Everything old is new again

For Miriam Peterson and Nathan Rich, adaptive reuse projects offer uniquely exciting design challenges.

April 14, 2020

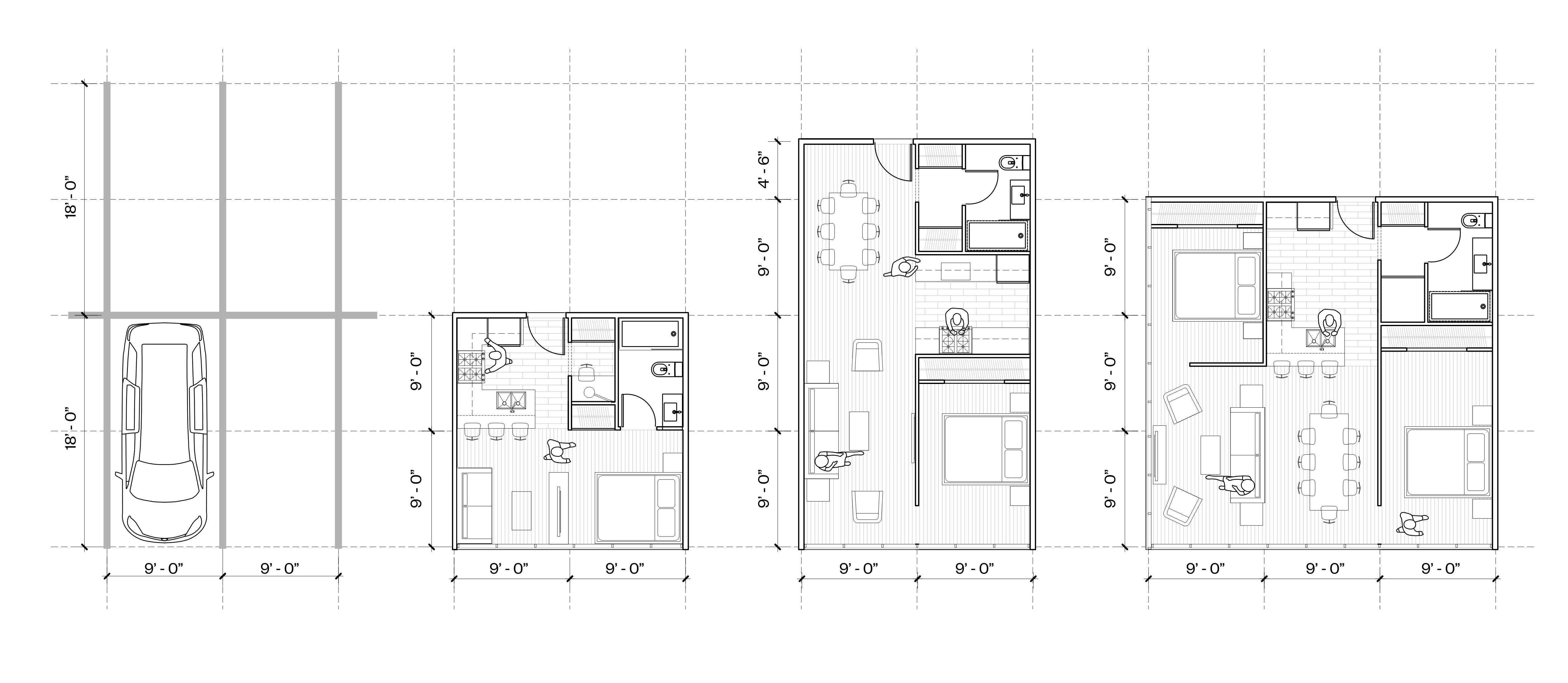

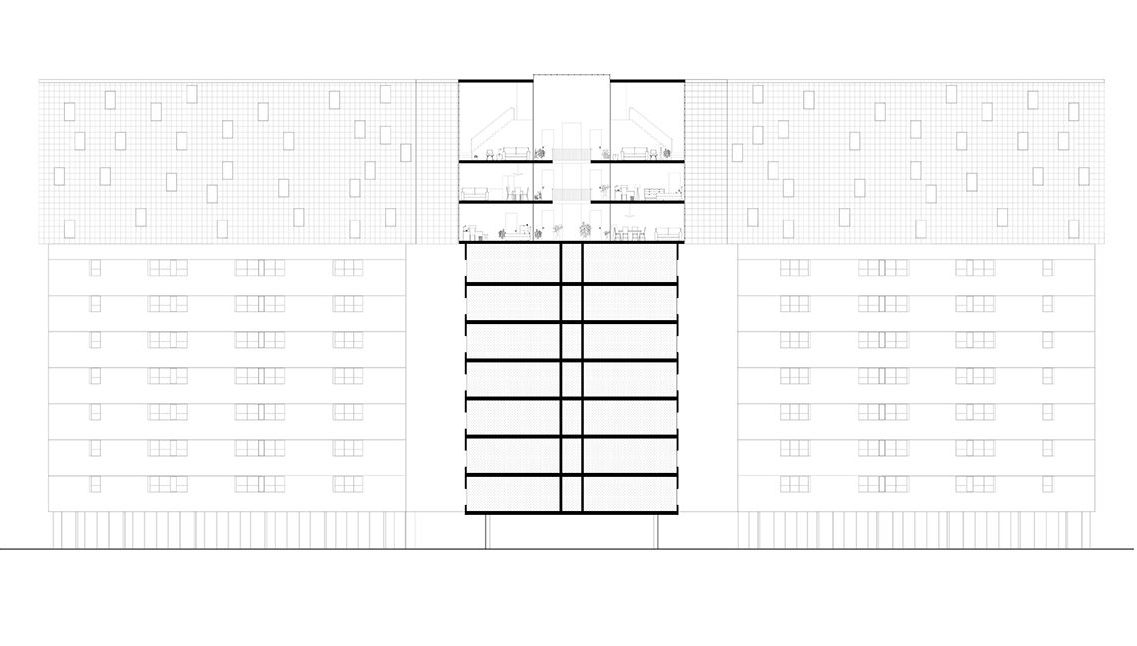

PRO's Roof by Roof study looked at the potential to add affordable housing to New York's public housing campuses while addressing the need for repairs and upgrades in existing buildings. Credit: Peterson Rich Office

By Sarah Wesseler

In New York, young architecture firms often get their start doing apartment renovations or storefront fit-outs, dreaming all the while of graduating to ground-up buildings. Peterson Rich Office (PRO) has followed a somewhat different trajectory. As their practice has grown, founders Miriam Peterson and Nathan Rich have found themselves taking on adaptive reuse projects across different scales and sectors—and getting increasingly excited about them. The constraints inherent in working with existing buildings—the need for deep engagement with issues of structure, history, and ecology, for instance—make for a particularly fascinating design challenge.

Several of PRO’s projects have explored potential changes to buildings owned by the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). Adaptive reuse wasn’t the initial focus of this work; instead, it started in 2014 with a study of the potential links between NYCHA’s controversial proposal to let developers lease space on public housing campuses and Mayor Bill de Blasio’s pledge to create 80,000 new affordable homes. Partnering with urban designer Sagi Golan, PRO used the area of a typical parking space as a starting point for design investigations and community engagement around the idea of building affordable apartments on NYCHA parking lots.

After the study won praise from The New York Times and other media outlets, PRO and Golan were invited to have further conversations with NYCHA staff. But these discussions made it clear that, while the agency found the study compelling, it had little bandwidth for anything except the massive backlog of repairs and upgrades that were urgently needed in its existing building stock.

The plan to lease NYCHA land had been devised as a partial solution to this problem, with the proceeds going toward repairs. But even in the best-case scenario, it would take time for these funds to work their way through the NYCHA system. In the meantime, tenants could be inconvenienced by construction near their homes while concerns about issues like water damage and mold remained unaddressed.

