Building as BFF? Yes Please, Says Could Be Design

For the Chicago practice, creating playful, accessible architectural experiences is serious business.

August 29, 2023

In 2021, Could Be Design depicted a safe, happy gathering of people and buildings made possible by the COVID-19 vaccine. The image was created as part of a public health campaign promoting vaccination developed by the Chicago mayor's office and curated by the Design Museum of Chicago. Photo: Della Perrone

Could Be Design is a 2023 League Prize winner.

For Joseph Altshuler and Zack Morrison, founders of Chicago firm Could Be Design, taking architecture’s social potential seriously means not taking architecture too seriously. Their projects explore the “creaturely” possibilities of buildings and spaces, envisioning them as animate beings that can form personal bonds with humans—and vice versa. By helping people see architecture in new ways, the designers hope to offer a greater sense of agency in shaping the built environment.

The League’s Alicia Botero spoke with Altshuler and Morrison about their work.

*

Alicia Botero: When talking about your practice, you often start by explaining that you want people to view buildings as animate beings that have agency. Can you say more about this idea and how it came to be a central part of your work?

Zack Morrison: We’re constantly looking to convince people that the built environment is alive and that it is a kind of non-human companion with which we can build relationships.

We find a more traditional understanding of the relationship between humans and architecture too one-directional and utilitarian: Like, architecture is here to serve our needs, to keep us dry, to keep us warm and sheltered. Which is definitely true and really important. But we’re interested in expanding this mindset and showing that architecture can be so much more: That it can also be part of a reciprocal or even mutual relationship between biotic beings and abiotic beings; that we can form friendships [with architecture].

