potable water and local power struggles in Honduras

Timothy Kohut reflects on alternative visions for community development in Tegucigalpa.