In 2018 PRO began a second NYCHA study, this time looking for ways to directly link new affordable housing development to existing building upgrades. Working with Silman structural engineers and Karakusevic Carson Architects, a London firm with extensive public housing experience, PRO explored the potential to create additional floors on top of NYCHA towers. This would allow the buildings’ common areas—cores, elevators, and potentially even cladding—to be improved as part of the same effort, so that “the residents of the host campus immediately and tangibly benefit from any construction that happens in their home,” Peterson said.

Peterson and Rich are now working on a third NYCHA project for the Regional Plan Association, which selected PRO as its inaugural Richard Kaplan Chair for Urban Design. The study is a kind of hybrid of the first two, seeking ways to create new affordable units in existing buildings while addressing campus-level challenges such as a lack of integration between individual structures and the surrounding streets. The proposal envisions extending buildings horizontally to redefine outdoor spaces and create new, open lobbies. The extensions will also include studios and one-bedroom apartments, which are missing from original NYCHA buildings but currently in high demand, particularly for seniors.

While PRO’s NYCHA projects have thus far been limited to provocations, the firm has broader ambitions. “Our goal is not just to propose studies, but to ultimately be able to do some real work on these buildings,” Rich said. But the time they’ve invested to date has been invaluable, the partners say. Spending years talking with tenants, city officials, and other stakeholders has greatly improved their understanding of New York City public housing, allowing them to tailor their designs much more precisely to residents’ needs.

The idea of generating designs through careful study of existing conditions has been central to PRO’s adaptive reuse work in a very different context: the contemporary art world. For the flagship space of Galerie Perrotin, the firm converted a nineteenth-century textile warehouse in Manhattan’s Lower East Side into a 25,000 square foot facility offering residences and a café as well as exhibition spaces.

In the project’s initial phases, Peterson and Rich collaborated with Silman to understand how the building had been originally designed. They found that it relied on a construction methodology common in the early 1900s, with hollow clay tile arches sandwiched between steel beams. More than a century later, the structural system was still robust, but didn’t lend itself to simple modification. The designers studied the existing beam and arch locations carefully to find opportunities to create penetrations without jeopardizing the structure’s integrity.

The structural arches also created an opportunity to develop a unique architectural identity for the gallery. In the finished building, the undulating ceiling conceals sprinkler heads, light track, structural hanging points, and indirect cove points—an efficient organizational strategy that also gives the galleries their distinctive appearance.

PRO's design for Galerie Perrotin took advantage of the building's existing structural system to create distinctive barrel-vaulted ceilings. Credit: Guillaume Ziccarelli

For a current project, PRO is converting an empty church into a cultural center for a client who hopes the facility will bring new life to a depopulated Detroit neighborhood. As with the NYCHA work, this effort has led PRO to have discussions with municipal officials—in this case, about making it easier to reuse other empty buildings throughout the city. “We’re thinking broadly about how a physical structure like this one can operate within a community in a very different way than its original purpose,” Peterson said. “What are the different ways that the city could, through law and policy, actually facilitate more conversions of churches to public and community uses? And what should the list of those [uses] be?”

For PRO, the process of working through layers of history, structure, form, and materiality on efforts like the church conversion is particularly fulfilling. “As the scale of the projects get bigger, the challenges become more and more interesting and exciting,” Rich said. “How can we study something that has this really strong existing presence in the city, and maybe a historic quality to it, and try to bring that into something new?”

Explore

A home of one’s own: Micro-lofts for single adults and small families

The micro-loft typology is designed to provide affordable housing for a growing and changing population in New York City.

Low Rise High Density

Notes from a 2013 exhibition about housing at the Center for Architecture.

Amanda Levete: A tale of two museums

British architect Amanda Levete explores recent cultural projects in Lisbon and London.