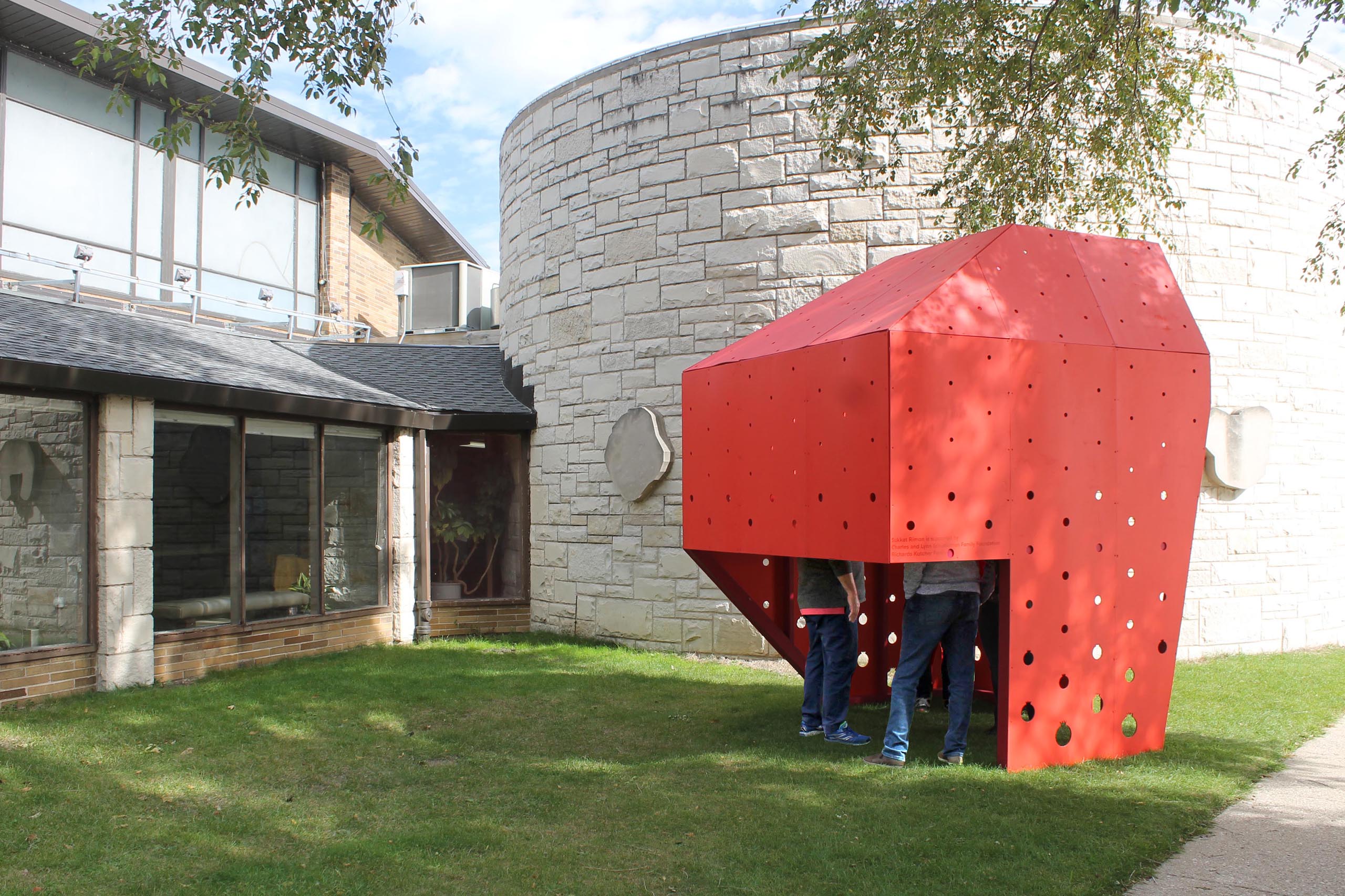

With its Animate Arcade installation, Could Be Design created what it has described as a “family of independent but related architectural ‘creatures'” for the public spaces of the Siebel Center for Design at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Image credits: Brian Griffin

Botero: I’m curious how this concept developed in relation to your practice. Did you have the idea and begin the practice to materialize it, or has the idea emerged as a result of practicing together?

Joseph Altshuler: It wasn’t a linear process, but I would say that this idea led to our desire to start the practice. We both identified this mutual interest in a way of looking at the world, and that’s largely what convinced us to start a practice to explore it.

We were grad students together at Rice University, which is also where we first met. We lived across the street from each other in Houston, Texas.

Morrison: Two Chicagoans who had to go to Texas to meet!

Altshuler: At that time, there was a broad interest in the political agency of architecture at Rice, which I think our interest is a weird subset of. But there was a resistance on the part of some of our peers and faculty to embrace architecture’s more narrative, and sometimes even comical and goofy, side.

And there’s perhaps a certain relationship to Postmodernism, although this isn’t central to our practice: of not being afraid to explore the role of visual resemblance and narrative in architecture. Our teachers suggested that what architecture does is more important than what it looks like. We’re more interested in exploring how what architecture looks like is what it does—that aesthetics, and sometimes even visual resemblance, has its own agency in the world. For example, if architecture looks like an animate creature, that might change the way we behave around it, and with each other. We didn’t find a lot of camaraderie around that idea in school, so it drew us to each other.

The firm's 2022 installation Gary-goyles added a series of brightly colored anthropomorphic figures to crosswalks in Gary, Indiana. Image credit: Brian Griffin

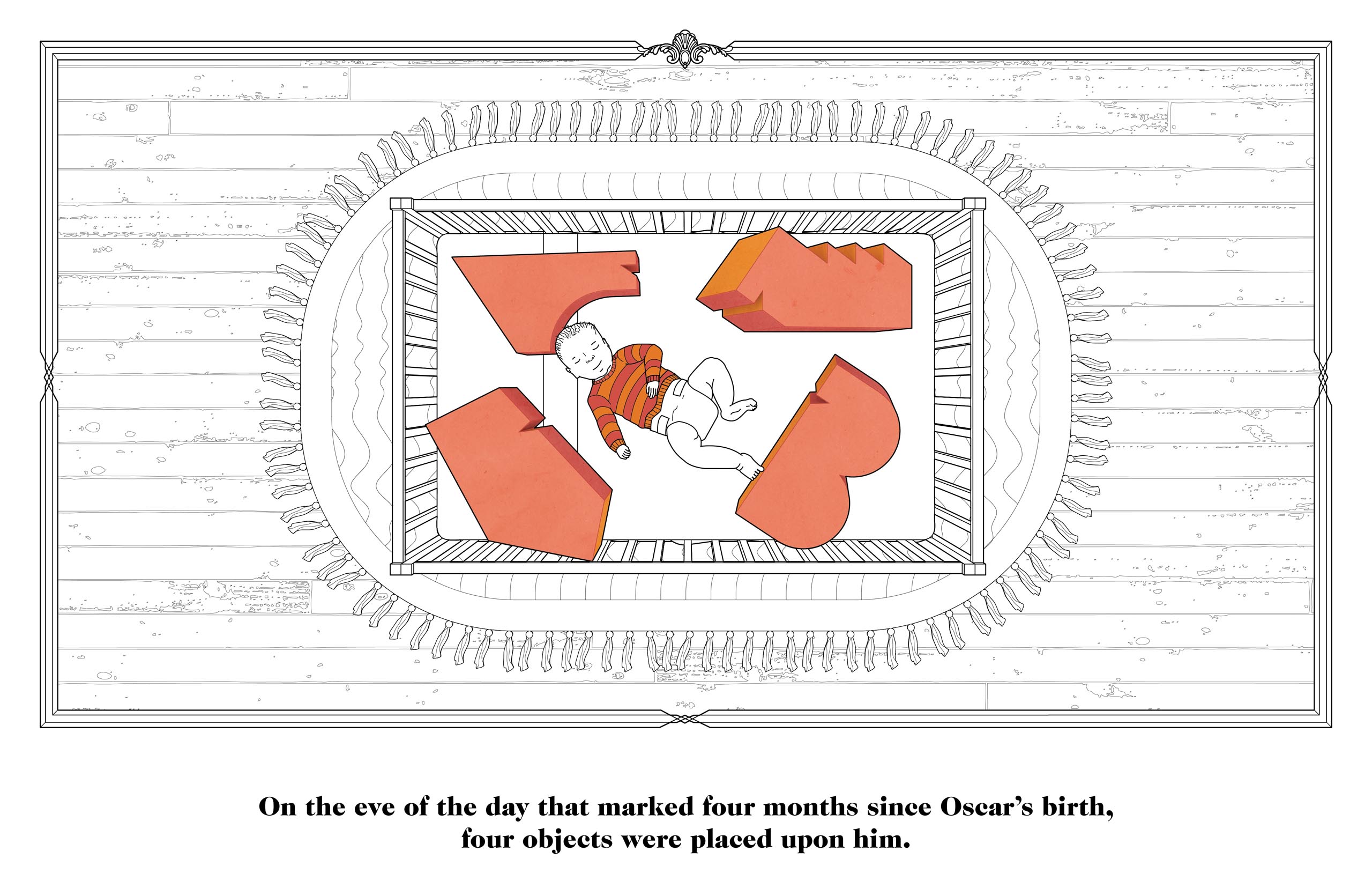

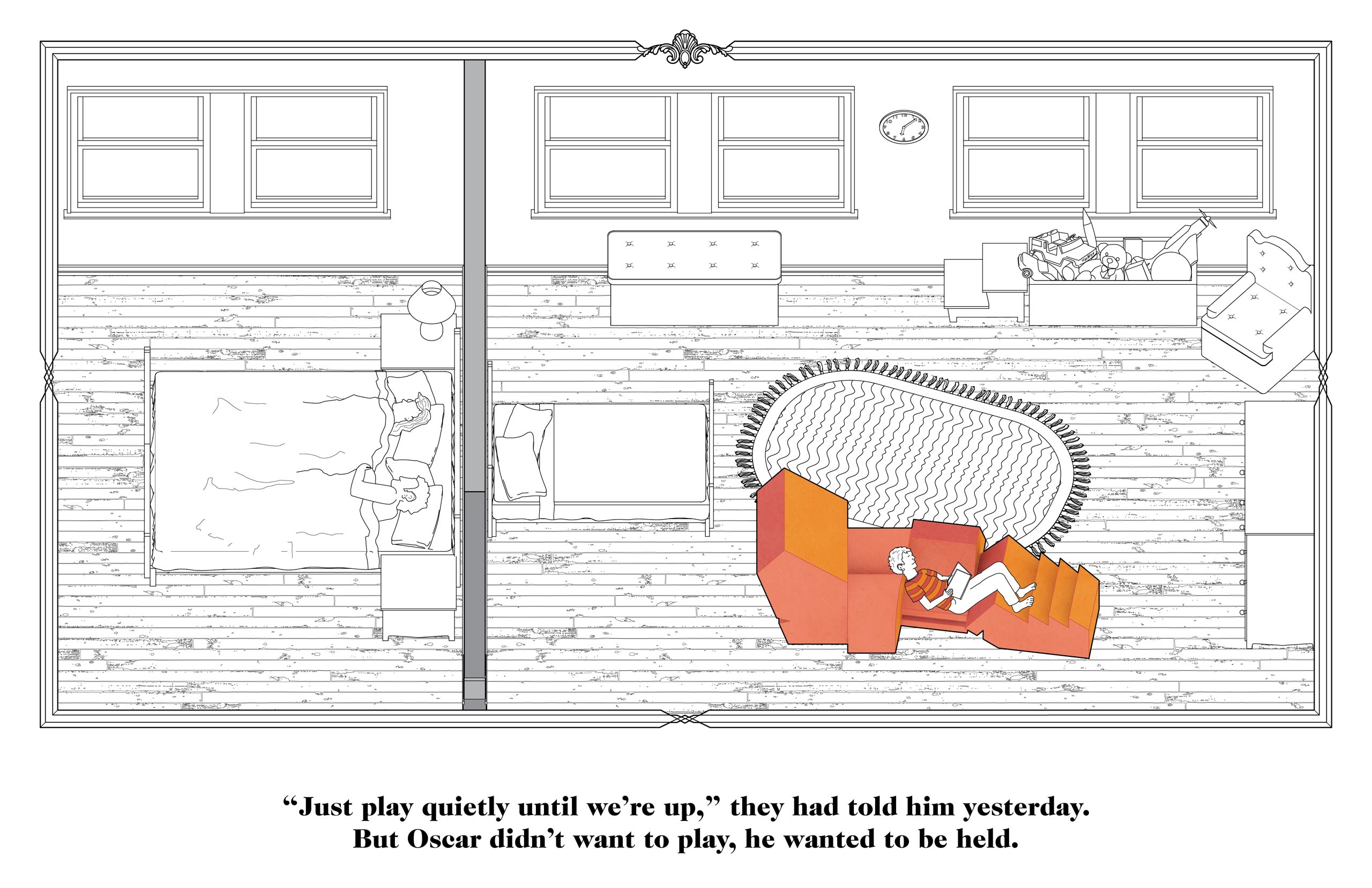

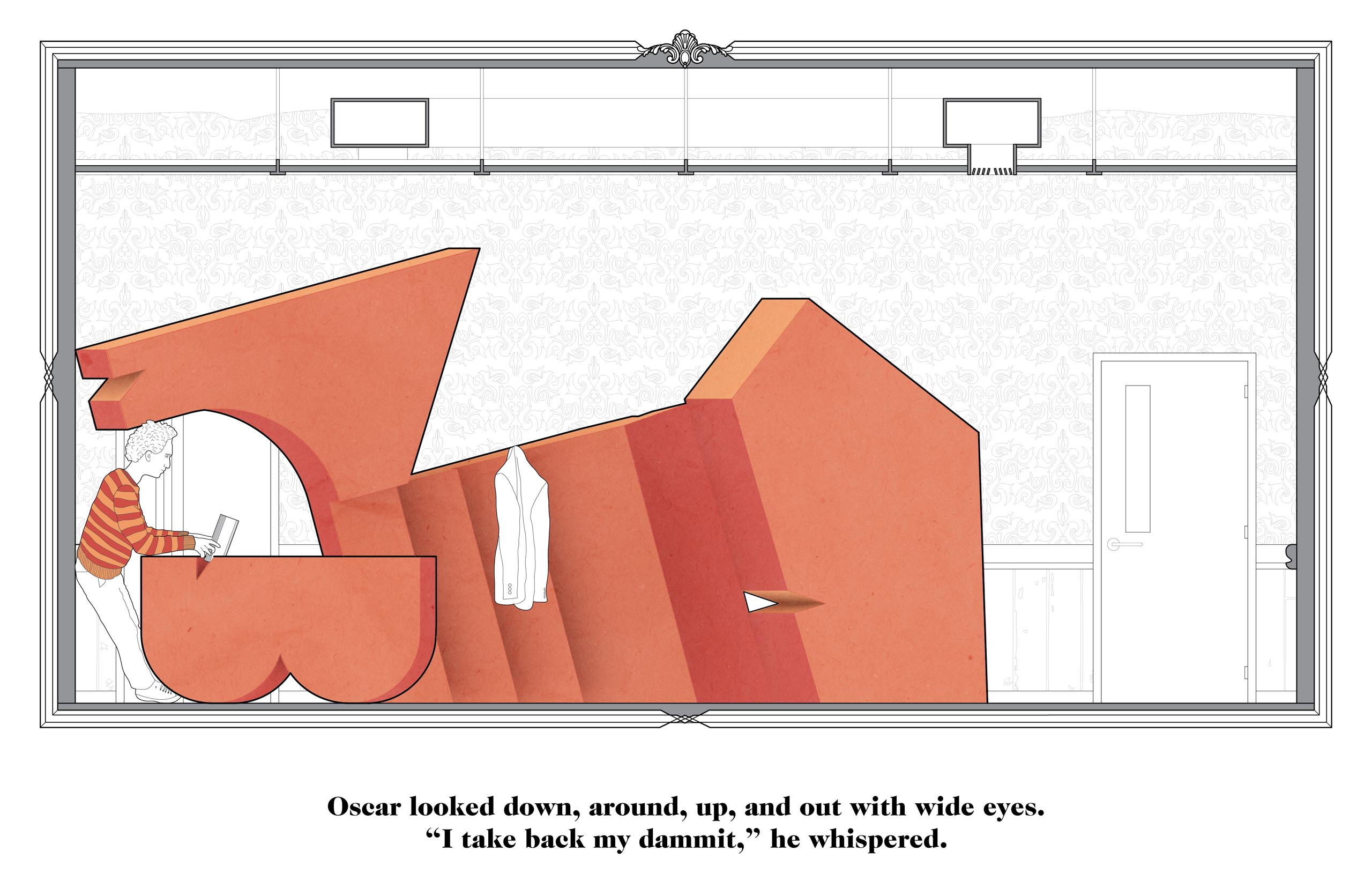

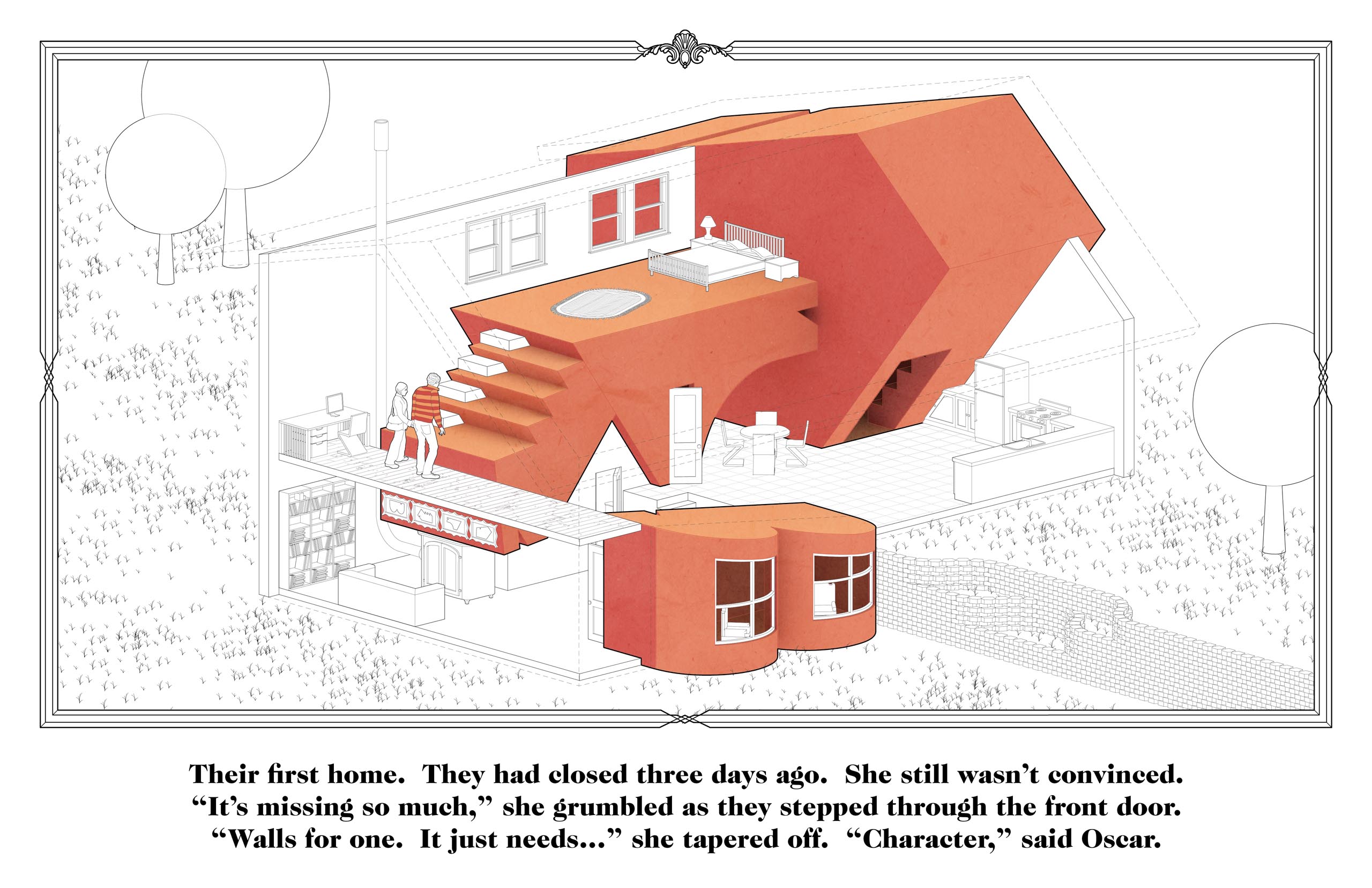

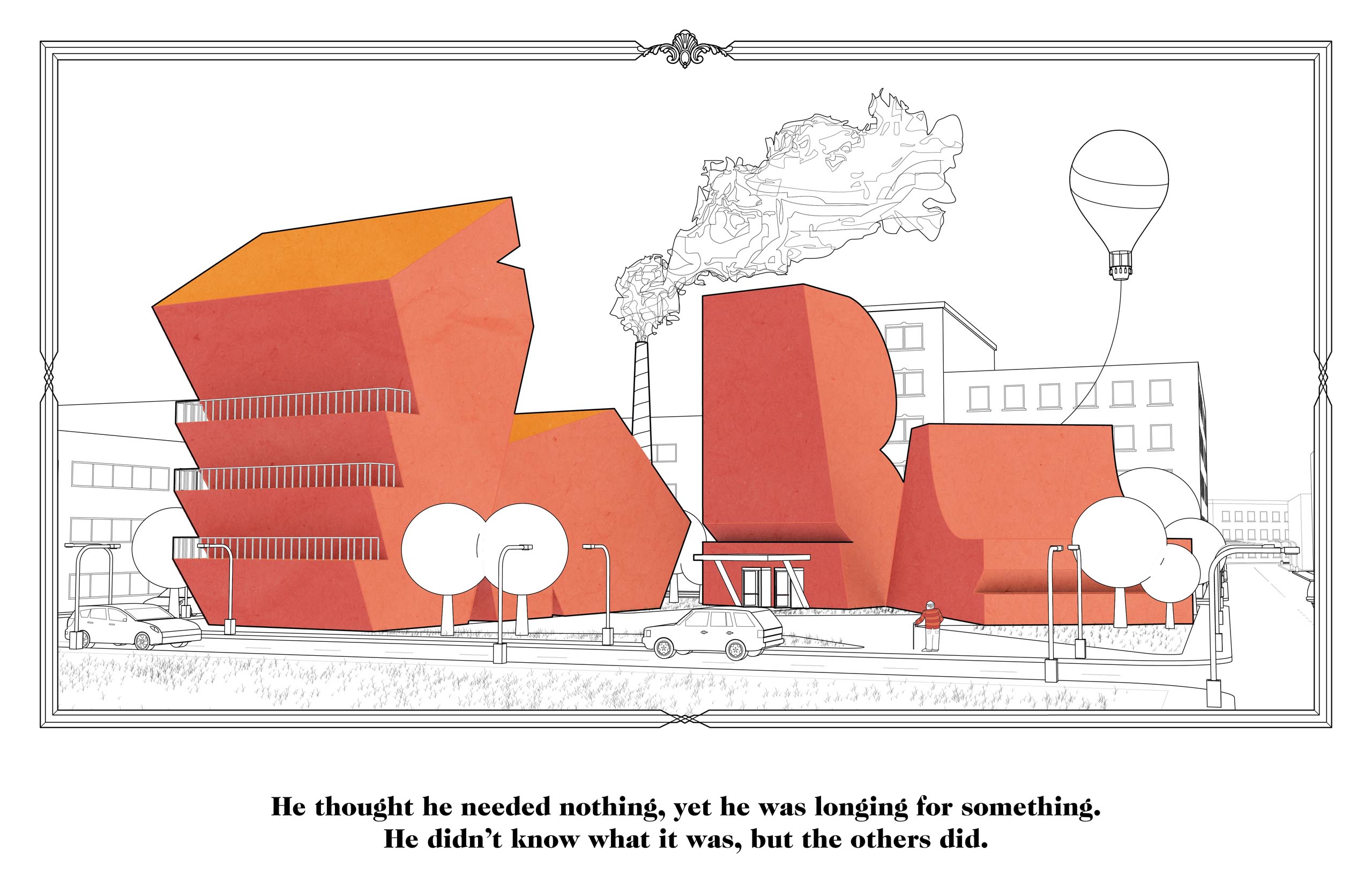

Before we officially started our practice, we entered a competition that asked architects to write a fairy tale, run by an organization called Blank Space. It was very appealing to us at the time because we were trying to make a case for what narrative can do for architecture.

We essentially wrote an illustrated children’s book about a human character named Oscar who has a lifelong, intimate, important relationship with architecture, and specifically these kinds of fairy-tale architectural creatures he’s gifted on his four-month birthday that follow him and grow with him throughout his life. But they grow at a much more exponential rate than the human body: They start out as toy-scale, then very quickly become furniture- and building-scale as he grows up. That story became a kind of manifesto, or a rehearsal, for our practice.

Botero: Can you walk me through some of the ways you think of building companionship with architecture through your projects? I’m curious about the McCormick AfterParti and the 5K race project, for example.

Altshuler: Yeah, those are good examples. In the case of the McCormick AfterParti, that project is an architectural installation within the McCormick House, which is one of only three single-family houses Mies van der Rohe designed in the United States. The building has been converted into a museum gallery, and when we were invited to create an interior architecture within it, we were interested in reenacting some of the domesticity and intimacy that was diminished during that conversion.

Morrison: We think the identity of the McCormick House is in a weird in-between state—between single-family house and a museum gallery. There are some traces of how it operated as a domestic space, but not many. So the reenactment was about using curtains to retrace the home’s original walls to reinforce how the domestic layout used to work, as a way to open up a conversation about the home’s renovation, evolution, and preservation to a much broader audience.

The McCormick AfterParti installation used curtains to recreate walls from a Mies van der Rohe–designed home in Chicago that were removed when the structure was turned into a museum. Image credits: Steven Koch

Altshuler: The reenactment wasn’t about replicating or restoring what the interior of the historic home looked like; it was about using aesthetics married with organizational strategies to reenact how it operated and behaved. The project sometimes exaggerates the behaviors we imagined might have taken place, sometimes on a comical level: Like, we reenacted the galley kitchen fixtures and filled them with candy that visitors could take.

It’s a kind of exaggerated way of approaching preservation, thinking about how the act of preservation can be theatrical and interactive: something that you can touch and experience, instead of making a very precious replication of a past image, cordoned off by a “do not touch” sign. We wanted to create a space that looks totally different than it would have in the past, but that starts to tease out behaviors or activities that might have taken place there.

Morrison: Another example is the puppet theater stage we inserted between what used to be the playroom and the living room. The idea was to literally poke a hole in the wall where child’s play and adult entertaining might have happened, teasing out those behaviors and questioning them in a slightly cheeky way.

The 5K race project was also about exaggerating behaviors and interactions around existing activities in the world, specifically architecture tours and athletic race competitions. By mashing up an architectural tour and a 5K route in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, the project aimed to invite existing audiences to experience a particular neighborhood in a totally different way.

Altshuler: It was a very circuitous and nonintuitive route because we were trying to point people’s attention to as much architectural splendor as possible . . . which maybe came at the cost of causing of couple people to get lost. But that’s okay, because then they made other discoveries in the process. So no one broke their personal record, but we created a space where athletes and biennial tourists and neighborhood enthusiasts could intersect in a way that they wouldn’t otherwise.

As part of the 2019 Chicago Architectural Biennal, Could Be Design developed the Bronzeville Bustle 5K, an architecture-themed running tour through the Bronzeville and Washington Park neighborhoods. At the finish line, participants were invited to create models of buildings seen along the route. Image credits: left, Could Be Design; right, Black Chicago Runners

I think these programming experiments are always about intersectionality of different audiences, and they come with a broader ambition of expanding and diversifying the audiences for architecture.

Chicago has this amazing architectural legacy, and there are multiple organizations dedicated to celebrating that, but we think those institutions still have a kind of limited definition of architecture. We’re interested in how the celebration of architecture in Chicago can be expanded so that it isn’t always oriented around Mies van der Rohe buildings and other very well-known pieces of the canon. For example, you could create a 5K in every neighborhood that celebrates architecture and creates a heightened sense of love and companionship around it.

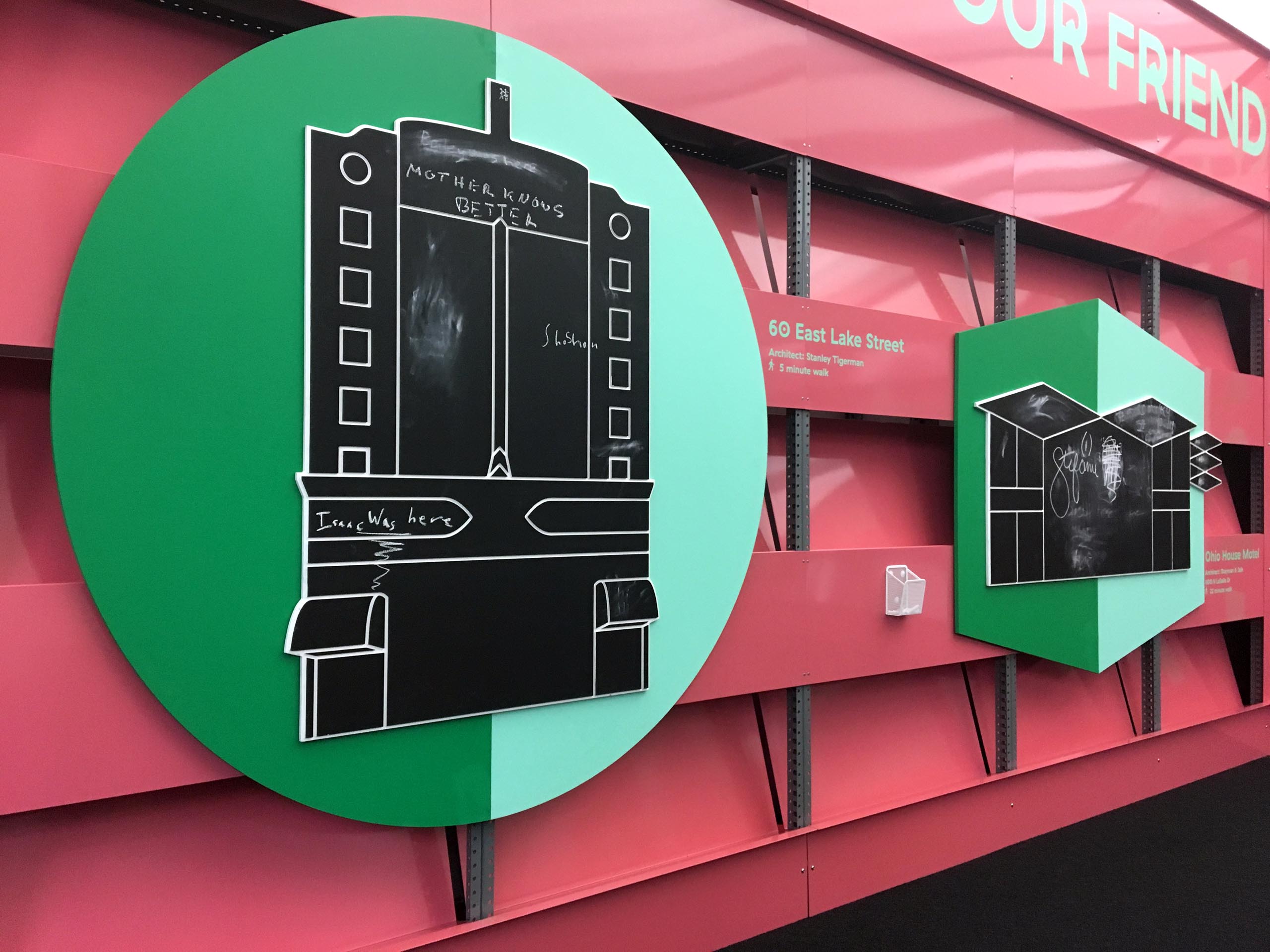

Botero: Yeah, I’m also remembering the project where people can intervene in images of historic sites in Chicago by drawing on them with chalk. Could you talk a bit more about your approach to expanding the audience for architecture and making it more accessible?

Altshuler: I think we find agency in creating multisensorial opportunities for action to occur in and around architecture, because we have a hunch that when people are engaging their multiple senses it’s a really powerful way of forming companionship. That’s a way that people can both form a relationship with architecture and form memories that are connected to it—and, dare we say, even have a better understanding of their own agency in an evolving story of the built environment. No architecture is fixed in place.

So projects like the one you mentioned, which we call Architectural Portraits, invite people to draw modifications on these seemingly fixed-in-stone landmarks in the city, which creates a kind of back and forth: a mutual process of co-agency in determining what the future of the built environment looks like.

Botero: Can you talk about the relationship between accessibility and different kinds of formal decisions in your work? How do your decisions about color, shape, et cetera, relate to this desire to draw in people from outside the discipline?

Altshuler: Colors usually come out of some dialogue between our own affinity for what we like to call “juicy” colors and the existing textures and layers in the world through which we find a project. We’re never operating on a blank slate. There’s always a rich context to respond to.

Morrison: We think of bright color as a signifier of activity: It can catch your eye from down the street, or you can open a door and there’s this totally new world. We use color to contrast the typical materiality of the world. There’s a lot of brick and wood and concrete in the world.

Could Be Design's Pomegranate Sukkah was installed at a Chicago synagogue in 2019. Image courtesy Could Be Design

Altshuler: Which speaks to this broader ambition for exaggeration. We’re interested in how we can exaggerate things to make people more aware of them, and hopefully participate in them more at the same time.

There’s this false dichotomy between synthetic, artificial colors and natural materials that I think is a little silly. We’re interested in embracing this idea of the synthetic everywhere. All architecture, regardless of whether or not it’s made out of a natural-looking material, is a kind of artificial or synthetic construct of imagination. There is no natural architecture. So for us, exaggeration is yet another way to remind people of their own agency and their own imagination in any space in the world.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

Revisiting Postmodernism

A digital archive of talks held at The Architectural League by leading theorists and practitioners of 1980s postmodernism.

Taking humor seriously

Mustafa Faruki believes that architecture should reflect the full range of human emotions.

All the Queens Houses

All the Queens Houses features photographs of 273 houses in Queens by Rafael Herrin-Ferri.